полная версия

полная версияThe Campaign of Königgrätz

Hozier, Adams, Derrécagaix and (above all) the Prussian Official History of the Campaign of 1866, claim that the best move of Von Benedek would have been against the Crown Prince. If we consider the successful passage of the defiles by the Second Army as a thing to be taken for granted in Von Benedek’s plan of campaign, there can be no doubt that the Austrian commander should have turned his attention to the Crown Prince, and that he should have attacked him with six corps, as soon as the Prussians debouched from the defiles of Trautenau and Nachod. The line of action here suggested as one that would probably have resulted in Austrian success, is based entirely on the condition that the Second Army should be contained at the defiles, by a force strongly entrenched after the American manner of 1864-5; a condition not considered by the eminent authorities mentioned above. After the Crown Prince had safely passed the defiles, Von Benedek had either to attack him or fall back. The time for a successful move against Frederick Charles had passed.

Von Benedek had carefully planned an invasion of Prussia. Had he been able to carry the war into that country, his operations might, perhaps, have been admirable; but when the superior preparation of the Prussians enabled them to take the initiative, he seems to have been incapable of throwing aside his old plans and promptly adopting new ones suited to the altered condition of affairs. Von Benedek was a good tactician and a stubborn fighter; but when he told the Emperor “Your Majesty, I am no strategist,” and wished to decline the command of the army, he showed a power of correct self-analysis equal to that displayed by Burnside when he expressed an opinion of his own unfitness for the command of the Army of the Potomac. The brave old soldier did not seem to appreciate the strategical situation, and was apparently losing his head.9 With all the advantages of interior lines, he had everywhere opposed the Prussians with inferior numbers; he had allowed the Crown Prince to pass through the defiles of the mountains before he opposed him at all; six of his eight corps had suffered defeat; he had lost more than 30,000 men; and now he was in a purely defensive position, and one which left open the road from Arnau to Gitschin for the junction of the Prussian armies.

It would have been better than this had the Austrians everywhere fallen back without firing a shot, even at the expense of opposing no obstacles to the Prussian concentration; for they could then, at least, have concentrated their own army for a decisive battle without the demoralization attendant upon repeated defeats.

JUNE 30TH

A detachment of cavalry, sent by Frederick Charles towards Arnau, met the advanced-guard of the 1st Corps at that place. Communication was thus opened between the two armies.

It was evident that the advance of Frederick Charles would, by threatening the left and rear of the Austrians, cause them to abandon their position on the Elbe, and thus loosening Von Benedek’s hold on the passages of the river, permit the Crown Prince to cross without opposition.

The following orders were therefore sent by Von Moltke:

“The Second Army will hold its ground on the Upper Elbe; its right wing will be prepared to effect a junction with the left wing of the First Army, by way of Königinhof, as the latter advances. The First Army will press on towards Königgrätz without delay.

“Any forces of the enemy that may be on the right flank of this advance will be attacked by General Von Herwarth, and separated from the enemy’s main force.”

On this day the armies of Frederick Charles marched as follows:

The IIId Corps, to Aulibitz and Chotec;

The IVth Corps, to Konetzchlum and Milicowes;

The IId Corps, to Gitschin and Podhrad;

The Cavalry Corps, to Dworetz and Robaus;

The Army of the Elbe, to the vicinity of Libau;

The Landwehr Guard Division, which had been pushed forward from Saxony, arrived at Jung Buntzlau.10

The Second Army remained in the position of the preceding day.

Von Benedek’s army remained in its position on the plateau of Dubenetz.

JULY 1ST

At 1 o’clock in the morning Von Benedek began his retreat towards Königgrätz.

The IIId Corps moved to Sadowa;

The Xth Corps, to Lipa;

The 3d Reserve Cavalry Division, to Dohalica;

The VIth Corps, to Wsestar;

The 2d Reserve Cavalry Division, to a position between Wsestar and Königgrätz;

The VIIIth Corps, to Nedelist, on left of the village;

The IVth Corps, to Nedelist, on right of the village;

The IId Corps, to Trotina;

The 2d Light Cavalry Division, to the right of the IId Corps;

The 1st Reserve Cavalry Division, behind Trotina;

The 1st Corps took up a position in front of Königgrätz;

The 1st Light Cavalry Division, on the left of the 1st Corps;

The Saxons were stationed at Neu Prim.

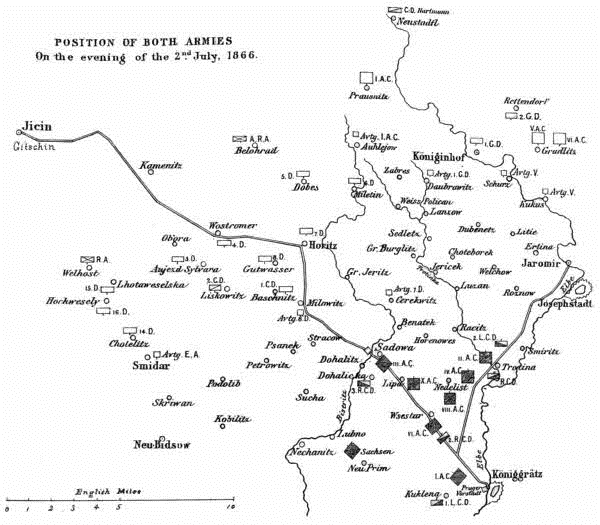

POSITION OF BOTH ARMIES

On the evening of the 2nd. July, 1866.

The Prussian armies, though at liberty to concentrate, remained separated for tactical considerations. The armies were to make their junction, if possible, upon the field of battle, in a combined front and flank attack upon the enemy. In the meantime, as they were only a short day’s march from each other, the danger to be apprehended from separation was reduced to a minimum.

Frederick Charles’ armies moved as follows:

The IIId Corps, to Miletin and Dobes;

The IVth Corps, to Horzitz and Gutwasser;

The IId Corps, to Aujezd and Wostromer;

The 1st Cavalry Division, to Baschnitz;

The 2d Cavalry Division, to Liskowitz;

The Army of the Elbe, to a position between Libau and Hochwesely.

In the Second Army, the Ist Corps was thrown across the Elbe to Prausnitz, and the VIth Corps arrived at Gradlitz.

JULY 2ND

The Army of the Elbe moved forward to Chotetitz, Lhota and Hochweseley, with an advanced-guard at Smidar.

The Guard Landwehr Division advanced to Kopidlno, a few miles west of Hochweseley.

The Austrians remained in the positions of the preceding day, but sent their train to the left bank of the Elbe.

Incredible as it seems, the Prussians were ignorant of the withdrawal of the Austrians from the plateau of Dubenetz, and did not, in fact, even know that Von Benedek had occupied that position. The Austrians were supposed to be behind the Elbe, between Josephstadt and Königgrätz. On the other hand, Von Benedek seems to have been completely in the dark in regard to the movements of the Prussians. The Prussian Staff History acknowledges that “the outposts of both armies faced each other on this day within a distance of four and one-half miles, without either army suspecting the near and concentrated presence of the other one.” Each commander ignorant of the presence, almost within cannon shot, of an enormous hostile army! Such a blunder during our Civil War would, probably, have furnished European military critics with a text for a sermon on the mob-like character of American armies.

Supposing the Austrians to be between Josephstadt and Königgrätz, two plans were open to Von Moltke’s choice. First: To attack the Austrian position in front with the First Army and the Army of the Elbe, and on its right with the Second Army. This would have necessitated forcing the passage of a river in the face of a formidable enemy; but this passage would have been facilitated by the flank attack of the Crown Prince, whose entire army (except the Ist Corps) was across the river. It would have been a repetition of Magenta on a gigantic scale, with the Crown Prince playing the part of McMahon, and Frederick Charles enacting the rôle of the French Emperor. Second: To maneuver the enemy out of his position by moving upon Pardubitz; the occupation of which place would be a serious menace to his communications. The latter movement would necessitate the transfer of the Second Army to the right bank of the Elbe, and then the execution of a flank march in dangerous proximity to the enemy; but its successful execution might have produced decisive results. This movement by the right would have been strikingly similar to Von Moltke’s movement by the left, across the Moselle, four years later. The resulting battle might have been an antedated Gravelotte, and Von Benedek might have found a Metz in Königgrätz or Josephstadt. At the very least, the Austrians would, probably, have been maneuvered out of their position behind the Elbe.

Before determining upon a plan of operations, it was decided to reconnoiter the Elbe and the Aupa. The Army of the Elbe was directed to watch the country towards Prague, and to seize the passages of the river at Pardubitz. The First Army was ordered to take up the line Neu Bidsow-Horzitz and to send a detachment from its left wing to Sadowa, to reconnoiter the line of the Elbe between Königgrätz and Josephstadt. The Ist Corps was to observe the latter fortress, and to cover the flank march of the Second Army, if the movement in question should be decided upon. The remaining corps of the Second Army were, for the present, to remain in their positions, merely reconnoitering towards the Aupa and the Metau.

These orders were destined to be speedily countermanded.

Colonel Von Zychlinsky, who commanded an outpost at the castle of Cerakwitz, reported an Austrian encampment near Lipa, and scouting parties, which were then sent out, returned, after a vigorous pursuit by the Austrian cavalry, and reported the presence of the Austrian army in force, behind the Bistritz, extending from Problus to the village of Benatek. These reports, received after 6 o’clock P. M., entirely changed the aspect of matters.

Under the influence of his war experience, Frederick Charles was rapidly developing the qualities of a great commander; his self-confidence was increasing; and his actions now displayed the vigor and military perspicacity of Mars-la-Tour, rather than the hesitation of Münchengrätz.11 He believed that Von Benedek, with at least four corps, was about to attack him; but he unhesitatingly decided to preserve the advantages of the initiative, by himself attacking the Austrians in front, in the early morning, while the Army of the Elbe should attack their left. The co-operation of the Crown Prince was counted upon to turn the Austrian right, and thus secure victory.

With these objects in view, the following movements were promptly ordered:

The 8th Division to be in position at Milowitz at 2 A. M.;

The 7th Division to take post at Cerakwitz by 2 A. M.;

The 5th and 6th Divisions to start at 1:30 A. M., and take post as reserves south of Horzitz, the 5th west, and the 6th east, of the Königgrätz road;

The 3d Division to Psanek, and the 4th to Bristan; both to be in position by 2 A. M.;

The Cavalry Corps to be saddled by daybreak, and await orders;

The reserve Artillery to Horzitz;

General Herwarth Von Bittenfeld, with all available troops of the Army of the Elbe, to Nechanitz, as soon as possible.

Lieutenant Von Normand was sent to the Crown Prince with a request that he take post with one or two corps in front of Josephstadt, and march with another to Gross Burglitz.

The chief-of-staff of the First Army, General Von Voigts-Rhetz, hastened to report the situation of matters to the King, who had assumed command of the armies on June 30th, and now had his headquarters at Gitschin. The measures taken by Frederick Charles were approved, and Von Moltke at once issued orders for the advance of the entire Second Army, as requested by that commander. These orders were sent at midnight, one copy being sent through Frederick Charles at Kamenitz; the other being carried by Count Finkenstein direct to the Crown Prince at Königinhof. The officer who had been sent by Frederick Charles to the Crown Prince was returning, with an answer that the orders from army headquarters made it impossible to support the First Army with more than the Ist Corps and the Reserve Cavalry. Fortunately, he met Finkenstein a short distance from Königinhof. Comparing notes, the two officers returned together to the Crown Prince, who at once issued orders for the movement of his entire army to the assistance of Frederick Charles.

In order to deliver his dispatches to the Crown Prince, Finkenstein had ridden twenty-two and one-half miles, over a strange road, on a dark, rainy night. Had he lost his way; had his horse suffered injury; had he encountered an Austrian patrol, the history of Germany might have been different. It is almost incredible that the Prussian general should have diverged so widely from the characteristic German prudence as to make success contingent upon the life of an aide-de-camp, or possibly the life of a horse. Even had the other courier, riding via Kamenitz, reached his destination safely, the time that must have elapsed between the Crown Prince’s declension of co-operation and his later promise to co-operate, would have been sufficient to derange, and perhaps destroy, the combinations of Von Moltke.

Let us now examine the Austrian position. Derrécagaix describes it as follows:

“In front of the position, on the west, ran the Bistritz, a little river difficult to cross in ordinary weather, and then very much swollen by the recent rains.

“On the north, between the Bistritz and the Trotina, was a space of about five kilometers, by which the columns of the assailant might advance. Between these two rivers and the Elbe the ground is broken with low hills, covered with villages and woods, which gave the defense advantageous points of support. In the center the hill of Chlum formed the key of the position, and commanded the road from Sadowa to Königgrätz. The heights of Horenowes covered the right on the north. The heights of Problus and Hradek constituted a solid support for the left. At the south the position of Liebau afforded protection on this side to the communications of the army.12

“The position selected had, then, considerable defensive value; but it had the defect of having at its back the Elbe and the defiles formed by the bridges.”

On this subject, however, Hozier says: “The Austrian commander took the precaution to throw bridges over the river. With plenty of bridges, a river in rear of a position became an advantage. After the retreating army had withdrawn across the stream, the bridges were broken, and the river became an obstacle to the pursuit. Special, as well as general, conditions also came into play.... The heavy guns of the fortress scoured the banks of the river, both up and down stream, and, with superior weight of metal and length of range, were able to cover the passage of the Austrians.”

In considering the Austrian retreat, we shall find that neither of these distinguished authorities is entirely right, or wholly wrong, in regard to the defects and advantages of the position described.

The following dispositions were ordered by Von Benedek:

The Saxons to occupy the heights of Popowitz, the left wing slightly refused, and covered by the Saxon Cavalry;

The 1st Light Cavalry Division, to the rear and left, at Problus and Prim;

The Xth Corps on the right of the Saxons;

The IIId Corps to occupy the heights of Lipa and Chlum, on the right of the Xth Corps;

The VIIIth Corps in reserve, in rear of the Saxons.

In case the attack should be confined to the left wing, the other corps were merely to hold themselves in readiness. If, however, the attack should extend to the center and right, the following dispositions were to be made:

The IVth Corps to move up on the right of the IIId to the heights of Chlum and Nedelist;

The IId Corps, on the right of the IVth, constituting the extreme right flank;

The 2d Light Cavalry Division, to the rear of Nedelist;

The VIth Corps to be massed on the heights of Wsestar;

The Ist Corps to be massed at Rosnitz;

The 1st and 3d Cavalry Divisions to take position at Sweti;

The 2d Reserve Cavalry Division, at Briza;

The Reserve Artillery behind the Ist and VIth Corps.

The Ist and VIth Corps, the five cavalry divisions and the Reserve Artillery were to constitute the general reserve.

A slight attempt was made to strengthen the position by throwing up entrenchments. Six batteries were constructed on the right, as well as breastworks for about eight companies of supporting infantry. The infantry breastworks, as well as the batteries, were constructed by engineer soldiers, and were of strong profile, with traverses, and had a command of eight feet. There was not the slightest attempt to have the infantry shelter themselves with hasty entrenchments. Even the earthworks that were constructed were of no use; for a misunderstanding of orders caused the line of battle to be established far in advance of them. On the left but little was done to strengthen the position before the Prussian attack began.

THE BATTLE OF KÖNIGGRÄTZ, JULY 3D

Notwithstanding the heavy rain, the muddy roads, and the late hour at which the orders had been received, the divisions of the First Army were all at their appointed places soon after dawn. The Army of the Elbe pushed forward energetically, and at 5:45 o’clock its commander notified Frederick Charles that he would be at Nechanitz between 7 and 9 o’clock, with thirty-six battalions. The First Army was at once ordered forward.

The 8th Division marched on the left of the high road, as the advanced-guard of the troops moving upon Sadowa.

The 4th and 3d Divisions marched on the right of the road, abreast of the 8th.

The 5th and 6th Divisions followed the 8th on the right and left of the road respectively, while the Reserve Artillery followed on the road itself.

The Cavalry Corps had started from Gutwasser at 5 o’clock, and it now marched behind the right wing to maintain communication with the Army of the Elbe.

The 7th Division was to leave Cerekwitz as soon as the noise of the opening battle was heard, and was to join in the action according to circumstances.

The divisional cavalry of the 5th and 6th Divisions was formed into a brigade, and a brigade of the Cavalry Division was attached to the IId Corps.

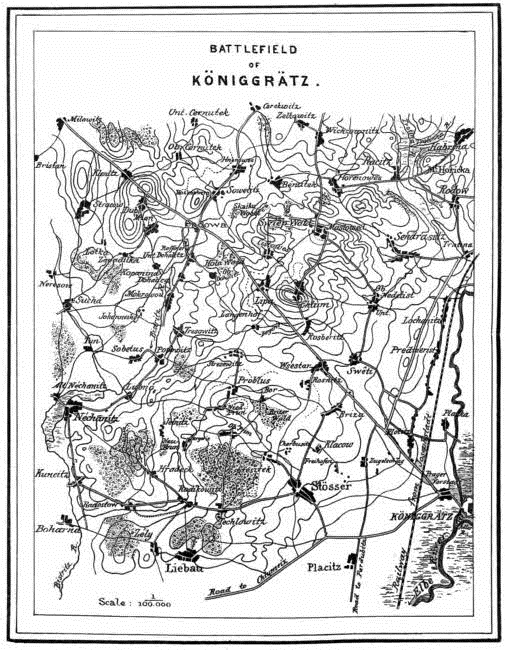

BATTLEFIELD OF KÖNIGGRÄTZ.

About 7:30 the advanced-guard of the Army of the Elbe reached Nechanitz, where it encountered a Saxon outpost, which retired after destroying the bridges.

About the same time the 8th Division advanced in line of battle upon Sadowa. The Austrian artillery opened fire as soon as the Prussians came in sight. The latter took up a position near the Sadowa brickfield, and skirmishing began.

The 4th Division took up a position at Mzan, on the right of the 8th, and its batteries engaged in combat with the Austrian artillery.

The 3d Division formed on the right of the 4th, near Zawadilka.

The 5th and 6th Divisions formed line at Klenitz; one on each side of the road.

The Reserve Cavalry was stationed at Sucha.

At the first sound of the cannon Von Fransecky opened fire upon the village of Benatek, which was soon set on fire by the Prussian shells. The village was then carried by assault by the advanced-guard of the 7th Division.

There was now a heavy cannonade all along the line. The heavy downpour of the last night had given place to a dense fog and a drizzling rain; and the obscurity was heightened by the clouds of smoke which rose from the guns. Frederick Charles rode along the right wing, giving orders to respond to the Austrian batteries by firing slowly, and forbidding the crossing of the Bistritz. His object was merely to contain Von Benedek, while waiting for the weather to clear up, and for the turning armies to gain time.

At 8 o’clock loud cheering announced the arrival of the King of Prussia upon the battle field. As soon as Frederick Charles reported to him the condition of affairs, the King ordered an advance upon the line of the Bistritz. The object of this movement was to gain good points of support for the divisions upon the left bank of the Bistritz, from which they might launch forth, at the proper time, upon the main position of the enemy. The divisions were cautioned not to advance too far beyond the stream, nor up to the opposite heights.

The Austrian position differed slightly from the one ordered on the eve of the battle. The Saxons, instead of holding the heights eastward of Popowitz and Tresowitz, found a more advantageous position on the heights between Problus and Prim, with a brigade holding the hills behind Lubno, Popowitz and Tresowitz. Nechanitz was held merely as an outpost. The remaining dispositions of the center and left were, on the whole, as ordered the night before; on the right they differed materially from the positions designated.

Instead of the line Chlum-Nedelist, the IVth Corps took up its position on the line Cistowes-Maslowed-Horenowes, 2,000 paces in advance of the batteries that had been thrown up.

The IId Corps formed on the right of the IVth, on the heights of Maslowed-Horenowes.

The Ist and VIth Corps and the Cavalry took their appointed positions, and the Reserve Artillery was stationed on the heights of Wsestar and Sweti.

In the language of the Prussian Staff History: “Instead of the semi-circle originally intended, the Austrian line of battle now formed only a very gentle curve, the length of which, from Ober-Prim to Horenowes, was about six and three-fourths miles, on which four and three-fourths corps d’armee were drawn up. The left wing had a reserve of three weak brigades behind it, and on the right wing only one brigade covered the ground between the right flank and the Elbe. On the other hand, a main reserve of two corps of infantry and five cavalry divisions stood ready for action fully two miles behind the center of the whole line of battle.”

The strength of the Austrian army was 206,100 men and 770 guns. At this period of the battle it was opposed by a Prussian army of 123,918 men, with 444 guns. The arrival of the Second Army would, however, increase this force to 220,984 men and 792 guns.

The 7th Division, which had already occupied the village of Benatek, was the first to come into serious conflict with the Austrians. The attack, beginning thus on the left, was successively taken up by the 8th, 4th and 3d Divisions; and the advanced-guard of the Army of the Elbe being engaged at the same time, the roar of battle extended along the entire line.

In front of the 7th Division were the wooded heights of Maslowed, known also as the Swiep Wald. This forest, extending about 2,000 paces from east to west, and about 1,200 from north to south, covered a steep ridge intersected on its northern slope by ravines, but falling off more gradually towards the Bistritz. Against this formidable position Von Fransecky sent four battalions, which encountered two Austrian battalions, and, after a severe struggle, drove them from the wood. Now was the time to break the Austrian line between Maslowed and Cistowes, and, turning upon either point, or both, roll up the flanks of the broken line. The advanced battalions were quickly reinforced by the rest of the division; but all attempts to débouche from the wood were baffled. Heavy reinforcements were drawn from the Austrian IVth and IId Corps, and a furious counter-attack was made upon the Prussians. Calling for assistance, Von Fransecky was reinforced by two battalions of the 8th Division; but he was still struggling against appalling odds. With fourteen battalions and twenty-four guns, he was contending against an Austrian force of forty battalions and 128 guns. Falling back slowly, contesting the ground inch by inch, the Prussian division, after a fierce struggle of three hours, still clung stubbornly to the northern portion of the wood. Still the Austrians had here a reserve of eleven battalions and twenty-four guns, which might have been hurled with decisive effect upon the exhausted Prussians, had not other events interfered.

As soon as the 7th Division had advanced beyond Benatek, the 8th Division advanced against the woods of Skalka and Sadowa. Two bridges were thrown across the Bistritz, west of the Skalka wood, by the side of two permanent bridges, which the Austrians had neglected to destroy. The reserve divisions (5th and 6th) advanced, at the same time, to Sowetitz, and the Reserve Artillery to the Roskosberg. As soon as the 8th Division crossed the Bistritz, it was to establish communication with the 7th Division, and turn towards the Königgrätz highroad. The woods of Skalka and Sadowa were occupied without much difficulty; the Austrian brigade which occupied them falling back in good order to the heights of Lipa, where the other brigades of the IIId Austrian Corps were stationed. On these heights, between Lipa and Langenhof, 160 guns were concentrated in a great battery, which sent such a “hailstorm of shells” upon the advancing Prussians as to check effectually all attempts to débouche from the forests.