полная версия

полная версияBuffalo Land

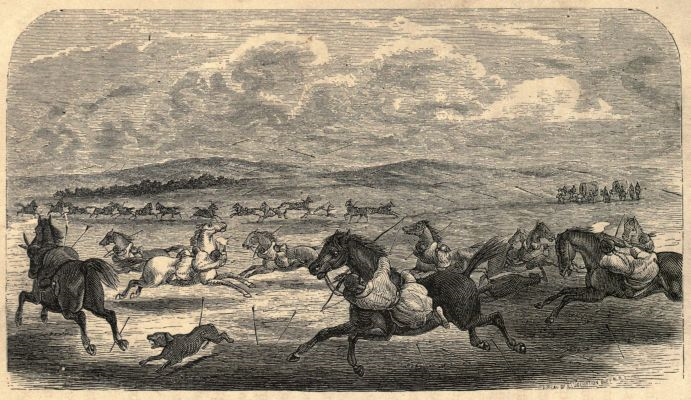

White Wolf stated that he had been out after Pawnees; he could not find them, and so "Indian felt heap bad!" Just at this instant a loud, quick cry came from his knot of warriors, who were now manifesting the wildest excitement, lashing up their ponies, stringing their bows, and making other preparations as if for a fight. Without a word, the chief turned and ran for dear life toward his band, while the Professor and our guide wheeled and ran for dear life toward us. Seldom has the man of science made such progress as did the respected leader of our expedition then. The guide called, "Cover us with your guns!"—a command which we immediately proceeded to obey, evidently to the intense alarm of the Professor, for so completely were they covered, that I doubt if either would have escaped, had we been called upon to fire.

Our first thought had been a suspicion of treachery, but we now saw that the Cheyennes had faced toward the hills, and, following their gaze, we beheld coming down their trail, and upon the tracks of our wagon, another band of mounted Indians. It soon became clear to us that the Pawnees, the Wolf's failure to find whom had made that noble red man feel "heap bad," were coming to find him. We counted them riding along, twenty-five in all—inferior in numbers, it was true, but superior to the Cheyennes in respect to their arms, so that, upon the whole, the two forces now about to come together were not unevenly matched. The Pawnees live beyond the Platte, and for years have been friendly to the whites, even serving in the wars against the other tribes on several occasions.

What a stir there was in the late peaceful valley! The buffalo that were lately feeding along the brow of the plateau had all fled, and here right before us were sixty-five native Americans, bent upon killing each other off, directly under the eyes of their traditional destroyer, the white man. The Professor said it forcibly suggested to his mind some of the fearful gladiatorial tragedies of antiquity. Sachem responded that he wasn't much of a Roman himself, but he could say that in this show he was very glad we occupied the box-seat, the safest place anywhere around there; and we all decided that it must be a face-to-face fight, in which neither party dare run, as that would be disorganization and destruction.

It was strange to see these wild Ishmaelites of the plains warring against each other. Over the wide territory, broad enough for thousands of such pitiful tribes, they had sought out each other for a bloody duel, like two gangs of pirates in combat on mid-ocean; and, like them, if either or both were killed, the world would be all the better for it. It was clearly what would be called, on Wall street, a "brokers' war," in which, when the operators are preying on each other, outsiders are safe.

While we were looking, a wild, disagreeable shout came up from the twenty-five Pawnees, as they charged down into the valley, which was promptly responded to by fierce yells from the forty Cheyennes.

"Let it be our task to bury the dead," said the Professor, looking toward the wagon in which rested his geological spade. "It is extremely problematical whether any of these red men will go out of the valley alive."

And thus another wonderful change had come over the spirit of our dream. From being a scientific and sporting expedition, we had been suddenly metamorphosed into a gang of sextons, who, in a valley among the buffaloes, were witnessing an Indian battle, and waiting to bury the slain.

As the Pawnees came down at full gallop, the Cheyennes lashed up their ponies to meet them. Then came the crack of pistols, and a perfect storm of arrows passed and crossed each other in mid-air. As the combatants met, we could see them poking lances at each other's ribs for an instant, and then each side retreated to its starting point. Charge first was ended. We gazed over the battle-field to count the dead, but to our surprise none appeared.

BATTLE BETWEEN CHEYENNES AND PAWNEES.

A few minutes were spent by both parties in a general overhauling of their equipments, and then another charge was made. They rode across each other's fronts and around in circles, firing their arrows and yelling like demons, and occasionally, when two combatants accidentally got close together, prodding away with lances. The oddest part of the whole terrible tragedy to us was that the charges looked, when closely approaching each other, as if they were being made by two riderless bands of wild ponies.

The Indians would lie along that side of their horses which was turned away from the enemy, and fire their pistols and shoot their arrows from under the animals' necks, thus leaving exposed in the saddle only that portion of the savage anatomy which was capable of receiving the largest number of arrows with results the least possibly dangerous. I noticed one fat old fellow whose pony carried him out of battle with two arrows sticking in the portion thus unprotected, like pins in a cushion. He still kept up his yelling, but it struck me that there was a touch of anguish in the tone, and I felt confident that he would not sit down and tell his children of the battle for some time to come.

We saw one exhibition of horsemanship which especially excited our admiration. An arrow struck a Cheyenne on the forehead, glancing off, but stunning him so with its iron point, that, after swaying in the saddle for an instant, he fell to the earth. Another of the tribe, who was following at full speed, leaned toward the ground, and checking his pony but slightly, seized the prostrate warrior by the waistband, and, flinging him across his horse in front of the saddle, rode on out of the battle.

For several hours—indeed until the sun was low in the heavens and the shadows crept into the valley—this terrible fray continued, the charging, shouting, and firing being kept up until both combatants had worked down the river so far that we could no longer see them.

It was approaching the dusk of evening when White Wolf and his band rode back. We counted them and found the original forty still alive. The chief assured us they had killed "heap Pawnees," whereupon some of us sallied forth to visit the battle-field. Three dead ponies lay there, and with a disagreeable sensation we looked around, expecting to discover the mangled riders near by. Not one was visible, however, nor even the least sign of their blood. The grass was not sodden with gore, nor did a single rigid arm or aboriginal toe stick up in the gathering gloom. Neither the wolves or buzzards gathered over the field, and slowly the conviction dawned upon us that Indian battles, like some other things, are not always what they seem.

As we turned again toward camp, the Professor, dragging his spade after him, suggested that, in accordance with the reputed habits of these savages, the Pawnees had perhaps carried off their dead. But at the instant, only a short distance down the river, the camp-fire of that miserable and all but annihilated band glimmered forth. It was decidedly too bold and cheerful for the use of twenty-five ghosts, and we knew then that White Wolf had lied.

That valorous chieftain we found limping around outside our wagons, with a lance-cut in one of his legs, while several of his warriors had arrow-wounds, and one a pistol-shot, none of the injuries, however, being dangerous. The Pawnees probably suffered with equal severity; and this was the sum total of the day's frightful carnage—the entire result of all the fierce display that we had witnessed.

Not long afterward, in front of a Government fort, and in plain sight of the garrison, a battle occurred between two large parties of rival tribes, about equal in numbers. Back and forth, amid furious cries and clouds of arrows, the hostile savages charged. Noon saw the affair commenced, and sunset scarcely beheld its ending. The Government report states, if my memory serves me correctly, that one Indian and two horses were killed; and a shade of doubt still exists among the witnesses whether that one unlucky warrior did not break his neck by the fall of his pony!

These savages fight on horseback, and are neither bold nor successful, except when the attacking party is overwhelming in numbers, and then the affair becomes a massacre. All this knowledge came to us afterward, but our first introduction to it was a surprise. Kind-hearted man though he was, I think the resultless ending of the battle disconcerted even the Professor. Having nerved one's self to expect horrors, it is natural to seek, on the gloomy mirror of fate, some rays of glimmering light which can be turned to advantage. I think the Professor's rays, had the contest proved as sanguinary as we first anticipated, would have found their focus in some stout cask containing a nicely-pickled Pawnee or Cheyenne en route to a distant dissecting table. It would have been rather a novel way, I have always thought, of sending the untutored savage to college.

We made a requisition upon our medicine-chest, and dressed the wounds of the suffering warriors. White Wolf stripped to the waist, and, exposing his broad, muscular form, exhibited thirty-six scars, where, in different battles, lances and arrows had struck him. It struck us all as a rather remarkable circumstance, though we prudently refrained from commenting upon it just then, that nearly all these scars were on his back.

The chief expressed great friendship for us, and I really believe he felt it. Sachem's stout form was especially the object of his admiration. Between these two worthies a very cordial regard seemed to be springing up, until White Wolf unluckily offered him an Indian bride and a hundred buffalo robes, if he would go with the band to its wigwams on the Arkansas—a proposition which disgusted our alderman beyond measure. Savages, sooner or later, generally scalp white sons-in-law, and it would be "heap good" for the Cheyenne to have such an opportunity always handy. Sachem declined the honor with all the dignity he could command, and carefully avoided "the match-making old heathen," as he termed him, for the remainder of the evening.

We kept early hours that night. Guard was doubled, to prevent any possible treachery, and a sleepy party laid down to rest. The Cheyennes went into camp a few hundred yards up the creek, a barely perceptible light, looking from our tents like a fire-fly, marking the spot.

When a "cold camp" is discovered on the plains, the experienced frontiersman can always determine at once whether white men or Indians made it, by the size of the ash-heap. The former, even when trying to make their fire a small one, will consume in one evening as much fuel as would last the red man a half-moon. The latter, putting together two or three buffalo chips, or as many twigs, will huddle over them when ignited, and extract warmth and heat enough for cooking from a flame that could scarcely be seen twenty yards.

The two opposing parties, which were now resting only a mile or so apart, had each tested the other's metal, and, as the sequel proved, found them foemen worthy of their steal. From the unconcealed fires in their respective camps, we concluded that neither side had any intention of attacking, or fear of being attacked.

It was early in the dawn of the next morning when we were startled from our slumbers by a terrific cry from Shamus, which brought all of us to our tent-doors, with rifles in hand ready to do battle, in the shortest possible time. Looking out, we beheld our cook standing near the first preparations of breakfast, and gazing with astonished eyes toward the darkness under the trees, among which we heard, or at least imagined we heard, the stealthy steps of moccasined feet. In answer to our interrogatories, Shamus stated that just as he was putting the meat in the pan, he saw the light of the fire reflected, for an instant, on a painted face peering out at him from behind a tree. "Faith, but I shaved the lad's head wid the skillet!" said Dobeen, and sure enough we found that article of culinary equipment lying at the foot of the suspected cottonwood, badly bent from contact with something, but whether that something was the bark or a painted skull is known only to that skulking Cheyenne.

We waited until broad daylight, but no further disturbance occurred, and what was strangest of all, the valley both above and below us seemed entirely destitute of either Pawnee or Cheyenne. A reconnoissance, which was made by the Professor, Mr. Colon, and our guide, developed the fact that not being able to steal any thing else, the savages had executed the difficult military maneuver of stealing away. Just before daybreak, the Pawnees had gone due north, and the Cheyennes, about the same time, due south. As White Wolf had expressed a cold-blooded intention of exterminating the remnant of his foes in the morning, the pitying stars may have taken the matter in hand and misled him; and if so, how disappointed that blood-thirsty band must have been when their path brought them into their own village, instead of the Pawnee camp! In confirmation of this astrological suggestion, I may say that while in Topeka I saw "stars," on several occasions, leading Indians in the opposite direction from that in which they wished to go.

In due time our party sat down to another plentiful breakfast, which was eaten with all the more relish because we had all that little world to ourselves again. Discussing Dobeen's apparition, we finally came to the unanimous conclusion that it was some Indian who, while his brothers stole away, had straggled behind, to pick up a keepsake. I think that hideous face among the trees never entirely ceased to haunt the chamber of Dobeen's memory. He shied as badly as did Muggs' mule, when in strange timber, and was ever afterward a warm advocate for pitching camp on the open prairie.

In justice to White Wolf, it should be stated that we afterward learned that while charging in such a mistaken direction after Pawnees that morning, he met two men from Hays City, out after buffalo meat. Finding that they were from the village which had been kind to him, he loaded their wagons with fat quarters, instead of filling their bodies with arrows, as they had first expected, and sent them home rejoicing.

CHAPTER XIX

STALKING THE BISON—BUFFALO AS OXEN—EXPENSIVE POWER—A BUFFALO AT A LUNATIC ASYLUM—THE GATEWAY TO THE HERDS—INFERNAL GRAPE-SHOT—NATURE'S BOMB-SHELLS—CRAWLING BEDOUINS—"THAR THEY HUMP"—THE SLAUGHTER BEGUN—AN INEFFECTUAL CHARGE—"KETCHING THE CRITTER"—RETURN TO CAMP—CALVES' HEAD ON THE STOMACH—AN UNPLEASANT EPISODE—WOLF BAITING, AND HOW IT IS DONE.

Breakfast over, the day's work was planned out. We were desirous of loading one of our wagons with game, and sending it back to Hays, from whence the meat could be forwarded by express to distant friends, and serve as tidings from camp, of "all's well." The other wagon we decided to keep with us. Horseback hunting, although fine sport, evidently would not, in our hands, prove sufficiently expeditious in procuring meat. Our guide adduced another argument as follows: "Yer see, gents, if yer want ter ship meat by rail, it won't do ter run it eight or ten miles, like a fox, and git it all heated up. Ther jints must be cool, or they'll spile." Stalking the bison was to be our day's sport, therefore, and we were speedily off, taking only the two wagons, the riding animals being all left in camp. Shamus prepared a lunch for us, as we did not expect to return for dinner before dusk.

Following the same route as the day before, we soon ascended the Saline "breaks," and emerged on the plains above. Looking to us as if they had not changed position for twenty-four hours, the buffalo herds still covered the face of the country, busy as ever in their constant occupation of feeding. For animals which perform no labor, they have an egregious appetite, eating as if they were Nature's lawn-gardeners, and were under contract with her to keep the grass shaved.

What an immense aggregate of animal power was running to waste before us. Those huge shoulders, to which the whole body seemed simply a base, were just the things for neck-yokes. Others, indeed, had thought the same before us, and tried to utilize these wild oxen. A gentleman at Salina, Kansas, obtained two buffalo calves, and trained them carefully to the yoke. They pulled admirably, but their very strength proved a temptation to them. A pasture-fence was no obstacle in the way of their sweet will. Not that they went over it, but they simply walked through it, boards being crushed as readily as a willow thicket. In summer they took the shortest road to water, regardless of intervening obstructions, and they thought nothing of flinging themselves over a perpendicular bank, wagon and all. After carefully calculating the result of his experiment at the end of the first year, the owner decided that, although he undoubtedly had a large amount of power on hand, he could obtain a similar quantity, at less expense, by buying a couple of steam-engines.

A few months previous to our trip, a contractor on the Kansas Pacific Railroad determined to domesticate a young bison bull, and accordingly took it to his home at Cincinnati. Proving a cross customer, he presented it to the Longview Lunatic Asylum, near that city, but there was no inmate insane enough to occupy the yard simultaneously with Taurus for any length of time. The first day he charged among the lunatics in a reckless manner, eliciting surprising activity of crazy legs. If exercise for their minds was what the poor creatures needed, they certainly obtained it, by calculating when and where to dodge.

Without loss of time, we set about finding a gateway into the herds. Looking at the surface before us, it appeared a level, unbroken plain, quite to the verge where it rolled up against the distant horizon. One would have maintained that even a ditch, if there, might be traced in its meanderings across the smooth brown floor. Yet deep ravines, miles in length, wound in and out among the herds, though to us entirely invisible. A short search discovered one of these, which promised to answer our purpose, and to lead to a spot where a large number of cows and calves were feeding. Fortunately the wind was north, so that we could creep into its teeth without sending to the timid mothers any tell-tale taint.

The wagons were stopped, and we got out, and descending into the hollow, moved forward. The walls on either side seemed disagreeably close. All around us was animal life, a small portion of which would have been sufficient, if so disposed, to make the concealed path which we were traversing a veritable "last ditch" to us. As we entered the ravine, some cayotes slunk out of it ahead of us, and one large gray wolf, with long gallop, disappeared over the banks. The temptation to fire at them was very strong, but prudence and the guide forbade.

We picked up some very fine specimens of "infernal grape," in the form of nearly round balls of iron pyrites. They lay upon the surface like canister-shot upon a battle-field. It seemed as if during the early period, when Mother Earth began to cool off a little, her fiery heart still palpitated so violently under her thin bodice, that beads of the molten life within, like drops of perspiration, had forced their way through, and, in cooling, had retained their bubble-like form. We could have picked up a half-bushel of them which would have made very fair aliment for cannon. The dogs of war could have spit them out as spitefully and fatally against human hearts as if the morsels had been prepared by human hands. From such well-molded shot, of no mortal make, Milton might have obtained his charges for those first cannon which the traitor-angel invented and employed against the embattled hosts of heaven. Shamus, when he afterward became acquainted with the specimens, called them "a rattlin' shower of witches' pebbles."

We also passed large surfaces of white rock, which were sprinkled all over with dark, hollow balls, of a vitrified substance. Most of them were imbedded midway in the rock, leaving a hemisphere exposed which, in color and form, was an exact counterpart of a large bomb. If the reader has ever seen a shell partly imbedded in the substance against which it was fired, this description will be perfectly plain. There were indications that a volcano had once existed in this vicinity, and it seemed highly probable that the red-hot balls which it projected into air had fallen and cooled in the soft formation adjacent, still retaining their original shape.

We should have lingered longer over these geological curiosities, had not the premonitory symptoms of a scientific lecture from the Professor alarmed our guide into the remonstrance, "You're burnin' daylight, gents!" and thus warned, we pushed forward.

A few hundred yards further brought us to the spot for commencing active operations. Dropping upon hands and knees, we began crawling along the side of the ravine in a line, pushing our guns before us. We knew that the buffalo must be very close, for we could hear the measured cropping of their teeth upon the grass. They seemed to be feeding toward us, as we slowly drew up to the level. I found myself trembling all over, so nervous that the cracking of a weed under our guns sounded to me as loud as a pistol-shot.

I looked around, and the stories which I had read in my youth of adventures in oriental lands rose fresh to my memory. I almost imagined our party a dozen wild Bedouins, creeping from ambush to fire upon a caravan, the first note of alarm to which would be a storm of musketry. Unshaven faces, soiled clothes, and rough hair, assisted us to the personation, and if aught else was needed to carry out the fancy, it soon came in a low "Hist!" from the guide, as he pointed to the level above us. Following the direction of his finger, we saw some hairy lumps, about the size of muffs, not fifty yards in front of us, bobbing up and down just above the line which defined the prairie's edge against the sky. For an instant, we supposed them to be small animals of some sort, playing on the slope, but the low voice of the guide said, "Thar they hump, gents!" and we caught the word at once, just as the whaler does the welcome cry of "There she blows," from the look-out aloft. What we saw, of course, were the humps of buffaloes moving slowly forward as they fed. At a word from our guide, we halted for last preparations.

"Fire at the nearest cows, gents," he said, "and if you get one down, and keep hid, you'll have lots of shots at the bulls gatherin' round."

Muggs was continually getting his gun crosswise, so that should it go off ahead of time, as usual, it would shoot somebody on the left, and kick some one on the right. Just ahead of us, a prairie dog sat on his castle wall, and barked constantly. But, fortunately, neither his signals nor our grumbled remonstrances to the Briton seemed to attract the attention of the herd in the least degree.

A few more feet of cautious crawling, and several buffaloes stood revealed, a cow and calf among the number. The mother espied us, and lifting her uncouth head, with its crooked, homely horns, regarded us for an instant with a quiet sort of feminine curiosity, and then went to feeding again. She probably considered us a parcel of sneaking wolves, and being conscious of having hosts of protectors near her, was not at all frightened. Almost simultaneously, the guns of the whole party were at shoulder, and just as the cow lifted her head again, to watch the movement, we fired. The fate of that bison was as effectually sealed as that of the condemned army horse which was first used to tell Paris and the world the terrors of the mitrailleuse. The poor creature gave a quick whirl to the right, made two convulsive jumps, and then stood still. She dropped her nose, a gush of blood following fast; her whole frame shuddered, as the air from the lungs tried to force its way through the clotted tide, and then she fell dead, almost crushing the calf also. The smell of the blood seemed to excite the bulls more than the report of the guns, which had only startled them for an instant. Some stood stupidly snuffing about the prostrate victim, while others, straightening out their tails, marched uneasily around.

Lying on the ground, and our heads only visible, we kept up a constant firing. It was almost impossible not to hit some of the old bulls. The veterans were wounded rapidly, and in all portions of their bodies. One old fellow, who had been standing with his rear to us, suddenly took it into his head to run for dear life, and away he went accordingly, with his hams looking very much like the end of a huge pepper-box. Two or three others soon began to show signs of grogginess, being drunk with the blood which was collecting internally from their many wounds.