полная версия

полная версияRemarks on some fossil impressions in the sandstone rocks of Connecticut River

John Collins Warren

Remarks on some fossil impressions in the sandstone rocks of Connecticut River

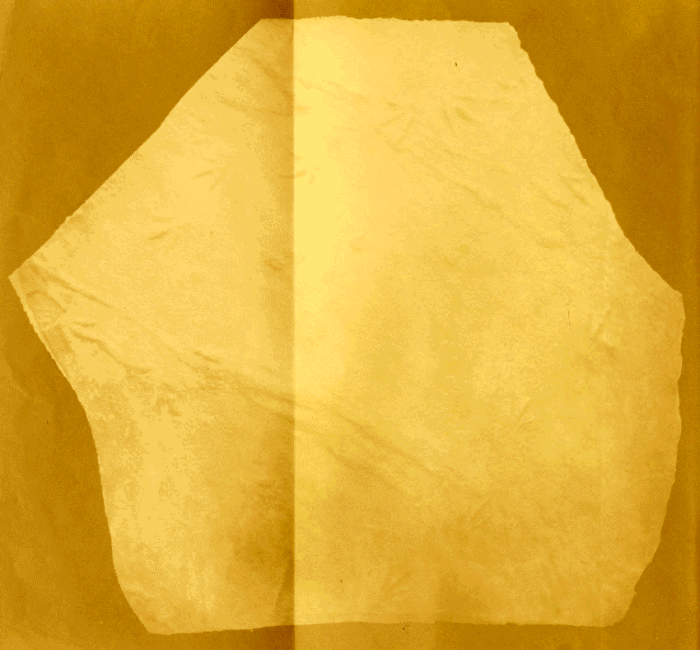

Plate: Image of sandstone slab with fossil track and footprint impressions.

The principal part of these remarks were made at the meetings of the Boston Society of Natural History. A portion of them also have been printed in the Proceedings of the Society.

The object of this publication is to afford to those who are not members of the Society an opportunity of obtaining some knowledge of Fossil Impressions, which they might not be able to obtain elsewhere so conveniently.

Some account of the Epyornis seems to be very properly connected with Ornithichnites.

The first of these papers was written in October, 1853; the others in the earlier part of the present year.

THE EPYORNIS;OR,

GREAT BIRD OF MADAGASCAR, AND ITS EGGS

In the course of the year 1851, an account was circulated of the discovery of an immense egg, or eggs, in the Island of Madagascar. The size of the eggs spoken of was so disproportionate to that of any previously known, that most persons received the account with incredulity; and, I must confess, I was one of this number. Being in Paris soon after hearing of this report, I made inquiry on the subject, and was surprised to learn, that the great egg was actually existing in the Museum of Natural History in Paris. In a few days I had an opportunity of seeing a cast of it in the hands of the artist, M. Strahl, of whom I solicited one. He informed me that it could not be obtained at that moment; but that, if my request were made known to the Administration of the Museum, he had no doubt they would accede to it. I accordingly did apply, and also presented them with the cast of a perfect head of Mastodon Giganteus; and they very liberally granted my request.

The distinguished naturalist, Professor Geoffroy St. Hilaire, the second of that honorable name, has made a statement to the Academy of Sciences, which, though only initiatory, contains many facts of a very interesting nature, some of which I have had an opportunity of verifying; and to him we are indebted for a greater part of the others.

The eggs sent to me are, in number, two; one of which was purchased by M. Abadie, captain of a French vessel, from the natives. Another was soon afterwards found, equal in size. A third egg was discovered in an alluvial stratum near a stream of water, together with other valuable relics of the animal which had probably produced them; but, unfortunately, it was broken during transportation. Of the two eggs, one is of an ovoid form, having much the shape of a hen's egg; and the other is an ellipsoid.

The ovoid egg is of enormous size, even when compared with the largest egg we are acquainted with. Its long diameter exceeds thirteen inches of our English measure, its short diameter eight, and its long circumference thirty-three inches. Its capacity is thought to be equal to eighteen liquid pints, or to be six times greater than that of the largest egg known to us (the ostrich), although but twice its length. It is said to be equal to a hundred and forty-eight hen eggs. The ellipsoid egg has its longest diameter somewhat less than that of the ovoid; its short diameter nearly equals that of the other egg, being more than eight inches. The third egg, although broken, has been very useful to science, by displaying the thickness of the shell, which is about one-tenth of an inch.

The bones, of which I have received the casts, are three in number, and of great interest. One of them is a characteristic fragment of the upper part of a fibula; the other two, still more interesting, as enabling us to determine the class and genus of the animal to which they belong, exhibit the extremities of the right and left tarso-metatarsal bones. The former is somewhat broken; the latter is nearly perfect, and exhibits the triple division of the inferior extremity of the bone into the three trochleæ or pulley-shaped processes of the struthious birds. It might be mistaken for a bone of the great Dinornis, but is distinguished from this by the flatness of the portion above the trochleæ. Still less is it one of the bones of the ostrich, its three pulleys being separated from each other by distinct intervals; whereas the pulleys of the ostrich have only one such separation, constituting two distinct eminences.

M. Geoffroy St. Hilaire considered himself justified, from these and other facts, in deciding this bone to belong to a bird of a new genus, to which he gives the name of Epyornis, from αἰπύς, high, tall, and ὄρνις, bird; and, as probably it is a specimen of the largest animal of the family, he affixes the specific name of maximus.

The size of this bird, inferred from that of its egg, would be vastly superior to that of the ostrich. But if we notice the comparative size of the trochleated extremity of the tarso-metatarsal bone, we shall see that its height would be greatly exaggerated by adopting such a basis for its establishment; in fact, it would not probably exceed a height double that of the ostrich. And, though it must have been superior to that of the Dinornis maximus of Prof. Owen, it might perhaps excel it only by the difference of two or three feet. A bird of twelve or thirteen feet in height would, however, if we stood in its presence, appear enormous, and must have greatly astonished and terrified the natives of Madagascar. Whether it now exists is uncertain, as it may possibly have a habitation in the wild recesses of the island, which have never yet been visited by any European traveller.

The credit of most of the observations and discoveries relating to this remarkable bird is attributable to French naturalists;1 and it seems to be a duty devolving on English and American navigators to complete the history thus happily begun, and to tell us whether the Epyornis still exists in the mountain-forests of Madagascar, or at least present us with its extraordinary relics.

FOSSIL IMPRESSIONS.—I

Ichnology, a newly created branch of science, takes its name from the Greek word ἴχνος , a track or footstep, and the tracks themselves have been denominated Ichnites, or, when they refer to birds only, Ornithichnites, from ὄρνις, a bird. And this last term has by custom been generally applied to ancient impressions, though not correctly.

Geology has revealed to us not only the remains of animals and vegetables, but the impressions made by them during their lives, and even the impressions of unorganized bodies. The first notice of these appearances was, as often happens, regarded with indifference or scepticism; but their number and variety enlightened the public mind, and opened a new source of information and improvement.

The first remarkable observation made on fossil footsteps was that of the Rev. Dr. Duncan, of Scotland, in 1828. He noticed, in a new red sandstone quarry in Dumfriesshire, impressions of the feet of small animals of the tortoise kind, having four feet, and five toes on each foot. They were seen in various layers through a thickness of forty feet or more.

Sandstone, in which these impressions are principally discovered, is a rock composed chiefly of siliceous and micaceous particles cemented together by calcareous or argillaceous paste, containing salt, and colored with various shades of the oxide of iron, particularly the red, gray, brown. It has been remarked by Prof. H. D. Rogers, that the perfection of the surface containing fossil footmarks is often attributable to a micaceous deposit. The layers of sandstone have been formed by deposits from sea-water, dried in succession; such layers are also seen in the roofing slate. These deposits on the shores of the ocean, having in a soft condition received the impressions of the feet of birds, other animals, vegetables, and also of rain-drops, under favorable circumstances dried, hardened, and formed a rock of greater or less solidity. Our colleague, Dr. Gould, has exhibited to us a specimen of dried clay from the shores of the Bay of Fundy, containing beautiful impressions, recently made, of the footsteps of birds. The particles brought by the waves, and deposited in the manner described, were derived from the destruction of other rocks previously existing, particularly granite and flint, or silex, the shining atoms of which compose no small part of the sandstone rock.

It is easy to conceive, that, while these deposits were taking place in the soft condition, portions of vegetable matters might become intermixed; and that these, with the impressions of the feet and other parts of animals and unorganized substances, might be preserved by the process of desiccation. The agency of internal heat may have also been employed in some cases in baking and hardening these crusty layers.

The sandstone rock, though in some places actually in a state of formation at the present time, lies in such a manner in the earth's crust as to indicate an immense antiquity. The age of these beds varies in different situations. The sandstone rocks which contain the greater part of the impressions are called new red sandstone, to distinguish them from the old red, which is of a greater age. The deposits on Connecticut River may not be attributed to the action of this river, but are of higher antiquity, probably, than the river itself, and proceeded from the waves of an ancient sea, existing in a state of the surface of the globe very different from that of the present day.

In 1834, tracks were discovered near Hildberghausen in Saxony, to which Prof. Kaup, of Darmstadt, gave the name of Chirotherium, from the resemblance to the impressions of the human hand. On a subsequent examination, Prof. Owen preferred the name of Labyrinthodon, from the resemblance of the folds in the teeth to the convolutions of the brain.

Various other instances of impressions were seen; and, in the year 1835, Dr. Deane and Mr. Marsh, residents of Greenfield, noticed impressions resembling the feet of birds in sandstone rocks of that neighborhood. These observations having come to the knowledge of President Hitchcock, of Amherst College, that gentleman began a thorough investigation of the subject, followed it up with unremitted ardor, and has, since 1836 (the date of his first publication), laid before the public a great amount of ichnological information, and really created a new science. Dr. Deane, on his part, has not been idle: besides making valuable discoveries, he has written a number of excellent papers to record some portion of his numerous observations.

In 1837, at the request of my friend Dr. Boott, I carried to London, for the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons, various scientific objects peculiar to this country; among which were a number of casts of Ornithichnites.

These casts were kindly furnished me by President Hitchcock, and the Government of the Royal College thereon voted to present to President Hitchcock and Amherst College casts of the skeleton of the famous Megatherium of South America. These casts were packed, and sent to be embarked in a ship destined for Boston, but were unluckily delivered to a wrong shipping house in London, and I lost sight of them for some time. They were at length discovered. After remaining in this situation for more than a year, they were sold at public auction; and, notwithstanding many efforts on my part, I was unable to obtain and transmit them to Amherst College.

The fossil impressions which have been distinguished in various places in the new red sandstone are those of birds, frogs, turtles, lizards, fishes, mollusca, crustacea, worms, and zoophytes. Besides these, the impressions made by rain-drops, ripple-marks in the sand, coprolites or indurated remains of fæces of animals, and even impressions of vegetables, have been preserved and transmitted from a remote antiquity. No authentic human impressions have yet been established; and none of the mammalia, except the marsupials.(?) We must, however, remember that, although the early paleontology contains no record of birds, the ancient existence of these animals is now fully ascertained. Remains of birds were discovered in the Paris gypsum by Cuvier previous to 1830. Since that time, they have been found in the Lower Eocene in England, and the Swiss Alps; and there is reason to believe that osseous relics may be met with in the same deposits which contain the foot-marks. Most of the bird-tracks which have been observed, belong to the wading birds, or Grallæ.

The number of toes in existing birds varies from two to five. In the fossil bird-tracks, the most frequent number is three, called tridactylous; but there are instances also of four or tetradactylous, and two or didactylous. The number of articulations corresponds in ornithichnites with living birds: when there are four toes, the inner or hind toe has two articulations, the second toe three, the third toe four, the outer toe five. The impressions of the articulations are sometimes very distinct, and even that of the skin covering them.

President Hitchcock has distinguished more than thirty species of birds, four of lizards, three of tortoises, and six of batrachians.

The great difference in the characters of many fossil animals from those of existing genera and species, in the opinion of Prof. Agassiz, makes it probable that in various instances the traces of supposed birds may be in fact traces of other animals, as, for example, those of the lizard or frog. And he supports this opinion, among other reasons, by the disappearance of the heel in a great number of Ornithichnites.

D'Orbigny, to whom we are indebted for the most ample and systematic work on Paleontology ("Cours Elémentaire de Paléontologie et de Géologie," 5 vols. 1849-52), does not accept the arrangement of President Hitchcock. He objects to the term Ornithichnites, and proposes what he considers a more comprehensive arrangement into organic, physiological, and physical impressions. Organic impressions are those which have been produced by the remains of organized substances, such as vegetable impressions from calamites, &c. Physiological impressions are those produced by the feet and other parts of animals. Physical impressions are those from rain-drops and ripple-marks; and to these may be added coprolites in substance. This plan of D'Orbigny seems to exclude the curious and interesting distinctions of groups, genera, and species; in this way diminishing the importance of the science of Ichnology.

Fossil impressions have been found on this continent in the carboniferous strata of Nova Scotia, and of the Alleghenies; in the sandstone of New Jersey, and in that of the Connecticut Valley in a great number of places, from the town of Gill in Massachusetts to Middletown in Connecticut, a distance of about eighty miles.

A slab from Turner's Falls, obtained for me by Dr. Deane in 1845, measuring two feet by two and a half, and two inches in thickness, contains at least ten different sets of impressions, varying from five inches in length to two and a half, with a proportionate length of stride from thirteen inches to six. All these are tridactylous, and represent at least four different species. In most of them the distinction of articulation is quite clear. The articulations of each toe can readily be counted, and they are found to agree with the general statement made above as to number. The impressions are singularly varied as to depth; some of them, perfectly distinct, are superficial, like those made by the fingers laid lightly on a mass of dough, while others are of sufficient depth nearly to bury the toes; some of the tracks cross each other, and, being of different sizes, belong to animals of different ages or different species. There is one curious instance of the tracks of a large and heavy bird, in which, from the softness of the mud, the bird slipped in a lateral direction, and then gained a firm footing; the mark of the first step, though deep, is ill-defined and uncertain; the space intervening between the tracks is superficially furrowed; in the settled step, which is the deepest, the toes are very strongly indicated. On the same surface are impressions of nails, which may have belonged to birds or chelonians.

The inferior surface of the same slab exhibits appearances more superficial, less numerous, but generally regular. There are three sets of tracks entirely distinct from each other; two of them containing three tracks, and one containing two,—the latter being much the largest in size. In addition, there is one set of tracks, which are probably those of a tortoise. These marks present two other points quite observable and interesting. One is that they are displayed in relief, while those on the upper surface are in depression. The relief in this lower surface would be the cast of a cavity in the layer below; so the depressions in the upper surface would be moulds of casts above. The second point is the non-correspondence of the upper and lower surfaces; i.e. the depressions in the upper surface have not a general correspondence with the elevations on its inferior surface. The tracks above were made by different individuals and different species from those below. This leads to another interesting consideration, that in the thickness of this slab there must be a number of different layers, and in each of them there may be a different series of tracks.

To these last remarks there is one exception: the deep impression in which the bird slipped in a lateral direction corresponds with an elevation on the lower surface, in which the impression of these toes is very distinctly displayed, and even the articulations. Moreover, one of the tracks on the inferior surface interferes with the outer track in the superior, and tends in an opposite direction, so that this last-described footstep must have been made before the other. It is also observable, that, while all the other tracks are superficial, this last penetrates the whole thickness of the slab; thus showing that the different deposits continued some time in a soft state.

On the surfaces of this slab, particularly on the upper, there are various marks besides those of the feet, some of which seem to have been made by straws, or portions of grass, or sticks; and there is a curved line some inches in length, which seems to have arisen from shrinkage.

In the collection of Mr. Marsh,2 there were two slabs of great size, each measuring ten by six feet, having a great number of impressions of feet, and about the same thickness as the slab under examination. One of these presented depressions; and the other, corresponding reliefs. These very interesting relations were necessarily parted in the sale of Mr. Marsh's collection; one of them being obtained for the Boston Society of Natural History, and the other for the collection of Amherst College.

The Physical Impressions, according to Professor D'Orbigny, are of three kinds, viz.: 1st, Rain-drops; 2d, Ripple-marks; and 3d, Coprolites. I have a slab which exhibits two leptodactylous tracks very distinct, about an inch and a half long, surrounded by impressions of rain-drops and ripple-marks. Another specimen exhibits the impressions of rain in a more distinct and remarkable manner. The imprints are of various sizes, from those which might be made by a common pea to others four times its diameter; some are deep, others superficial and almost imperceptible. They are generally circular, but some are ovoid. Some have the edge equally raised around, as if struck by a perpendicular drop; and others have the edge on one part faintly developed, while another part is very sharp and well defined, as if the drop had struck obliquely. It has been suggested, that these fossil rain-drops may have been made by particles of hail; but I think the variety of size and depth of depression would have been more considerable if thus made.

Although we have necessarily treated the subject of fossil footmarks in a very brief way, sufficient has been said to show that this new branch of Paleontology may lead to interesting results. The fact that they are, in some manner, peculiar to this region, seems to call upon our Society to obtain a sufficient number of specimens to exhibit to scientific men a fair representation of the condition of Ichnology in this quarter of our country; and we have therefore great reason to congratulate ourselves, that, through the vigilance and spirit of our members, the Society has the expectation of obtaining a rich collection of ichnological specimens.

FOSSIL IMPRESSIONS.—II

Since writing the preceding article, I have been able to obtain, through the kindness of President Hitchcock, a number of additional specimens of fossil impressions. By the aid of these, I may hope to give an idea of the system of impressions, so far as it has been discovered, without, however, attempting to enter into minute details. For these, I would refer to the account of the "Geology of Massachusetts," by President Hitchcock; to his valuable article published in the "Memoirs of the American Academy;" and to his geological works generally.

The numerous tracks which have been assembled together in the neighborhood of Connecticut River have afforded an opportunity of prosecuting these studies to an extent unusual in the primitive rocky soil of New England. These appearances are not, indeed, wholly new. Such traces had been previously met with in other countries; but, in their number and variety, the valley of the Connecticut abounds above all places hitherto investigated.

Twenty years have elapsed since the study of Ichnology has been prosecuted in this country; and, in this period of time, about forty-nine species of animal tracks have been distinguished in the locality mentioned, according to President Hitchcock; which have been regularly arranged by him in groups, genera, and species.

I propose now to lay the specimens, recently obtained, before the Society, as a slight preparation for the more numerous and more valuable articles which they are soon to receive.

The traces found on ancient rocks, as has been shown in the previous article, are those of animals, vegetables, and unorganized substances. The traces of animals are produced by quadrupeds, birds, lizards, turtles, frogs, mollusca, worms, crustacea, and zoophytes. These impressions are of various forms: some of them simple excavations; some lines, either straight or curved, and others complicated into various figures.

President Hitchcock has based his distinctions of fossil animal impressions on the following characters, viz.:—

1. Toes thick, pachydactylous; or thin, leptodactylous.

2. Feet winged.

3. Number of toes from two to five, inclusive.

4. Absolute and relative length of the toes.

5. Divarication of the lateral toes.

6. Angle made by the inner and middle, outer and middle toes.

7. Projection of the middle beyond the lateral toes.

8. Distance between tips of lateral toes.

9. Distance between tips of middle and inner and outer toes.

10. Position and direction of hind toe.

11. Character of claw.

12. Width of toes.

13. Number and length of phalangeal expansions.

14. Character of the heel.

15. Irregularities of under side of foot.

16. Versed sine of curvature of toes.

17. Angle of axis of foot with line of direction.

18. Distance of posterior part of the foot from line of direction.

19. Length of step.

20. Size of foot.

21. Character of the integuments of the foot.

22. Coprolites.

23. Means of distinguishing bipedal from quadrupedal tracks.

By these characters, President Hitchcock has distinguished physiological tracks, or those made by animated beings, into ten groups provisionally. To these may be added, "organic impressions," made by organized bodies; and the impressions made by inanimate bodies, called "physical impressions."

The specimens under our hands enable us to give some notion of the distinctions which characterize the greater part of these groups.