полная версия

полная версияHow to make rugs

Shirt cuttings sell for about three cents per pound, and while a proportion of them are too small for use and would have to be re-sold for paper rags, the cost of material for cotton rugs would still be very trifling. Suitable woolen rags from the mills sell for twenty-five cents per pound. Tailors’ and dressmakers’ cuttings are much cheaper, and very advantageous arrangements can be made with large establishments if one is prepared to take all they have to offer.

One difficulty with woolen rags from tailoring establishments is in the sombreness of the colours; but much can be done by judicious sorting and sewing of the rags, for it is astonishing how bits of every conceivable colour will melt together when brought into a mixed mass; also if they are woven upon a red warp the effect is brightened.

Having secured materials of different kinds, the next step is in the cutting and sewing, and here also new methods must step in.

The old-fashioned way of sewing carpet rags—that is, simply tacking them together with a large needle and coarse thread—will not answer at all in this new development of rug making. The filling must be smooth, without lumps or rag ends, and the joinings absolutely fast and fairly inconspicuous. Some of the new rags from cotton or woolen mills come in pieces from a quarter to a half-yard in length and the usual width of the cloth. These can be sewed together on the sewing machine, lapping and basting them before sewing. They should lap from a quarter to a half inch and have two sewings, one at either edge of the lap. If sewed in this way they can afterward be torn into strips, using the scissors to cut across seams. It can be performed very speedily when one is accustomed to it, and is absolutely secure, so that no rag ends can ever be seen in the finished weaving.

If the cloth pieces which are to be used for rags are not wide enough to sew on the sewing machine, they should be lapped and sewed by hand in the same way, unless they happen to have selvedge ends, in which case they should by all means be strongly overhanded. This makes the best possible joining, as it is no thicker than the rest of the rag filling, and consequently gives an even surface. Good sewing is the first step toward making good and workmanlike rugs.

Whenever the rags can be torn instead of cut, it is preferable, as it secures uniform width. The width, of course, must vary according to the quality of cloth and weight desired in the rug. A certain weight is necessary to make it lie smoothly, as a light rug will not stay in place on the floor. In ordinary cotton cloth an inch wide strip is not too heavy and will pinch into the required space. If, however, a door-hanging or lounge-cover is being woven, the rags may be made half that width.

CHAPTER II.

THE PATTERN

When proper warp and filling are secured, experimental weaving may begin. If the loom is an old-fashioned wooden one, it will weave only in yard widths, and this yard width takes four hundred and fifty threads of warp. Warping the loom is really the only difficult or troublesome part of plain weaving, and therefore it is best to put in as long a warp as one is likely to use in one colour. One and a half pounds of cotton rags will make one yard of weaving.

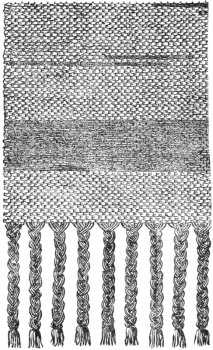

The simplest trial will be the weaving of white filling, either old or new, with a warp of medium indigo blue. Of course each warp must be long enough to weave several rugs; and the first one, to make the experiment as simple as possible, should be of white rags alone upon a blue warp. There must be an allowance of five inches of warp for fringe before the weaving is begun, and ten inches at the end of the rug to make a fringe for both first and second rugs. Sometimes the warp is set in groups of three, with a corresponding interval between, and this—if the tension is firm and the rags soft—gives a sort of honeycomb effect which is very good.

The grouping of the warp is especially desirable in one-coloured rugs, as it gives a variation of surface which is really attractive.

When woven, the rug should measure three feet by six, without the fringe. This is to be knotted, allowing six threads to a knot. This kind of bath-rug—which is the simplest thing possible in weaving—will be found to be truly valuable, both for use and effect. If the filling is sufficiently heavy, and especially if it is made of half-worn rags, it will be soft to the feet, and can be as easily washed as a white counterpane; in fact, it can be thrown on the grass in a heavy shower and allowed to wash and bleach itself.

Several variations can be made upon this blue warp in the way of borders and color-splashes by using any indigo-dyed material mixed with the white rags. Cheap blue ginghams, “domestics” or half-worn and somewhat faded blue denims will be of the right depth of color, but as a rule new denim is of too dark a blue to introduce with pure white filling.

The illustration called “The Onteora Rug” is made by using a proportion of a half-pound of blue rags to the two and a half of white required to make up the three pounds of cotton filling required in a six-foot rug. This half-pound of blue should be distributed through the rug in three portions, and the two and a half pounds of white also into three, so as to insure an equal share of blue to every third of the rug. After this division is made it is quite immaterial how it goes together. The blue rags may be long, short or medium, and the effect is almost certain to be equally good.

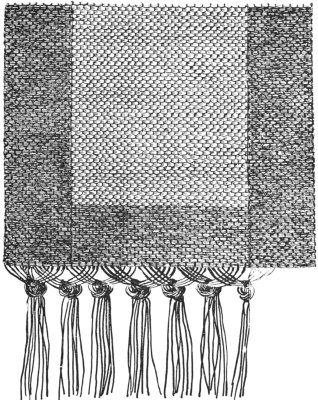

The side border in “The Lois Rug,” which is made upon the same blue warp, is separately woven, and afterward added to the plain white rug with blue ends, but an irregular side border can easily be made by sewing the rags in lengths of a half-yard, alternating the blue and white, and keeping the white rags in the centre of the rug while weaving.

These three or four variations of style in what we may call washable rugs are almost equally good where red warp is used, substituting Turkey red rags with the white filling instead of blue. An orange warp can be used for an orange and white rug, mixing the white filling with ordinary orange cotton cloth.

The effect may be reversed by using a white warp with a red, blue or yellow filling, making the borders and splashes with white. One of the best experiments in plain weaving I have seen is a red rug of the “Lois” style, using white warp and mixed white and green gingham rags for the borders, while the body of the rug is in shaded red rags.

This, however, brings us to the question of color in fillings, which must be treated separately.

THE ONTEORA RUG

Of course, variations of all kinds can be made in washable rugs. Light and dark blue rags can be used in large proportion with white ones to make a “hit or miss,” and where a darker rug is considered better for household use it can be made entirely of dark and light blue on a white warp; the same thing can be done in reds, yellows and greens. Brown can be used with good effect mixed with orange, using orange warp; or orange, green and brown will make a good combination on a white warp. In almost every variety of rug except where blue warp is used a red stripe in the border will be found an improvement.

A very close, evenly distributed red warp, with white filling, will make a pink rug good enough and pretty enough for the daintiest bedroom. If it is begun and finished with a half-inch of the same warp used as filling, it makes a sort of border; and this, with the red fringe, completes what every one will acknowledge is an exceptionally good piece of floor furnishing.

In using woolen rags, which are apt to be much darker in colour than cotton, a white, red or yellow warp is more apt to be effective than either a green or a blue; in fact, it is quite safe to say that light filling should go with dark warp and dark filling with light or white.

There is an extremely good style of rag rug made at Isle Lamotte, in Vermont, where very dark blue or green woolen rags are woven upon a white warp, with a design of arrows in white at regular intervals at the sides. This design is made by turning back the filling at a given point and introducing a piece of white filling, which in turn is turned back when the length needed for the design is woven and another dark one introduced, each one to be turned back at the necessary place and taken up in the next row. Of course, while the design is in progress one must use several pieces of filling in each row of weaving.

The black border can only be made by introducing a large number of short pieces of the contrasting colour which is to be used in the design and tacking them in place as the weaving proceeds. Of course, in this case thin cloth should be used for the colour-blocks, as otherwise the doubling of texture would make an uneven surface. If the rug is a woolen one, not liable to be washed, this variation of color in pattern can be cleverly made by brushing the applied color pieces lightly with glue. Of course, in this case the design will show only on the upper side of the rug. In fact, the only way to make the design show equally on both sides is by turning back the warp, as in the arrow design, or by actually cutting out and sewing in pieces of colour.

By following out the device of using glue for fastening the bits of colour which make border designs many new and very interesting effects can be obtained, as most block and angle forms can be produced by lines made in weaving. It is only where the rug must be constantly subject to washing that they are not desirable. It must be remembered that the warp threads bind them into place, after they are glue-fastened.

Large rugs for centres of rooms can be made of woolen rags by weaving a separate narrow border for the two sides. If the first piece is three feet wide by eight in length, and a foot-wide border is added at the sides, it will make a rug five feet wide by eight feet long; or if two eight-foot lengths are sewn together, with a foot-wide border, it will make an eight-by-eight centre rug. The border should be of black or very dark coloured filling. In making a bordered rug, two dark ends must be woven on the central length of the rug—that is, one foot of black or dark rags can be woven on each end and six feet of the “hit or miss” effect in the middle. This gives a strip of eight feet long, including two dark ends. The separate narrow width, one foot wide and sixteen feet in length, must be added to this, eight feet on either side. The border must be very strongly sewn in order to give the same strength as in the rest of the rug.

The same plan can be carried out in larger rugs, by sewing breadths together and adding a border, but they are not easily lifted, and are apt to pull apart by their own weight. Still, the fact remains that very excellent and handsome rugs can be made from rags, in any size required to cover the floor of a room, by sewing the breadths and adding borders, and if care and taste are used in the combinations as good an effect can be secured as in a much more costly flooring.

The ultimate success of all these different methods of weaving rag rugs depends upon the amount of beauty that can be put into them. They possess all the necessary qualities of durability, usefulness and inexpensiveness, but if they cannot be made beautiful other estimable qualities will not secure the wide popularity they deserve. Durable and beautiful colour will always make them salable, and good colour is easily attainable if the value of it is understood.

There are two ways of compassing this necessity. One is to buy, if possible, in piece ends and mill waste, such materials as Turkey red, blue and green ginghams, and blue domestics and denims, as well as all the dark colours which come in tailors’ cuttings. The other and better alternative is to buy the waste of white cotton mills and dye it. For the best class of rugs—those which include beauty as well as usefulness, and which will consequently bring a much larger price if sold—it is quite worth while to buy cheap muslins and calicoes; and as quality—that is, coarseness or fineness—is perfectly immaterial, it is possible to buy them at from four to five cents per yard. These goods can be torn lengthwise, which saves nearly the whole labor of sewing them, and from eight to ten yards, according to their fineness, will make a yard of weaving. The best textile for this is undoubtedly unbleached muslin, even approaching the quality called “cheesecloth.” This can easily be dyed if one wishes dark instead of light colours, and it makes a light, strong, elastic rug which is very satisfactory.

In rag carpet weaving in homesteads and farmhouses—and it is so truly a domestic art that it is to be hoped this kind of weaving will be confined principally to them—some one of the household should be skilled in simple dyeing. This is very important, as better and cheaper rugs can be made if the weaver can get what she wants in colour by having it dyed in the house, rather than by the chance of finding it among the rags she buys.

CHAPTER III.

DYEING

In the early years of the past century a dye-tub was as much a necessity in every house as a spinning wheel, and the re-establishment of it in houses where weaving is practised is almost a necessity; in fact, it would be of far greater use at present than in the days when it was only used to dye the wool needed for the family knitting and weaving. All shades of blue, from sky-blue to blue-black, can be dyed in the indigo-tub; and it has the merit of being a cheap as well as an almost perfectly fast dye. It could be used for dyeing warps as well as fillings, and I have before spoken of the difficulty, indeed almost impossibility, of procuring indigo-dyed carpet yarn.

Blue is perhaps more universally useful than any other colour in rag rug making, since it is safe for both cotton and wool, and covers a range from the white rug with blue warp, the blue rug with white warp, through all varieties of shade to the dark blue, or clouded blue, or green rug, upon white warp. It can also be used in connection with yellow or orange, or with copperas or walnut dye, in different shades of green; and, in short, unless one has exceptional advantages in buying rags from woolen mills, I can hardly imagine a profitable industry of rag-weaving established in any farmhouse without the existence of an indigo dyeing-tub.

REDThe next important color is red. Red warps can be bought, but the lighter shades are not even reasonably fast; and indeed, the only sure way of securing absolutely fast colour in cotton warp is to dye it. Prepared dyes are somewhat expensive on account of the quantity required, but there are two colours, Turkey red and cardinal red, which are extremely good for the purpose. These can be brought at wholesale from dealers in chemicals and dye-stuffs at much cheaper rates than by the small paper from the druggist.

COPPERASThe ordinary copperas, which can be bought at any country store, gives a fast nankeen-coloured dye, and this is very useful in making a dull green by an after-dip in the indigo-tub.

WALNUTThere are some valuable domestic dyes which are within the reach of every country dweller, the best and cheapest of which is walnut or butternut stain. This is made by steeping the bark of the tree or the shell of the nut until the water is dark with colour. It will give various shades of yellow, brown, dark brown and green brown, according to the strength of the decoction or the state of the bark or nut when used. If the bark of the nut is used when green, the result will be a yellow brown; and this stain is also valuable in making a green tint when an after-dip of blue is added. Leaves and tree-bark will give a brown with a very green tint, and these different shades used in different rags woven together give a very agreeably clouded effect. Walnut stain will itself set or fasten some others; for instance, pokeberry stain, which is a lovely crimson, can be made reasonably fast by setting it with walnut juice.

RUST-COLOURIron rust is the most indelible of all stains besides being a most agreeable yellow, and it is not hard to obtain, as bits of old iron left standing in water will soon manufacture it. It would be a good use for old tin saucepans and various other house utensils which have come to a state of mischievousness instead of usefulness.

GRAYInk gives various shades of gray according to its strength, but it would be cheaper to purchase it in the form of logwood than as ink.

LOGWOOD CHIPSLogwood chips boiled in water give a good yellow brown—deep in proportion to the strength of the decoction.

YELLOW FROM FUSTICYellow from fustic requires to be set with alum, and this is more effectively done if the material to be dyed is soaked in alum water and dried previous to dyeing. Seven ounces of alum to two quarts of water is the proper proportion. The fustic chips should be well soaked, and afterward boiled for a half-hour to extract the dye, which will be a strong and fast yellow.

ORANGEOrange is generally the product of annato, which must be dissolved with water to which a lump of washing soda has been added. The material must be soaked in a solution of tin crystals before dipping, if a pure orange is desired, as without this the color will be a pink buff—or “nankeen” color.

What I have written on the subject of home dyeing is intended more in the way of suggestion than direction, as it is simply giving some results of my own experiments, based upon early familiarity with natural growths rather than scientific knowledge. I have found the experiments most interesting, and more than fairly successful, and I can imagine nothing more fascinating than a persistent search for natural and permanent dyes.

The Irish homespun friezes, which are so dependable in colour for out-of-door wear, are invariably dyed with natural stains, procured from heather roots, mosses, and bog plants of like nature. It must be remembered that any permanent or indelible stain is a dye, and if boys and girls who live in the country were set to look for plants possessing the colour-quality, many new ones might be discovered. I am told by a Kentucky mountain woman, used to the production of reliable colour in her excellent weaving, that the ordinary roadside smartweed gives one of the best of yellows. Indeed, she showed me a blanket with a yellow border which had been in use for twenty years, and still held a beautiful lemon yellow. In preparing this, the plant is steeped in water, and the tint set with alum. Combining this with indigo, or by an after-dip in indigo-water, one could procure various shades of fast blue-green, a colour which is hard to get, because most yellows, which should be one of its preparatory tints, are buff instead of lemon yellow.

An unlimited supply and large variety of cheap and reliable colour in rag filling, and a few strong and brilliant colours in warps, are conditions for success in rag rug weaving, but these colours must be studiously and carefully combined to produce the best results.

I have said that, as a rule, light warps must go with dark filling and dark warps with light, and I will add a few general rules which I have found advantageous in my weaving.

In the first place, in rugs which are largely of one colour, as blue, or green, or red, or yellow, no effort should be made to secure even dyeing; in fact, the more uneven the colour is the better will be the rug. Dark and light and spotted colour work into a shaded effect which is very attractive. The most successful of the simple rugs I possess is of a cardinal red woven upon a white warp. It was chiefly made of white rags treated with cardinal red Diamond dye, and was purposely made as uneven as possible. The border consists of two four-inch strips of “hit or miss” green, white and red mixed rags, placed four inches from either end, with an inch stripe of red between, and the whole finished with a white knotted fringe.

A safe and general rule is that the border stripes should be of the same colour as the warp—as, for instance, with a red warp a red striped border—while the centre and ends of the rug might be mixed rags of all descriptions.

It is also safe to say that in using pure white or pure black in mixed rags, these two colours, and particularly the white, should appear in short pieces, as otherwise they give a striped instead of a mottled effect, and this is objectionable. White is valuable for strong effects or lines in design; indeed, it is hard to make design prominent or effective except in white or red.

THE LOIS RUG

These few general rules as to colour, together with the particular ones given in other chapters, produce agreeable combinations in very simple and easy fashion. I have not, perhaps, laid as much stress upon warp grouping and treatment as is desirable, since quite distinct effects are produced by these things. Throwing the warp into groups of three or four threads, leaving small spaces between, produces a sort of basket-work style; while simply doubling the warp and holding it with firm tension gives the honeycomb effect of which I have previously spoken. If the filling is wide and soft, and well pushed back between each throw of the shuttle, it will bunch up between the warp threads like a string of beads, and in a dark warp and light filling a rim of coloured shadow seems to show around each little prominence. Such rugs are more elastic to the tread than an even-threaded one, and on the whole may be considered a very desirable variation.

It is well for the weaver to remember that every successful experiment puts the manufacture on a higher plane of development and makes it more valuable as a family industry.

CHAPTER IV.

INGRAIN CARPET RUGS

Undoubtedly the most useful—and from a utilitarian point of view the most perfect—rag rug is made from worn ingrain carpet, especially if it is of the honest all-wool kind, and not the modern mixture of cotton and wool. There are places in the textile world where a mixture of cotton and wool is highly advantageous, but in ingrain carpeting, where the sympathetic fibre of the wool holds fast to its adopted colour, and the less tenacious cotton allows it to drift easily away, the result is a rusty grayness of colour which shames the whole fabric. This grayness of aspect cannot be overcome in the carpet except by re-dyeing, and even then the improvement may be transitory, so an experienced maker of rugs lets the half-cotton ingrain drift to its end without hope of resurrection.

The cutting of old ingrain into strips for weaving is not so serious a task as it would seem. Where there is an out-of-doors to work in, the breadths can easily be torn apart without inconvenience from dust. After this they should be placed, one at a time, in an old-fashioned “pounding-barrel” and invited to part with every particle of dust which they have accumulated from the foot of man.

For those who do not know the virtues and functions of the “pounding-barrel,” I must explain that it is an ordinary, tight, hard-wood barrel; the virtue lying in the pounder, which may be a broom-handle, or, what is still better, the smooth old oak or ash handle of a discarded rake or hoe. At the end of it is a firmly fixed block of wood, which can be brought down with vigour upon rough and soiled textiles. It is an effective separator of dust and fibre, and is, in fact, a New England improvement upon the stone-pounding process which one sees along the shores of streams and lakes in nearly all countries but England and America.

If the pounding-barrel is lacking, the next best thing is—after a vigorous shaking—to leave the breadths spread upon the grass, subject to the visitations of wind and rain. After a few days of such exposure they will be quite ready to handle without offense. Then comes the process of cutting. The selvages must be sheared as narrowly as possible, since every inch of the carpet is valuable. When the selvages are removed, the breadths are to be cut into long strips of nearly an inch in width and rolled into balls for the loom. If the pieces are four or five yards in length, only two or three need to be sewn together until the weaving is actually begun, as the balls would otherwise become too heavy to handle. As the work proceeds, however, the joinings must be well lapped and strongly sewn, the rising of one of the ends in the woven piece being a very apparent blemish.