полная версия

полная версияBuffalo Land

Talking thus about Indians, under the gloom of the trees, seemed in some unaccountable way to suggest the idea of witches to the mind of Pythagoras. Perhaps, in accordance with his pet theory of development, he was cogitating whether, ages ago, the red man's family horse might not have been a broomstick. At any rate, he suddenly gave a new turn to the conversation by asking Shamus why, when the dogs pointed the witch-hazel during our quail hunt at Topeka, he had affirmed that the canine race could see spirits and witches which to mortal eyes were invisible. Now, the Dobeen had been bred on an Irish moor, where the whole air is woven, like a Gobelin tapestry, full of dreams of the marvelous, and where whenever an unusual object is noticed by moonlight, the frightened peasant, instead of stopping a moment to investigate the cause, rushes shivering to his hut to tell of the fearful phookas he has seen. He was very superstitious, and we had often been amused at his evasions, when, as sometimes happened, his faith conflicted with our commands. The time might be near when such peculiarities would prove troublesome instead of amusing, and it was well, therefore, that we should get a peep at the foundations of our cook's faith, and perhaps that portion of it which related to our friends, the dogs, would be especially entertaining. Moreover, we had had so much of the red man that we were glad to welcome an Irish witch to our first camp-fire. Dobeen's narrative was substantially as follows, though I can not attempt to clothe it in his exact language, and still less in the rich brogue which yet clung to him after years of ups and downs in "Ameriky."

"Dogs can study out many things better than men can," said Shamus, in his most impressive manner. "Before I left old Ireland for America, I had a dashing beast, with as much wit as any boy in the country. He could poach a rabbit and steal a bird from under the gamekeeper's nose, an' give the swatest howl of warnin' whenever a bailiff came into them parts."

Sachem suggested that these were rather remarkable habits for a dog connected with the great house of Dobeen.

"But yez must know he was only a pup when my fortunes went by," responded Shamus, "and he learnt these tricks afterward. Ah, but he was a smart chap! Couldn't he smell bailiffs afore ever they came near, an' see all the witches and ghosts, too, by second sight! He wouldn't never go near the O'Shea's house, that had a haunted room, though pretty Mary, the house-girl, often coaxed at him with the nicest bits of meat."

Sachem thought that perhaps the animal's second sight might have shown him that stray shot from pretty Mary's master, aimed at a vagabond, might perhaps hit the vagabond's dog.

"I wasn't a vagabond them times," retorted Shamus, quickly, yet with entire good humor, "and sorry for it I am that the name could ever belong to me since. And please, Mr. Sachem, don't be after interruptin' again. Some people wonder why the dogs bark at the new moon an' howl under the windows afore a death. In the one matter, your honors, they see the witches on a broomstick, ridin' roun' the sky, an' gatherin' ripe moon-beams for their death-mixtures an' brain blights. Many a man in our grandfathers' time—yes, an' now-a-days too—sleepin' under the full moon, has had his brains addled by the unwholesome powder falling from the witches' aprons. Wise men call it comet dust. And why shouldn't a dog that has grown up to mind his duty of watchin' the family, howl when he sees Death sittin' on the window sill, a starin' within, and preparin' to snatch some darlint away? Ah, but their second sight is a wonderful gift though!

"The name of my dog, your honors, was Goblin, an' he came to us in a queer sort of way, just like a goblin should. There was a hard storm along the coast, an' the next mornin' a broken yawl drifted in, half full of water, with a dead man washin' about in it, an' a half-drowned pup squattin' on the back seat. Me an' my cousin buried the man, an' the other beast I brought up. May be there was somethin' in this distress that he got into so young that he couldn't outgrow. Even the priest used to notice it, and say the poor creature had a sort of touch of the melancholy; an' sure, he never was a joyful dog. Smart an' true he was, but, faith, he wasn't never happy; yez might pat him to pieces, an' get never a wag of the tail for it. He delighted in wakes and buryins, an' when a neighborin' gamekeeper died, he howled for a whole day an' a night, though the man had shot at him twenty times. Mighty few men, your honors, with a dozen slugs in their skin, would have stood on the edge of a man's grave that shot them, an' mourned when the earth rattled on the box the way Goblin, poor beast, did then. Ah, nobody knows what dogs can see with their wonderful second sight. That beast thought an' studied out things better than half the men ye'll find; an' it's my belief that dogs did so before, an' they have done it since, an' they always will."

"You are right, Dobeen," said the Professor. "Put a wise dog, and a foolish, vicious master together. The brute exhibits more tenderness and thoughtfulness than the man. In the latter, even the mantle of our largest charity is insufficient to cover his multitude of sins, while the skin of his faithful animal wraps nothing but honest virtue. The dog, having once suffered from poison, avoids tempting pieces of meat thenceforward, when proffered by strange hands, but the man steeps his brain in poison again and again—or as often as he can lay hold of it. While grasping the deadly thing, he sees, stretching out from the bar room door, a down grade road, with open graves at the end, and frightened madmen, chased by the blue devils and murder and misery, rushing madly toward them. These swallow their victims, as the hatches of a prison ship do the galley slave, and close upon them to give them up only when the jailer, the angel of the resurrection, shall unlock the tombs, and calls their occupants to judgment. Does the sight appall and bring him to his senses? No, he crowds among the terrors, and takes to his bosom the same venomous serpent that he has seen sting so many thousands to death before him. And yet people give to the brute's wisdom the name of instinct, and call man's madness wisdom."

"But, your honors," interposed Dobeen, "I shall be after losing my dog entirely, unless yez lave off interruptin' me, an' let me finish my story."

"Go on, Shamus, go on!" we all cried with one breath.

"Well, then, when Goblin came to me in his infancy, he wore a silver collar with his name all beautifully engraved on it. May be the dead man in the boat had been bringing him from some strange land to the childer at home, and thinking how the odd name would please them all, when the shadows were darting around his hearth. And so Goblin howled his way through the world, till one full moon eve, when every bog was shinin' as if the peat was silver. Such times, any way in old Ireland, your honors, the air is full of unwholesome spirits. This was good as a wake for Goblin, and I can just hear him now the way he cried and howled that night! He kept both eyes fixed on the moon, and no mortal man, livin' or dead, will ever know what he saw, but when he howled out worse nor common that night, it meant, may be, that some witch, uglier than the rest, had just whisked across the shinin' sky. Just at midnight, I was waked out of a swate sleep by the quietness without, the way a miller is when his mill stops. I looked out of the window at the dog where he sat, an', faith, the dog wasn't there at all! Just then I heard a despairin' sort of howl, away up in the air above the trees, an' by that token I knew the witches had Goblin. Next mornin', one of the lads livin' convanient to us told me he had heard the same cry in the middle of the night, the cry, your honors, of the poor beast as the witches carried him off. Afore the week was out, Goblin's collar was found on the gamekeeper's grave; that was all—not a hair else of him was ever seen in old Ireland."

As Shamus concluded his veracious narrative he looked around upon us with an air of triumph, as if satisfied that even Sachem dare not now dispute the second sight of the canine race.

That worthy took occasion to declare on the instant, however, that the nearest neighbor was fully justified in playing the witch. If any thing could destroy the happiness of human beings, as well as of the broom-riding beldams, it would be the howling of worthless curs at night. He himself had often been in at the death of vagabond cats and dogs engaged in moon-worship. The outbursts of Goblin had simply been silenced in an outburst of popular indignation.

SMASHING A CHEYENNE BLACK KETTLE.

CHAPTER XV

A FIRE SCENE—A GLIMPSE OF THE SOUTH—'COON HUNTING IN MISSISSIPPI—VOICES IN THE SOLITUDE—FRIENDS OR FOES—A STARTLING SERENADE—PANIC IN CAMP—CAYOTES AND THEIR HABITS—WORRYING A BUFFALO BULL—THE SECOND DAY—DAUB, OUR ARTIST—HE MAKES HIS MARK.

Our fire scene was evidently no novelty to the Mexicans, whose lives had been spent in camping out, and who, with one cheap blanket each, for mattress and covering, slept soundly under the wagons. Across their dark, expressionless faces the flames threw fitful gleams of light, which were as unheeded as the flashes with which the Nineteenth Century endeavors to penetrate the gloom which shrouds them as a nation. While the world moves on, the degenerate descendants of Montezuma sleep.

In the valley bordering our little skirt of trees we could hear the horses cropping the short, juicy buffalo grass, and trailing their lariat ropes around a circle, of which the pin was the center. Semi-Colon lay on the grass close to his father, who occupied a cracker-box seat in this tableau, the amiable son at little intervals raising his head to indorse, in his peculiar dissyllabic way, what the positive parent said. Looking at the group around me, and thinking of our evening turkey hunt, memory carried me back to the last time I had been among the trees after dark, with gun in hand, which was at the South, away down in Mississippi, just after the war.

It was a lazy time, those November days. Large flocks of swans filled the air above, with their flute-like notes, and thousands of sand-hill cranes circled far up toward the sun, their bodies looking like distant bees, as from dizzy heights they croaked their approbation of the rich crops beneath them. Ducks passed like charges of grape shot, sending back shrill whistles from their wings, as they dived down into the standing corn.

As night came on, the moon went up in a great rush of light, like the reflector of a railroad train mounting the sky. Soon every shadow is driven from the woods, and then the horns are tooted, the dogs howl, and away go gangs of woolly heads, old and young, in pursuit of Messrs. 'Possum and 'Coon. In vain the sly tree-fox doubles around stumps, and leaving tempting persimmon and oaks full of plumpest acorns, at the warning noise, seeks refuge among huge cypresses. On go the hunters—big dogs, little dogs, bear-teasers, and deer-hounds, sprinkled with darkeys—crashing through cane and underbrush, the human portion of the party laughing and yelling as if a tempest had stolen them ages ago from Babel, and just discharged them in pursuit of that particular 'coon.

The voice of the Professor suddenly called me back to the present, and I found myself chilled by the wet grass, as if my body had been wandering with the mind in that land of cotton, and was unprepared for the northern air.

"Gentlemen"—this was what the voice said—"we are now one thousand and five hundred miles from Washington City, latitude 39, longitude 99. Stick a pin there on the map, and you will find that we have got well out on the spot that geographers have been pleased to call desert. Does it look like one? Tell me, gentlemen, had you rather discount your manhood among the stumps of New England than loan it at a premium to the rich banks of these streams?"

The Professor came to an abrupt pause, for borne to us on the still air was that most unmistakable of all sounds, the human voice. The note of one bird at a distance may be mistaken for another, and the cry of a brute, when faintly heard, lose its distinguishing tones. But once let man lift up his voice in the solitude, and all nature knows that the lord of animal creation is abroad. There are many sounds which resemble the human voice, just as there are many objects which, indistinctly seen, the hunter's eye may misinterpret as birds. But when a flock of birds does cross his vision, however far away, he never mistakes them for any thing else. The first may have excited suspicion, the latter resolves at once into certainty.

We listened attentively and anxiously. It might very naturally be supposed that, after leaving the abodes of his fellows, and going far out into the solitary places of Nature, man would rejoice to catch the sounds which told him that others of his race were near, but this, like many other things, is modified by circumstances. On the plains the first question asked is, "Are they friends or foes?" No one being able to answer, the breeze and general probabilities are inquired of, and until the eyes pass verdict the moments are laden with suspense. Even in times of peace the hunter, if possible, avoids the savage bands which flit back and forth across Buffalo Land; for, if he saves his life, he is apt to lose an inconvenient amount of provisions, at least, at their hands.

Our guide speedily informed us that Indians never make any noise when in camp, which was gratifying intelligence. All further suspense was shortly relieved by the appearance down the valley of muskets glittering in the moon-light. The bearers proved to be two soldiers, who stated that some officers, with a small force of cavalry, were in camp a mile below us, being out for the purpose of obtaining buffalo meat, and having as guests two or three gentlemen from St. Louis, desirous of seeing the sport. They had heard our late heavy firing, and sent to know what was the matter. We gave the soldiers a late paper to carry back, and with many regrets that our fatigue was too great to think of accompanying them for a neighborly call, we bade them good-night, and saw them disappear down the valley.

At the Professor's suggestion, preparations were now made for retiring, and we sought our tent and blankets. In a few brief moments, the others of the party were blowing, in nasal trumpetings, the praises of Morpheus. I could not sleep, however; for each bone had its own individual ache, and was telling how tired it was. Pulling up a tent-pin, I looked out under the canvas.

On a log by the fire sat Shamus, his head between his hands, gazing at the coals, and droning a low tune. Occasionally, he would make a dash at some fire-brand, with a stick which he used as a poker, and break it into fragments, or toss it nervously to one side. Whether this was because it resolved itself into a fire-sprite winking at him, or some unhappy memory glowed out of the coals, I tried to tempt sleep by conjecturing.

Off at a little distance, I could see one of our men standing guard near the horses, and once or twice my excited fancy thought it detected shadows creeping toward him. A little beyond, nervously stretching his lariat rope, while walking in a circle around the pin, was Mr. Colon's Iron Billy. His clean head erect, and fine nose taking the breeze, the intelligent animal appeared restless, and I could not help thinking that he saw or smelt something unusual, away in the darkness. What if the bottom grass was full of creeping savages?

The crescent moon, just rising over the divide, was scarred by many cloud lines, and as yet gave no light. The sensation which had stolen over me was becoming disagreeable, when far off, at some ford down the creek, I heard animals splashing through water, and concluded that Billy's nervousness was caused by crossing buffaloes. The horse had an established reputation as a watch, his former owner having assured us that neither Indian nor wild beast could approach camp without Billy giving the alarm.

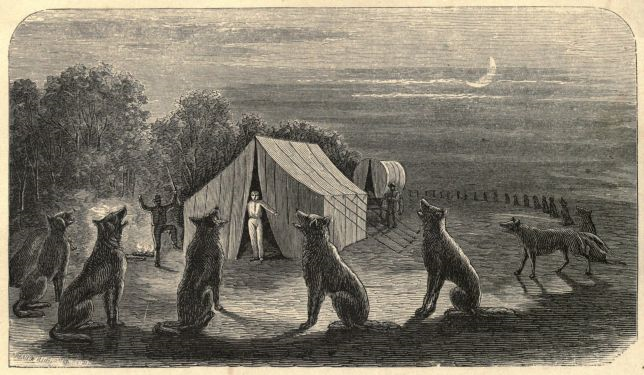

Presently, Dobeen resumed his droning, which had been suspended for a few moments, this time singing some snatches from an old Irish ballad. The last words were just dying away, when I started to my feet in horror. What an infernal chorus filled the air! Each point of the compass was represented, and we were wrapped around with a discordant, fiendish cordon of sound. Bursting upon us with a deep mocking cry, it ended abruptly in a wild "Ha-ha!" It was such a chorus as pours through Hades, when some poet opens, for an instant, the gate of the damned. Our poor Irishman, at the first sound, had fallen from the log as if shot, but had suddenly sprung to his feet, and was now performing a terror-dance behind the fire with a club. For a moment, I, too, had taken the outburst for the war-whoop of savages, but was saved from a panic by seeing through the gloom the figure of the sentinel still at his post, and the next instant the voice of the guide was lifted, with the re-assuring intelligence—"Only cayotes, gentlemen, only cayotes!"

Mr. Sachem and Mr. Muggs had been lying close behind me in their blankets. The former had given a terrified snort, and then both lay motionless. After the alarm, Sachem admitted that he was frightened. Had always heard that people shot over instead of under the mark in battle. Was resolved to lay low. Had no high views about such things. Muggs had not thought it worth while to get up. Knew they were wolves. Had heard more hextraordinary 'owls before he came to the blarsted country.

But where was the doctor? Echo answered, "Where?" "Hallo, Doctor!" cried the guide, and a voice from the woods, which was not echo, answered, "Coming!" Again Buffalo Bill lifted his voice in the solitude, and again came an answer, this time in a form of query, "Is it developed, my boy? If so, classify it." And we answered that the birth in the air had developed into wolves, and been classified as the canis latrans, noisy and harmless.

Finding that this new lesson in natural history had taken away all desire for sleep, I finished the study by the fire, with our guide for a tutor.

The cayote (pronounced Kī-o-te), in its habits, is a villainous cross between a jackal and a wolf, feasting on any kind of animal food obtainable, even unearthing corpses negligently buried. With the large gray wolf, the cayotes follow the herds of bison, generally skulking along their outskirts, and feeding upon the wounded and outcasts. These latter are the old bulls which, gaunt and stiff from age and spotted all over with scars, are driven out of the herd by the stout and jealous youngsters. Feeding alone, and weak with the burden of years upon his immense shoulders, the old bull is surrounded by the hungry pack. But they dare not attack. One blow of that ponderous head, with the weight of that shaggy hump behind it, is still capable of knocking down a horse. The veteran could fling his adversaries as nearly over the moon as the cow ever jumped, if they only gave him a chance. Like a grim old castle, he stands there more than a match for any direct assault of the army around.

MIDNIGHT SERENADE ON THE PLAINS.

With the tact of our modern generals, a line of investment is at once formed, and a system of worrying adopted. No rest now for the old bull. He can not lie down, or the beasts of prey will swarm upon him. Again and again he charges the foe, each time clearing a passage readily, but only to have it close again almost instantly. In these resultless sorties the garrison is fast using up its material of war. The ammunition is getting short which fires the old warrior, and sends the black horns, like a battering-ram, right and left among his foes. As long as he keeps his feet he lives, though hemmed in closely by the snapping and snarling multitude. The tenacity of one of these patriarchs is wonderful. For a whole life-time chief of the brutes on his native plains, he has grown up surrounded by wolves. Not fearing them himself, he has easily defended the cows and calves. An attempted siege would once have been but sport to him, and it seems difficult for the brain in the thick skull to understand that Time, like a vampire, has been sucking the juices from his joints and the blood from his veins.

Tired out at length, the old bull begins to totter, and his knees to shake from sheer exhaustion. His shakiness is as fatal as that of a Wall Street bull. As he lies down the wolves are upon him. They are clinging to the shaggy form, like blood-hounds, before it has even sunk to the sod, and the victim never rises again.

The cayotes are very cowardly, and when carcasses are plenty, sleep during the day in their holes, which are generally dug into the sides of some ravine. If found during the hours of light, it is usually skulking in the hollows near their burrows. They have a decidedly disagreeable penchant for serenading travelers' camps at night, so that our late experience, the guide assured me, was by no means uncommon. They will steal in from all directions, and sit quietly down on their haunches in a circle of investment. Not a sound or sign of their coming do they make, and, if on guard, one may imagine that every foot of the country immediately surrounding is visible, and utterly devoid of any animate object. All at once, as if their tails were connected by a telegraphic wire, and they had all been set going by electricity, the whole line gives voice. The initial note is the only one agreed upon. After striking that in concert, each particular cayote goes it on his own account, and the effect is so diabolical that I could readily excuse Shamus for thinking that the dismal pit had opened.

At this point Dobeen approached and cut off my further gleaning of wolf lore. The corners of his mouth seemed still inclined to twitch, showing that the shock had not yet worn off. He was chilled by the night, he said, and did not feel very well, and craved our honors' permission to sleep at our feet in the tent. Consent was given, and as he left us he turned to announce his belief that animals with such voices must have big throats.

It was not yet light, next morning, when our camp was all astir again. Drowsiness has no abiding place with an expedition like ours upon the plains. Should he be found lurking anywhere among the blankets, a bucket of water, from some hand, routs him at once and for the whole trip. Even Sachem, who usually hugged Morpheus so long and late, might that morning have been seen among the earliest of us washing in the waters of the creek.

We were all in excellent spirits, and with appetites for breakfast that would have done no discredit to a pack of hungry wolves. No sign of the sun was yet visible, save a scarcely perceptible grayish tinge diffusing itself slowly through the darkness, and the lifting of a light fog along the creek upon which we were encamped. Although sufficiently novel to most of our party, the scene was quite dreary, and we longed, amid the gloom and chill, for the appearance of the sun, and breakfast. By the way, I have noticed that with excursion parties, whether sporting or scientific, enthusiasm rises and sets with the sun. The gray period between darkness and dawn is an excellent time for holding council. The mind, no less than the body, seems to find it the coolest hour of the twenty-four, and shrinks back from uncertain advances.

Added to the discomforts usually attendant upon camp-life were our stiff joints. The first day upon horseback is twelve hours of pleasant excitement, with a fair share of wonder that so delightful a recreation is not indulged in more generally. The next twenty-four hours are spent in wondering whether those limbs which furnish one the means of locomotion are still connected with the stiffened body, or utterly riven from it; and, if the whole truth must be told, the saddle has also left its scars.

As the edge of the plateau overlooking the river became visible in the growing light, we saw, as on the evening previous, multitudes of buffalo feeding there, and after breakfast a council of war was held. I am somewhat ashamed to record that it voted no hunting that day. To find the noblest of American game some of us had come half away across the continent, and now, in sight of it, the tide of enthusiasm which had swept us forward hitherto stood suddenly still. Not because it was about to ebb, but simply in obedience to certain signals of distress flying from the various barks, and which it was utterly impossible for any of us to conceal.