полная версия

полная версияLetters from Spain

Before we speak of the co-operation of these powerful men, it is necessary to explain the difficulties which occurred in securing the sanction and assistance of the King himself. Charles III., though no friend to the Jesuits, was still less a friend, either by habit or principle, to innovation. He was not less averse by constitution to all danger. Moreover, he was religious and conscientious in the extreme. The acquiescence and sanction of his Confessor was indispensably necessary to the adoption of any measure affecting the interests of the Church. Neither would the bare consent of the Confessor (in itself no easy matter to obtain) be sufficient. He must be zealous in the cause, and cautious as well as active in the promotion of it. Great secrecy must be observed; for the scheme might be defeated as effectually by indifference or indiscretion as by direct resistance or intrigue. There was little in the character of the Confessor to encourage a man less enterprising or less cunning than Roda.

Fr. Joaquin de Elita, or Father Osma, (so called from the place of his birth) was a friar of little education and less ability, attached by habit to the order to which he belonged, and in other respects exempt from those passions of affection or ambition, as well as from that ardour of temper or force of opinion, which either excite men to great undertakings or render them subservient to those of others. Roda, however, from personal observation, and from an intimate knowledge of those passions which a monastic life generally engenders, discovered the means of engaging even Father Osma in his views. None who have not witnessed it can conceive the effect of institutions, of which vows of perpetual celibacy form a necessary part. Their convent, their order, the place of their nativity, the village or church to which they belong, often engage in the minds of religious men the affections which in the course of nature would have been bestowed on their kindred, their wives, or their children. Padre Elita was born in the city of which the venerable and illustrious Palafox had been bishop. The sanctity of that eminent prelate’s life, the fervour of his devotion, the active benevolence and Christian fortitude of his character, had insured him the reputation of a saint, and might, it was thought, by many Catholics, entitle him to canonization.57 Roda, however, well knew that the Jesuits bore great enmity to his memory on account of his disputes with them in South America; he foresaw that every exertion of that powerful body would be made to resist the introduction of his name into the Rubric. He therefore suggested very adroitly to Father Osma the glory which would redound to his native town if this object could be accomplished. He painted in glowing colours the gratitude he would inspire in Spain, and the admiration he would excite in the Catholic world if through his means a Spaniard of so illustrious a name and of such acknowledged virtue could be actually sainted at Rome. He had the satisfaction of finding that Father Osma espoused the cause with a fervour hardly to be expected from his character. He not only advised but instigated and urged the King to support the pretensions of the bishop of Osma with all his influence and authority. But here an apparent difficulty arose, which Roda turned to advantage, and converted to the instrument of involving the Court of Madrid in an additional dispute with the Roman Pontiff. Charles III. was not unwilling to support the pretensions of his Confessor’s favourite Saint; but he had a job of his own in that branch to drive with the Court of Rome, and he accordingly solicited in his turn the co-operation of Father Osma, to obtain the canonization of Brother Sebastian.

The story of this last-mentioned obscure personage is so curious, and illustrates so forcibly the singular character of Charles, that it will not be foreign to my purpose to relate it.

During Philip the Fifth’s residence in Seville, Hermano Sebastian, a sort of lay-brother58 of the Convent of San Francisco el Grande, was accustomed to visit the principal houses of the place with an image of the Infant Jesus, in quest of alms for his order. The affected sanctity of his life, the demure humility of his manner, and the little sentences of morality with which he was accustomed to address the women and children whom he visited, acquired him the reputation of a saint in a small circle of simple devotees. The good man began to think himself inspired, to compose short works of devotion, and even to venture occasionally on the character of a prophet. Accident or design brought him to the palace: he was introduced to the apartments of the princes, and Charles then a child, took a prodigious fancy to Brother Sebastian of the Niño Jesus, as he was generally called in the neighbourhood, from the image he carried when soliciting alms for his convent. To ingratiate himself with the royal infant, the old man made Charles a present of some prayers written in his own hand, and told him, with an air of sanctified mystery, that he would one day be King of Spain, in reward, no doubt, of his early indications of piety and resignation. The present delighted Charles, and, young as he was, the words and sense of the prophecy sunk deep in his superstitious and retentive mind. Though he was seldom known to mention the circumstance for years, yet he never parted with the manuscript. It was his companion by day and by night, at home and in the field. When he was up, it was constantly in his pocket; and it was placed under his pillow during his hours of rest. But when, by his accession to the crown of Spain, its author’s prediction was fulfilled, the work acquired new charms in his eyes, his confidence in Brother Sebastian’s sanctity was confirmed, and his memory was cherished with additional fondness by the grateful and credulous monarch. At the same time, therefore, that the pretensions of the Bishop of Osma to canonization were urged at Rome, the Spanish minister was instructed to speak a good word for the humble friar Sebastian. The lively and sarcastic Azara was entrusted with this negotiation; and, as I know that he was at some pains to preserve the documents of this curious transaction, it is not impossible that he may have left memoirs of his life, in which the whole correspondence will, no doubt, be detailed with minuteness and exquisite humour.

The Court of Rome is ever fertile in expedients, especially when the object is to start difficulties and suggest obstacles to any design. The investigation of Palafox’s pretensions was studiously protracted; and it was easy to perceive that the influence of the Jesuits in the Sacred College was exerted to throw new impediments in the way of their adversary’s canonization. Though the Court of Rome could never seriously have thought of giving Brother Sebastian a place in the Rubric, they amused Charles III. by very long discussions on his merits, and went through, with scrupulous minuteness, all the previous ceremonies for ascertaining the conduct of a saint.

It is a maxim, that the original of every writing of a person claiming to be made a saint, must be examined at Rome by the Sacred College, and that no copy, however attested, can be admitted as sufficient testimony, if the original document is in existence. The book, therefore, to which the Spanish Monarch was so attached, was required at Rome. Here was an abundant source of negotiation and delay. Charles could not bring himself to part with his treasure, and the forms of canonization precluded the College from proceeding without it. At length, the King, from his honest and disinterested zeal for the friar, was prevailed upon. But Azara was instructed to have the College summoned, and the Cardinals ready, on the day and even the hour at which it was calculated that the most expeditious courier could convey the precious book from Madrid to Rome. Relays were provided on the road, and Charles III. himself deposited the precious manuscript in the hands of his most trusty messenger, with long and anxious injunctions to preserve it most religiously, and not to lose a moment in sallying forth from Rome on his return, when the interesting contents of the volume should have been perused.

The interim was to Charles III. a “phantasma, or a hideous dream.” He never slept, and scarcely took any nourishment during the few days he was separated from the beloved paper. His domestic economy, and the regulation of his hours, which neither public business nor private affliction in any other instance disturbed, was altered; and the chase, which was not interrupted even by the illness and death of his children, was suspended till Brother Sebastian’s original MS. could again accompany him to the field. He stood at the window of his palace counting the drops of rain on the glasses, and sighing deeply. Business, pleasure, conversation, and meals, were suspended, till the long-expected treasure returned, and restored the monarch to his usual avocations.

When, however, his Confessor discovered that the Court of Rome was trifling with their solicitations, that to Palafox there was an insurmountable repugnance, and when the King began to suspect that the sacrifice he had been compelled to make was all to no purpose, and that the pains of separation had been inflicted upon him without the slightest disposition to grant him the object for which alone he had been inclined to endure it, both he and his Confessor grew angry. The opposition to their wishes was, perhaps, truly, and certainly industriously traced to the Jesuits.

In the mean while a riot occurred at Madrid. In 1766, the people rose against the regulation of police which attempted to suppress the cloaks and large hats, as affording too great opportunities for the concealment of assassins. These and other obnoxious measures were attributed to the Marquis of Squilace, who, in his quality of favourite as well as foreigner, was an unpopular minister of finance. Charles III. was compelled to abandon him; and the Count of Aranda, disgraced under Ferdinand VI. and lately appointed to the captain-generalship of Valencia, was named President of the council of Castile, for the purpose of pacifying by his popularity, and suppressing by his vigour, the remaining discontents of the people. He entered into all Roda’s views. As an Aragonese, he was an enemy of the Colegios Mayores, for they admitted few subjects of that Crown to their highest distinctions: and as a freethinker, and man of letters, he was anxious to suppress the Jesuits.

Reports, founded or unfounded, were circulated in the country, and countenanced by these powerful men, that the Jesuits had instigated the riots of Madrid. It was confidently asserted, that many had been seen in the mob, though disguised; and Father Isidro Lopez, an Asturian, who was considered as one of the leading characters in the company, was expressly named as having been active in the streets. Ensenada, the great protector of the Jesuits in the former reign, had been named by the populace as the proper successor of Squilace, and there were certainly either grounds for suspecting, or pretexts for attributing the discontent of the metropolis to the machinations of the Jesuits and their protector the ex-minister Ensenada. Enquiries were instituted. Many witnesses were examined; but great secrecy was preserved. It is, however, to be presumed, that, under colour of investigating the causes of the late riot, Aranda and Roda contrived to collect every information which could inflame the mind of the King against those institutions which they were determined to subvert. They had revived the controversy respecting the conduct of the venerable Palafox, and drawn the attention both of Charles III. and the public to the celebrated letter of that prelate, in which he describes the machinations of the Jesuits in South America, and which their party had but a few years since sentenced to be publicly burnt in the great square of Madrid.

But, even with the assistance of Father Osma, the acquiescence of the King, and the concert of many foreign enemies of the Company, Roda and Aranda were in want of the additional aid which talents, assiduity, learning, and character could supply, to carry into execution a project vast in its conception, and extremely complicated, as well as delicate in its details. They found it in the famous Campomanes. Perhaps the grateful recollection of services, and the natural good-nature of Jovellanos, led him to praise too highly his early protector and precursor, in the studies which he himself brought to greater perfection. But Campomanes was an enlightened man, and a laborious as well as honest minister. He was at that time Fiscal of the Council and Chancellor of Castile, and considered by the profession of the law, as well as by the great commercial and political bodies throughout Spain, as an infallible oracle on all matters regarding the internal administration of the kingdom. The Coleccion de Providencias tomadas por el gobierno sobre el estrañamiento y ocupacion de temporalidades de los Regulares de la Compañia (Collection of measures taken by the Government for the alienation and seizure of the temporalities of the Regulars of the company of Jesuits) is said to be a monument of his diligence, sagacity, and vigour.

A royal decree was issued on 27th February, 1767, and dated from el Pardo, by which a Junta, composed of several members of the Royal Council, was instituted, in consequence of the riot of Madrid of the preceding year. To this Junta several bishops, selected from those who were most attached to the doctrines of Saint Thomas Aquinas, and, consequently, least favourable to the Jesuits, (for they espouse the rival tenets,) were added for the purpose of giving weight and authority to their decree. In this Junta the day and form of the measure were resolved upon, and instructions drawn out for the Magistrates who were to execute it both in Spain and in America, together with directions for the nature of the preparations, the carriages to be provided at the various places inland, and the vessels to be ready in the ports. The precautions were well laid. The secret was wonderfully kept; and on the night of the first of April, at midnight precisely, every College of the Jesuits throughout Spain was surrounded by troops, and every member of each collected in their respective chapters, priests or lay-brothers, young or old, acquainted with the decree, and forcibly conveyed out of the kingdom. Their sufferings are well known; and the fortitude with which they bore them must extort praise even from those who are most convinced of the mischiefs which their long influence in the courts of Europe produced. The expulsion and persecution of the French priests during the Revolution was more bloody, but scarcely less inhuman, than the hardships inflicted by the regular and legitimate monarchies which had originally encouraged them, on the Jesuits. On the other hand, the suppression of that society was favourable to the cause of liberty, morals, and even learning;—for though their system of education has been much extolled, it must be acknowledged that in Spain, at least, the period at which the education of youth was chiefly entrusted to Jesuits, is that in which Castilian literature declined, and general ignorance prevailed. If the state of education in a country is to be judged of by its fruits, the Jesuits in Spain certainly retarded its progress. In relation to the rest of Europe, the Spaniards were farther advanced in science and learning during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, than during the seventeenth and eighteenth; and since the suppression of the Company, in 1767, and not till then, a taste for literature and a spirit of improvement revived among them.

NOTES

NOTE A On the Devotion of the Spaniards to the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary.—p. 22The history of the transactions relative to the disputes on the immaculate conception of the Virgin Mary, even when confined to those which took place at Seville, could not be compressed within the limits of one of the preceding letters. Such readers, besides, as take little interest in subjects of this nature, would probably have objected to a detailed account of absurdities, which seem at first sight scarcely to deserve any notice. Yet there are others to whom nothing is without interest which depicts any peculiar state of the human mind, and exhibits some of the innumerable modifications of society. Out of deference, therefore, to the first, we have detached the following narrative from the text of Doblado’s Letters, casting the information we have collected from the Spanish writers into a note, the length of which will, we hope, be excused by those of the latter description.

The dispute on the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin began between the Dominicans and Franciscans as early as the thirteenth century. The contending parties stood at first upon equal ground; but “the merits of faith and devotion” were so decidedly on the side of the Franciscans, that they soon had the Christian mob to support them, and it became dangerous for any Divine to assert that the Mother of God (such is the established language of the Church of Rome) had been, like the rest of mankind, involved in original sin. The oracle of the Capitol allowed, however, the disputants to fight out their battles, without shewing the least partiality, till public opinion had taken a decided turn.

In 1613, a Dominican, in a sermon preached at the cathedral of Seville, threw out some doubts on the Immaculate Conception. This was conceived to be an insult not only to the Virgin Mary, but to the community at large; and the populace was kept with difficulty from taking summary vengeance on the offender and his convent. Zuñiga, the annalist of Seville, who published his work in 1677, deems it a matter of Christian forbearance not to consign the names of the preacher and his convent to the execration of posterity. But if the civil and ecclesiastical authorities exerted themselves for the protection of the offenders, they were also the first to promote a series of expiatory rites, which might avert the anger of their Patroness, and make ample reparation to her insulted honour. Processions innumerable paraded the streets, proclaiming the original purity of the Virgin Mother; and Miguél del Cid, a Sevillian poet of that day, was urged by the Archbishop to compose the Spanish hymn, “Todo el Mundo en general,” which, though far below mediocrity, is still nightly sung at Seville by the associations called Rosarios, which have been described in Doblado’s Letters.59

The next step was to procure a decision of the Pope in favour of the Immaculate Conception. To promote this important object two commissioners were dispatched to Rome, both of them dignified clergymen, who had devoted their lives and fortunes to the cause of the Virgin Mary.

After four years of indescribable anxiety the long wished-for decree, which doomed to silence the opponents of Mary’s original innocence, was known to be on the point of passing the seal of the Fisherman,60 and the Sevillians held themselves in readiness to express their unbounded joy the very moment of its arrival in their town. This great event took place on the 22d of October 1617, at ten o’clock P.M. “The news, says Zuñiga, produced a universal stir in the town. Men left their houses to congratulate one another in the streets. The fraternity of the Nazarenes joining in a procession of more than six hundred persons, with lighted candles in their hands, sallied forth from their church, singing the hymn in honour of Original Purity. Numerous bonfires were lighted, the streets were illuminated from the windows and terraces, and ingenious fireworks were let off in different parts of the town. At midnight the bells of the cathedral broke out into a general chime, which was answered by every parish church and convent; and many persons in masks and fancy dresses having gathered before the archbishop’s palace, his grace appeared at the balcony, moved to tears by the devout joy of his flock. At the first peal of the bells all the churches were thrown open, and the hymns and praises offered up in them lent to the stillness of night the most lively sounds of the day.”

A day was subsequently fixed when all the authorities were to take a solemn oath in the Cathedral, to believe and assert the Immaculate Conception. An endless series of processions followed to thank Heaven for the late triumph against the unbelievers. In fact, the people of Seville could not move about, for some time, without forming a religious procession. “Any boy,” says a contemporary historian, “who, going upon an errand, chose to strike up the hymn Todo el Mundo, were sure to draw after him a train, which from one grew up into a multitude; for there was not a gentleman, clergyman, or friar, who did not join and follow the chorus which he thus happened to meet in the streets.”

Besides these religious ceremonies, shows of a more worldly character were exhibited. Among these was the Moorish equestrian game, called, in Arabic, El Jeerid, and in Spanish, Cañas, from the reeds which, instead of javelins, the cavaliers dart at each other, as they go through a great variety of graceful and complicated evolutions on horseback.61 Fiestas Reales, or bull-fights, where gentlemen enter the arena, were also exhibited on this occasion. To diversify, however, the spectacle, and indulge the popular taste, which requires a species of comic interlude, called Mogiganga, a dwarf, whose diminutive limbs required to have the stirrups fixed on the flap of the saddle, mounted on a milk-white horse, and attended by four negroes of gigantic stature, dressed in a splendid oriental costume, fought with one of the bulls, and drove a full span of his lance into the animal’s body—a circumstance which was deemed too important to be omitted by the historiographers of Seville.

The most curious and characteristic of the shows was, however, an allegorical tournament, exhibited at the expense of the company of silk-weavers, who, from the monopoly with the Spanish Colonies, had attained great wealth and consequence at that period. It is thus described, from the records of the times, by a modern Spanish writer.

“Near the Puerta del Pardon (one of the gates of the cathedral), a platform was erected, terminating under the altar dedicated to the Virgin, which stands over the gate.62 Three splendid seats were placed at the foot of the altar, and two avenues railed in on both sides of the platform to admit the Judges, the challenger, the supporters or seconds, the marshal, and the adventurers. Near one of the corners of the stage was pitched the challenger’s tent of black and brown silk, and in it a seat covered with black velvet. In front stood the figure of an apple-tree bearing fruit, and hanging from its boughs a target, on which the challenge was exposed to view.

“At five in the afternoon, the Marshal, attended by his Adjutant, presented himself in the lists. He was followed by four children, in the dress used to represent angels, with lighted torches in their hands. Another child, personating Michael the Archangel, was the leader of a second group of six angels, who were the bearers of the prizes—a Lamb and a Male Infant. The Judges, Justice and Mercy, appeared last of all, and took their appointed seats.

“The sound of drums, fifes, and clarions, announced soon after, the approach of another group, composed of two savages of gigantic dimensions, with large clubs on their shoulders, eight torch-bearers in black, and two infernal Furies, and, in the centre, the challenger’s shield-bearer, followed by the challenger’s supporter or second, dressed in black and gold, with a plume of black and yellow feathers. This band having walked round the stage, the second brought the challenger out of the tent, who, dressed uniformly with his supporter, appeared wielding a lance twenty-five hands in length.63

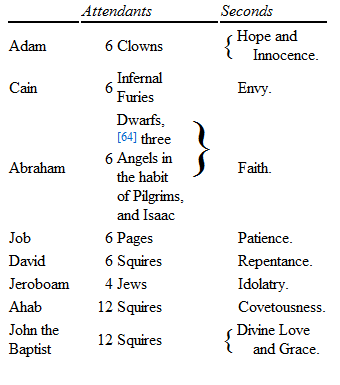

The following is a list of the Adventurers, their attendants, or torch-bearers, and supporters or seconds:—

64Dwarfs were formerly very common among the servants of the Spanish nobility. But it is not easy to guess for what reason they were allotted to Abraham, on this occasion.

“The dresses (continues the historian) were all splendid, and suited to the characters.