полная версия

полная версияTen Thousand a-Year. Volume 2

"I hope, Tabby," said Mrs. Tag-rag, with subdued excitement, as they rattled homeward, "that when you're Mrs. Titmouse, you'll bring your dear husband to hear Mr. Horror? You know, we ought to be grateful to the Lord—for He has done it!"

"La, ma, how can I tell?" quoth Miss Tag-rag, petulantly. "I must go where Mr. Titmouse chooses, of course; and no doubt he'll take sittings in one of the West End churches; you know, you go where pa goes—I go where Titmouse goes! But I will come sometimes, too—if it's only to show that I'm not above it, you know. La, what a stir there will be! The three Miss Knipps—I do so hope they'll be there! I'll have your pew, ma, lined with red velvet; it will look so genteel."

"I'm not quite so sure, Tabby, though," interrupted her father, with a certain swell of manner, "that we shall, after a certain event, continue to live in these parts. There's such a thing as retiring from business, Tabby; besides, we shall nat'rally wish to be near you!"

"He's a love of a man, pa, isn't he?" interrupted Miss Tag-rag, with irrepressible excitement. Her father folded her in his arms. They could hardly believe that they had reached Satin Lodge. That respectable structure, somehow or other, now looked to the eyes of all of them shrunk into most contemptible dimensions; and they quite turned up their noses, involuntarily, on entering the little passage. What was it to the spacious and splendid residence which they had quitted? And what, in all probability, could that be to the mansion—or any one, perhaps, of the several mansions—to which Mr. Titmouse would be presently entitled, and—in his right—some one else?

Miss Tag-rag said her prayers that evening very briefly—pausing for an instant to consider, whether she might in plain terms pray that she might soon become Mrs. Titmouse; but the bare thought of such an event so excited her, that in a sort of confused whirl of delightful feeling, she suddenly jumped into bed, and slept scarce a wink all night long. Mr. and Mrs. Tag-rag talked together very fast for nearly a couple of hours, sleep long fleeing from the eyes dazzled with so splendid a vision as that which had floated before them all day. At length Mr. Tag-rag, getting tired sooner than his wife, became very sullen, and silent; and on her venturing—after a few minutes' pause—to mention some new idea which had occurred to her, he told her furiously to "hold her tongue, and let him go to sleep!" She obeyed him, and lay awake till it was broad daylight. About eight o'clock, Tag-rag, who had overslept himself, rudely roused her—imperiously telling her to "go down immediately and see about breakfast;" then he knocked gently at his daughter's door; and on her asking who it was, said in a fond way—"How are you, Mrs. T.?"

CHAPTER IV

While the brilliant success of Tittlebat Titmouse was exciting so great a sensation among the inmates of Satin Lodge and Alibi House, there were also certain quarters in the upper regions of society, in which it produced a considerable commotion, and where it was contemplated with feelings of intense interest; nor without reason. For indeed to you, reflecting reader, much pondering men and manners, and observing the influence of great wealth, especially when suddenly and unexpectedly acquired, upon all classes of mankind—it would appear passing strange that so prodigious an event as that of an accession to a fortune of ten thousand a-year, and a large accumulation of money besides, could be looked on with indifference in those regions where MONEY

"Is like the air they breathe—if they have it not they die;"in whose absence, all their "honor, love, obedience, troops of friends," disappear like snow under sunshine; the edifice of pomp, luxury, and magnificence that "rose like an exhalation," so disappears—

"And, like an insubstantial pageant faded,Leaves not a rack behind."Take away money, and that which raised its delicate and pampered possessors above the common condition of mankind—that of privation and incessant labor and anxiety—into one entirely artificial, engendering totally new wants and desires, is gone, all gone; and its occupants suddenly fall, as it were, through a highly rarefied atmosphere, breathless and dismayed, into contact with the chilling exigencies of life, of which till then they had only heard and read, sometimes with a kind of morbid sympathy; as we hear and read of a foreign country, not stirring the while from our snug homes, by whose comfortable and luxurious firesides we read of the frightful palsying cold of the polar regions, and for a moment sigh over and shudder at the condition of their miserable inhabitants, as vividly pictured to us by adventurous travellers.

If the reader had reverently cast his eye over the pages of that glittering centre of aristocratic literature, and inexhaustible solace against the ennui of a wet day—I mean Debrett's Peerage, his attention could not have failed to be riveted, among a galaxy of brilliant but minor stars, by the radiance of one transcendent constellation.

Behold; hush; tremble!

"Augustus Mortimer Plantagenet Fitz-Urse, Earl of Dreddlington, Viscount Fitz-Urse, and Baron Drelincourt; Knight of the Golden Fleece; G. C. B., D. C. L., F. C. S., F. P. S., &c., &c., &c.; Lieutenant-General in the army, Colonel of the 37th regiment of light dragoons; Lord Lieutenant of –shire; elder brother of the Trinity House; formerly Lord Steward of the Household; born the 31st of March, 17—; succeeded his father, Percy Constantine Fitz-Urse, as fifth Earl, and twentieth in the Barony, January 10th, 17—; married, April 1, 17—, the Right Hon. Lady Philippa Emmeline Blanche Macspleuchan, daughter of Archibald, ninth Duke of Tantallan, K. T., and has issue an only child,

"Cecilia Philippa Leopoldina Plantagenet, born June 10, 17—.

"Town residence, Grosvenor Square.

"Seats, Gruneaghoolaghan Castle, Galway; Tre-ardevoraveor Manor, Cornwall; Llmryllwcrwpllglly Abbey, N. Wales; Tully-clachanach Palace, N. Britain; Poppleton Hall, Hertfordshire.

"Earldom, by patent, 1667; – Barony, by writ of summons, 12th Hen. II."

Now, as to the above tremendous list of seats and residences, be it observed that the existence of two of them, viz. Grosvenor Square and Poppleton Hall, was tolerably well ascertained by the residence of the august proprietor of them, and the expenditure therein of his princely revenue of £5,000 a-year. The existence of the remaining ones, however, the names of which the diligent chronicler has preserved with such scrupulous accuracy, had become somewhat problematical since the era of the civil wars, and the physical derangement of the surface of the earth in those parts, which one may conceive to have taken place11 consequent upon those events; those imposing feudal residences having been originally erected in positions so carefully selected with a view to their security against aggression, as to have become totally inaccessible—and indeed unknown, to the present inglorious and degenerate race, no longer animated by the spirit of chivalry and adventure.

[I have now recovered my breath, after my bold flight into the resplendent regions of aristocracy; but my eyes are still dazzled.]

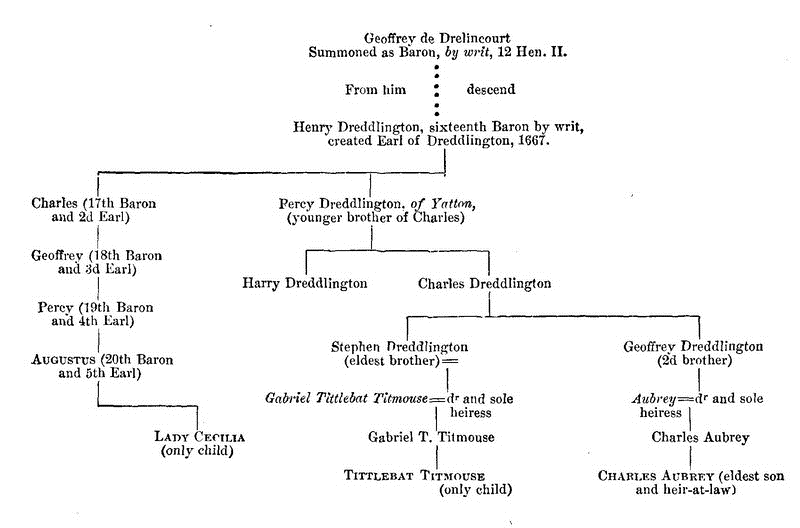

The reader may by this time have got an intimation that Tittlebat Titmouse, in a madder freak of Fortune than any which her incomprehensible Ladyship hath hitherto exhibited in the pages of this history, is far on his way towards a dizzy pitch of elevation,—viz. that he has now, owing to the verdict of the Yorkshire jury, taken the place of Mr. Aubrey, and become heir-expectant to the oldest barony in the kingdom—between it and him only one old peer, and his sole child, an unmarried daughter, intervening. Behold the thing demonstrated to your very eye, in the Pedigree on the next page, which is only our former one12 a little extended.

From this I think it will appear, that on the death of Augustus, fifth earl and twentieth baron, with no other issue than Lady Cecilia, the earldom being then extinct, the barony would descend upon the Lady Cecilia; and that, in the event of her dying without issue in the lifetime of her father, Tittlebat Titmouse would, on the earl's death without other lawful issue, become Lord Drelincourt, twenty-first in the barony! and in the event of her dying without issue, after her father's death, Tittlebat Titmouse would become the twenty-second Lord Drelincourt; one or other of which two splendid positions, but for the enterprising agency of Messrs. Quirk, Gammon, and Snap, would have been occupied by Charles Aubrey, Esq.;—on considering all which, one cannot but remember a saying of an ancient poet, who seems to have kept as keen an eye upon the unaccountable frolics of the goddess Fortune, as this history shows that I have. 'Tis a passage which any little schoolboy will translate to his mother or his sisters—

——"Hinc apicem rapaxFortuna cum stridore acutoSustulit, hic posuisse gaudet."13At the time of which I am writing, the Earl of Dreddlington was about sixty-seven years old; and he would have realized the idea of an incarnation of the sublimest PRIDE. He was of rather a slight make, and, though of a tolerably advanced age, stood as straight as an arrow. His hair was glossy, and white as snow: his features were of an aristocratic cast; their expression was severe and haughty; and I am compelled to say that there was scarce a trace of intellect perceptible in them. His manner and demeanor were cold, imperturbable, inaccessible; wherever he went—so to speak—he radiated cold. Comparative poverty had embittered his spirit, as his lofty birth and ancient descent had generated the pride I have spoken of. With what calm and supreme self-satisfaction did he look down upon all lower in the peerage than himself! And as for a newly-created peer, he looked at such a being with ineffable disdain. Among his few equals he was affable enough; and among his inferiors he exhibited an insupportable appearance of condescension—one which excited a wise man's smile of pity and contempt, and a fool's anger—both, however, equally nought to the Earl of Dreddlington!—If any one could have ventured upon a post mortem examination of so august a structure as the earl's carcass, his heart would probably have been found to be of the size of a pea, and his brain very soft and flabby; both, however, equal to the small occasions which, from time to time, called for the exercise of their functions. The former was occupied almost exclusively by two feelings—love of himself and of his daughter, (because upon her would descend his barony;) the latter exhibited its powers (supposing the brain to be the seat of the mind) in mastering the military details requisite for nominal soldiership; the game of whist; the routine of petty business in the House of Lords; and the etiquette of the court. One branch of useful knowledge by the way he had, however, completely mastered—that which is so ably condensed in Debrett; and he became a sort of oracle in such matters. As for his politics, he professed Whig principles—and was, indeed, a bitter though quiet partisan. In attendance to his senatorial duties, he practised an exemplary punctuality; was always to be found in the House at its sitting and rising; and never once, on any occasion, great or small, voted against his party. He had never been heard to speak in a full House; first, because he never could summon nerve enough for the purpose; secondly, because he never had anything to say; and lastly, lest he should compromise his dignity, and destroy the prestige of his position, by not speaking better than any one present. His services were not, however, entirely overlooked; for, on his party coming into office for a few weeks, (they knew it could be for no longer a time,) they made him Lord Steward of the Household; which was thenceforward an epoch to which he referred every event of his life, great and small. The great object of his ambition, ever since he had been of an age to form large and comprehensive views of action and conduct, to conceive superior designs, and to achieve distinction among mankind—was, to obtain a step in the peerage; for considering the antiquity of his family, and his ample, nay, superfluous pecuniary means—so much more than adequate to support his present double dignity of earl and baron—he thought it but a reasonable return for his eminent political services, to confer upon him the honor which he coveted. But his anxiety on this point had been recently increased a thousand-fold by one circumstance. A gentleman who held an honorable and lucrative official situation in the House of Lords, and who never had treated the Earl of Dreddlington with that profound obsequiousness which the earl conceived to be his due—but, on the contrary, had presumed to consider himself a man, and an Englishman, equally with the earl—had, a short time before, succeeded in establishing his title to an earldom which had long been dormant, and was, alas, of creation earlier than that of Dreddlington. The Earl of Dreddlington took this untoward circumstance so much to heart, that for some months afterwards he appeared to be in a decline; always experiencing a dreadful inward spasm whenever the Earl of Fitzwalter made his appearance in the House. For this sad state of things there was plainly but one remedy—a Marquisate—at which the earl gazed with the wistful eye of an old and feeble ape at a cocoa-nut, just above his reach, and which he beholds at length grasped and carried off by some nimbler and younger rival.

Among all the weighty cares and anxieties of this life, however, I must do the earl the justice to say, that he did not neglect the concerns of hereafter—the solemn realities of that Future revealed to us in the Scriptures. To his enlightened and comprehensive view of the state of things around him, it was evident that the Author of the world had decreed the existence of regular gradations of society. The following lines, quoted one night in the House by the leader of his party, had infinitely delighted the earl—

"Oh, where DEGREE is shaken,Which is the ladder to all high designs,The enterprise is sick!Take but DEGREE away—untune that string,And, hark! what discord follows! each thing meets,In mere oppugnancy!"14When the earl discovered that this was the production of Shakespeare he conceived a great respect for that writer, and purchased a copy of his works, and had them splendidly bound. They were fated never to be opened, however, except at that one place where the famous passage in question was to be found. How great was the honor thus conferred upon the plebeian poet, to stand amid a collection of royal and noble authors, to whose productions, and those in elucidation and praise of them, the earl's splendid-looking library had till then been confined!—Since, thought the earl, such is clearly the order of Providence in this world, why should it not be so in the next? He felt certain that then there would be found corresponding differences and degrees, in analogy to the differences and degrees existing upon earth; and with this view had read and endeavored to comprehend the first page or two of a very dry but learned book—Butler's Analogy—lent him by a deceased kinsman—a bishop. This consolatory conclusion of the earl's was greatly strengthened by a passage of Scripture, from which he had once heard the aforesaid bishop preach—"In my Father's house are MANY MANSIONS; if it had not been so, I would have told you." On grounds such as these, after much conversation with several old brother peers of his own rank, he and they—those wise and good men—came to the conclusion that there was no real ground for apprehending so grievous a misfortune as the huddling together hereafter of the great and small into one miscellaneous and ill-assorted assemblage; but that the rules of precedence, in all their strictness, as being founded in the nature of things, would meet with an exact observance, so that every one should be ultimately and eternally happy—in the company of his equals. The Earl of Dreddlington would have, in fact, as soon supposed, with the deluded Indian, that in his voyage to the next world—

"His faithful dog should bear him company;"as that his Lordship should be doomed to participate the same regions of heaven with any of his domestics; unless, indeed, by some, in his view, not improbable dispensation, it should form an ingredient in their cup of happiness in the next world, there to perform those offices—or analogous ones—for their old masters, which they had performed upon earth. As the earl grew older, these just, and rational, and Scriptural views, became clearer, and his faith firmer. Indeed, it might be said that he was in a manner ripening for immortality—for which his noble and lofty nature, he secretly felt, was fitter, and more likely to be in its element, than it could possibly be in this dull, degraded, and confused world. He knew that there his sufferings in this inferior stage of existence would be richly recompensed,—for sufferings indeed he had, though secret, arising from the scanty means which had been allotted to him for the purpose of maintaining the exalted rank to which it had pleased God to call him. The long series of exquisite mortifications and pinching privations arising from this inadequacy of means, had, however, the earl doubted not, been designed by Providence as a trial of his constancy, and from which he would, in due time, issue like thrice-refined gold. Then also would doubtless be remembered in his favor the innumerable instances of his condescension in mingling, in the most open and courteous manner, with those who were unquestionably his inferiors, sacrificing his own feelings of lofty and fastidious exclusiveness, and endeavoring to advance the interests, and as far as influence and example went, polish and refine the manners of the lower orders of society. Such is an outline—alas, how faint and imperfect!—of the character of this great and good man, the Earl of Dreddlington. As for his domestic and family circumstances, he had been a widower for some fifteen years, his countess having brought him but one child, Lady Cecilia Philippa Leopoldina Plantagenet, who was, in almost all respects, the counterpart of her illustrious father. She resembled him not a little in feature, only that she partook of the plainness of her mother. Her complexion was delicately fair; but her features had no other expression than that of a languid hauteur. Her upper eyelids drooped as if she could hardly keep them open; the upper jaw projected considerably over the under one; and her front teeth were prominent and exposed. Frigid and inanimate, she seemed to take but little interest in anything on earth. In person, she was of average height, of slender and well-proportioned figure, and an erect and graceful carriage, only that she had a habit of throwing her head a little backward, which gave her a singularly disdainful appearance. She had reached her twenty-seventh year without having had an eligible offer of marriage, though she would be the possessor of a barony in her own right, and £5,000 a-year; a circumstance which, it may be believed, not a little embittered her. She inherited her father's pride in all its plenitude. You should have seen the haughty couple sitting silently side by side in the old-fashioned yellow family chariot, as they drove round the crowded park, returning the salutations of those they met in the slightest manner possible! A glimpse of them at such a moment would have given you a far more just and lively notion of their real character, than the most anxious and labored description of mine.

Ever since the first Earl of Dreddlington had, through a bitter pique conceived against his eldest son, the second earl, diverted the principal family revenues to the younger branch, leaving the title to be supported by only £5,000 a-year, there had been a complete estrangement between the elder and the younger—the titled and the moneyed—branches of the family. On Mr. Aubrey's attaining his majority, however, the present earl sanctioned overtures being made towards a reconciliation, being of opinion that Mr. Aubrey and Lady Cecilia might, by intermarriage, effect a happy reunion of family interests; an object, this, which had long lain nearer his heart than any other upon earth, till, in fact, it became a kind of passion. Actuated by such considerations, he had done more to conciliate Mr. Aubrey than he had ever done towards any one on earth. It was, however, in vain. Mr. Aubrey's first delinquency was an unqualified adoption of Tory principles. Now all the Dreddlingtons, from time whereof the memory of man runneth not to the contrary, had been firm unflinching Tories, till the distinguished father of the present earl quietly walked over, one day, to the other side of the House of Lords, completely fascinated by a bit of ribbon which the minister held up before him; and ere he had sat in that wonder-working region, the ministerial side of the House, twenty-four hours, he discovered that the true signification of Tory, was bigot—and of Whig, patriot; and he stuck to that version till it transformed him into a GOLD STICK, in which capacity he died; having repeatedly and solemnly impressed upon his son, the necessity and advantage of taking the same view of public affairs, that so he might arrive at similar results. And in the way in which he had been trained up, most religiously had gone the earl; and see the result: he, also, had attained to eminent and responsible office—to wit, that of Lord Steward of the Household. Now, things standing thus—how could the earl so compromise his principles, and indirectly injure his party, as by suffering his daughter to marry a Tory? Great grief and vexation of spirit did this matter, therefore, occasion to that excellent nobleman. But, secondly, Aubrey not only declined to marry his cousin, but clinched his refusal, and sealed his final exclusion from the dawning good opinion and affections of the earl, by marrying, as hath been seen, some one else—Miss St. Clair. Thenceforth there was a great gulf between the Earl of Dreddlington and the Aubreys. Whenever they happened to meet, the earl greeted him with an elaborate bow, and a petrifying smile; but for the last seven years not one syllable had passed between them. As for Mr. Aubrey, he had never been otherwise than amused at the eccentric airs of his magnificent kinsman.—Now, was it not a hard thing for the earl to bear—namely, the prospect there was that his barony and estates might devolve upon this same Aubrey, or his issue? for Lady Cecilia, alas! enjoyed but precarious health, and her chances of marrying seemed daily diminishing. This was a thorn in the poor earl's flesh; a source of constant worry to him, sleeping and waking; and proud as he was, and with such good reason, he would have gone down on his knees and prayed to Heaven to avert so direful a calamity—to see his daughter married—and with a prospect of perpetuating upon the earth the sublime race of the Dreddlingtons.

Such being the relative position of Mr. Aubrey, and the Earl of Dreddlington, at the time when this history opens, it is easy for the reader to imagine the lively interest with which the earl first heard of the tidings that a stranger had set up a title to the whole of the Yatton estates; and the silent but profound anxiety with which he continued to regard the progress of the affair. He obtained, from time to time, by means of confidential inquiries instituted by his solicitor, a general notion of the nature of the new claimant's pretensions; but with a due degree of delicacy towards his unfortunate kinsman, his Lordship studiously concealed the interest he felt in so important a family question as the succession to the Yatton property. The earl and his daughter were exceedingly anxious to see the claimant; and when he heard that that claimant was a gentleman of "decided Whig principles"—the earl was very near setting it down as a sort of special interference of Providence in his favor; and one that, in the natural order of things, would lead to the accomplishment of his other wishes. Who could say that, before a twelvemonth had passed over, the two branches of the family might not be in a fair way of being reunited? And that thus, among other incidents, the earl would be invested with the virtual patronage of the borough of Yatton, and, in the event of their return to power, his claim upon his party for his long-coveted marquisate rendered irresistible? He had gone to the Continent shortly before the trial of the ejectment at York; and did not return till a day or two after the Court of King's Bench had solemnly declared the validity of the plaintiff's title to the Yatton property, and consequently established his contingent right of succession to the barony of Drelincourt. Of this event a lengthened account was given in one of the Yorkshire papers which fell under the earl's eye the day after his arrival from abroad; and to the report of the decision of the question of law, was appended the following paragraph:—