полная версия

полная версияIsland Life; Or, The Phenomena and Causes of Insular Faunas and Floras

There are about one hundred and fifty land birds known from the island of Madagascar, of which a hundred and twenty-seven are peculiar; and about half of these peculiar species belong to peculiar genera, many of which are extremely isolated, so that it is often difficult to class them in any of the recognised families, or to determine their affinities to any living birds.152 Among the other moiety, belonging to known genera, we find fifteen which have undoubted African affinities, while five or six are as decidedly Oriental, the genera or nearest allied species being found in India or the Malay Islands. It is on the presence of these peculiar Indian types that Dr. Hartlaub, in his recent work on the Birds of Madagascar and the Adjacent Islands, lays great stress, as proving the former existence of "Lemuria"; while he considers the absence of such peculiar African families as the plantain-eaters, glossy-starlings, ox-peckers, barbets, honey-guides, hornbills, and bustards—besides a host of peculiar African genera—as sufficiently disproving the statement in my Geographical Distribution of Animals that Madagascar is "more nearly related to the Ethiopian than to any other region," and that its fauna was evidently "mainly derived from Africa."

But the absence of the numerous peculiar groups of African birds is so exactly parallel to the same phenomenon among mammals, that we are justified in imputing it to the same cause, the more especially as some of the very groups that are wanting—the plantain-eaters and the trogons, for example,—are actually known to have inhabited Europe along with the large mammalia which subsequently migrated to Africa. As to the peculiarly Eastern genera—such as Copsychus and Hypsipetes, with a Dicrurus, a Ploceus, a Cisticola, and a Scops, all closely allied to Indian or Malayan species—although very striking to the ornithologist, they certainly do not outweigh the fourteen African genera found in Madagascar. Their presence may, moreover, be accounted for more satisfactorily than by means of an ancient Lemurian continent, which, even if granted, would not explain the very facts adduced in its support.

Let us first prove this latter statement.

The supposed "Lemuria" must have existed, if at all, at so remote a period that the higher animals did not then inhabit either Africa or Southern Asia, and it must have become partially or wholly submerged before they reached those countries; otherwise we should find in Madagascar many other animals besides Lemurs, Insectivora, and Viverridæ, especially such active arboreal creatures as monkeys and squirrels, such hardy grazers as deer or antelopes, or such wide-ranging carnivores as foxes or bears. This obliges us to date the disappearance of the hypothetical continent about the earlier part of the Miocene epoch at latest, for during the latter part of that period we know that such animals existed in abundance in every part of the great northern continents wherever we have found organic remains. But the Oriental birds in Madagascar, by whose presence Dr. Hartlaub upholds the theory of a Lemuria, are slightly modified forms of existing Indian genera, or sometimes, as Dr. Hartlaub himself points out, species hardly distinguishable from those of India. Now all the evidence at our command leads us to conclude that, even if these genera and species were in existence in the early Miocene period, they must have had a widely different distribution from what they have now. Along with so many African and Indian genera of mammals they then probably inhabited Europe, which at that epoch enjoyed a sub-tropical climate; and this is rendered almost certain by the discovery in the Miocene of France of fossil remains of trogons and jungle-fowl. If, then, these Indian birds date back to the very period during which alone Lemuria could have existed, that continent was quite unnecessary for their introduction into Madagascar, as they could have followed the same track as the mammalia of Miocene Europe and Asia; while if, as I maintain, they are of more recent date, then Lemuria had ceased to exist, and could not have been the means of their introduction.

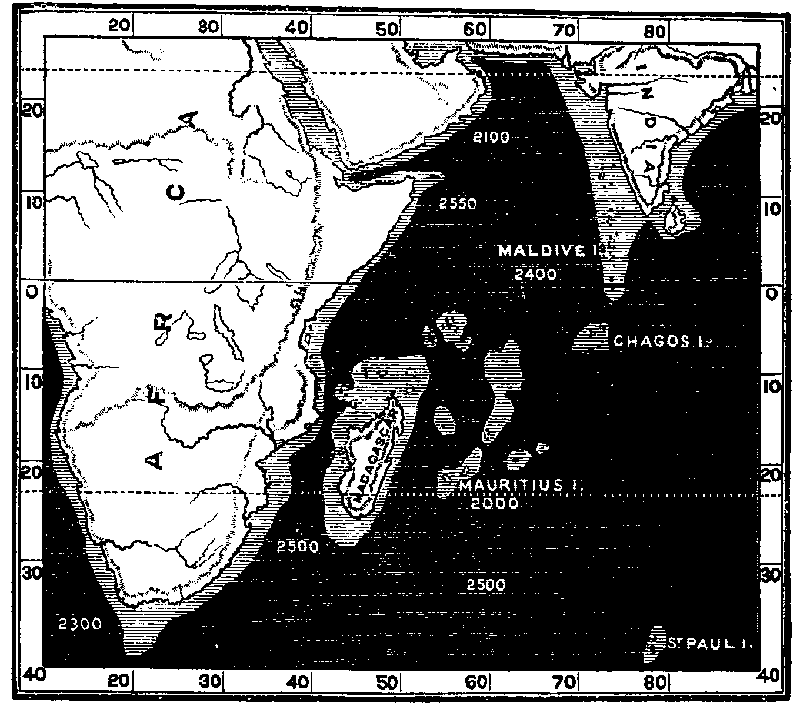

Submerged Islands between Madagascar and India.—Looking at the accompanying map of the Indian Ocean, we see that between Madagascar and India there are now extensive shoals and coral reefs, such as are usually held to indicate subsidence; and we may therefore fairly postulate the former existence here of several large islands, some of them not much inferior to Madagascar itself. These reefs are all separated from each other by very deep sea—much deeper than that which divides Madagascar from Africa, and we have therefore no reason to imagine their former union. But they would nevertheless greatly facilitate the introduction of Indian birds into the Mascarene Islands and Madagascar; and these facilities existing, such an immigration would be sure to take place, just as surely as American birds have entered the Galapagos and Juan Fernandez, as European birds now reach the Azores, and as Australian birds reach such a distant island as New Zealand. This would take place the more certainly because the Indian Ocean is a region of violent periodical storms at the changes of the monsoons, and we have seen in the case of the Azores and Bermuda how important a factor this is in determining the transport of birds across the ocean.

MAP OF THE INDIAN OCEAN.

Showing the position of banks less than 1,000 fathoms deep between Africa and the Indian Peninsula.

The final disappearance of these now sunken islands does not, in all probability, date back to a very remote epoch; and this exactly accords with the fact that some of the birds, as well as the fruit-bats of the genus Pteropus, are very closely allied to Indian species, if not actually identical, others being distinct species of the same genera. The fact that not one closely-allied species or even genus of Indian or Malayan mammals is found in Madagascar, sufficiently proves that it is no land-connection that has brought about this small infusion of Indian birds and bats; while we have sufficiently shown, that, when we go back to remote geological times no land-connection in this direction was necessary to explain the phenomena of the distribution of the Lemurs and Insectivora. A land-connection with some continent was undoubtedly necessary, or there would have been no mammalia at all in Madagascar; and the nature of its fauna on the whole, no less than the moderate depth of the intervening strait and the comparative approximation of the opposite shores, clearly indicate that the connection was with Africa.

Concluding Remarks on "Lemuria."—I have gone into this question in some detail, because Dr. Hartlaub's criticism on my views has been reproduced in a scientific periodical,153 and the supposed Lemurian continent is constantly referred to by quasi-scientific writers, as well as by naturalists and geologists, as if its existence had been demonstrated by facts, or as if it were absolutely necessary to postulate such a land in order to account for the entire series of phenomena connected with the Madagascar fauna, and especially with the distribution of the Lemuridæ.154 I think I have now shown, on the other hand, that it was essentially a provisional hypothesis, very useful in calling attention to a remarkable series of problems in geographical distribution, but not affording the true solution of those problems, any more than the hypothesis of an Atlantis solved the problems presented by the Atlantic Islands and the relations of the European and North American flora and fauna. The Atlantis is now rarely introduced seriously except by the absolutely unscientific, having received its death-blow by the chapter on Oceanic Islands in the Origin of Species, and the researches of Professor Asa Gray on the affinities of the North American and Asiatic floras. But "Lemuria" still keeps its place—a good example of the survival of a provisional hypothesis which offers what seems an easy solution of a difficult problem, and has received an appropriate and easily remembered name, long after it has been proved to be untenable.

It is now more than fifteen years since I first showed, by a careful examination of all the facts to be accounted for, that the hypothesis of a Lemurian continent was alike unnecessary to explain one portion of the facts, and inadequate to explain the remaining portion.155 Since that time I have seen no attempt even to discuss the question on general grounds in opposition to my views, nor on the other hand have those who have hitherto supported the hypothesis taken any opportunity of acknowledging its weakness and inutility. I have therefore here explained my reasons for rejecting it somewhat more fully and in a more popular form, in the hope that a check may thus be placed on the continued re-statement of this unsound theory as if it were one of the accepted conclusions of modern science.

The Mascarene Islands. 156—In the Geographical Distribution of Animals, a summary is given of all that was known of the zoology of the various islands near Madagascar, which to some extent partake of its peculiarities, and with it form the Malagasy sub-region of the Ethiopian region. As no great additions have since been made to our knowledge of the fauna of these islands, and my object in this volume being more especially to illustrate the mode of solving distributional problems by means of the most suitable examples, I shall now confine myself to pointing out how far the facts presented by these outlying islands support the views already enunciated with regard to the origin of the Madagascar fauna.

The Comoro Islands.—This group of islands is situated nearly midway between the northern extremity of Madagascar and the coast of Africa. The four chief islands vary between sixteen and forty miles in length, the largest being 180 miles from the coast of Africa, while one or two smaller islets are less than 100 miles from Madagascar. All are volcanic, Great Comoro being an active volcano 8,500 feet high; and, as already stated, they are situated on a submarine bank with less than 500 fathoms soundings, connecting Madagascar with Africa. There is reason to believe, however, that these islands are of comparatively recent origin, and that the bank has been formed by matter ejected by the volcanoes or by upheaval. Anyhow, there is no indication whatever of there having been here a land-connection between Madagascar and Africa; while the islands themselves have been mainly colonised from Madagascar, some of them making a near approach to the 100-fathom bank which surrounds that island.

The Comoros contain two land mammals, a lemur and a civet, both of Madagascar genera and the latter an identical species, and there is also a peculiar species of fruit-bat (Pteropus comorensis), a group which ranges from Australia to Asia and Madagascar but is unknown in Africa. Of land-birds forty-one species are known, of which sixteen are peculiar to the islands, twenty-one are found also in Madagascar, and three found in Africa and not in Madagascar; while of the peculiar species, six belong to Madagascar or Mascarene genera. A species of Chameleon is also peculiar to the islands.

These facts point to the conclusion that the Comoro Islands have been formerly more nearly connected with Madagascar than they are now, probably by means of intervening islets and the former extension of the latter island to the westward, as indicated by the extensive shallow bank at its northern extremity, so as to allow of the easy passage of birds, and the occasional transmission of small mammalia by means of floating trees.157

The Seychelles Archipelago.—This interesting group consists of about thirty small islands situated 700 miles N.N.E. of Madagascar, or almost exactly in the line formed by continuing the central ridge of that great island. The Seychelles stand upon a rather extensive shallow bank, the 100-fathom line around them enclosing an area nearly 200 miles long by 100 miles wide, while the 500-fathom line shows an extension of nearly 100 miles in a southern direction. All the larger islands are of granite, with mountains rising to 3,000 feet in Mahé, and to from 1,000 to 2,000 feet in several of the other islands. We can therefore hardly doubt that they form a portion of the great line of upheaval which produced the central granitic mass of Madagascar, intervening points being indicated by the Amirantes, the Providence, and the Farquhar Islands, which, though all coralline, probably rest on a granitic basis. Deep channels of more than 1,000 fathoms now separate these islands from each other, and if they were ever sufficiently elevated to be united, it was probably at a very remote epoch.

The Seychelles may thus have had ample facilities for receiving from Madagascar such immigrants as can pass over narrow seas; and, on the other hand, they were equally favourably situated as regards the extensive Saya de Malha and Cargados banks, which were probably once large islands, and may have supported a rich insular flora and fauna of mixed Mascarene and Indian type. The existing fauna and flora of the Seychelles must therefore be looked upon as the remnants which have survived the partial submergence of a very extensive island; and the entire absence of non-aërial mammalia may be due, either to this island having never been actually united to Madagascar, or to its having since undergone so much submergence as to have led to the extinction of such mammals as may once have inhabited it. The birds and reptiles, however, though few in number, are very interesting, and throw some further light on the past history of the Seychelles.

Birds of the Seychelles.—Fifteen indigenous land-birds are known to inhabit the group, thirteen of which are peculiar species,158 belonging to genera which occur also in Madagascar or Africa. The genera which are more peculiarly Indian are,—Copsychus and Hypsipetes, also found in Madagascar; and Palæornis, which has species in Mauritius and Rodriguez, as well as one on the continent of Africa. A black parrot (Coracopsis), congeneric with two species that inhabit Madagascar and with one that is peculiar to the Comoros; and a beautiful red-headed blue pigeon (Alectorænas pulcherrimus) allied to those of Madagascar and Mauritius, but very distinct, are the most remarkable species characteristic of this group of islands.

Reptiles and Amphibia of the Seychelles.—The reptiles and amphibia are rather numerous and very interesting, indicating clearly that the islands can hardly be classed as oceanic. There are seven species of lizards, three being peculiar to the islands, while the others have rather a wide range. The first is a chameleon—defenceless slow-moving lizards, especially abundant in Madagascar, from which no less than eighteen species are now known, about the same number as on the continent of Africa. The Seychelles species (Chamæleon tigris) also occurs at Zanzibar. The next are skinks (Scincidæ), small ground-lizards with a wide distribution in the Eastern hemisphere. Two species are however peculiar to the islands—Mabuia seychellensis and M. wrightii. The other peculiar species is one of the geckoes (Geckotidæ) named Æluronyx seychellensis, and there are also three other geckoes, Phelsuma madagascarensis, Gehyra mutilata and Hemidactylus frenatus, the two latter having a wide distribution in the tropical regions of both hemispheres. These lizards, clinging as they do to trees and timber, are exceedingly liable to be carried in ships from one country to another, and I am told by Dr. Günther that some are found almost every year in the London Docks. It is therefore probable, that when species of this family have a very wide range they have been assisted in their migrations by man, though their habit of clinging to trees also renders them likely to be floated with large pieces of timber to considerable distances. Dr. Percival Wright, to whom I am indebted for much information on the productions of the Seychelles Archipelago, informs me that the last-named species varies greatly in colour in the different islands, so that he could always tell from which particular island a specimen had been brought. This is analogous to the curious fact of certain lizards on the small islands in the Mediterranean being always very different in colour from those of the mainland, usually becoming rich blue or black (see Nature, Vol. XIX. p. 97); and we thus learn how readily in some cases differences of colour are brought about, either directly or indirectly, by local conditions.

Snakes, as is usually the case in small or remote islands, are far less numerous than lizards, only two species being known. One, Dromicus seychellensis, is a peculiar species of the family Colubridæ, the rest of the genus being found in Madagascar and South America. The other, Boodon geometricus, one of the Lycodontidæ, or fanged ground-snakes, is also peculiar. So far, then, as the reptiles are concerned, there is nothing but what is easily explicable by what we know of the general means of distribution of these animals.

We now come to the Amphibia, which are represented in the Seychelles by two tailless and two serpent-like forms. The frogs are Rana mascareniensis, found also in Mauritius, Bourbon, Angola, and Abyssinia, and probably all over tropical Africa; and Megalixalus seychellensis a peculiar tree-frog having allies in Madagascar and tropical Africa. It is found, Dr. Wright informs me, on the Pandani or screw-pines; and as these form a very characteristic portion of the vegetation of the Mascarene Islands, all the species being peculiar and confined each to a single island or small group, we may perhaps consider it as a relic of the indigenous fauna of that more extensive land of which the present islands are the remains.

The serpentine Amphibia are represented by two species of Cæcilia. These creatures externally resemble large worms, except that they have a true head with jaws and rudimentary eyes, while internally they have of course a true vertebrate skeleton. They live underground, burrowing by means of the ring-like folds of the skin which simulate the jointed segments of a worm's body, and when caught they exude a viscid slime. The young have external gills which are afterwards replaced by true lungs, and this peculiar metamorphosis shows that they belong to the amphibia rather than to the reptiles. The Cæcilias are widely but very sparingly distributed through all the tropical regions; a fact which may, as we have seen, be taken as an indication of the great antiquity of the group, and that it is now verging towards extinction. In the Seychelles Islands there appear to be three species of these singular animals. Cryptopsophis multiplicatus is confined to the islands; Herpele squalostoma is found also in Western India and in Africa; while Hypogeophis rostratus inhabits both West Africa and South America.159 This last is certainly one of the most remarkable cases of the wide and discontinuous distribution of a species; and when we consider the habits of life of these animals and the extreme slowness with which it is likely they can migrate into new areas, we can hardly arrive at any other conclusion than that this species once had an almost world-wide range, and that in the process of dying out it has been left stranded, as it were, in these three remote portions of the globe. The extreme stability and long persistence of specific form which this implies is extraordinary, but not unprecedented, among the lower vertebrates. The crocodiles of the Eocene period differ but slightly from those of the present day, while a small freshwater turtle from the Pliocene deposits of the Siwalik Hills is absolutely identical with a still living Indian species, Emys tectus. The mud-fish of Australia, Ceratodus forsteri is a very ancient type, and may well have remained specifically unchanged since early Tertiary times. It is not, therefore, incredible that this Seychelles Cæcilia may be the oldest land vertebrate now living on the globe; dating back to the early part of the Tertiary period, when the warm climate of the northern hemisphere in high latitudes and the union of the Asiatic and American continents allowed of the migration of such types over the whole northern hemisphere, from which they subsequently passed into the southern hemisphere, maintaining themselves only in certain limited areas, where the physical conditions were especially favourable, or where they were saved from the attacks of enemies or the competition of higher forms.

Fresh-water Fishes.—The only other vertebrates in the Seychelles are two fresh-water fishes abounding in the streams and rivulets. One, Haplochilus playfairii is peculiar to the islands, but there are allied species in Madagascar. It is a pretty little fish about four inches long, of an olive colour, with rows of red spots, and is very abundant in some of the mountain streams. The fishes of this genus, as I am informed by Dr. Günther, often inhabit both sea and fresh water, so that their migration from Madagascar to the Seychelles and subsequent modification, offers no difficulty. The other species is Fundulus orthonotus, found also on the east coast of Africa; and as both belong to the same family—Cyprinodontidæ—this may possibly have migrated in a similar manner.

Land-shells.—The only other group of animals inhabiting the Seychelles which we know with any approach to completeness, are the land and fresh-water mollusca, but they do not furnish any facts of special interest. About forty species are known, and Mr. Geoffrey Nevill, who has studied them, thinks their meagre number is chiefly owing to the destruction of so much of the forests which once covered the islands. Seven of the species—and among them one of the most conspicuous, Achatina fulica—have almost certainly been introduced; and the remainder show a mixture of Madagascar and Indian forms, with a preponderance of the latter. Five genera—Streptaxis, Cyathoponea, Onchidium, Helicina and Paludomus, are mentioned as being especially Indian, while only two—Tropidophora and Gibbus, are found in Madagascar but not in India.160 About two-thirds of the species appear to be peculiar to the islands.

Mauritius, Bourbon and Rodriguez.—These three islands are somewhat out of place in this chapter, because they really belong to the oceanic group, being of volcanic formation, surrounded by deep sea, and possessing no indigenous mammals or amphibia. Yet their productions are so closely related to those of Madagascar, to which they may be considered as attendant satellites, that it is absolutely necessary to associate them together if we wish to comprehend and explain their many interesting features.

Mauritius and Bourbon are lofty volcanic islands, evidently of great antiquity. They are about 100 miles apart, and the sea between them is less than 1,000 fathoms deep, while on each side it sinks rapidly to depths of 2,400 and 2,600 fathoms. We have therefore no reason to believe that they have ever been connected with Madagascar, and this view is strongly supported by the character of their indigenous fauna. Of this, however, we have not a very complete or accurate knowledge, for though both islands have long been occupied by Europeans, the study of their natural products was for a long time greatly neglected, and owing to the rapid spread of sugar cultivation, the virgin forests, and with them no doubt many native animals, have been almost wholly destroyed. There is, however, no good evidence of there ever having been any indigenous mammals or amphibia, though both are now found and are often recorded among the native animals.161

The smaller and more remote island, Rodriguez, is also volcanic; but it has, besides a good deal of coralline rock, an indication of partial submergence helping to account for the poverty of its fauna and flora. It stands on a 100-fathom bank of considerable extent, but beyond this the sea rapidly deepens to more than 2,000 fathoms, so that it is truly oceanic like its larger sister isles.

Birds.—The living birds of these islands are few in number and consist mainly of peculiar species of Mascarene types, together with two peculiar genera—Oxynotus belonging to the Campephagidæ or caterpillar-catchers, a family abundant in the old-world tropics; and a dove, Trocazza, forming a peculiar sub-genus. The origin of these birds offers no difficulty, looking at the position of the islands and of the surrounding shoals and islets.