полная версия

полная версияThe Picturesque Antiquities of Spain

I was at Valladolid during the regency of Espartero, when the cue given to these functionaries, relative to the surveillance of foreigners was very anti-French, and favourable to England. Now in the eyes of a gens-d'armes every one is a thief until he can bring proof to the contrary, just as by the jurisprudence of certain continental countries, every accused is presumed criminal—just as every one who comes to a Jew is presumed by him to have old clothes to sell, or money to borrow. Thus, owing to the nature of the duties of the Governor of Valladolid, every foreigner who met his eye, was a Frenchman, and an intrigant, until he should prove the reverse.

Not being aware of this at the time, I had drawn up my petition in French. On my return for the answer, my reception was any thing but encouraging. The excessive politeness of the Spaniard was totally lost sight of, and I perceived a moody-looking, motionless official, seated at a desk, with his hat resting on his eyebrows, and apparently studying a newspaper. I stood in the middle of the room for two or three minutes unnoticed; after which, deigning to lift his head, the personage inquired in a gruff tone, why I did not open my cloak. I was not as yet acquainted with the Spanish custom of drawing the end of the cloak from off the left shoulder, on entering a room. I therefore only half understood the question, and, being determined, at whatever price, to see San Pablo, I took off my cloak, laid it on a chair, and returned to face the official. "I took the liberty of requesting your permission to view the ancient monastery of San Pablo."—"And, pray, what is your reason for wishing to see San Pablo?"—"Curiosity."—"Oh, that is all, is it!"—"I own likewise, that, had I found that the interior corresponded, in point of architectural merit, with the façade, I might have presumed to wish to sketch it, and carry away the drawing in my portmanteau."—"Oh, no doubt—very great merit. You are a Frenchman?"—"I beg your pardon, only an Englishman."—"You! an Englishman!!" No answer. "And pray, from what part of England do you come?" I declined the county, parish, and house.

These English expressions, which I had expected would come upon his ear, with the same familiarity as if they had been Ethiopian or Chinese, produced a sudden revolution in my favour. The Solomon became immediately sensible of the extreme tact he had been displaying. Addressing me in perfect English, he proceeded to throw the blame of my brutal reception on the unfortunate state of his country. "All the French," he said, "who come here, come with the intention of intriguing and doing us harm. You wrote to me in French, and that was the cause of my error. The monastery is now a prison; I will give you an order to view it, but you will not find it an agreeable scene, it is full of criminals in chains." And he proceeded to prepare the order.

Not having recovered the compliment of being taken for a conspirator; nor admiring the civilisation of the governor of a province, who supposed that all the thirty-four millions of French, must be intrigants, I received his civilities in silence, took the order, and my departure. The most curious part of the affair was, that I had no passport at the time, having lost it on the road. Had my suspicious interrogator ascertained this before making the discovery that I was English, I should inevitably have been treated to more of San Pablo than I desired, or than would have been required for drawing it in detail.

The adjoining building is smaller, and with less pretension to magnificence is filled with details far more elaborate and curious. The Gothic architecture, like the Greek, assumed as a base and principle of decoration the imitation of the supposed primitive abodes of rudest invention. The Greek version of the idea is characterised by all the grace and finished elegance peculiar to its inventors; while the same principle in the hands of the framers of Gothic architecture, gave birth to a style less pure and less refined; but bolder, more true to its origin, and capable of more varied application. In both cases may be traced the imitation of the trunks of trees; but it is only in the Gothic style that the branches are added, and that instances are found of the representation of the knots and the bark. In this architecture, the caverns of the interior of mountains are evidently intended by the deep, multiplied, and diminishing arches, which form the entrances of cathedrals; and the rugged exterior of the rocky mass, which might enclose such a primæval abode, is imaged in the uneven and pinnacled walls.

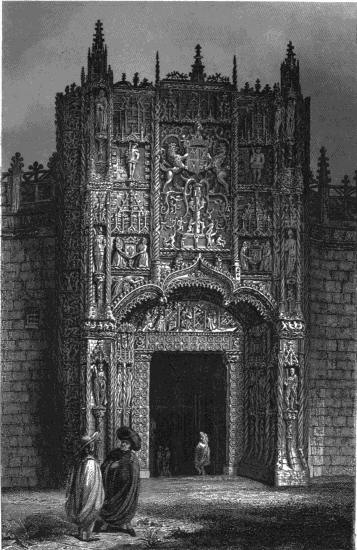

FAÇADE OF SAN GREGORIO, VALLADOLID.

The façade of the college of San Gregorio, adjoining San Pablo, furnishes an example of the Gothic decoration brought back to its starting point. The tree is here in its state of nature; and contributes its trunk, branches, leaves, and its handfuls of twigs bound together. A grove is represented, composed of strippling stems, the branches of some of which, united and bound together, curve over, and form a broad arch, which encloses the door-way. At each side is a row of hairy savages, each holding in one hand a club resting on the ground, and in the other an armorial shield. The intervals of the sculpture are covered with tracery, representing entwined twigs, like basket-work. Over the door is a stone fourteen feet long by three in height, covered with fleurs-de-lis on a ground of wicker-work, producing the effect of muslin. Immediately over the arch is a large flower-pot, in which is planted a pomegranate tree. Its branches spread on either side and bear fruit, besides a quantity of little Cupids, which cling to them in all directions. In the upper part they enclose a large armorial escutcheon, with lions for supporters. The arms are those of the founder of the college, Alonzo de Burgos, Bishop of Palencia. On either side of this design, and separated respectively by steins of slight trees, are compartments containing armed warriors in niches, and armorial shields. All the ornaments I have enumerated cover the façade up to its summit, along which project entwined branches and sticks, represented as broken off at different lengths.

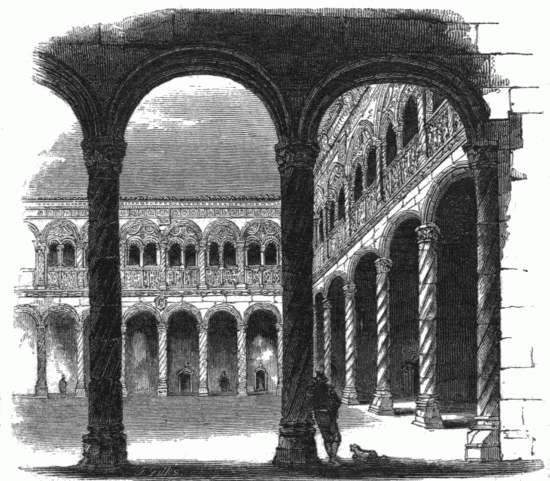

COURT OF SAN GREGORIO. VALLADOLID.

The court of this edifice is as elaborately ornamented as the façade, but it was executed at a much later period, and belongs to the renaissance. The pillars are extremely elegant and uncommon. The doorway of the library is well worthy of notice; also that of the refectory. The college of San Gregorio was, in its day, the most distinguished in Spain. Such was the reputation it had acquired, that the being announced as having studied there was a sufficient certificate for the proficiency of a professor in science and erudition. It is still a college, but no longer enjoys the same exclusive renown. In the centre of the chapel is the tomb of the founder, covered with excellent sculpture, representing the four virtues, and the figures of three saints and the Virgin. It is surrounded by a balustrade ornamented with elaborate carving. Berruguete is supposed to have been the sculptor, but in the uncertainty which exists on the subject, it would not be difficult to make a better guess, as it is very superior to all the works I have seen attributed to that artist. At the foot of the statue of the bishop is the following short inscription, "Operibus credite." To this prelate was due the façade of San Pablo; he was a Dominican monk at Burgos, where he founded several public works. He became confessor, chief chaplain, and preacher to Isabel the Catholic: afterwards Bishop of Cordova; and was ultimately translated to the see of Palencia. He received the sobriquet of Fray Mortero, as some say from the form of his face, added to the unpopularity which he shared with the two other favorites of Ferdinand and Isabella,—the Duke of Maqueda, and Cardinal Ximenes, with whom he figured in a popular triplet which at that period circulated throughout Spain,

Cardenas, el Cardenal,Con el padre Fray Mortero,Fraen el reyno al retortero.which may be freely translated thus:

What with his Grace the Cardinal,With Cardenas, and Father Mortar,—Spain calls aloud for quarter! quarter!The concise inscription seen on the tomb, was probably meant as an answer to this satire, and to the injurious opinion generally received respecting his character.

I returned from Toledo by way of Madrid and Saragoza. The diligence track from Toledo to Madrid was in a worse state than at the time of my arrival: a circumstance by no means surprising, since what with the wear and tear of carts and carriages, aided by that of the elements, and unopposed by human labour, it must deteriorate gradually until it becomes impassable. Since my last visit to the Museo the equestrian portrait of Charles the Fifth by Titian has been restored. It was in so degraded a condition that the lower half, containing the foreground and the horses' legs, presented scarcely a distinguishable object. It has been handled with care and talent, and, in its present position in the centre of the gallery, it now disputes the palm with the Spasimo, and is worth the journey to Madrid, were there nothing else to be seen there. I paid another visit to the Saint Elizabeth in the Academy, and to the Museum of Natural History, contained in the upper floor of the same building. This gallery boasts the possession of an unique curiosity; the entire skeleton of a Megatherion strides over the well-furnished tables of one of the largest rooms. I believe an idea of this gigantic animal can nowhere else be formed. The head must have measured about the dimensions of an elephant's body.

From Castile into Aragon the descent is continual, and the difference of climate is easily perceptible. Vineyards here climb the mountains, and the plains abound with olive-grounds, which are literally forests, and in which the plants attain to the growth of those of Andalucia. In corresponding proportion to the improving country, complaints are heard of its population. Murders and robberies form the subject of conversations; and certain towns are selected as more especially mal-composées, for the headquarters of strong bodies of guardia civile; without which precaution travelling would here be attended with no small peril. This state of things is attributed partly to the disorganising effects of the recent civil war, which raged with peculiar violence in this province. The same causes have operated less strongly in the adjoining Basque provinces, from their having to act on a population of a different character,—colder, more industrious, and more pacifically disposed, and without the desperate sternness and vindictive temper of the Aragonese.

The inhabitants of this province differ in costume and appearance from the rest of the Spaniards. Immediately on setting foot on the Aragonese territory, you are struck by the view of some peasant at the road-side: his black broad-brimmed hat,—waistcoat, breeches, and stockings all of the same hue, varied only by the broad faja, or sash of purple, make his tall erect figure almost pass for that of a Presbyterian clergyman, cultivating his Highland garden. The natives of Aragon have not the vivacity and polished talkativeness of the Andalucian and other Spaniards; they are reserved, slow, and less prompt to engage in conversation, and often abrupt and blunt in their replies. These qualities are not, however, carried so far as to silence the continual chatter of the interior of a Spanish diligence. Spanish travelling opens the sluices of communicativeness even of an Aragonese, as it would those of the denizens of a first class vehicle of a Great Western train, were they exposed during a short time to its vicissitudes.

However philosophers may explain the phenomenon, it is certain that the talkativeness of travellers augments in an inverse ratio to their comforts. The Spaniards complain of the silence of a French diligence; while, to a Frenchman, the occupants of the luxurious corners of an English railroad conveyance, must appear to be afflicted with dumbness.

Saragoza is one of the least attractive of Spanish towns. Its situation is as flat and uninteresting as its streets are ugly and monotonous. The ancient palace of the sovereigns of Aragon is now the Ayuntamiento. It would form, in the present day, but a sorry residence for a private individual, although it presents externally a massive and imposing aspect. Its interior is almost entirely sacrificed to an immense hall, called now the Lonja. It is a Gothic room, containing two rows of pillars, supporting a groined ceiling. It is used for numerous assemblies, elections, and sometimes for the carnival balls. The ancient Cathedral of La Seu is a gothic edifice, of great beauty internally; but the natives are still prouder of the more modern church called Nuestra Señora del Pilar,—an immense building in the Italian style, erected for the accommodation of a statue of the Virgin found on the spot, standing on a pillar. This image is the object of peculiar veneration.

After leaving Saragoza you are soon in the Basque provinces. The first considerable town is Tudela in Navarre; and here we were strongly impressed with the unbusinesslike nature of the Spaniard. This people, thoroughly good-natured and indefatigable in rendering a service, when the necessity arises for application to occupations of daily routine appear to exercise less intelligence than some other nations. It is probably owing to this cause that at Madrid the anterooms of the Foreign Office, situated in the palace, are, at four in the afternoon, the scene of much novelty and animation. In a town measuring no more than a mile and a half in each direction, the inexperienced stranger usually puts off to the last day of his stay the business of procuring his passport, and he is taken by surprise on finding it to be the most busy day of all. Little did he expect that the four or five visas will not be obtained in less than forty-eight hours: and he pays for his place in the diligence or mail (always paid in advance) several days before. It is consequently worth while to attend in person at the Secretary of State's office, in search of one's passport, in order to witness the scene.

The hour for the delivery of these inevitable documents, coincides with the shutting up for the day of all the embassies: so that those which require the subsequent visa of an ambassador, have to wait twenty-four hours. Hence the victims of official indifference, finding themselves disappointed of their departure, and minus the value of a place in the mail, give vent to their dissatisfaction in a variety of languages, forming a singular contrast to the phlegmatic and impassible porters and ushers, accustomed to the daily repetition of similar scenes. Some, rendered unjust by adversity, loudly accuse the government of complicity with the hotel-keepers. I saw a Frenchman whose case was cruel. His passport had been prepared at his embassy, and as he was only going to France, there were no more formalities necessary, but the visa of the police, and that of the foreign office. All was done but the last, and he was directed to call at four o'clock. His place was retained in that evening's mail, and being a mercantile traveller, both time and cash were of importance to him. On applying at the appointed hour, his passport was returned to him without the visa, because the French Secretary had, in a fit of absence, written Cadiz, instead of Bordeaux—he was to wait a day to get the mistake rectified.

These inconveniences were surpassed by that to which the passengers of our diligence were subjected at Tudela. Imagine yourself ensconced in a corner of the Exeter mail (when it existed) and on arriving at Taunton, or any intermediate town, being informed that an unforeseen circumstance rendered it necessary to remain there twenty-four hours, instead of proceeding in the usual manner. On this announcement being made at Tudela, I inquired what had happened, and learned that a diligence, which usually met ours, and the mules of which were to take us on, was detained a day at Tolosa, a hundred miles off. Rather than send a boy to the next stage to bring the team of mules, which had nothing to do, a dozen travellers had to wait until the better fortunes of the previous vehicle should restore it to its natural course.

As if this contretems was not sufficient, we were subjected to the most galling species of tyranny, weighing on the dearest of human privileges, I mean that which the proprietor of a shilling,—zwanziger, franc, or pezeta,—feels that he possesses of demanding to be fed. We had left Saragoza at nine in the morning, and had arrived without stoppages at six. A plentiful dinner, smoking on the table of the comedor, might have produced a temporary forgetfulness of our sorrows: but no entreaties could prevail on the hostess to lay the table-cloth. It was usual for the joint supper of the two coaches to take place at nine, and not an instant sooner should we eat. Weighed down by this complication of miseries, we sat, a disconsolate party, round the brasero, until at about eight our spirits began to rise at the sight of a table-cloth; and during half an hour, the occasional entrance of a waiting woman, with the different articles for the table, kept our hopes buoyed up, and our heads in motion towards the door, each time it opened to give entrance, now to a vinegar cruet, now to a salt-cellar.

At length an angelic figure actually bore in a large dish containing a quantity of vegetables, occasioning a cry of joy to re-echo through our end of the room. She placed it on a side-board and retired. Again the door opened, when to our utter dismay, another apparition moved towards the dish, took it up and carried it away; shutting the door carefully behind her. This was the best thing that could have occurred; since it produced a sudden outburst of mirth, which accompanied us to the table, now speedily adorned with the materials of a plentiful repast.

The next town to Tudela, is the gay and elegant little fortress of Pamplona, from which place an easy day's journey, through a tract of superb mountain scenery, brings you to Tolosa, the last resting-place on the Spanish side.

PART II

SEVILLE.

LETTER XV.

JOURNEY TO SEVILLE. CHARACTER OF THE SPANIARDS. VALLEY OF THE RHONE

Marseille.In order to reach the south of Spain, the longest route is that which, passing through France, leads by Bayonne to the centre of the northern frontier of the Peninsula, which it then traverses from end to end. It is not the longest in actual distance; but in regard to time, and to fatigue, and (for all who do not travel by Diligence), by far the longest, with regard to expense. Another route, longer, it is true, in distance, but shorter with respect to all these other considerations, is that by Lyons and Marseille; from either of which places, the journey may be made entirely by steam.

The shortest of all, and in every respect, is that by the Gibraltar mail, which leaves London and Falmouth once a week. This is a quicker journey than that through France, even for an inhabitant of France, supposing him resident at Paris, and to proceed to England viâ le Hâvre. But there is an objection to this route for a tourist. Desirous of visiting foreign scenes, he will find it too essentially an English journey—direct, sure, and horribly business-like and monotonous. You touch, it is true, at Lisbon, where during a few hours, you may escape from the beef and Stilton cheese, if not from the Port wine; and where you may enjoy the view of some fine scenery; but all the rest is straight-forward, desperate paddling night and day; with the additional objection, that being surrounded by English faces, living on English fare, and listening to English voices, the object of the traveller—that of quitting England—is not attained; since he cannot be said to have left that country, until he finds himself quarrelling with his rapacious boatman on the pier of the glittering Cadiz.

Although this arrangement may possess the merit of the magic transition from England to Andalucia, which, it must be allowed, is a great one—many will prefer being disembarked in France; looking forward, since there is a time for all things, to a still more welcome disembarkation on England's white shores, when the recollected vicissitudes of travel shall have disposed them to appreciate more than ever her comforts and civilization, and to be more forgiving to her defects; and, should they not be acquainted with the banks of the Rhone below Lyons, adopting that equally commodious and infinitely more varied course.

In fact, there are few who will not agree with me in pronouncing this the best way, for the tourist, of approaching Spain. It is not every one, who will not consider the gratifications which the inland territory of the Peninsula may offer to his curiosity too dearly purchased by the inconveniences inseparable from the journey. Add to this the superiority of the maritime provinces, with scarcely any exception, in point of climate, civilization, and attractions of every sort. Valencia, Barcelona, Malaga, and Cadiz are more agreeable places of residence, and possess more resources than even Madrid; but their chief advantage is a difference of climate almost incredible, from the limited distance which separates them from the centre of the Peninsula. The Andalucian coast enjoys one of the best climates in the world; while the Castiles, Aragon, and La Mancha can hardly be said to possess the average advantages in that respect; owing to the extremes of cold and heat, which characterize their summer and winter seasons, and which, during autumn and spring, are continually alternating in rapid transition.

Andalucia unites in a greater degree than the other maritime provinces, the advantages which constitute their superiority over the rest of Spain. It does more, for it presents to the stranger a combination of the principal features of interest, which render the Peninsula more especially attractive to the lover of travel. It is, in fact, to Spain what Paris is to France; Moscow and Petersburg to Russia. England, Italy, and Germany are not fit subjects for illustrating the comparison; their characteristic features of attraction and interest being disseminated more generally throughout all their provinces or states. Whoever wishes to find Spain herself, unalloyed, in her own character and costume, and in her best point of view, should disembark in Andalucia.

There, unlike the Castiles, and the still more northern provinces, in which only the earth and air remain Spanish, and those not the best Spanish—where all the picturesque and original qualities that distinguish the population, are fast fading away—the upper classes in their manners and costumes, and the Radicals in their politics, striving to become French—there, on the contrary, all is natural and national in its half-Arab nationality: and certainly nature and nationality have given proof of taste in selecting for their last refuge, the most delicious of regions; where earth and heaven have done their utmost to form an abode, worthy of the most beautiful of the human, as well as the brute creation.

I will not pause to inquire whether the reproach be justly addressed by the other Spaniards, to the inhabitants of this province, of indolence and love of pleasure, and of a disposition to deceitfulness, concealed beneath the gay courtesy of their manners; it would, indeed, be a surprising, a miraculous exception to the universal system of compensations that we recognise as governing the world, had not this people some prominent defect, or were they not exposed to some peculiar element of suffering, to counterbalance in a degree the especial and exclusive gifts heaped upon them. By what other means could their perfect happiness be interfered with? Let us, then, allow them their defects—the necessary shade in so brilliant a picture—defects which, in reducing their felicity to its due level, are easily fathomed, and their consequences guarded against, by sojourners amongst them, in whose eyes their peculiar graces, and the charm of their manner of life, find none the less favour from their being subject to the universal law of humanity. They cannot be better painted in a few words, than by the sketch, drawn by the witty and graceful Lantier, from the inhabitants of Miletus. "Les Milesiens," he says, "sont aimables. Ils emportent, peut-être, sur les Athéniens" (read "Castillans") "par leur politesse, leur aménité, et les agrémens de leur esprit. On leur reproche avec raison cette facilité—cette mollesse de mœurs, qui prend quelquefois l'air de la licence. Tout enchante les sens dans ce séjour fortuné—la pureté de l'air—la beauté des femmes—enfin leur musique—leurs danses, leurs jeux—tout inspire la volupté, et pénêtre l'âme d'une langueur délicieuse. Les Zéphirs ne s'y agitent que pour repandre au loin l'esprit des fleurs et des plantes, et embaumer l'air de leurs suaves odeurs."