полная версия

полная версияThe Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries

Rhetoric and oratory was studied very assiduously. Cicero was the favorite reading of the great preachers of the time, and we find the court preachers of St. Louis, Étienne de Bourbon, Elinand, Guillaume de Perrault and others appealing to his precepts as the infallible guide to oratory. Quintilian was not neglected, however, and Symmachus and Sidonius Apollinaris were also faithfully studied. If we turn to the speeches that are incorporated in the epics, as, for instance, the Cid, or in some of the historians, as Villehardouin, we have definite evidence of the thorough command of the writers of the time over the forms of oratory. M. Paullin Paris, the authority in our time on the literature of the Thirteenth Century, quotes a passage from Villehardouin in which Canon de Bethune speaks in the name of the French chiefs of the Fourth Crusade to the Emperors Isaac and Alexis Comnenus. M. Paris does not hesitate to declare that the passage is equal to many of the same kind that have been much admired in the classic authors. It has the force, the finish and the compression of Thucydides.

XVII. GREAT BEGINNINGS IN ENGLISH LITERATURE

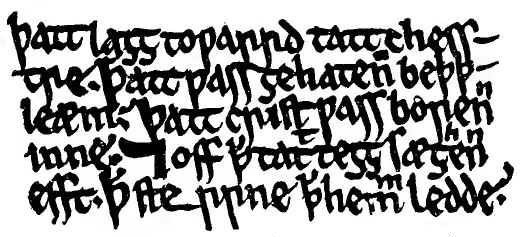

Only the fact that this work was getting beyond the number of printed pages determined for it in the first edition prevented the insertion of a chapter especially devoted to the great beginnings of English literature in the Thirteenth Century. The most important contributions to Early English were made at this period. The Ormulum and Layamon's Brut, both written probably during the first decade of the Thirteenth Century, have become familiar to all students of Old English. Mr. Gollancz goes so far as to say that "The Ormulum is perhaps the most valuable document we possess for the history of English sound. Orm was a purist in orthography as well as in vocabulary, and may fittingly be described as the first of English phoneticians."

MANUSCRIPT OF ORMULUM (THIRTEENTH CENTURY)

Of Layamon, Garnett said in his "English Literature" (Garnett and Gosse): "It would have sufficed for the fame of Layamon had he been no more than the first minstrel to celebrate Arthur in English song, but his own pretensions as a poet are by no means inconsiderate. He is everywhere vigorous and graphic, and improved upon his predecessor, Wace, alike by his additions and expansions, and by his more spiritual handling of the subjects common to both." Even more important in the history of language than these is The Ancren Riwle (The Anchorites' Rule). This was probably written by Richard Poore, Bishop of Salisbury, for three Cistercian nuns. Its place in English literature may be judged from a quotation or two with regard to it. Mr. Kington-Oliphant says: "The Ancren Riwle is the forerunner of a wondrous change in our speech. More than anything else written outside the Danelagh, that piece has influenced our standard English." Garnett says: "The Ancren Riwle is a work of great literary merit and, in spite of its linguistic innovations, most of which have established themselves, well deserves to be described as 'one of the most perfect models of simple eloquent prose in our language.'"

The religious poetry of the time is not behind the great prose of The Ancren Riwle, and one of them, the Luve Ron (Love Song) of Thomas de Hales, is very akin to the spirit of that work, and has been well described as "a contemplative lyric of the simplest, noblest mold." Garnett says: "The reflections are such as are common to all who have in all ages pleaded for the higher life under whatsoever form, and deplored the frailty and transitoriness of man's earthly estate. Two stanzas on the latter theme as expressed in a modernized version might almost pass for Villon's:—

"Paris and Helen, where are they, Fairest in beauty, bright to view? Amadas, Tristrem, Ideine, yea Isold, that lived with love so true? And Caesar, rich in power and sway, Hector the strong, with might to do? All glided from earth's realm away, Like shaft that from the bow-string flew. "It is as if they ne'er were here. Their wondrous woes have been a' told, That it is sorrow but to hear; How anguish killed them sevenfold, And how with dole their lives were drear; Now is their heat all turned to cold. Thus this world gives false hope, false fear; A fool, who in her strength is bold."XVIII. GREAT ORIGINS IN MUSIC

In the chapter on the Great Latin Hymns a few words were said about one phase of the important musical development in the Thirteenth Century, that of plain chant. In that simple mode the musicians of the Thirteenth Century succeeded in reaching a climax of expression of human feeling in such chants as the Exultet and the Lamentation that has never been surpassed. Something was also said about the origin of part music, but so little that it might easily be thought that in this the century lagged far behind its achievements in other departments. M, Pierre Aubry has recently published (1909) Cent Motets du XIIIe Siècle in three volumes. His first volume contains a photographic reproduction of the manuscript of Bamberg from which the hundred musical modes are secured, the second a transcription in modern musical notation of the old music, and the third volume studies and commentaries on the music and the times. If anything were needed to show how utterly ignorant we have been of the interests and artistic achievements of the Middle Ages, it is this book of M. Aubry.

Victor Hugo said that music dates from the Sixteenth Century, and it has been quite the custom, even for people who thought they knew something about music, to declare that we had no remains of any music before the Sixteenth Century worth while talking about. Ancient music is probably lost to us forever, but M. Aubry has shown conclusively that we have abundant remains to show us that the musicians of the Thirteenth Century devoted themselves to their art with as great success as their rivals in the other Gothic arts and, indeed, they thought that they had nearly exhausted its possibilities and tried to make a science of it. By their supposedly scientific rules they succeeded in binding music so firmly as to bring about its obscuration in succeeding centuries. This is, however, the old story of what has happened in every art whenever genius succeeds in finding a great mode of expression. A formula is evolved which often binds expression so rigorously as to prevent natural development.

XIX. A CHAPTER ON MANNERS

Whatever the people of the Middle Ages may have been in morals, their manners are supposed to have been about as lacking in refinement as possible. As for nearly everything else, however, this impression is utterly false, and is due to the assumption that because we are better-mannered than the generations of a century or two ago, therefore we must be almost infinitely in advance, in the same respect, of the people of seven centuries ago. There are ups and downs in manners, however, as there are in education, and the beginnings of the formal setting forth of modern manners are, like everything else modern, to be found in the Thirteenth Century. About the year 1215 Thomasin Zerklaere wrote in German a rather lengthy treatise, Der Wälsche Gast, on manners. It contains most of the details of polite conduct that have been accepted in later times. Not long afterwards, John Garland, an Oxford man who had lived in France for many years, wrote a book on manners for English young men. He meant this to be a supplement to Dionysius Cato's treatise, written probably in the Fourth Century in Latin, which was concerned more with morals than manners and had been very popular during the Middle Ages. Garland's book was the first of a series of such treatises on manners which appeared in England at the close of the Middle Ages. Many of them have been recently republished, and are a revelation of the development of manners among our English forefathers. The book is usually alluded to in literature as Liber Faceti, or as Facet; the full title was, "The Book of the Polite Man, Teaching Manners for Men, Especially for Boys, as a Supplement to those which were Omitted by the Most Moral Cato." The "Romance of the Rose" has, of course, many references to manners which show us how courtesy was cultivated in France. In Italy, Dante's teacher, Bruneto Latini, published his "Tesoretto," which treats of manners, and which was soon followed by a number of similar treatises in Italian. In a word, we must look to the Thirteenth Century for the origin, or at least the definite acceptance, of most of those conventions which make for kindly courtesy among men, and have made possible human society and friendly intercourse in our modern sense of those words.

We are prone to think that refinement in table manners is a matter of distinctly modern times. In "The Babees' Book," which is one of the oldest books of English manners, the date of which in its present form is about the middle of the Fourteenth Century, many of our rules of politeness at table are anticipated. This book is usually looked upon as a compilation from preceding times, and the original of it is supposed to be from the preceding century. A few quotations from it will show how closely it resembles our own instructions to children:

"Thou shalt not laugh nor speak nothing While thy mouth be full of meat or drink; Nor sup thou not with great sounding Neither pottage nor other thing. At meat cleanse not thy teeth, nor pick With knife or straw or wand or stick. While thou holdest meat in mouth, beware To drink; that is an unhonest chare; And also physic forbids it quite. Also eschew, without strife. To foul the board cloth with thy knife. Nor blow not on thy drink or meat, Neither for cold, neither for heat. Nor bear with meat thy knife to mouth. Whether thou be set by strong or couth. Lean not on elbow at thy meat, Neither for cold nor for heat. Dip not thy thumb thy drink into; Thou art uncourteous if thou it do. In salt-cellar if thou put Or fish or flesh that men see it, That is a vice, as men me tells; And great wonder it would be else."The directions, "how to behave thyself in talking with any man," in one of these old books, are very minute and specific:—

"If a man demand a question of thee. In thine answer making be not too hasty; Weigh well his words, the case understand Ere an answer to make thou take in hand; Else may he judge in thee little wit, To answer to a thing and not hear it. Suffer his tale whole out to be told. Then speak thou mayst, and not be controlled; In audible voice thy words do thou utter, Not high nor low, but using a measure. Thy words see that thou pronounce plaine. And that they spoken be not in vain; In uttering whereon keep thou an order, Thy matter thereby thou shalt much forder Which order if thou do not observe. From the purpose needs must thou swerve."XX. TEXTILE WORK OF THE CENTURY

A special chapter might easily have been written on the making of fine cloths of various kinds, most of which reached their highest perfection in the Thirteenth Century. Velvet, for instance, is mentioned for the first time in England in 1295, but existed earlier on the continent, and cut velvets with elaborate patterns were made in Genoa exactly as we know finished velvet now. Baudekin or Baldichin, a very costly textile of gold and silk largely used in altar coverings and hangings, came to very high perfection in this century also. The canopy for the Blessed Sacrament is, because of its manufacture from this cloth, still called in Italy a baldichino. Chaucer in the next century tells how the streets in royal processions were "hanged with cloth of gold and not with serge." Satin also was first manufactured very probably in the Thirteenth Century. It is first mentioned in England about the middle of the Fourteenth Century, when Bishop Grandison made a gift of choice satins to Exeter Cathedral. The word satin, however, is derived from the silks of the Mediterranean, called by the Italians seta and by the Spanish seda, and the art of making it was brought to perfection during the preceding century.

The art of making textiles ornamented with elaborate designs of animal forms and of floral ornaments reached its highest perfection in the Thirteenth Century. In one of the Chronicles we learn that in 1295 St. Paul's in London owned a hanging "patterned with wheels and two-headed birds." We have accounts of such elaborate textile ornamentation as peacocks, lions, griffins and the like. Almeria in Andalusia was a rich city in the Thirteenth Century, noted for its manufactures of textiles. A historian of the period writes: "Christians of all nations came to its port to buy and sell. Then they traveled to other parts of the interior of the country, where they loaded their vessels with such goods as they wanted. Costly silken robes of the brightest colors are manufactured in Almeria." Marco-Polo says of the Persians that, when he passed through that country (end of the Thirteenth Century), "there are excellent artificers in the city who make wonderful things in gold, silk and embroidery. The women make excellent needlework in silk with all sorts of creatures very admirably wrought therein." He also reports the King of Tartary as wearing on his birthday a most precious garment of gold, and tells of the girdles of gold and silver, with pearls and ornaments of great price on them.

Unfortunately English embroidery fell off very greatly at the time of the Wars of the Roses. These wars constitute the main reason why nearly every form of intellectual accomplishment and artistic achievement went into decadence during the Fourteenth Century, from which they were only just emerging when the so-called reformation, with its confiscation of monastic property, and its destruction of monastic life, came to ruin schools of all kinds, and, above all, those in which the arts and crafts had been taught so successfully. France at the end of the Thirteenth Century saw a similar rise to excellence of textile and embroidery work. In 1299 there is an allusion to one Clément le Brodeur who furnished a magnificent cope for the Count of Artois. In 1316 a beautifully decorated set of hangings was made for the Queen by Gautier de Poulleigny. There are other references to work done in the early part of the Fourteenth Century, which serve to show the height which art had reached in this mode during the Thirteenth Century. In Ireland, while the finer work had its due place, the making of woolens was the specialty, and the dyeing of woolen cloth made the Irish famous and brought many travelers from the continent to learn the secret.

The work done in England in embroidery attracted the attention of the world. English needlework became a proverb. In the body of the book I mentioned the cope of Ascoli, but there were many such beautiful garments. The Syon cope is, in the opinion of Miss Addison, author of "Arts and Crafts in the Middle Ages," the most conspicuous example of the medieval embroiderers' art. It was made by nuns about the middle of the Thirteenth Century, that is, just about the same time as the cope of Ascoli, but in a convent near Coventry. According to Miss Addison "it is solid stitchery on a canvas ground, wrought about with divers colors' on green. The design is laid out in a series of interlacing square forms, with rounded and barbed sides and corners. In each of these is a figure or a Scriptural scene. The orphreys, or straight borders, which go down on both fronts of the cope, are decorated with heraldic charges. Much of the embroidery is raised, and wrought in the stitch known as Opus Anglicanum. The effect was produced by pressing a heated metal knob into the work at such points as were to be raised. The real embroidery was executed on a flat surface, and then bossed up by this means until it looked like bas-relief. The stitches in every part run in zig-zags, the vestments, and even the nimbi about the heads, are all executed with the stitches slanting in one direction, from the center of the cope outward, without consideration of the positions of the figures. Each face is worked in circular progression outward from the center, as well. The interlaces are of crimson, and look well on the green ground. The wheeled cherubim is well developed in the design of this famous cope, and is a pleasing decorative bit of archaic ecclesiasticism. In the central design of the Crucifixion, the figure of the Lord is rendered in silver on a gold ground."

XXI. GLASS-MAKING

A chapter might well have been devoted to Thirteenth Century glass-making quite apart from the stained glass of the cathedral windows. All over Europe some of the most wonderful specimens of colored glass we possess were made in the Thirteenth Century. Recently Mr. Frederick Rolfe has looked up for me Venetian glass, of the three centuries, the Twelfth, the Thirteenth and the Fourteenth. He says Twelfth Century glass is small in form, simple and ignorant in model, excessively rich and brilliant in colors; the artist evidently had no ideal, but the Byzantine of jewels and emeralds.

"Thirteenth Century glass is absolutely different. The specimens are pretty. The work of the Beroviero family is large and splendid in form, exquisite and sometimes elaborate in model, mostly crystal glass reticently studded with tiny colored gem-like knobs. There are also fragments of two windows pieced together, and missing parts filled with the best which modern Murano can do. These show the celebrated Beroviero Ruby glass (secret lost) of marvelous depth and brilliancy in comparison with which the modern work is merely watery. The ancient is just like a decanter of port-wine.

"Fourteenth Century returns to the wriggling ideal and exiguous form of the Twelfth Century, and fails woefully in brilliance of color. It is small and dull and undistinguished. One may find out what war or pest afflicted Murano at this epoch to explain the singular degradation."

This same curious degradation took place in the manufacture of most art objects during the Fourteenth Century. One would feel in Mr. Rolfe's words like looking for some physical cause for it. The decadence is so universal, however, that it seems not unlikely that it follows some little known human law, according to which, after man has reached a certain perfection of expression in an art or craft, there comes, in the striving after originality yet variety, an overbalancing of the judgment, a vitiation of the taste in the very luxuriance of beauty discovered that leads to decay. It is the very contradiction of the supposed progress of mankind through evolution, but it is illustrated in many phases of human history and, above all, the history of art, letters, education and the arts and crafts.

XXII. INVENTIONS

Most people are sure to think that, at least in the matter of inventions, ours is the only time worth considering. The people of the Thirteenth Century, however, made many wonderful inventions and adaptations of mechanical principles, as well as many ingenious appliances. Their faculty of invention was mainly devoted to work in other departments besides that of mechanics. They were inventors of designs in architecture, in decoration, in furnishings, in textiles, and in the beautiful things of life generally. Their inventiveness in the arts and crafts was especially admirable and, indeed, has been fruitful in our time, since, with the reawakening in this matter, we have gone back to imitate their designs. Good authorities declare these to be endless in number and variety. Such mechanical inventions as were needed for the building of their great cathedrals, their municipal buildings, abbeys, castles, piers, bridges and the like were admirably worked out. Necessity is the mother of invention, and whenever needs asserted themselves, these old generations responded to them, very successfully. There are, however, a number of inventions that would attract attention even, in the modern time for their practical usefulness and ingenuity. With the growth of the universities writing became much more common, textbooks were needed, and so paper was invented. With the increase of reading, to replace teaching by hearing, spectacles were invented. Time became more precious, clocks were greatly improved, and we hear of the invention of something like an alarm clock, an apparatus which, after a fixed number of hours, woke the monk of the abbey whose duty it was to arouse the others. Organs for churches were greatly improved, bells were perfected, and everything else in connection with the churches so well fashioned that we still use them in their Thirteenth Century forms. Gunpowder was not invented, but a great many new uses were found for it, and Roger Bacon even suggested, as I have said, that sometime explosives would enable boats to move by sea without sails or oars, or carriages to move on land without horses or men. Roger Bacon even suggested the possibility of airships, described how one might be made, the wings of which would be worked by a windlass, and thought that he could make it. His friend and pupil, Peregrinus, invented the double pivoted compass, and, as the first perpetual-motion faddist, described how he would set about making a magnetic engine that he thought would run forever. When we recall how much they accomplished mechanically in the construction of buildings, it becomes evident that any mechanical problem that these generations wanted solved they succeeded in solving very well. What they have left us as inventions are among the most useful appliances that we have. Without paper and without spectacles, the intellectual world would be in a sad case, indeed. Many of the secrets of their inventions in the arts and crafts have been lost, and, in spite of all our study, we have not succeeded in rediscovering them.

XXIII. INDUSTRY AND TRADE

We are rather inclined to think that large organizations of industry and trade were reserved for comparatively modern times. To think so, however, is to forget the place occupied by the monasteries and convents in the olden time. We have heard much of the lazy monks, but only from those who know nothing at all about them. Idleness in the monasteries was one of the accusations made by the commission set to furnish evidence to Henry VIII. on which he might suppress the monasteries, but every modern historian has rejected the findings of that commission as false. Many forms of manufacture were carried on in the monasteries and convents. They were the principal bookmakers and bookbinders. To a great extent they were the manufacturers of art fabrics and arts-and-crafts work intended for church use, but also for the decoration of luxurious private apartments. Most of us have known something of all this finer work, but not that they had much to do with cruder industries also. They were millers, cloth-makers, brush- and broom-makers, shoemakers for themselves and their tenantry; knitting was done in the convents, and all the finer fancy work. A recent meeting of the Institute of Mining Engineers in England brought out some discussion of coal mining in connection with the early history of the coal mines in England. The records of many of the English monasteries show that in early times the monks knew the value of coal, and used it rather freely. They also mined it for others. The monks at Tynemouth are known to have been mining coal on the Manor of Tynemouth in 1269, and shipping it to a distance. At Durham and at Finchale Abbey they were doing this also about the same time. It would require special study to bring out the interesting details, but there is abundant material not alone for a chapter, but for a volume on the industries of the Thirteenth Century, which, like the education and the literature and the culture of the time, we have thought undeveloped, because we knew nothing of them.

The relation of the monasteries to trade, domestic and foreign, is very well brought out in a paragraph of Mr. Ralph Adams Cram's book on "The Ruined Abbeys of Great Britain" (New York, The Churchman Co., 1905), in which he describes the remains at Beaulieu, which show the place of that monastery, not by any means one of the most important in England, in trade. For the benefit of their tenantry others had done even more.