полная версия

полная версияThe Picturesque Antiquities of Spain

The month of June is likewise distinguished by the procession of the Corpus Christi. On this occasion all the principal streets are protected from the sun by canvas awnings; and from the windows of every house draperies are suspended, the materials of which are more or less rich according to the means of their respective proprietors. From an early hour of the morning, ushered in by sunshine and the gay orchestra of the Giralda bells, the vast marble pavement of the cathedral begins to disappear beneath the momentarily increasing crowd. Here all classes are mingled; but the most conspicuous are the arrivals from the surrounding villages, distinguished by their more sunburnt complexions and the showy colours of their costume, contrasted with the uniformly dark tints of the attire of the Sevillanos.

Here are seen also in great numbers, accompanied by their relatives, the gay cigarreras, whose acquaintance we shall presently make in the fabrica de tabaco. The instinctive coquetry discernible, no less in the studied reserve of their looks than in the smart step and faultless nicety of costume, indicates how easy would be the transition to the quality of the still more piquant but somewhat less moral maja. The black satin, low-quartered shoe is of a different material; but the snow-white stocking, and dark green skirt the same—and the black-velvet bordered mantilla is the identical one, which was held tight to the chin, when passing, the evening before, under the city walls on the return from the manufactory to the faubourg at the other extremity of Seville.

The procession, headed by a band of music, and accompanied by the dignitaries of the diocese, and civil authorities of the province, bearing cierges, winds through the principal streets, and re-enters the church to the sound of the two magnificent organs, never heard in unison except on this anniversary. The exterior of the principal portal is ornamented on this occasion with a sort of curtain, which is said to contain upwards of three thousand yards of crimson velvet, bordered with gold lace. The columns of the centre nave are also completely attired from top to bottom with coverings of the same material. The value of the velvet employed, is stated at nearly ten thousand pounds.

Christmas-day is also solemnized at Seville, with much zeal; but the manner of doing it honour presents more of novelty than splendour. At the early hour of seven the parish churches are completely filled. The organ pours forth, from that time until the termination of the service, an uninterrupted succession of airs, called seguidillas, from the dance to which they are adapted. On the gallery, which adjoins the organ-loft of each church, are established five or six muscular youths, selected for their untiring activity. They are provided each with a tambourine, and their duty consists in drawing from it as much, and as varied sound as it will render without coming to pieces. With this view they enter upon the amiable contest, and try, during three or four hours, which of their number, employing hands, knees, feet, and elbows in succession, can produce the most racking intonations. On the pavement immediately below, there is generally a group, composed of the friends of the performers, as may be discerned from the smiles of intelligence directed upwards and downwards. Some of these appear, from the animated signs of approbation and encouragement, with which they reward each more than usually violent concussion, to be backers of favourite heroes. During all this time one or two priests are engaged before the altar in the performance of a series of noiseless ceremonies; and the pavement of the body of the church is pressed by the knees of a dense crowd of devotees.

The propensity to robbery and assassination, attributed by several tourists to the population of this country, has been much exaggerated. The imagination of the stranger is usually so worked upon by these accounts, as to induce him never to set foot outside the walls of whatever city he inhabits, without being well armed. As far as regards the environs of Seville, this precaution is superfluous. They may be traversed in all directions, at all events within walking distance, or to the extent of a moderate ride, without risk. Far from exercising violence, the peasants never fail, in passing, to greet the stranger with a respectful salutation. But I cannot be guarantee for other towns or environs which I have not visited. It is certain that equal security does not exist nearer the coast, on the frequented roads which communicate between San Lucar, Xeres, and Cadiz; nor in the opposite direction, throughout the mountain passes of the Sierra Morena. But this state of things is far from being universal.

I would much prefer passing a night on a country road in the neighbourhood of Seville, to threading the maze of streets, which form the south-eastern portion of the town, mentioned above as containing the greater number of the residences of private families. This quarter is not without its perils. In fact, if dark deeds are practised, no situation could possibly be better suited to them. These Arab streets wind, and twist, and turn back on themselves like a serpent in pain. Every ten yards presents a hiding-place. There is just sufficient lighting up at night to prevent your distinguishing whether the street is clear or not: and the ground-floors of the houses, in the winter season, are universally deserted.

An effectual warning was afforded me, almost immediately on my arrival at Seville, against frequenting this portion of the town without precaution after nightfall. An acquaintance, a young Sevillano, who had been my daily companion during the first five or six days which followed my arrival, was in the habit of frequenting with assiduity, some of the above-mentioned streets. He inhabited one of them, and was continually drawn by potent attraction towards two others. In one, in particular, he followed a practice, the imprudence of which, in more than one respect, as he was much my junior, I had already pointed out to him. A lady, as you have already conjectured, resided in the house, in question. My friend, like many of his compatriots, "sighed to many;" but he loved this one; and she was precisely the one that "could ne'er be his." She allowed him, however, a harmless rendezvous, separated from all danger, as she thought, by the distance from the ground to the balcony, situated on the first-floor. The lady being married, and regular visiting being only possible at formal intervals, these interviews had by degrees alarmingly, as appeared to me, increased in frequency and duration; until at length during two hours each evening, my acquaintance poured forth in a subdued tone, calculated to reach only the fair form which bent over the balcony, his tender complaints.

The youth of these climes are communicative on subjects which so deeply interest their feelings; and whether willing or not, one is often admitted to share their secrets at the commencement of an acquaintance. It was thus that I had had an opportunity of lecturing my friend on the various dangers attending the practice in which he was persisting, and of recommending him—the best advice of all being, of course, useless—to revive the more prudent custom of by-gone times, and if he must offer nightly incense to the object of his fire, to adopt the mode sanctioned by Count Almaviva, and entrust his vows to the mercenary eloquence of choristers and catgut—to anything—or anybody, provided it be done by proxy. My warning was vain; but the mischief did not befall him exactly in the manner I had contemplated.

His cousin opened my door while I was breakfasting, and informed me that L– was in the house of Don G– A–, and in bed, having received a wound the previous night from some robbers; and that he wished to see me. I found him in a house, into which I had already been introduced, being one of those he most frequented. A bed had been prepared in the drawing-room, all the window-shutters of which were closed, and he was lying there, surrounded by the family of his host, to whom was added his sister. As he was unable to speak above a whisper, I was given the seat by the bedside, while he related to me his adventure.

He had just quitted the street of the balcony at about nine o'clock, and was approaching the house we were now in, when, on turning a corner, he was attacked by three ruffians, one of whom demanded his money in the usual terms, "Your purse, or your life!" while, before he had time to reply, but was endeavouring to pass on, a second faced him, and stabbed him in the breast through his cloak. He then ran forward, followed by the three, down the street, into the house, and up the staircase; the robbers not quitting the pursuit until he rang the bell on the first-floor. The surgeon had been immediately called, and had pronounced him wounded within—not an inch, but the tenth part of an inch—of his life; for the steel had penetrated to within that distance of his heart.

My first impression was that the robbers were acting a part, and had been hired to get rid of him,—otherwise what were the utility of stabbing him, when they might have rifled his pockets without such necessity? But this he assured me could not be the case, as the person most likely to fall under such suspicion, was incapable of employing similar means; adding, that that was the usual mode of committing robberies in Seville. I left him, after having assured him how much I envied his good fortune; seeing that he was in no danger, and only condemned to pass a week or two in the society of charming women, all zealously employed in nursing him—for such was the truth—one of the young ladies being supposed, and I fear with justice, to be the object of his addresses.

The ungrateful wretch convinced me by his reply (as we conversed in French, and were not understood by those present) that his greatest torment was impatience to escape from his confinement, in order to see or write to the other fair one.

At the end of a week he was sufficiently recovered to be removed to the house of his family. From certain hints, dropped during a conversation which took place more than a month after the event, it is to be feared that the knife of the assassin, in approaching so near to the heart of his intended victim, succeeded, by some mysterious electric transmission, in inflicting a positive wound on that of the lady of the balcony.

I afterwards learned that it was usual for those who inhabited or frequented this part of Seville, and indeed all other parts, excepting the few principal thoroughfares and streets containing the shops and cafés, to carry arms after nightfall; and in shaking hands with an acquaintance, I have sometimes perceived a naked sword-blade half visible among the folds of his cloak. These perils only exist in the winter, and not in all winters; only in those during which provisions increase in price beyond the average, and the season is more than usually rigorous: the poor being thus exposed to more than the accustomed privations.

There are towns in which assassination and robbery are marked by more audacity than is their habitual character in this part of Andalucia. Of these, Malaga is said to be one of the worst, although perhaps the most favoured spot in Europe, with respect to natural advantages. An instance of daring ruffianism occurred there this winter. A person of consideration in the town had been found in the street stabbed and robbed. His friends, being possessed of much influence, and disposing, no doubt, of other weighty inducements to action, the police was aroused to unusual activity; the murderer was arrested, and brought before the Alcalde primero. A summary mode of jurisprudence was put in practice, and the culprit was ordered for execution on the following day. On being led from the presence of the court, he turned to the Alcalde, and addressing him with vehemence, threatened him with certain death, in the event of the sentence being put in execution. The Alcalde, although doubtless not entirely free from anxiety, was, by the threat itself, the more forcibly bound to carry into effect the judgment he had pronounced. The execution, therefore, took place at the appointed hour. The following morning, the dead body of the Alcalde was found in a street adjoining that in which he resided.

LETTER XXII.

INQUISITION. COLLEGE OF SAN TELMO. CIGAR MANUFACTORY. BULL CIRCUS. EXCHANGE. AYUNTAMIENTO

Seville.In the faubourg of Triana, separated from the town by the river, may be distinguished remains of the ancient castle, which became the headquarters of the Inquisition, on its first creation, in 1482. That body was, however, shortly afterwards, compelled to evacuate the building, by a great inundation of the Guadalquivir, which occurred in the year 1626. It then moved into the town, and, from that period to the close of its functions, occupied an edifice situated in the parish of Saint Mark. Its jurisdiction did not extend beyond Andalucia. The entire body was composed of the following official persons:—three inquisitors, a judge of the fisc, a chief Alguazil, a receiver, (of fines,) five secretaries, ten counsellors, eighty qualifiers, one advocate of the fisc, one alcayde of the prison, one messenger, ten honest persons, two surgeons, and one porter. For the City of Seville, one hundred familiars: for the entire district, the commissaries, notaries, and familiars, amounted to four thousand. The ten honest persons cut but a sorry figure in so long a list. Do they not tempt you to parody Prince Hal's exclamation "Monstrous! but one halfpenny-worth of bread to this intolerable deal of sack?"

The Inquisition of Seville is of an earlier date than that of Toledo, and was the first established in Spain. It was likewise the most distinguished by the rigour of its sentences. The actual horrors of the inquisitorial vaults were, I imagine, in general much exaggerated. A few instances of severity, accompanied by a mystery, skilfully designed to magnify its effect, was sufficient to set on fire the inflammable imaginations of these sunny regions, and to spread universal terror. It was on finding these means insufficient for the extirpation of religious dissent, that, at length, executions were decreed by wholesale. Rather than give credit to the voluminous list of the secret cruelties, which were supposed by many to be exercised by the midnight tribunals, and which could have no adequate object, since a conversion brought about by such means could not, when known, profit the cause. I think it probable that all acts of severity were made as public as possible, in order to employ the terror they inspired as a means of swelling the ranks of Catholicism.

My opinion is in some measure backed by what occurred at Toledo. On the Inquisition of that city being dislodged from its palace,—now the seat of the provincial administration,—it was expected that the exploration of the subterraneous range of apartments, known to be extensive, would bring to light a whole Apocalypse of horrors; and all who had interest enough to obtain admission, pressed in crowds to be present at the opening. The disappointment was immense on finding not a single piece of iron, not the shadow of a skeleton, not a square inch of bloodstain. Each individual, however, during the permanence of these tribunals, lived in awe of their power; and the daily actions of thousands were influenced by the fear of becoming the victims of their cruelties, whether real or imaginary.

The terror which surrounded the persons of their agents invested them with a moral power, which frequently rendered them careless of the precaution of physical force in cases where it would have appeared to be a necessary instrument in the execution of their designs. This confidence was once well-nigh fatal to two zealous defenders of the faith. The Archbishop of Toledo, subsequently Cardinal Ximenes de Cisneros being on a visit at the residence of his brother of the see of Granada, it occurred to them during an after-dinner conversation that, could they accomplish the immediate conversion of the few thousands of Moors remaining in Granada, it would be the means of rendering a signal service to the Catholic Roman Apostolic religion.

Inflamed with a sudden ardour, and rendered doubly fearless of results by the excellence of the archiepiscopal repast, they resolved that the project should be put in execution that very evening.

Ever since the Conquest of Granada, a portion of the city had been appropriated to the Moors who thought proper to remain; and who received on that occasion the solemn assurance that no molestation would be offered to their persons or property, nor impediment thrown in the way of their worship. Their part of the town was called the Albaycin, and was separated from the rest by a valley. It contained some twenty to thirty thousand peaceably disposed inhabitants.

The two enterprising archbishops, their plan being matured (although insufficiently, as will appear) repaired to a house bordering on the Moorish quarter; and, calling together all the Familiars of the Inquisition who could be met with on the spur of the occasion, divided them into parties, each of a certain force, and dispatched them on their errand, which was, to enter the houses of the infidels, and to intimate to the principal families the behest of the prelates, requiring them by break of day, to abjure the errors of their creed, and to undergo the ceremony of baptism.

But in order that so meritorious a work should meet with the least possible delay, all the children under a certain age were to be conveyed instantaneously to the house occupied by the Archbishops, in order that they might be baptised at once.

The agents opened the campaign, and had already made away with a certain number of terrified infants, whose souls were destined to be saved thus unceremoniously, when the alarm began to spread; and, at the moment when the two dignitaries, impatient to commence operations, were inquiring for the first batch of unfledged heretics, an unexpected confusion of sounds was heard to proceed simultaneously from all sides of the house, and to increase rapidly in clearness and energy: and some of the attendants, entering, with alarm depicted on their countenances, announced that a few hundred armed Moors had surrounded the house, and were searching for an entrance.

It now, for the first time, occurred to the confederates, that difficulties might possibly attend the execution of their project; and their ardour having had nearly time to cool, Archbishop Ximenes, a personage by no means wanting in prudence and energy, during his moments of reason, employed the first instants of the siege in taking what precautions the circumstances admitted. He next proceeded to indite a hasty line, destined for the sovereigns Ferdinand and Isabella, who were journeying in the province, to inform them of his situation, and request immediate assistance. A black slave was selected to be the bearer of the letter: but, thinking to inspire him with greater promptitude and zeal, an attendant thrust into his hand a purse of money together with the document.

The effect of this was the opposite to that which was intended. The negro treated himself at every house of entertainment on his road; until, before he had half accomplished his journey, he was totally incapacitated for further progress. This circumstance could not, however, influence the fate of the besieged prelates; who would have had time to give complete satisfaction to the offended Moors before the King could receive the intelligence. Fortunately for them, the news had reached the governor of Granada, a general officer in whose religious zeal they had not had sufficient confidence to induce them to apply to him for aid in the emergency. That officer, on hearing the state of things, sent for a body of troops stationed at a neighbouring village, to whose commander he gave orders to place a guard, for the protection at the same time of the churchmen from violent treatment, and of the Moors from every sort of molestation. This adventure of the Archbishop drew upon him the temporary displeasure of the Court.

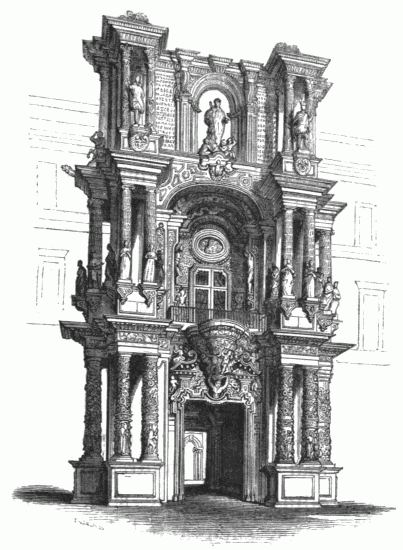

PORTAL OF SAN TELMO, SEVILLE.

The public buildings of Seville are on as grand a scale as those of some of the principal capitals of Europe. The college of San Telmo, fronting the Christina-gardens, is composed of two large quadrangles, behind a façade of five or six hundred feet in length, the centre of which is ornamented by a portal of very elaborate execution in the plateresco style. The architect, Matias de Figueroa, has literally crammed the three stories with carved columns, inscriptions, balconies, statues single and grouped, arches, medallions, wreaths, friezes. Without subjecting it to criticism on the score of purity, to which it makes no pretension, it certainly is rich in its general effect, and one of the best specimens of its style. This college was founded for the instruction of marine cadets, and for that reason named after S. Telmo, who is adopted by the mariners for their patron and advocate, as Santa Barbara is by the land artillery. He was a Dominican friar, and is recorded to have exercised miraculous influence on the elements, and thereby to have preserved the lives of a boatful of sailors, when on the point of destruction. The gardens in front of this building are situated between the river and the town walls. They are laid out in flower beds and walks. In the centre is a raised platform of granite, forming a long square of about an acre or more in extent, surrounded with a seat of white marble. It is entered at each end by an ascent of two or three steps. This is called the Salon, and on Sundays and Feast-days is the resort of the society of Seville. In the winter the hour of the promenade is from one to three o'clock; in the summer, the hours which intervene between sunset and supper. During winter as well as summer, the scent of the flowers of the surrounding gardens fills the Salon, than which it is difficult to imagine a more charming promenade.

The cigar manufactory is also situated outside the walls. It is a modern edifice of enormous dimensions, and not inelegant. In one of the rooms between two and three hundred cigareras, girls employed in rolling cigars, are seen at work, and heard likewise; for, such a Babel of voices never met mortal ear, although familiar with the music of the best furnished rookeries. The leaden roof, which covers the whole establishment, furnishes a promenade of several acres.

I am anxious to return to the interior of Seville, in order to introduce you to the Lonja; but we must not omit the Plaza de los Toros, (bull circus,) situated likewise outside the walls, and in view of the river. It is said to be the handsomest in Spain, as well as the largest. In fact it ought to be the best, as belonging to the principal city of the especial province of toreadores. It is approached by the gate nearest to the cathedral, and which deserves notice, being the handsomest gate of Seville. The principal entrance to the Plaza is on the opposite side from the town, where the building presents a large portion of a circle, ornamented with plain arches round the upper story. This upper portion extends only round a third part of the circus, which is the extent of the part completed with boxes and galleries, containing the higher class seats. All the remainder consists of an uniform series of retreating rows of seats, in the manner of an amphitheatre, sufficient for the accommodation of an immense multitude. These rows of seats are continued round the whole circus: but those beneath the upper building are not accessible to the same class of spectators as the others—the price of the place being different. This is regulated by the position with regard to the sun, the shaded seats being the dearest. The upper story consists of an elegant gallery, ornamented with a colonnade, in the centre of which the box of the president is surmounted by a handsomely decorated arch.

The circus, measured from the outside, is about two hundred and fifty feet in diameter. Those who are desirous of witnessing to what lengths human enthusiasm may be carried, should see a representation in this Plaza. With seven prime bulls from La Ronda, and a quadrille of Seville toreros—the enormous circumference as full as it can hold, (as it always is,) it is one of the most curious sights that can be met with.