полная версия

полная версияIsland Life; Or, The Phenomena and Causes of Insular Faunas and Floras

A good example of isolated species of a group nearer home, is afforded by the snow-partridges of the genus Tetraogallus. One species inhabits the Caucasus range and nowhere else, keeping to the higher slopes from 6,000 to 11,000 feet above the sea, and accompanying the ibex in its wanderings, as both feed on the same plants. Another has a wider range in Asia Minor and Persia, from the Taurus mountains to the South-east corner of the Caspian Sea; a third species inhabits the Western Himalayas, between the forests and perpetual snow, extending eastwards to Nepal; while a fourth is found on the north side of the mountains in Thibet, and the ranges of these two perhaps overlap; the last species inhabit the Altai mountains, and like the two first appears to be completely separated from all its allies.

There are some few still more extraordinary cases in which the species of one genus are separated in remote continents or islands. The most striking of these is that of the tapirs, forming the genus Tapirus, of which there are two or three species in South America, and one very distinct species in Malacca and Borneo, separated by nearly half the circumference of the globe. Another example among quadrupeds is a peculiar genus of moles named Urotrichus, of which one species inhabits Japan and the other British Columbia. The cuckoo-like honey-guides, forming the genus Indicator, are tolerably abundant in tropical Africa, but there are two outlying species, one in the Eastern Himalaya mountains, the other in Borneo, both very rare, and recently an allied species has been found in the Malay peninsula. The beautiful blue and green thrush-tits forming the genus Cochoa, have two species in the Eastern Himalayas and Eastern China, while the third is confined to Java; the curious genus Eupetes, supposed to be allied to the dippers, has one species in Sumatra and Malacca, while four other species are found two thousand miles distant in New Guinea; lastly, the lovely ground-thrushes of the genus Pitta, range from Hindostan to Australia, while a single species, far removed from all its near allies, inhabits West Africa.

Peculiarities of Generic, and Family Distribution.—The examples now given sufficiently illustrate the mode in which the several species of a genus are distributed. We have next to consider genera as the component parts of families, and families of orders, from the same point of view.

All the phenomena presented by the species of a genus are reproduced by the genera of a family, and often in a more marked degree. Owing, however, to the extreme restriction of genera by modern naturalists, there are not many among the higher animals that have a world-wide distribution. Among the mammalia there is no such thing as a truly cosmopolitan genus. This is owing to the absence of all the higher orders except the mice from Australia, while the genus Mus, which occurs there, is represented by a distinct group, Hesperomys, in America. If, however, we consider the Australian dingo as a native animal we might class the genus Canis as cosmopolite, but the wild dogs of South America are now formed into separate genera by some naturalists. Many genera, however, range over three or more continents, as Felis (the cat genus) absent only from Australia; Ursus (the bear genus) absent from Australia and tropical Africa; Cervus (the deer genus) with nearly the same range; and Sciurus (the squirrel genus) found in all the continents but Australia. Among birds Turdus, the thrush, and Hirundo, the swallow genus, are the only perching birds which are truly cosmopolites; but there are many genera of hawks, owls, wading and swimming birds, which have a world-wide range.

As a great many genera consist of single species there is no lack of cases of great restriction, such as the curious lemur called the "potto," which is found only at Sierra Leone, and forms the genus Perodicticus; the true chinchillas found only in the Andes of Peru and Chili south of 9° S. lat. and between 8,000 and 12,000 feet elevation; several genera of finches each confined to limited portions of the higher Himalayas, the blood-pheasants (Ithaginis) found only above 10,000 feet from Nepal to East Thibet; the bald-headed starling of the Philippine islands, the lyre-birds of East Australia, and a host of others.

It is among the different genera of the same family that we meet with the most striking examples of discontinuity, although these genera are often as unmistakably allied as are the species of a genus; and it is these cases that furnish the most interesting problems to the student of distribution. We must therefore consider them somewhat more fully.

Among mammalia the most remarkable of these divided families is that of the camels, of which one genus Camelus, the true camels, comprising the camel and dromedary, is confined to Asia, while the other Auchenia, comprising the llamas and alpacas, is found only in the high Andes and in the plains of temperate South America. Not only are these two genera separated by the Atlantic and by the greater part of the land of two continents, but one is confined to the Northern and the other to the Southern hemisphere. The next case, though not so well known, is equally remarkable; it is that of the Centetidæ, a family of small insectivorous animals, which are wholly confined to Madagascar and the large West Indian islands Cuba and Hayti, the former containing five genera and the latter a single genus with a species in each island. Here again we have the whole continent of Africa as well as the Atlantic ocean separating allied genera. Two families (or subfamilies) of rat-like animals, Octodontidæ and Echimyidæ, are also divided by the Atlantic. Both are mainly South American, but the former has two genera in North and East Africa, and the latter also two in South and West Africa. Two other families of mammalia, though confined to the Eastern hemisphere, are yet markedly discontinuous. The Tragulidæ are small deer-like animals, known as chevrotains or mouse-deer, abundant in India and the larger Malay islands and forming the genus Tragulus; while another genus, Hyomoschus, is confined to West Africa. The other family is the Simiidæ or anthropoid apes, in which we have the gorilla and chimpanzee confined to West and Central Africa, while the allied orangs are found only in the islands of Sumatra and Borneo, the two groups being separated by a greater space than the Echimyidæ and other rodents of Africa and South America.

Among birds and reptiles we have several families, which, from being found only within the tropics of Asia, Africa, and America, have been termed tropicopolitan groups. The Megalæmidæ or barbets are gaily coloured fruit-eating birds, almost equally abundant in tropical Asia and Africa, but less plentiful in America, where they probably suffer from the competition of the larger sized toucans. The genera of each country are distinct, but all are closely allied, the family being a very natural one. The trogons form a family of very gorgeously coloured and remarkable insect-eating birds very abundant in tropical America, less so in Asia, and with a single genus of two species in Africa.

Among reptiles we have two families of snakes—the Dendrophidæ or tree-snakes, and the Dryiophidæ or green whip-snakes—which are also found in the three tropical regions of Asia, Africa, and America, but in these cases even some of the genera are common to Asia and Africa, or to Africa and America. The lizards forming the family Amphisbænidæ are divided between tropical Africa and America, a few species only occurring in the southern portion of the adjacent temperate regions; while even the peculiarly American family of the iguanas is represented by two genera in Madagascar, and one in the Fiji and Friendly Islands. Passing on to the Amphibians the worm-like Cæciliadæ are tropicopolitan, as are also the toads of the family Engystomatidæ. Insects also furnish some analogous cases, three genera of Cicindelidæ, (Pogonostoma, Ctenostoma, and Peridexia) showing a decided connection between this family in South America and Madagascar; while the beautiful family of diurnal moths, Uraniidæ, is confined to the same two countries. A somewhat similar but better known illustration is afforded by the two genera of ostriches, one confined to Africa and Arabia, the other to the plains of temperate South America.

General features of Overlapping and Discontinuous Areas.—These numerous examples of discontinuous genera and families form an important section of the facts of animal dispersal which any true theory must satisfactorily account for. In greater or less prominence they are to be found all over the world, and in every group of animals, and they grade imperceptibly into those cases of conterminous and overlapping areas which we have seen to prevail in most extensive groups of species, and which are perhaps even more common in those large families which consist of many closely allied genera. A sufficient proof of the overlapping of generic areas is the occurrence of a number of genera of the same family together. Thus in France or Italy about twenty genera of warblers (Sylviadæ) are found, and as each of the thirty-three genera of this family inhabiting temperate Europe and Asia has a different area, a great number must here overlap. So, in most parts of Africa, at least ten or twelve genera of antelopes may be found, and in South America a large proportion of the genera of monkeys of the family Cebidæ occur in many districts; and still more is this the case with the larger bird families, such as the tanagers, the tyrant shrikes, or the tree-creepers, so that there is in all these extensive families no genus whose area does not overlap that of many others. Then among the moderately extensive families we find a few instances of one or two genera isolated from the rest, as the spectacled bear, Tremarctos, found only in Chili, while the remainder of the family extends from Europe and Asia over North America to the Mountains of Mexico, but no further south; the Bovidæ, or hollow-horned ruminants, which have a few isolated genera in the Rocky Mountains and the islands of Sumatra and Celebes; and from these we pass on to the cases of wide separation already given.

Restricted Areas of Families.—As families sometimes consist of single genera and even single species, they often present examples of very restricted range; but what is perhaps more interesting are those cases in which a family contains numerous species and sometimes even several genera, and yet is confined to a narrow area. Such are the golden moles (Chrysochloridæ) consisting of two genera and three species, confined to extratropical South Africa; the hill-tits (Liotrichidæ), a family of numerous genera and species mainly confined to the Himalayas, but with a few straggling species in the Malay countries and the mountains of China; the Pteroptochidæ, large wren-like birds, consisting of eight genera and nineteen species, almost entirely confined to temperate South America and the Andes; and the birds-of-paradise, consisting of nineteen or twenty genera and about thirty-five species, almost all inhabitants of New Guinea and the immediately surrounding islands, while a few, doubtfully belonging to the family, extend to East Australia. Among reptiles the most striking case of restriction is that of the rough-tailed burrowing snakes (Uropeltidæ), the five genera and eighteen species being strictly confined to Ceylon and the southern parts of the Indian Peninsula.

The Distribution of Orders.—When we pass to the larger groups, termed orders, comprising several families, we find comparatively few cases of restriction and many of worldwide distribution; and the families of which they are composed are strictly comparable to the genera of which families are composed, inasmuch as they present examples of overlapping, or conterminous, or isolated areas, though the latter are comparatively rare. Among mammalia the Insectivora offer the best example of an order, several of whose families inhabit areas more or less isolated from the rest; while the Marsupialia have six families in Australia, and one, the opossums, far off in America.

Perhaps, more important is the limitation of some entire orders to certain well-defined portions of the globe. Thus the Proboscidea, comprising the single family and genus of the elephants, and the Hyracoidea, that of the Hyrax or Syrian coney, are confined to parts of Africa and Asia; the Marsupials to Australia and America; and the Monotremata, the lowest of all mammals—comprising the duck-billed Platypus and the spiny Echidna, to Australia and New Guinea. Among birds the Struthiones or ostrich tribe are almost confined to the three Southern continents, South America, Africa and Australia; and among Amphibia the tailed Batrachia—the newts and salamanders—are similarly restricted to the northern hemisphere.

These various facts will receive their explanation in a future chapter.

CHAPTER III

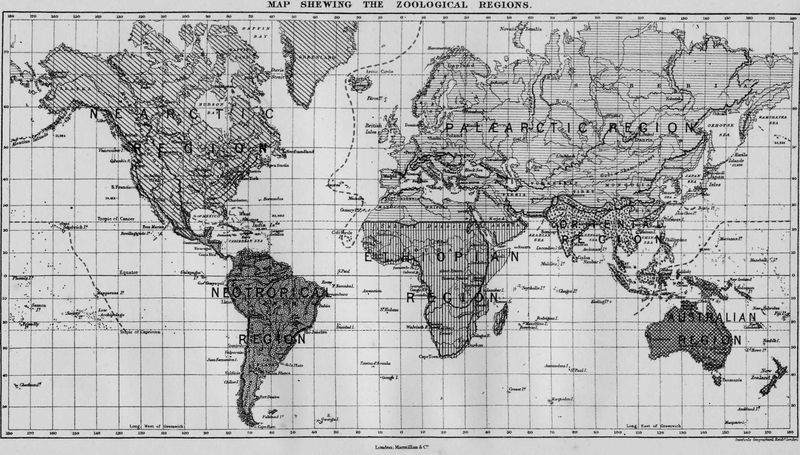

CLASSIFICATION OF THE FACTS OF DISTRIBUTION.—ZOOLOGICAL REGIONS

The Geographical Divisions of the Globe do not correspond to Zoological divisions—The range of British Mammals as indicating a Zoological Region—Range of East Asian and North African Mammals—The Range of British Birds—Range of East Asian Birds—The limits of the Palæarctic Region—Characteristic features of the Palæarctic Region—Definition and characteristic groups of the Ethiopian Region—Of the Oriental Region—Of the Australian Region—Of the Nearctic Region—Of the Neotropical Region—Comparison of Zoological Regions with the Geographical Divisions of the Globe.

Having now obtained some notion of how animals are dispersed over the earth's surface, whether as single species or as collected in those groups termed genera, families, and orders, it will be well, before proceeding further, to understand something of the classification of the facts we have been considering, and some of the simpler conclusions these facts lead to.

We have hitherto described the distribution of species and groups of animals by means of the great geographical divisions of the globe in common use; but it will have been observed that in hardly any case do these define the limits of anything beyond species, and very seldom, or perhaps never, even those accurately. Thus the term "Europe" will not give, with any approach to accuracy, the range of any one genus of mammals or birds, and perhaps not that of half-a-dozen species. Either they range into Siberia, or Asia Minor, or Palestine, or North Africa; and this seems to be always the case when their area of distribution occupies a large portion of Europe. There are, indeed, a few species limited to Central or Western or Southern Europe, and these are almost the only cases in which we can use the word for zoological purposes without having to add to it some portion of another continent. Still less useful is the term Asia for this purpose, since there is probably no single animal or group confined to Asia which is not also more or less nearly confined to the tropical or the temperate portion of it. The only exception is perhaps the tiger, which may really be called an Asiatic animal, as it occupies nearly two-thirds of the continent; but this is an unique example, while the cases in which Asiatic animals and groups are strictly limited to a portion of Asia, or extend also into Europe or into Africa or to the Malay Islands, are exceedingly numerous. So, in Africa, very few groups of animals range over the whole of it without going beyond either into Europe or Asia Minor or Arabia, while those which are purely African are generally confined to the portion south of the tropic of Cancer. Australia and America are terms which better serve the purpose of the zoologist. The former defines the limit of many important groups of animals; and the same may be said of the latter, but the division into North and South America introduces difficulties, for almost all the groups especially characteristic of South America are found also beyond the isthmus of Panama, in what is geographically part of the northern continent.

It being thus clear that the old and popular divisions of the globe are very inconvenient when used to describe the range of animals, we are naturally led to ask whether any other division can be made which will be more useful, and will serve to group together a considerable number of the facts we have to deal with. Such a division was made by Mr. P. L. Sclater more than twenty years ago, and it has, with some slight modifications, come into pretty general use in this country, and to some extent also abroad; we shall therefore proceed to explain its nature and the principles on which it is established, as it will have to be often referred to in future chapters of this work, and will take the place of the old geographical divisions whose inconvenience has already been pointed out. The primary zoological divisions of the globe are called "regions," and we will begin by ascertaining the limits of the region of which our own country forms a part.

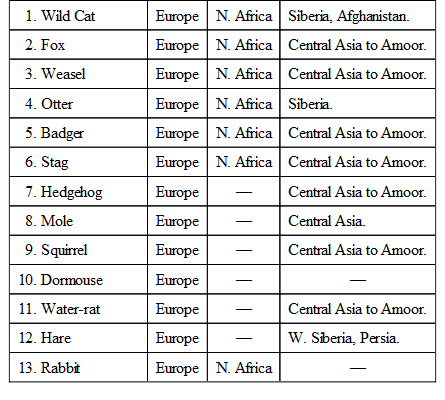

The Range of British Mammals as indicating a Zoological Region.—We will first take our commonest wild mammalia and see how far they extend, and especially whether they are confined to Europe or range over parts of other continents:

We thus see that out of thirteen of our commonest quadrupeds only one is confined to Europe, while seven are found also in Northern Africa, and eleven range into Siberia, most of them stretching quite across Asia to the valley of the Amoor on the extreme eastern side of that continent. Two of the above-named British species, the fox and weasel, are also inhabitants of the New World, being as common in the northern parts of North America as they are with us; but with these exceptions the entire range of our commoner species is given, and they clearly show that all Northern Asia and Northern Africa must be added to Europe in order to form the region which they collectively inhabit. If now we go into Central Europe and take, for example, the quadrupeds of Germany, we shall find that these too, although much more numerous, are confined to the same limits, except that some of the more arctic kinds, as already stated, extend into the colder regions of North America.

Range of East Asian and North African Mammals.—Let us now pass to the other side of the great northern continent, and examine the list of the quadrupeds of Amoorland, in the same latitude as Germany. We find that there are forty-four terrestrial species (omitting the bats, the seals, and other marine animals), and of these no less than twenty-six are identical with European species, and twelve or thirteen more are closely allied representatives, leaving only five or six which are peculiarly Asiatic. We can hardly have a more convincing proof of the essential oneness of the mammalia of Europe and Northern Asia.

In Northern Africa we do not find so many European species (though even here they are very numerous) because a considerable number of West Asiatic and desert forms occur. Having, however, shown that Europe and Western Asia have almost identical animals, we may treat all these as really European, and we shall then be able to compare the quadrupeds of North Africa with those of Europe and West Asia. Taking those of Algeria as the best known, we find that there are thirty-three species identical with those of Europe and West Asia, while twenty-four more, though distinct, are closely allied, belonging to the same genera; thus making a total of fifty-seven of European type. On the other hand, we have seven species which are either identical with species of tropical Africa or allied to them, and six more which are especially characteristic of the African and Asiatic deserts which form a kind of neutral zone between the temperate and tropical regions. If now we consider that Algeria and the adjacent countries bordering the Mediterranean form part of Africa, while they are separated from Europe by a wide sea and are only connected with Asia by a narrow isthmus, we cannot but feel surprised at the wonderful preponderance of the European and West Asiatic elements in the mammalia which inhabit the district.

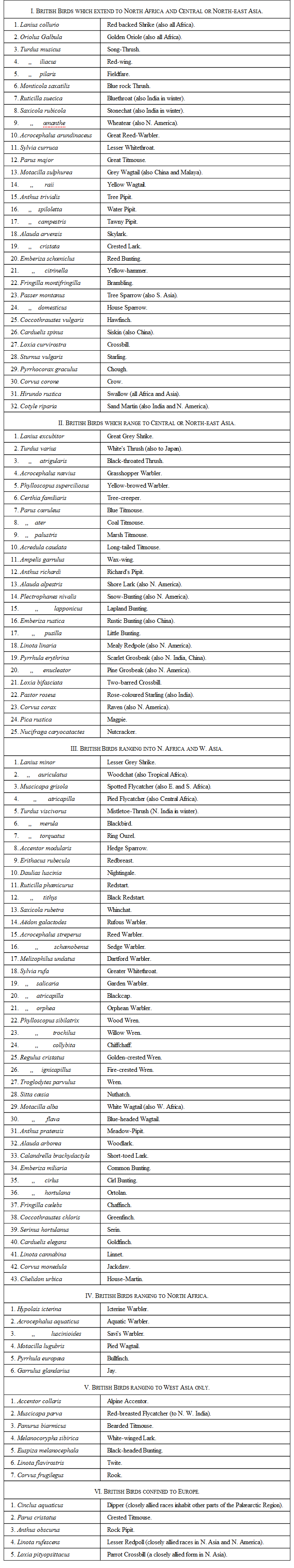

The Range of British Birds.—As it is very important that no doubt should exist as to the limits of the zoological region of which Europe forms a part, we will now examine the birds, in order to see how far they agree in their distribution with the mammalia. Of late years great attention has been paid to the distribution of European and Asiatic birds, many ornithologists having travelled in North Africa, in Palestine, in Asia Minor, in Persia, in Siberia, in Mongolia, and in China; so that we are now able to determine the exact ranges of many species in a manner that would have been impossible a few years ago. These ranges are given for all British species in the new edition of Yarrell's History of British Birds edited by Professor Newton, while those of all European birds are given in still more detail in Mr. Dresser's beautiful work on the birds of Europe. In order to confine our examination within reasonable limits, and at the same time give it the interest attaching to familiar objects, we will take the whole series of British Passeres or perching birds given in Professor Newton's work (118 in number) and arrange them in series according to the extent of their range. These include not only the permanent residents and regular migrants to our country, but also those which occasionally straggle here, so that it really comprises a large proportion of all European birds.

We find, that out of a total of 118 British Passeres there are:

32 species which range to North Africa and Central or East Asia.

25 species which range to Central or East Asia, but not to North Africa.

43 species which range to North Africa and Western Asia.

6 species which range to North Africa, but not at all into Asia.

7 species which range to West Asia, but not to North Africa.

5 species which do not range out of Europe.

These figures agree essentially with those furnished by the mammalia, and complete the demonstration that all the temperate portions of Asia and North Africa must be added to Europe to form a natural zoological division of the earth. We must also note how comparatively few of these overpass the limits thus indicated; only seven species extending their range occasionally into tropical or South Africa, eight into some parts of tropical Asia, and six into arctic or temperate North America.

Range of East Asian Birds.—To complete the evidence we only require to know that the East Asiatic birds are as much like those of Europe, as we have already shown to be the case when we take the point of departure from our end of the continent. This does not follow necessarily, because it is possible that a totally distinct North Asiatic fauna might there prevail; and, although our birds go eastward to the remotest parts of Asia, their birds might not come westward to Europe. The birds of Eastern Siberia have been carefully studied by Russian naturalists and afford us the means of making the required comparison. There are 151 species belonging to the orders Passeres and Picariæ (the perching and climbing birds), and of these no less than 77, or more than half, are absolutely identical with European species; 63 are peculiar to North Asia, but all except five or six of these are allied to European forms; the remaining 11 species are migrants from South-eastern Asia. The resemblance is therefore equally close whichever extremity of the Euro-Asiatic continent we take as our starting point, and is equally remarkable in birds as in mammalia. We have now only to determine the limits of this, our first zoological region, which has been termed the "Palæarctic" by Mr. Sclater, meaning the "northern old-world" region—a name now well known to naturalists.

The Limits of the Palæarctic Region.—The boundaries of this region, as nearly as they can be ascertained, are shown on our general map at the beginning of this chapter, but it will be evident on consideration, that, except in a few places, its limits can only be approximately defined. On the north, east, and west it extends to the ocean, and includes a number of islands whose peculiarities will be pointed out in a subsequent chapter; so that the southern boundary alone remains, but as this runs across the entire continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific ocean, often traversing little-known regions, we may perhaps never be able to determine it accurately, even if it admits of such determination. In drawing the boundary line across Africa we meet with our first difficulty. The Euro-Asiatic animals undoubtedly extend to the northern borders of the Sahara, while those of tropical Africa come up to its southern margin, the desert itself forming a kind of sandy ocean between them. Some of the species on either side penetrate and even cross the desert, but it is impossible to balance these with any accuracy, and it has therefore been thought best, as a mere matter of convenience, to consider the geographical line of the tropic of Cancer to form the boundary. We are thus enabled to define the Palæarctic region as including all north temperate Africa; and, a similar intermingling of animal types occurring in Arabia, the same boundary line is continued to the southern shore of the Persian Gulf. Persia and Afghanistan undoubtedly belong to the Palæarctic region, and Baluchistan should probably go with these. The boundary in the north-western part of India is again difficult to determine, but it cannot be far one way or the other from the river Indus as far up as Attock, opposite the mouth of the Cabool river. Here it will bend to the south-east, passing a little south of Cashmeer, and along the southern slopes of the Himalayas into East Thibet and China, at heights varying from 9,000 to 11,000 feet according to soil, aspect, and shelter. It may, perhaps, be defined as extending to the upper belt of forests as far as coniferous trees prevail; but the temperate and tropical faunas are here so intermingled that to draw any exact parting line is impossible. The two faunas are, however, very distinct. In and above the pine woods there are abundance of warblers of northern genera, with wrens, numerous titmice, and a great variety of buntings, grosbeaks, bullfinches and rosefinches, all more or less nearly allied to the birds of Europe and Northern Asia; while a little lower down we meet with a host of peculiar birds allied to those of tropical Asia and the Malay Islands, but often of distinct genera. There can be no doubt, therefore, of the existence here of a pretty sharp line of demarkation between the temperate and tropical faunas, though this line will be so irregular, owing to the complex system of valleys and ridges, that in our present ignorance of much of the country it cannot be marked in detail on any map.