полная версия

полная версияOur Cats and All About Them

Studying closely the habits of the cat for years, as I have, I believe there is a natural sullen antipathy to being taught or restrained, or made to do anything to which its nature or feelings are averse; and this arises from long-continued persecution and no training. Try, for instance, to make a cat lie still if it wants to go out. You may hold it at first, then gently relinquish your grasp, stroke it, talk to it, fondle it, until it purrs, and purrs with seeming pleasure, but it never once forgets it is restrained, and the first opportunity it will make a sudden dash, and is—gone.

However, all animals, more or less, may be trained, and the cat, of course, is among them, and a notable one. By bringing them up among birds, such as canaries, pigeons, chickens, and ducklings, it will respect and not touch them, while those wild will be immediately sacrificed.

One of the best instances of this was a small collection of animals and birds in a large cage that used to be shown by a man by the name of Austin, and to which I have already referred. This man was a lover and trainer of animal life, and an adept. His "Happy Family" generally consisted of a cat or two, some kittens, rats, mice, rabbits, guinea pigs, an owl, a kestrel falcon, starlings, goldfinches, canaries, etc.—a most incongruous assembly. Yet among them all there was a freedom of action, a self-reliance, and an air of happiness that I have never seen in "performing cats." Mr. Austin informed me that he had been a number of years studying their different natures, but that he found the cats the most difficult to deal with, only the most gentle treatment accomplishing the object he had in view. Any fresh introduction had to be done by degrees, and shown outside first for some time. It was quite apparent, however, that the cats were quite at their ease, and I have seen a canary sitting on the head of the cat, while a starling was resting on the back. But all are gone—Austin and his pets—and no other reigns in his stead.

Occasionally one sees, at the corners of some of the London streets, a man who professes to have trained cats and birds; the latter, certainly, are clever, but the former have a frightened, scared look, and seem by no means comfortable. I should say the tuition was on different lines to that of Austin. The man takes a canary, opens a cat's mouth, puts it in, takes it out, makes the cat, or cats, go up a short ladder and down another; then they are told to fight, and placed in front of each other; but fight they will not with their fore-paws, so the master moves their paws for them, each looking away from the other. There is no training in this but fear. There is an innate timidity, the offspring of long persecution, in the cat that prevents, as a rule, its performing in public. Not so the dog; time and place matter not to him; from generation to generation he has been used to it.

In "Cats Past and Present," by Champfleury, there are descriptions of performing cats, and one Valmont de Bomare mentions that in a booth at the fair of St. Germain's, during the eighteenth century, there was a cat concert, the word "Miaulique," in huge letters, being on the outside. In 1789 there is an account of a Venetian giving cat concerts, and the facsimile of a print of the seventeenth century picturing a cat showman.

"In 1758, or the following year, Bisset, the famous animal trainer, hired a room near the Haymarket, at which he announced a public performance of a 'Cats' Opera,' supplemented by tricks of a horse, a dog, and some monkeys, etc. The 'Cats' Opera' was attended by crowded houses, and Bisset cleared a thousand pounds in a few days. After a successful season in London, he sold some of the animals, and made a provincial tour with the rest, rapidly accumulating a considerable fortune."—Mr. Frost's Old Showman.

"Many years ago a concert was given at Paris, wherein cats were the performers. They were placed in rows, and a monkey beat time to them. According as he beat the time so the cats mewed; and the historian of the fact relates that the diversity of the tones which they emitted produced a very ludicrous effect. This exhibition was announced to the Parisian public by the title of Concert Miaulant."—Zoological Anecdotes.

Another specimen of discipline is to be found in "Menageries." The writer says: "Cats may be taught to perform tricks, such as leaping over a stick, but they always do such feats unwillingly. There is at present an exhibition of cats in Regent Street, who, at the bidding of their master, an Italian, turn a wheel and draw up water in a bucket, ring a bell; and in doing these things begin, continue, and stop as they are commanded. But the commencez, continuez, arrêtez of their keeper is always enforced with a threatening eye, and often with a severe blow; and the poor creatures exhibit the greatest reluctance to proceed with their unnatural employments. They have a subdued and piteous look; but the scratches upon their master's arms show that his task is not always an easy one."

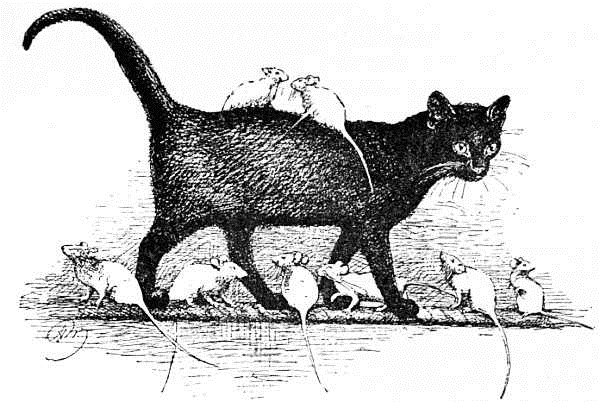

Of performing cats on the stage, there have been several "companies" of late in London, one of which I went to see at the royal Aquarium, Westminster; and I am bound to say that the relations between master and cats were on a better footing than any that have hitherto come under my notice. On each side of the stage there were cat kennels, from which the cats made their appearance on a given signal, ran across, on or over whatever was placed between, and disappeared quickly into the opposite kennels. But about it all there was a decided air of timidity, and an eagerness to get the performance over, and done with it. When the cats came out they were caressed and encouraged, which seemed to have a soothing effect, and I have a strong apprehension that they received some dainty morsel when they reached their destination. One ran up a pole at command, over which there was a cap at the top, into which it disappeared for a few seconds, evidently for some reason, food perhaps. It then descended. But before this supreme act several cats had crossed a bridge of chairs, stepping only on the backs, until they reached the opposite house or box into which to retire. The process was repeated, and the performance varied by two cats crossing the bridge together, one passing over and the other under the horizontal rung between the seat and the top of the chair. A long plank was next produced, upon which was placed a row of wine-bottles at intervals; and the cats ran along the plank, winding in and out between the bottles, first to the right, then to the left, without making a mistake. This part of the performance was varied by placing on the top of each bottle a flat disc of thick wood; one of the cats strode then from disc to disc, without displacing or upsetting a bottle, while the other animal repeated its serpentine walk on the plank below. The plank being removed, a number of trestles were brought in, and placed at intervals in a row between the two sets of houses, when the cats, on being called, jumped from trestle to trestle, varying the feat by leaping through a hoop, which was held up by the trainer between the trestles. To this succeeded a performance on the tight rope, which was not the least curious part of the exhibition. A rope being stretched across the arena from house to house, the cats walked across in turn, without making a mistake. Some white rats were then brought and placed at intervals along the rope, when the cats, re-crossing from one end to the other, strode over the rats without injuring them. A repetition of this feat was rendered a little more difficult by substituting for rats, which sat pretty quietly in one place, several white mice and small birds, which were more restless, and kept changing their positions. The cats re-crossed the rope, and passed over all these obstacles without even noticing the impediments placed in their way, with one or two exceptions, when they stopped, and cosseted one or more of the white rats, two of which rode triumphantly on the back of a large black cat.

Perhaps the most odd performance was that of "Cat Harris," an imitator of the voice of cats in 1747.

"When Foote first opened the Haymarket Theatre, amongst other projects he proposed to entertain the public with imitation of cat-music. For this purpose he engaged a man famous for his skill in mimicking the mewing of the cat. This person was called 'Cat Harris.' As he did not attend the rehearsal of this odd concert, Foote desired Shuter would endeavour to find him out and bring him with him. Shuter was directed to some court in the Minories, where this extraordinary musician lived; but, not being able to find the house, Shuter began a cat solo; upon this the other looked out of the window, and answered him with a cantata of the same sort. 'Come along,' said Shuter; 'I want no better information that you are the man. Foote stays for us; we cannot begin the cat-opera without you.'"—Cassell's Old and New London, vol. iv.

CAT-RACING IN BELGIUM

"On festival days, parties of young men assemble in various places to shoot with cross-bows and muskets, and prizes of considerable value are often distributed to the winners. Then there are pigeon-clubs and canary-clubs, for granting rewards to the trainers of the fleetest carrier-pigeons and best warbling canaries. Of these clubs many individuals of high rank are the honorary presidents, and even royal princes deign to present them banners, without which no Belgian club can lay claim to any degree of importance." But the most curious thing is cat-racing, which takes place, according to an engraving, in the public thoroughfare, the cats being turned loose at a given time. It is thus described: "Cat-racing is a sport which stands high in popular favour. In one of the suburbs of Liège it is an affair of annual observance during carnival time. Numerous individuals of the feline tribe are collected, each having round his neck a collar with a seal attached to it, precisely like those of the carrier-pigeons. The cats are tied up in sacks, and as soon as the clock strikes the solemn hour of midnight the sacks are unfastened, the cats let loose, and the race begins. The winner is the cat which first reaches home, and the prize awarded to its owner is sometimes a ham, sometimes a silver spoon. On the occasion of the last competition the prize was won by a blind cat."—Pictorial Times, June 16th, 1860.

CAT IMAGES

Those with long memories will not have forgotten the Italian with a board on his head, on which were tied a number of plaster casts, and possibly still seem to hear, in the far away time, the unforgotten cry of "Yah im-a-gees." Notably, among these works of art, were models of cats—such cats, such expressive faces; and what forms! How droll, too, were those with a moving head, wagging and nodding, as it were, with a grave and thoughtful, semi-reproachful, vacant gaze! "Yah im-a-gees" has passed on, and the country pedlar, with his "crockery" cats, mostly red and white. "Sure such cats alive were never seen?" but in burnt clay they existed, and often adorned the mantel-shelves of the poor. What must the live cat sitting before the fire have thought—if cats think—when it looked up at the stolid, staring, stiff and stark new-comer? One never sees these things now; nor the cats made of paste-board covered with black velvet, and two large brass spangles for eyes. These were put into dark corners with an idea of deception, with the imbecile hope that visitors would take them to be real flesh and bone everyday black cats. But was any one ever taken in but—the maker? Then there were cats, and cats and kittens, made of silk, for selling at fancy fairs, not much like cats, but for the purposes good. Cats sitting on pen-wipers; clay cats of burnt brick-earth. These were generally something to remember rather than possess. Wax cats also, with a cotton wick coming out at the top of the head. It was a saddening sight to see these beauties burning slowly away. Was this a "remnant" of the burning of the live cats in the "good old times?" And cats made of rabbits' skins were not uncommon, and far better to give children to play with than the tiny, lovable, patient, live kitten, which, if it submit to be tortured, it is well, but if it resent pain and suffering, then it is beaten. There is more ill done "from want of thought than want of heart."

But kittens have fallen upon evil times, ay, even in these days of education and enlightenment. As long as the world lasts probably there will be the foolish, the gay, unthinking, and, in tastes, the ridiculous. But then there are, and there ever will be, those that are always craving, thirsting, longing, shall I say mad?—for something new. Light-headed, with softened intellects who must—they say they must—have some excitement or some novelty, no matter what, to talk of or possess, though all this is ephemeral, and the silliness only lasts a few hours. Long or short, they are never conscious of these absurdities, and look forward with all the eagerness of doll-pleased infancy for another—craze. The world is being denuded of some of its brightest ornaments and its heaven-taught music, in the slaughter of birds, to gratify for scarcely a few hours the insane vanity, that is now rife in the ball-room—fashion.

What has all this to do with cats? Why, this class of people are not content, they never are so; but are adding to the evil by piling up a fresh one. It is the kitten now, the small, about two or three weeks old kitten that is the "fashion." Not long ago they were killed and stuffed for children to play with—better so than alive, perhaps; but now they are to please children of a larger growth, their tightly filled skins, adorned with glass eyes, being put in sportive attitudes about portrait frames, and such like uses. It is comical, and were it not for the stupid bad taste and absurdity of the thing, one would feel inclined to laugh at clambering kitten skins about, and supposed to be peeping into the face of a languor-struck "beauty." Who buys such? Does any one? If so, where do they go? Over thirty kittens in one shop window. What next, and—next? Truly frivolity is not dead!

From these, and such as these, turn to the models fair and proper; the china, the porcelain, the terra cotta, the bronze, and the silver, both English, French, German, and Japanese; some exquisite, with all the character, elegance, and grace of the living animals. In these there has been a great advance of late years, Miss A. Chaplin taking the lead. Then in bold point tracery on pottery Miss Barlow tells of the animal's flowing lines and non-angular posing. Art—true art—all of it; and art to be coveted by the lover of cats, or for art alone.

But I have almost forgotten the old-time custom of, when the young ladies came from school, bringing home a "sampler," in the days before linen stamping was known or thought of. On these in needlework were alphabets, numbers, trees (such trees), dogs, and cats. Then, too, there were cats of silk and satin, in needlework, and cats in various materials; but the most curious among the young people's accomplishments was the making of tortoiseshell cats from a snail-shell, with a smaller one for a head, with either wax or bread ears, fore-legs and tail, and yellow or green beads for eyes. Droll-looking things—very. I give a drawing of one. And last, not least often, the edible cats—cats made of cheese, cats of sweet sponge-cake, cats of sugar, and once I saw a cat of jelly. In the old times of country pleasure fairs, when every one brought home gingerbread nuts and cakes as "a fairing," the gingerbread "cat in boots" was not forgotten nor left unappreciated; generally fairly good in form, and gilt over with Dutch metal, it occupied a place of honour in many a country cottage home, and, for the matter of that, also in the busy town. If good gingerbread, it was saved for many a day, or until the holiday time was ended and feasting over, and the next fair talked of.

But, after all "said and done," what a little respect, regard, and reverence is there in our mode to that of the Egyptians! They had three varieties of cats, but they were all the same to them; as their pets, as useful, beautiful, and typical, they were individually and nationally regarded, their bodies embalmed, and verses chaunted in their praise; and the image of the cat then—a thousand years ago—was a deity. What do they think of the cat now, these same though modern Egyptians? Scarcely anything. And we, who in bygone ages persecuted it, to-day give it a growing recognition as an animal both useful, beautiful, and worthy of culture.

LOVERS OF CATS

"The Turks greatly admire Cats; to them, their alluring Figure appears preferable to the Docility, Instinct, and Fidelity of the Dog. Mahomet was very partial to Cats. It is related, that being called up on some urgent Business, he preferred cutting off the Sleeve of his Robe, to waking the Cat, that lay upon it asleep. Nothing more was necessary, to bring these Animals into high Request. A Cat may even enter a Mosque; it is caressed there, as the Favourite Animal of the Prophet; while the Dog, that should dare appear in the Temples, would pollute them with his Presence, and would be punished with instant Death."8

I am indebted to the Rev. T. G. Gardner, of St. Paul's Cray, for the following from the French:

"A recluse, in the time of Gregory the Great, had it revealed to him in a vision that in the world to come he should have equal share of beatitude with that Pontiff; but this scarcely contented him, and he thought some compensation was his due, inasmuch as the Pope enjoyed immense wealth in this present life, and he himself had nothing he could call his own save one pet cat. But in another vision he was censured; his worldly detachment was not so entire as he imagined, and that Gregory would with far greater equanimity part with his vast treasures than he could part with his beloved puss."

Cats Endowed by La Belle Stewart.—One of the chief ornaments of the Court of St. James', in the reign of Charles II., was "La Belle Stewart," afterwards the Duchess of Richmond, to whom Pope alluded as the "Duchess of R." in the well-known line:

Die and endow a college or a cat.The endowment satirised by Pope has been favourably explained by Warton. She left annuities to several female friends, with the burden of maintaining some of her cats—a delicate way of providing for poor and probably proud gentlewomen, without making them feel that they owed their livelihood to her mere liberality. But possibly there may have been a kindliness of thought for both, deeming that those who were dear friends would be most likely to attend to her wishes.

Mr. Samuel Pepys had at least a gentle nature as regards animals, if he was not a lover of cats, for in his Diary occurs this note as to the Fire of London, 1666:

"September 5th.—Thence homeward having passed through

Cheapside and Newgate Market, all burned; and seen Antony Joyce's

house on fire. And took up (which I keep by me) a piece of glass

of Mercer's chapel in the street, where much more was, so melted

and buckled with the heat of the fire like parchment. I did also

see a poor cat taken out of a hole in a chimney, joining the wall

of the Exchange, with the hair all burned off its body and yet

alive."

Dr. Jortin wrote a Latin epitaph on a favourite cat:9

IMITATED IN ENGLISH"Worn out with age and dire disease, a cat, Friendly to all, save wicked mouse and rat, I'm sent at last to ford the Stygian lake, And to the infernal coast a voyage make. Me Proserpine receiv'd, and smiling said, 'Be bless'd within these mansions of the dead. Enjoy among thy velvet-footed loves, Elysian's sunny banks and shady groves.' 'But if I've well deserv'd (O gracious queen), If patient under sufferings I have been, Grant me at least one night to visit home again, Once more to see my home and mistress dear, And purr these grateful accents in her ear: "Thy faithful cat, thy poor departed slave, Still loves her mistress, e'en beyond the grave."'"

"Dr. Barker kept a Seraglio and Colony of Cats. It happened, that at the Coronation of George I. the Chair of State fell to his Share of the Spoil (as Prebendary of Westminster) which he sold to some Foreigner; when they packed it up, one of his favourite Cats was inclosed along with it; but the Doctor pursued his treasure in a boat to Gravesend and recovered her safe. When the Doctor was disgusted with the Ministry, he gave his Female Cats, the Names of the Chief Ladies about the Court; and the Male-ones, those of the Men in Power, adorning them with the Blue, Red, or Green Insignia of Ribbons, which the Persons they represented, wore."10

Daniel, in his "Rural Sports," 1813, mentions the fact that, "In one of the Ships of the Fleet, that sailed lately from Falmouth, for the West Indies, went as Passengers a Lady and her seven Lap-dogs, for the Passage of each of which, she paid Thirty Pounds, on the express Condition, that they were to dine at the Cabin-table, and lap their Wine afterwards. Yet these happy dogs do not engross the whole of their good Lady's Affection; she has also, in Jamaica, Forty Cats, and a Husband."

"The Partiality to the domestic Cat, has been thus established. Some Years since, a Lady of the name of Greggs, died at an advanced Age, in Southampton Row, London. Her fortune was Thirty Thousand Pounds, at the Time of her Decease. Credite Posteri! her Executors found in her House Eighty-six living, and Twenty-eight dead Cats. Her Mode of Interring them, was, as they died, to place them in different Boxes, which were heaped on one another in Closets, as the Dead are described by Pennant, to be in the Church of St. Giles. She had a black Female Servant—to Her she left One hundred and fifty pounds per annum to keep the Favourites, whom she left alive."11

The Chantrel family of Rottingdean seem also to be possessed with a similar kind of feeling towards cats, exhibiting no fewer than twenty-one specimens at one Cat Show, which at the time were said to represent only a small portion of their stock; these ultimately became almost too numerous, getting beyond control.

Signor Foli is a lover of cats, and has exhibited at the Crystal Palace Cat Show.

Petrarch loved his cat almost as much as he loved Laura, and when it died he had it embalmed.

Tasso addressed one of his best sonnets to his female cat.

Cardinal Wolsey had his cat placed near him on a chair while acting in his judicial capacity.

Sir I. Newton was also a lover of cats, and there is a good story told of the philosopher having two holes made in a door for his cat and her kitten to enter by—a large one for the cat, and a small one for the kitten.

Peg Woffington came to London at twenty-two years of age. After calling many times unsuccessfully at the house of John Rich, the manager of Covent Garden, she at last sent up her name. She was admitted, and found him lolling on a sofa, surrounded by twenty-seven cats of all ages.

The following is from the Echo, respecting a lady well known in her profession: "Miss Ellen Terry has a passionate fondness for cats. She will frolic for hours with her feline pets, never tiring of studying their graceful gambols. An author friend of mine told me of once reading a play to her. During the reading she posed on an immense tiger-skin, surrounded by a small army of cats. At first the playful capers of the mistress and her pets were toned down to suit the quiet situations of the play; but as the reading progressed, and the plot approached a climax, the antics of the group became so vigorous and drolly excited that my poor friend closed the MS. in despair, and abandoned himself to the unrestrained expression of his mirth, declaring that if he could write a play to equal the fun of Miss Terry and her cats, his fortune would be made."