полная версия

полная версияIsland Life; Or, The Phenomena and Causes of Insular Faunas and Floras

Discontinuous Specific Areas, why Rare.—But although discontinuous generic areas, or the separation from each other of species whose ancestors must once have occupied conterminous or overlapping areas, is of frequent occurrence, yet undoubted cases of discontinuous specific areas are very rare, except, as already stated, when one portion of a species inhabits an island. A few examples among mammalia have been referred to in our first chapter, but it may be said that these are examples of the very common phenomenon of a species being only found in the station for which its organisation adapts it; so that forest or marsh or mountain animals are of course only found where there are forests, marshes, or mountains. This may be true, and when the separate forests or mountains inhabited by the same species are not far apart there is little that needs explanation; but in one of the cases referred to there was a gap of a thousand miles between two of the areas occupied by the species, and this being too far for the animal to traverse through an uncongenial territory, we are forced to the conclusion that it must at some former period and under different conditions have occupied a considerable portion of the intervening area.

Among birds such cases of specific discontinuity are very rare and hardly ever quite satisfactory. This may be owing to birds being more rapidly influenced by changed conditions, so that when a species is divided the two portions almost always become modified into varieties or distinct species; while another reason may be that their powers of flight cause them to occupy on the average wider and less precisely defined areas than do the species of mammalia. It will be interesting therefore to examine the few cases on record, as we shall thereby obtain additional knowledge of the steps and processes by which the distribution of varieties and species has been brought about.

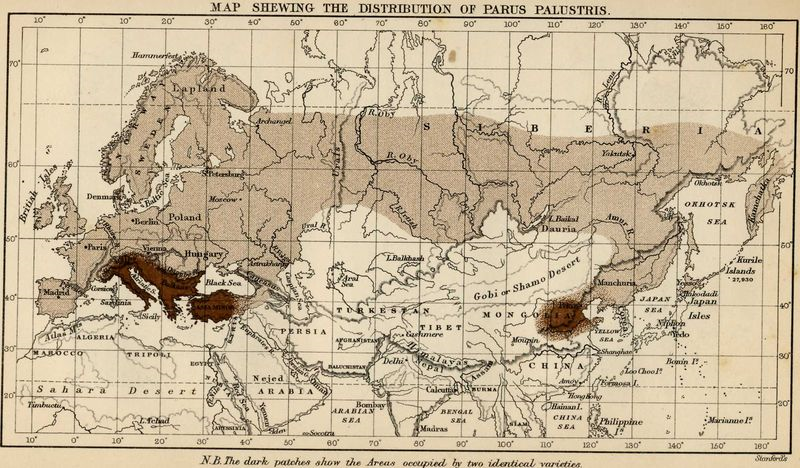

Discontinuity of the Area of Parus palustris.—Mr. Seebohm, who has travelled and collected in Europe, Siberia, and India, and possesses extensive and accurate knowledge of Palæarctic birds, has recently called attention to the varieties and sub-species of the marsh tit (Parus palustris), of which he has examined numerous specimens ranging from England to Japan.11 The curious point is that those of Southern Europe and of China are exactly alike, while all over Siberia a very distinct form occurs, forming the sub-species P. borealis.12 In Japan and Kamschatka other varieties are found, which have been named respectively P. japonicus and P. camschatkensis and another P. songarus in Turkestan and Mongolia. Now it all depends upon these forms being classed as sub-species or as true species whether this is or is not a case of discontinuous specific distribution. If Parus borealis is a distinct species from Parus palustris, as it is reckoned in Gray's Hand List of Birds, and also in Sharpe and Dresser's Birds of Europe, then Parus palustris has a most remarkable discontinuous distribution, as shown in the accompanying map, one portion of its area comprising Central and South Europe and Asia Minor, the other an undefined tract in Northern China, the two portions being thus situated in about the same latitude and having a very similar climate, but with a distance of about 4,000 miles between them. If, however, these two forms are reckoned as sub-species only, then the area of the species becomes continuous, while only one of its varieties or sub-species has a discontinuous area. It is a curious fact that P. palustris and P. borealis are found together in Southern Scandinavia and in some parts of Central Europe, and are said to differ somewhat in their note and their habits, as well as in colouration.

Discontinuity of Emberiza schœniclus.—The other case is that of our reed bunting (Emberiza schœniclus), which ranges over almost all Europe and Western Asia as far as the Yenesai valley and North-west India. It is then replaced by another smaller species, E. passerina, which ranges eastwards to the Lena river, and in winter as far south as Amoy in China; but in Japan the original species appears again, receiving a new name (E. pyrrhulina), but Mr. Seebohm assures us that it is quite indistinguishable from the European bird. Although the distance between these two portions of the species is not so great as in the last example, being about 2,000 miles, in other respects the case is an interesting one, because the forms which occupy the intervening space are recognised by Mr. Seebohm himself as undoubted species.13

The European and Japanese Jays.—Another case somewhat resembling that of the marsh tit is afforded by the European and Japanese jays (Garrulus glandarius and G. japonicus). Our common jay inhabits the whole of Europe except the extreme north, but is not known to extend anywhere into Asia, where it is represented by several quite distinct species. (See Map, Frontispiece.) But the great central island of Japan is inhabited by a jay (G. japonicus) which is very like ours, and was formerly classed as a sub-species only, in which case our jay would be considered to have a discontinuous distribution. But the specific distinctness of the Japanese bird is now universally admitted, and it is certainly a very remarkable fact that among the twelve species of jays which together range over all temperate Europe and Asia, one which is so closely allied to our English bird should be found at the remotest possible point from it. Looking at the map exhibiting the distribution of the several species, we can hardly avoid the conclusion that a bird very like our jay once occupied the whole area of the genus, that in various parts of Asia it became gradually modified into a variety of distinct species in the manner already explained, a remnant of the original type being preserved almost unchanged in Japan, owing probably to favourable conditions of climate and protection from competing forms.

Supposed Examples of Discontinuity among North American Birds.—In North America, the eastern and western provinces are so different in climate and vegetation, and are besides separated by such remarkable physical barriers—the arid central plains and the vast ranges of the Rocky Mountains and Sierra Nevada, that we can hardly expect to find species whose areas may be divided maintaining their identity. Towards the north however the above-named barriers disappear, the forests being almost continuous from east to west, while the mountain range is broken up by passes and valleys. It thus happens that most species of birds which inhabit both the eastern and western coasts of the North American continent have maintained their continuity towards the north, while even when differentiated into two or more allied species their areas are often conterminous or overlapping.

Almost the only bird that seems to have a really discontinuous range is the species of wren, Thryothorus bewickii, of which the type form ranges from the east coast to Kansas and Minnesota, while a longer-billed variety, T. bewickii spilurus, is found in the wooded parts of California and as far north as Puget Sound. If this really represents the range of the species there remains a gap of about 1,000 miles between its two disconnected areas. Other cases are those of Vireo bellii of the middle United States and the sub-species pusillus of California; and of the purple red-finch, Carpodacus purpureus, with its variety C. californicus; but unfortunately the exact limits of these varieties are in neither case known, and though each one is characteristic of its own province, it is possible that they may somewhere become conterminous, though in the case of the red-finches this does not seem likely to be the fact.

In a later chapter we shall have to point out some remarkable cases of this kind where one portion of the species inhabits an island; but the facts now given are sufficient to prove that the discontinuity of the area occupied by a single homogeneous species, by two varieties of a species, by two well-marked sub-species, and by two closely allied but distinct species, are all different phases of one phenomenon—the decay of ill-adapted, and their replacement by better-adapted forms, under the pressure of a change of conditions either physical or organic. We may now proceed with our sketch of the mode of distribution of higher groups.

Distribution and Antiquity of Families.—Just as genera are groups of allied species distinguished from all other groups by some well-marked structural characters, so families are groups of allied genera distinguished by more marked and more important characters, which are generally accompanied by a peculiar outward form and style of colouration, and by distinctive habits and mode of life. As a genus is usually more ancient than any of the species of which it is composed, because during its growth and development the original rudimentary species becomes supplanted by more and more perfectly adapted forms, so a family is usually older than its component genera, and during the long period of its life-history may have survived many and great terrestrial and organic changes. Many families of the higher animals have now an almost worldwide extension, or at least range over several continents; and it seems probable that all families which have survived long enough to develop a considerable variety of generic and specific forms have also at one time or other occupied an extensive area.

Discontinuity a Proof of Antiquity.—Discontinuity will therefore be an indication of antiquity, and the more widely the fragments are scattered the more ancient we may usually presume the parent group to be. A striking example is furnished by the strange reptilian fishes forming the order or sub-order Dipnoi, which includes the Lepidosiren and its allies. Only three or four living species are known, and these inhabit tropical rivers situated in the remotest continents. The Lepidosiren paradoxa is only known from the Amazon and some other South American rivers. An allied species, Lepidosiren annectens, sometimes placed in a distinct genus, inhabits the Gambia in West Africa, while the recent discovery in Eastern Australia of the Ceratodus or mud-fish of Queensland, adds another form to the same isolated group. Numerous fossil teeth, long known from the Triassic beds of this country, and also found in Germany and India in beds of the same age, agree so closely with those of the living Ceratodus that both are referred to the same genus. No more recent traces of any such animal have been discovered, but the Carboniferous Ctenodus and the Devonian Dipterus evidently belong to the same group, while in North America the Devonian rocks have yielded a gigantic allied form which has been named Heliodus by Professor Newberry. Thus an enormous range in time is accompanied by a very wide and scattered distribution of the existing species.

Whenever, therefore, we find two or more living genera belonging to the same family or order but not very closely allied to each other, we may be sure that they are the remnants of a once extensive group of genera; and if we find them now isolated in remote parts of the globe, the natural inference is that the family of which they are fragments once had an area embracing the countries in which they are found. Yet this simple and very obvious explanation has rarely been adopted by naturalists, who have instead imagined changes of land and sea to afford a direct passage from the one fragment to the other. If there were no cosmopolitan or very wide-spread families still existing, or even if such cases were rare, there would be some justification for such a proceeding; but as about one-fourth of the existing families of land mammalia have a range extending to at least three or four continents, while many which are now represented by disconnected genera are known to have occupied intervening lands or to have had an almost continuous distribution in tertiary times, all the presumptions are in favour of the former continuity of the group. We have also in many cases direct evidence that this former continuity was effected by means of existing continents, while in no single case has it been shown that such a continuity was impossible, and that it either was or must have been effected by means of continents now sunk beneath the ocean.

Concluding Remarks.—When writing on the subject of distribution it usually seems to have been forgotten that the theory of evolution absolutely necessitates the former existence of a whole series of extinct genera filling up the gap between the isolated genera which in many cases now alone exist; while it is almost an axiom of "natural selection" that such numerous forms of one type could only have been developed in a wide area and under varied conditions, implying a great lapse of time. In our succeeding chapters we shall show that the known and probable changes of sea and land, the known changes of climate, and the actual powers of dispersal of the different groups of animals, were such as would have enabled all the now disconnected groups to have once formed parts of a continuous series. Proofs of such former continuity are continually being obtained by the discovery of allied extinct forms in intervening lands, but the extreme imperfection of the geological record as regards land animals renders it unlikely that this proof will be forthcoming in the majority of cases. The notion that if such animals ever existed their remains would certainly be found, is a superstition which, notwithstanding the efforts of Lyell and Darwin, still largely prevails among naturalists; but until it is got rid of no true notions of the former distribution of life upon the earth can be attained.

CHAPTER V

THE POWERS OF DISPERSAL OF ANIMALS AND PLANTS

Statement of the general question of Dispersal—The Ocean as a Barrier to the Dispersal of Mammals—The Dispersal of Birds—The Dispersal of Reptiles—The Dispersal of Insects—The Dispersal of Land Mollusca—Great Antiquity of Land-shells—Causes favouring the Abundance of Land-shells—The Dispersal of Plants—Special adaptability of Seeds for Dispersal—Birds as agents in the Dispersal of Seeds—Ocean Currents as agents in Plant Dispersal—Dispersal along Mountain-chains—Antiquity of Plants as affecting their Distribution.

In order to understand the many curious anomalies we meet with in studying the distribution of animals and plants, and to be able to explain how it is that some species and genera have been able to spread widely over the globe, while others are confined to one hemisphere, to one continent, or even to a single mountain or a single island, we must make some inquiry into the different powers of dispersal of animals and plants, into the nature of the barriers that limit their migrations, and into the character of the geological or climatal changes which have favoured or checked such migrations.

The first portion of the subject—that which relates to the various modes by which organisms can pass over wide areas of sea and land—has been fully treated by Sir Charles Lyell, by Mr. Darwin, and many other writers, and it will only be necessary here to give a very brief notice of the best known facts on the subject, which will be further referred to when we come to discuss the particular cases that arise in regard to the faunas and floras of remote islands. But the other side of the question of dispersal—that which depends on geological and climatal changes—is in a far less satisfactory condition, for, though much has been written upon it, the most contradictory opinions still prevail, and at almost every step we find ourselves on the battle-field of opposing schools in geological or physical science. As, however, these questions lie at the very root of any general solution of the problems of distribution, I have given much time to a careful examination of the various theories that have been advanced, and the discussions to which they have given rise; and have arrived at some definite conclusions which I venture to hope may serve as the foundation for a better comprehension of these intricate problems. The four chapters which follow this are devoted to a full examination of these profoundly interesting and important questions, after which we shall enter upon our special inquiry—the nature and origin of insular faunas and floras.

The Ocean as a Barrier to the Dispersal of Mammals.—A wide extent of ocean forms an almost absolute barrier to the dispersal of all land animals, and of most of those which are aerial, since even birds cannot fly for thousands of miles without rest and without food, unless they are aquatic birds which can find both rest and food on the surface of the ocean. We may be sure, therefore, that without artificial help neither mammalia nor land birds can pass over very wide oceans. The exact width they can pass over is not determined, but we have a few facts to guide us. Contrary to the common notion, pigs can swim very well, and have been known to swim over five or six miles of sea, and the wide distribution of pigs in the islands of the Eastern Hemisphere may be due to this power. It is almost certain, however, that they would never voluntarily swim away from their native land, and if carried out to sea by a flood they would certainly endeavour to return to the shore. We cannot therefore believe that they would ever swim over fifty or a hundred miles of sea, and the same may be said of all the larger mammalia. Deer also swim well, but there is no reason to believe that they would venture out of sight of land. With the smaller, and especially with the arboreal mammalia, there is a much more effectual way of passing over the sea, by means of floating trees, or those floating islands which are often formed at the mouths of great rivers. Sir Charles Lyell describes such floating islands which were encountered among the Moluccas, on which trees and shrubs were growing on a stratum of soil which even formed a white beach round the margin of each raft. Among the Philippine Islands similar rafts with trees growing on them have been seen after hurricanes; and it is easy to understand how, if the sea were tolerably calm, such a raft might be carried along by a current, aided by the wind acting on the trees, till after a passage of several weeks it might arrive safely on the shores of some land hundreds of miles away from its starting-point. Such small animals as squirrels and field-mice might have been carried away on the trees which formed part of such a raft, and might thus colonise a new island; though, as it would require a pair of the same species to be thus conveyed at the same time, such accidents would no doubt be rare. Insects, however, and land-shells would almost certainly be abundant on such a raft or island, and in this way we may account for the wide dispersal of many species of both these groups.

Notwithstanding the occasional action of such causes, we cannot suppose that they have been effective in the dispersal of mammalia as a whole; and whenever we find that a considerable number of the mammals of two countries exhibit distinct marks of relationship, we may be sure that an actual land connection, or at all events an approach to within a very few miles of each other, has at one time existed. But a considerable number of identical mammalian families and even genera are actually found in all the great continents, and the present distribution of land upon the globe renders it easy to see how they have been able to disperse themselves so widely. All the great land masses radiate from the arctic regions as a common centre, the only break being at Behrings Strait, which is so shallow that a rise of less than a thousand feet would form a broad isthmus connecting Asia and America as far south as the parallel of 60° N. Continuity of land therefore may be said to exist already for all parts of the world (except Australia and a number of large islands, which will be considered separately), and we have thus no difficulty in the way of that former wide diffusion of many groups, which we maintain to be the only explanation of most anomalies of distribution other than such as may be connected with unsuitability of climate.

The Dispersal of Birds.—Wherever mammals can migrate other vertebrates can generally follow with even greater facility. Birds, having the power of flight, can pass over wide arms of the sea, or even over extensive oceans, when these are, as in the Pacific, studded with islands to serve as resting places. Even the smaller land-birds are often carried by violent gales of wind from Europe to the Azores, a distance of nearly a thousand miles, so that it becomes comparatively easy to explain the exceptional distribution of certain species of birds. Yet on the whole it is remarkable how closely the majority of birds follow the same laws of distribution as mammals, showing that they generally require either continuous land or an island-strewn sea as a means of dispersal to new homes.

The Dispersal of Reptiles.—Reptiles appear at first sight to be as much dependent on land for their dispersal as mammalia, but they possess two peculiarities which favour their occasional transmission across the sea—the one being their greater tenacity of life, the other their oviparous mode of reproduction. A large boa-constrictor was once floated to the island of St. Vincent, twisted round the trunk of a cedar tree, and was so little injured by its voyage that it captured some sheep before it was killed. The island is nearly two hundred miles from Trinidad and the coast of South America, whence the reptile almost certainly came.14 Snakes are, however, comparatively scarce on islands far from continents, but lizards are often abundant, and though these might also travel on floating trees, it seems more probable that there is some as yet unknown mode by which their eggs are safely, though perhaps very rarely, conveyed from island to island. Examples of their peculiar distribution will be given when we treat of the fauna of some islands in which they abound.

The Dispersal of Amphibia and Fresh-water Fishes.—The two lower groups of vertebrates, Amphibia and fresh-water fishes, possess special facilities for dispersal, in the fact of their eggs being deposited in water, and in their aquatic or semi-aquatic habits. They have another advantage over reptiles in being capable of flourishing in arctic regions, and in the power possessed by their eggs of being frozen without injury. They have thus, no doubt, been assisted in their dispersal by floating ice, and by that approximation of all the continents in high northern latitudes which has been the chief agent in producing the general uniformity in the animal productions of the globe. Some genera of Batrachia have almost a world-wide distribution; while the tailed Batrachia, such as the newts and salamanders, are almost entirely confined to the northern hemisphere, some of the genera spreading over the whole of the north temperate zone. Fresh-water fishes have often a very wide range, the same species being sometimes found in all the rivers of a continent. This is no doubt chiefly due to the want of permanence in river basins, especially in their lower portions, where streams belonging to distinct systems often approach each other and may be made to change their course from one to the other basin by very slight elevations or depressions of the land. Hurricanes and water-spouts also often carry considerable quantities of water from ponds and rivers, and thus disperse eggs and even small fishes. As a rule, however, the same species are not often found in countries separated by a considerable extent of sea, and in the tropics rarely the same genera. The exceptions are in the colder regions of the earth, where the transporting power of ice may have come into play. High ranges of mountains, if continuous for long distances, rarely have the same species of fish in the rivers on their two sides. Where exceptions occur, it is often due to the great antiquity of the group, which has survived so many changes in physical geography that it has been able, step by step, to reach countries which are separated by barriers impassable to more recent types. Yet another and more efficient explanation of the distribution of this group of animals is the fact that many families and genera inhabit both fresh and salt water; and there is reason to believe that many of the fishes now inhabiting the tropical rivers of both hemispheres have arisen from allied marine forms becoming gradually modified for a life in fresh water. By some of these various causes, or a combination of them, most of the facts in the distribution of fishes can be explained without much difficulty.