полная версия

полная версияThe Violoncello and Its History

Another Italian cellist of that time was Domenico della Bella, of whom nothing further is known than that, in 1704, he published, in Venice, Twelve Sonatas “a due violini e violoncello.”

The information is equally meagre regarding the cellist Parasisi, of whom Gerber says he was an extraordinary artist on his instrument and was with the Italian Opera orchestra at Breslau in 1727.

Concerning the Italian violoncellists Jacchini, Amadio, Vandini, Abaco, dall’Oglio, and Lanzetti, born in the second half of the seventeenth and the beginning of the eighteenth century, we know very little.

Jacchini, whose Christian name was Giuseppe, noted by Gerber as one of the first cellists of his time, was appointed to the church of S. Petronio in Bologna at the beginning of the eighteenth century. That he had distinguished himself as an artist is proved by his nomination as a member of the Bologna Philharmonic Society, a distinction which is only conferred on men of great musical reputation. Of his compositions there is a work entitled “Concerti per Camera a 3 e 4 stromenti, con violoncello obligato (Op. 4). Bologna, 1701,” to be mentioned.

Pippo Amadio, who flourished about the year 1720, was, according to Gerber’s account, a violoncellist, “whose art surpassed all, that up to his time had been produced on his instrument.”

Antonio Vandini, first violoncellist at the church of S. Antonio, Padua, seems to have been no less remarkable. The Italians called his manner of playing and his expression “parlare”—he understood how to make his instrument speak. He was on terms of such close friendship with Tartini, who as is known was engaged at the same church at Padua as solo violinist, that he accompanied him in 1723 to Prague, and remained with him for three years in the service of Count Kinski. Vandini was still living in Padua in 1770. The year of his death is unknown.

Abaco, born at Verona, according to information contained in the second year of the “Leipsic Musical Paper” (p. 345), was a prominent violoncellist, who lived in the first half of the eighteenth century. Gerber possessed a cello solo of his composition, of which he says that it appeared to have been written in the year 1748.

Giuseppe dall’Oglio, the younger brother of the famous violin player, Domenico dall’Oglio, was born about 1700 at Padua,63 and went to St. Petersburg in 1735. There he remained in the Russian imperial service twenty-nine years, after which he returned to his native land. On his journey thither he stopped at Warsaw, on which occasion King August of Poland nominated him his agent for the Venetian Republic.

Salvatore Lanzetti, born at the beginning of the eighteenth century in Naples, was pupil of the Conservatorio there, Santa Maria di Loreto, and was during the greater part of his life in the service of the King of Sardinia. He died in Turin in 1780. In the year 1736 two volumes of violoncello sonatas appeared by him, and later also a book of instruction, the title of which Fétis gives as: “Principes du doigter pour le Violoncelle dans tous les tons.” It is somewhat differently named by Gerber: “Principes ou l’applicatur de Violoncel par tous les tons.” Lanzetti must have carried out with great skill the staccato touch both up and down the instrument.

We are somewhat better informed regarding the violoncellist Caporale. Neither the place of his home nor the year of his birth nor that of his death are, indeed, known to us, but of his life and work in England we possess some information. In 1735 he came to London and worked under Handel, who wrote for him a cello solo in the third act of his opera “Deidamia” composed in 1739.

His musical education could not have been very thorough, but he must have had certain qualifications which induced Handel to connect himself with him. Simpson’s Collection (see p. 49), published in London, contains a Cello Sonata by Caporale, which does not speak much for his talent in composition. It consists of Adagio, Allegro, and a Theme with three variations after the manner of studies. As a player Caporale was remarkable for his tone, but as regards finish he could not rival either the elder Cervetto or Pasqualini.

This last-named artist, by whom a sonata, scarcely rising above the level of Caporale, was contained in the volume already mentioned as appearing at Simpson’s, was performing in London, in 1745, as a concertist of great repute. Further information regarding him does not exist.

Greater consideration must be yielded to Carlo Ferrari, brother of the violinist Domenico Ferrari, so often referred to in the previous century. On account of an injured foot he was called “the lame.” Born at Piacenza about 1730 he betook himself to Paris in 1758 and appeared with great success in the “Concert Spirituel.” In 1765 he accepted an engagement offered to him by the Count of Parma.64 He remained in this position until his death, which took place in 1789. It is reported of Ferrari that he was the first Italian cellist who made use of the thumb position. If this be true, France must have been beforehand in the difficult matter of the art of fingering; for the thumb position was already known in Paris, as we have seen, before 1740, consequently at a time when Ferrari was only ten or twelve years old. But if it be acknowledged that violoncello playing was cultivated much earlier in Italy than in France, and had already advanced beyond the elemental stage before it had found representatives among the French, we must be inclined to concede to the Italians the discovery of the thumb position, and indeed to the predecessors of Ferrari. It is highly probable that Franciscello and Batistin already availed themselves of its assistance for the use of the upper parts of the fingerboard. The trick must have been brought into France by the last-named artist who, as we know, settled in Paris at the beginning of the eighteenth century.

The proof that the thumb position was known in Paris before 1740 is established by the violoncello method of Michel Corrette in the year 1741, and which, as far as one can see, was the first work of instruction for the instrument in question. Considering the scarcity at that time of cello compositions this instruction book is the more important, as from it is to be determined with certainty the average standard to which violoncello playing had attained towards the middle of the previous century. This circumstance seems to justify our entering somewhat more fully into Corrette’s school.

The title is: “Méthode, théoretique et pratique, pour apprendre en peu de temps, le violoncelle … dans sa perfection composée par Michel Corette. XXIVe Ouvrage à Paris, chez l’auteur, Me Boivin et le Sr le Clerc; à Lyon chez M. de Bretonne. Avec Privilège du Roy. MDCCXL1.”65

After some introductory paragraphs regarding the use of the F and C clef, in notation for violoncello music, concerning the value of notes and pauses, the formation of sharps, flats, and naturals, as well as regarding the usual marks, the various measures and syncopes, Corrette treats:

1. Of the manner of holding the violoncello; 2. Of the holding and action of the bow; 3. Of its use in the up and down strokes; 4. Of the tuning of the violoncello; 5. Of the division of the fingerboard into diatonic as well as chromatic tones; 6. Of the fingering in the lower (first) and following positions; 7. Of the way and manner of returning from the higher positions to the first; 8. Of trills and appogiaturas; 9. Of the various kinds of bow action; 10. Of double-stops and arpeggios; 11. And also of the thumb position. He also gives instruction for those who wish to go from the gamba to the violoncello, and then in conclusion gives hints for the accompaniment of singing and for instrumental solos.

It is evident that the directions of Corrette have chiefly a mere historical importance, as the technique of the violoncello, after the appearance of his method, underwent substantial changes. His explanation concerning the finger positions of that period and the thumb position which in the higher parts of the fingerboard takes the place of a moveable nut, concerning the manipulation of the bow, and the considerations to be observed in exchanging the gamba for the violoncello have a special interest for us.

With regard to the first of these four points, we remark that the finger position adopted by Corrette for the diatonic scale on all the strings was, in the first two positions, 1, 2, and 4; in the “third position,” 1, 2, 3, 4; and in the “fourth,” 1, 2, and 3; after the latter position the fourth finger was as a rule no longer needed, for which Corrette adduces as a reason that it is too short to be made use of in the higher positions of the fingerboard; in case however it should be necessary to use it, the use of the left arm would be impeded. In exceptional cases, says Corrette in another part of his school, the fourth finger could be used in the “fourth position,” without altering the thumb position, for the B flat and B on the A string, for the E flat on the D string, for the A flat on the G string, and for the D flat on the C string. The finger positions were then, in the first half and about the middle of the last century, somewhat different in the diatonic scale of the violoncello than they were later on. It is especially to be remarked that the E and the B were touched with the second finger upon the two lower strings, though the notes marked were far more convenient for the third finger, which very shortly took the place of the second.

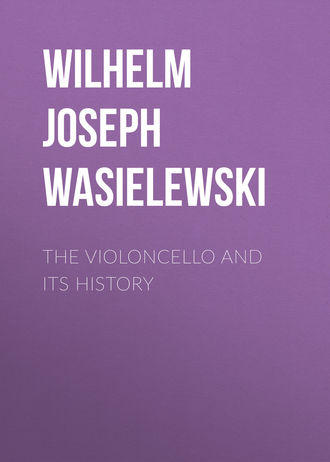

As to the exclusion of the fourth finger, when playing with the thumb position, no proof is needed to show the reason was that it gave an awkward manner of holding the left hand. The finger positions for the chromatic scale still more widely differed from the fingering employed later, as the following scale shows—

It very nearly happened, that as early as the seventeenth century when a stringed instrument was so much desired as a standard one for the violoncello, that the violin mode of fingering was adopted for the former, which according to the foregoing remarks really was the case, with the exception of the use of the third finger. It had however been overlooked that the cello, on account of its much larger dimensions, demanded an entirely different method of fingering. The regulation of this important point, which offered peculiar difficulties, occupied cellists up to the beginning of our century. In some measure the fingering which Corrette teaches for descending intervals of a second from the higher to the lower tones is unavoidable. He gives the two following examples—

He gave the preference to the second example.

The almost total exclusion of the fourth finger caused a very great restriction in playing with the thumb position. But when Corrette wrote his work this limitation would hardly have been felt, as the higher parts of the fingerboard were little, and, only in exceptional cases, used by cello players and composers. Corrette mentions, as the highest tone, the one-lined B. Caporale and Pasqualini do not go beyond this note in their sonatas, already mentioned, excepting in one instance, when Caporale casually uses the two-lined C. It appears that, with many cellists, in place of the thumb the first finger was made use of in the higher positions as a support, for Corrette remarks concerning his method: “If the first finger is used instead of the thumb the fourth finger must necessarily be made use of; it is, however, on account of its shortness, really useless in the upper ‘positions.’” To beginners Corrette recommended the attempt then in vogue—but a little later combated by Leopold Mozart in his violin school66—to introduce marks on the fingerboard indicating the intervals in order to learn to play clearly in tune. For gamba players who, following the spirit of the time, gave up their instrument and turned to the violoncello, which was rapidly coming into use, this means of assistance had a certain value, accustomed as they were to the frets of the gamba fingerboard, for the finger positions of both instruments differ considerably from one another, as appears from the comparison given below by Corrette.

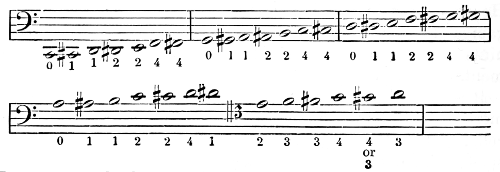

Scale on the gamba.

7. String. 6. String. 5. String. 4. String. 3. String. 2. String. 1. String.

Scale on the Cello.

C String. G String. D String. A String. Thumb-position.

The figures placed under the gamba scale relate to the frets which are to be attended to by the player, while those of the cello scale are the finger positions to be used.

The lower C, which the string itself forms on the cello, had on the gamba to be touched at the third fret; the succeeding D on the gamba was the open string, while on the cello it was to be touched with the first finger, and so on.

The four highest tones, e, f, g, a, fell in the gamba on the 2nd, 3rd, 5th, and 7th frets, whereas, according to Corrette’s account, those in the cello required the use of the thumb position. It is plain that the gamba players who took up the violoncello had to adopt an entirely different system of fingering.

To a certain extent the handling of the bow presented difficulties to those who exchanged the gamba for the violoncello. The former instrument, on account of the flatness of the bridge, did not allow of an energetic use of the bow. From the violoncello, on the contrary, a powerful tone must be brought out, which had to be learnt by gamba players. Besides, they had also to accustom themselves to other strokes of the bow for the cello. What was played by the latter instrument with a down stroke, was played by an upward one on the gamba, and the reverse.

The holding of the bow was again rather different from the present manner. Corrette gives three ways for this. According to Corrette’s testimony, the most usual way in Italy consisted in placing the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th fingers upon the rod and the thumb beneath it, so that the bow was held not exactly at the nut, but about a hand’s breadth from it, as formerly and even at the beginning of our century was done by many players. The second way of holding the bow was, the other four fingers being placed as above, to lay the thumb upon the hair. Finally, the bow was also held, so that the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th fingers were laid upon that part of the rod to which the nut is attached, while the thumb had its place beneath the nut.

Corrette does not give the preference to either of these ways of holding the bow, which in the course of the second half of the last century became more and more obsolete. He was of opinion that they were all good, but left it to each one to choose the manner in which the most power could be attained. It seems, however, noteworthy that Corrette laid it down as a rule that the middle of the bow should be used in playing, whereby its use was limited to a third of its length.

In the preface to his method Corrette speaks of several systems amongst violoncellists, but adds, the best and most generally followed was that of Bononcini, of which also the most skilful masters in Europe made use. From this remark it follows, that in the composition of his school, he took Bononcini’s manner of playing, which he was able to study, soon after the latter’s arrival in Paris, as his guide. In surveying the above principles, detailed by Corrette, regarding the technique of violoncello playing, it must be admitted that, needing improvement in almost every respect about the middle of the last century, it had not progressed, with few exceptions, beyond the elementary stages. The chamber sonatas and suites of Joh. Seb. Bach for violoncello solo, the last of which were originally composed for the Viola pomposa, cannot be cited as proofs to the contrary. In them Bach forestalled the technical capacity of his time by a decade. Although they are composed for that part of the fingerboard on which there is no question of the thumb position, yet they contain difficulties of an extraordinary kind which Bach’s contemporaries had not been able to master.67 And even in the second half of the last century there could have been no cellist who would have been fully capable of playing them. Therefore it must be considered either, that these compositions, so remarkable of their kind, were not absolutely composed for the cello; or that the violoncello technique took another direction, which was called out by these suites of Bach.

The violoncello, like the violin, is primarily an instrument for the voice. As such it was chiefly used by the Italians, who, up to the second half of the last century, gave the impulse to stringed instrument playing. This is to be gathered from the cello pieces by Italian composers belonging to this period. As instances, next to the sonatas already mentioned, two musical pieces of the same kind may be cited, by San Martini (Giov. Battista Sammartini)68 and Bernardo Porta.69 Neither of these composers were violoncellists. Their sonatas are, however, adapted to the nature of the instrument for which they were composed. As compositions they are indeed of little importance, and as regards the technique, they do not rise above the measure of the modest demands which were then required.

With regard to cello technique the younger Cervetto, whose compositions have already been mentioned, p. 52, goes really farther. In them there is a greater variety in the manner of playing, in the use of double-stops and different passages derived from the scale and the chord. Such ways of playing could naturally only at first be found out and perfected in a proper manner by those who were already experienced practised players on an instrument of extreme difficulty on account of its extensions.

The cello pieces of Cervetto formed after the manner of Tartini’s violin sonatas are, as to their contents, quite antiquated, and are only interesting in a purely technical point of view. Like the compositions already considered, they occupy mostly the parts of tenor and bass. Only twice in the first Allegro of the tenth Sonata of his Op. 4 does Cervetto venture to the twice-lined E, and at the conclusion of the same piece to the twice-lined A. In both cases he has to use the treble clef, which does not appear elsewhere.

Besides Cervetto the younger, amongst Italians who cultivated cello playing must be mentioned Gasparini, Moria, Joannini di Violoncello, Zappa, Cirri, Aliprandi, Graziani, Piarelli, Spotorni I. and II., Barni, Bertoja I. and II., Lolli, Sandonati, and Shevioni. We give below the meagre information which exists regarding them.

Quirino Gasparini, a distinguished cellist, was in 1749 Kapellmeister at the Court of Turin. He remained there until 1770. As a composer, he was chiefly occupied with church music, no cello pieces are known by him.

Of Moria, the fact only is known that, in 1755, he was heard at the “Concert Spirtuel” in Paris.

Joannini di Violoncello, from the year 1759 Kapellmeister at St. Petersburg, had a great reputation in his own country as a player.

Zappa, called Francesco, according to Gerber was making a concert tour in 1781, and “enchanted his hearers in Dantsic by his soft and delightful execution.”

Giambattista Cirri, born in the first half of the eighteenth century, at Forli, lived and worked for a long time in England. On the title page of his first work, published at Verona in 1763, he called himself a “Professore di Violoncello.” Of his compositions there appeared in print seventeen different works in London, Paris, and Florence.

As a clever violoncellist, Bernardo Aliprandi, son of the opera composer, Aliprandi, born in Tuscany, was distinguished. His father was composer and Court band-conductor in Munich during the first half of the previous century; but he himself became a member of the orchestra there, where he still was in 1786. His cello pieces, of which several were published, are as obsolete as those of Cirri.

Gerber, in his dictionary, says of Graziani, that after the death of the gamba player, Louis Christian Hesse,70 he was summoned to Potsdam to take his place as tutor to the Crown Prince of Prussia. When the French violoncellist, Duport (the elder), came to Berlin, in 1773, Graziani lost his post at Court. He died at Potsdam in 1787. The six violoncello solos, Op. 1 (printed in Berlin about the year 1780), as well as the six cello pieces brought out in Paris (Op. 2), mentioned by Gerber in his old Musical Dictionary under the name of Graziani, must have appeared in the latter years of the author’s life.

In the second half of the last century there was a violoncello virtuoso, by name Piarelli, who, about 1784, had printed in Paris six violoncello solos. This is all that is known about him.

Of the brothers Spotorni, Gerber only says that, in 1770, in Italy, “their native land, they were esteemed as violoncellists.”

A very skilful player was Camillo Barni, born on January 18, 1762, at Como. He received his first instructions in cello playing at the age of fourteen years from his grandfather, David Ronchetti. Later on, Giuseppe Gadgi, Canon of the Cathedral at Como, taught him for a few months. At the age of twenty Barni joined the opera orchestra of Milan, of which he became first violoncellist in 1791. In the year 1802 he went to reside permanently in Paris, where he appeared as solo player, and then, for several years, was an active member in the orchestra of the Italian Opera. Between 1804 and 1809 he published several duets for his own instrument and the violin. He also wrote a cello concerto.

Concerning the brothers Bertoja, Gerber only says that both were employed in Venice about 1800, as virtuosi on the violoncello, and were reputed in Italy the first masters of their instrument.

Filippo Lolli, son of the violin virtuoso, Antonio Lolli, was born at Stuttgard, in 1773; practised the cello from early youth, and at eighteen years of age made a concert tour, which led him to Berlin. Here he was heard by the King, who was so pleased with his performance that he recognised it by an honorarium of 100 louis d’or. Lolli then went to Copenhagen, and in the year 1804 played at concerts in Vienna. There is no more information about him extant.

Of Sandonati, Gerber says that he lived in Verona in 1800, and was one of the most renowned violoncellists of those times. Gerber announces the same of the Mantuan, Shevioni, who worked about the same time apparently in Verona.

While all these men were endeavouring to make an advance in violoncello playing, and especially in violoncello compositions, the Italian nation possessed in Boccherini an artist who surpassed in every direction his countrymen.

Luigi Boccherini, the son of a contra-basso player, was born on February 19, 1743, at Lucca. He there received his first musical instruction from the archbishop’s choirmaster, Vanucci. Besides the cultivation of theory, he devoted himself with peculiar zeal to cello playing, of which he was to prove a master. The very promising progress which he made decided his father to send him to Rome for the further prosecution of his studies, and where his talents attained their full development.

When Boccherini, after the course of a few years, returned to his native town, he found there Tartini’s pupil, Filippo Manfredini, his countryman, who was an excellent violinist. He soon formed an intimate friendship with him, which led to an arrangement for making a concert tour. The two artists went to Spain, afterwards to Piedmont, to Lombardy, and the South of France. The favourable reception which the friends experienced encouraged them about 1768 to proceed to Paris. In the French capital they had a splendid success. The compositions of Boccherini gained such great applause that the Parisian music publishers, La Chevardière and Venier, declared themselves ready to undertake the expense of printing all the works already heard. Notwithstanding, he received very little for his compositions, and later on he was not more fortunate.

At the persuasion of the Spanish ambassador in Paris the artists proceeded, at the end of 1768, or the beginning of the next year, to Madrid. Here Boccherini roused the special interest of the Infanta Don Luis, who named him his “Compositore e virtuoso di camera.” When this prince died, on August 7, 1785, Boccherini became Court Kapellmeister of King Charles III. of Spain, a post which he also filled under the succeeding king, Charles IV. He received a still further recognition from the King Frederick William II. of Prussia, who designated him his chamber-composer, when he, in the year 1787, dedicated a work to this art-loving monarch, who conferred on him a considerable honorarium. From that time Boccherini dedicated to him everything that he composed. We may conclude that he was adequately remunerated, for when the king died in November, 1797, and the allowance ceased, Boccherini fell into difficulties, his compositions being badly paid by the publishers. At the same time he seems to have lost his place as Kapellmeister to the King of Spain. However it was, he spent the last years of his life with his family in great need, from which death only released him on May 28, 1805.