полная версия

полная версияAmerican Pomology. Apples

Mr. Du Breuil also refers to Leport's liquid mastic in terms of commendation, but speaks of it as a secret composition.

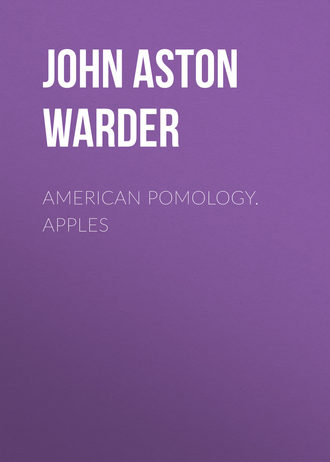

Downing recommends melting together:

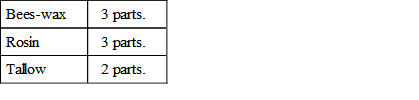

He says, the common wax of the French is

To be boiled together, and laid on with a brush, and for using cold or on strips of muslin, equal parts of tallow, bees-wax, and rosin, some preferring a little more tallow.

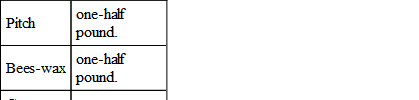

J.J. Thomas, whose practical knowledge is proverbial, recommends for its cheapness

Melted together, to be applied warm with a brush, or to be put on paper or muslin, or worked with wet hands into a mass and drawn out into ribbons.

The season for grafting is quite a prolonged one, if we include the period during which it may be done in the house, and the ability we have of retarding the scions by cold, using ice. It should be done while the grafts are dormant, which is at any time from the fall of the leaf until the swelling of the buds. As the grafts would be likely to suffer from prolonged exposure, out-door grafting is done just before vegetation commences in the spring, but may be prolonged until the stocks are in full leaf, by keeping back the scions, in which case, however, there is more danger to the stock unless a portion of its foliage is allowed to remain to keep up the circulation; under these circumstances, too, side-grafting is sometimes used with the same view.

The stone fruits are worked first; cherries, plums, and peaches, then pears and apples. With regard to grafting grapes, there is a diversity of opinion. Some operators prefer very early in the season, as in February, and others wait until the leaves have appeared upon the vine to be grafted.

Scions or Grafts are to be selected from healthy plants of the variety we wish to propagate. They should be the growth of the previous year, of average size, well developed, and with good buds, those having flower buds are rejected. If the shoots be too strong, they are often furnished with poor buds, and are more pithy, and therefore they are more difficult to work and are less likely to grow. Grafts, cut from young bearing orchards, are the best, and being cut from fruiting trees, this enables us to be certain as to correctness of the varieties to be propagated; but they are generally and most rapidly collected from young nursery trees, and as an orchardist or nurseryman should be able to judge of all the varieties he cultivates by the appearance of their growth, foliage, bark, dots, etc., there is little danger in taking the scions from such untested trees.

Time for cutting Scions.—The scions may be cut at any time after the cessation of growth in the autumn, even before the leaves have fallen, until the buds burst in the spring, always avoiding severely cold or frosty weather, because of the injury to the tree that results from cutting at such a time, though the frost may not have injured the scion. The best nurserymen prefer to cut them in the autumn, before they can have been injured by cold. They should be carefully packed in fine earth, sand, or sawdust, and placed in the cellar or cave. The leaves stripped from them, make a very good packing material; moss is often used, where it can be obtained, but the best material is saw-dust. This latter is clean, whereas the sand and soil will dull the knife. If the scions should have become dry and shriveled, they may still be revived by placing them in soil that is moderately moist, not wet—they should not, by any means, be placed in water, but should be so situated that they may slowly imbibe moisture. When they have been plumped, they should be examined by cutting into their tissues; if these be brown, they are useless, but if alive, the fresh cut will look clear and white, and the knife will pass as freely through them as when cutting a fresh twig.

The after-treatment of the grafts consists in removing the sprouts that appear upon the stock below the scion, often in great numbers. These are called robbers, as they take the sap which should go into the scion. It is sometimes well to leave a portion of these as an outlet for excess. When the graft is tardy in its vegetation, and in late grafting, it is always safest to leave some of these shoots to direct the circulation to the part, and thus insure a supply to the newly introduced scion; all should eventually be removed, so as to leave the graft supreme.

It may sometimes be necessary to tie up the young shoot which pushes with vigor, and may fall and break with its own weight before the supporting woody fibre has been deposited; but a much better policy is to pinch in the tip when but a few inches long, and thus encourage the swelling and breaking of the lateral buds, and produce a more sturdy result. This is particularly the case in stock-grafts and in renewing an orchard by top-grafting.

PROPAGATION.—SECTION III.—BUDDING

ADVANTAGES OF—LONG PERIOD FOR—CLAIMS OF GREATER HARDINESS EXAMINED—LATE GROWERS APT TO BURST THE BARK—BUD TENDER SORTS. STOCKS NOT ALWAYS HARDY—PHILOSOPHY OF BUDDING, LIKE GRAFTING, DEPENDS UPON CELL-GROWTH—THE CAMBIUM, OR "PULP"—THE BUD, ITS INDIVIDUALITY—THOMSON QUOTED—UNION DEPENDS UPON THE BUD—SEASON FOR BUDDING—CONDITIONS REQUISITE—SPRING BUDDING—CONDITION OF THE BUDS—BUD STICKS—SELECTION OF—THEIR TREATMENT—RESTORATION WHEN DRY—THE WEATHER—RAINS TO BE AVOIDED—USUAL PERIOD OF GROWTH BY EXTENSION—SUCCESSION OF VARIETIES—CHERRY, PLUM, PEAR, APPLE, QUINCE, PEACH—HOW TO DO IT—DIFFERENT METHODS—AGE OF STOCKS—PREPARATION OF—THE KNIFE—CUTTING THE BUDS—REMOVAL OF THE WOOD—THE AMERICAN METHOD—DIVISION OF LABOR TYING—RING BUDDING—PREPARATION OF SCIONS FOR EARLY BUDDING—IMPROVEMENTS IN TYING—BAST, PREPARATION OF—SUBSTITUTES—NOVEL TIE—WHEN TO LOOSEN THE BANDAGE—HOW DONE—INSPECTION OF BUDS—SIGN OF THEIR HAVING UNITED—KNIGHT'S TWO BANDAGES—WHY LEAVE THE UPPER ONE LONGER. HEADING BACK THE STOCKS—RESUME.

Budding, or inoculating, is the insertion of eyes or buds. This is a favorite method of propagation, which is practiced in the multiplication of a great variety of fruits. The advantages of budding consist in the rapidity and facility with which it is performed, and the certainty of success which attends it. Budding may be done during a long period of the growing season, upon the different kinds of trees we have to propagate. Using but a single eye, it is also economical of the scions, which is a matter of some importance, when we desire to multiply a new and scarce variety.

It has been claimed on behalf of the process of budding, that trees, which have been worked in this method, are more hardy and better able to resist the severity of winter than others of the same varieties, which have been grafted in the root or collar, and also that budded trees come sooner into bearing. Their general hardiness will probably not be at all affected by their manner of propagation; except perhaps, where there may happen to be a marked difference in the habit of the stock, such for instance as maturity early in the season, which would have a tendency to check the late growth of the scion placed upon it—the supplies of sap being diminished, instead of continuing to flow into the graft, as it would do from the roots of the cutting or root-graft of a variety which was inclined to make a late autumnal growth. Practically, however, this does not have much weight, nor can we know, in a lot of seedling stocks, which will be the late feeders, and which will go into an early summer rest.

Certain varieties of our cultivated fruits are found to have a remarkable tendency to make an extended and very thrifty growth, which, continuing late into the autumn, would appear to expose the young trees to a very severe trial upon the access of the first cold weather, and we often find them very seriously injured under such circumstances; the bark is frequently split and ruptured for several inches near the ground. The twigs, still covered with abundant foliage, are so affected by the frost, that their whole outer surface is shriveled, and the inner bark and wood are browned; the latter often becomes permanently blackened, and remains as dead matter in the centre of the tree, for death does not necessarily ensue. Now intelligent nurserymen have endeavored to avoid losses from these causes, by budding such varieties upon strong well-established stocks, though they are aware that these are not more hardy than some of the cultivated varieties: a given number of seedling stocks has been found to suffer as much from the severity of winter, as do a similar amount of the grafted varieties taken at random.14 That the serious difficulty of bark-bursting occurs near the surface of the ground, does seem to be an argument of some weight in favor of budding or stock-grafting at a higher point. The earlier fruiting of budded trees than those which have been root-grafted, does not appear to be a well established fact, and therefore need not detain us; except to observe that the stocks, upon which the buds were inserted, might have been older by some years than the slip of root upon which the graft was set, so that the fruiting of the former tree should count two or three or more years further back than from the period of the budding. There are so many causes which might have contributed toward this result of earlier bearing, that we should not be too hasty in drawing conclusions in this matter.

The philosophy of budding is very similar to that of grafting. The latter process is performed when the plant-life is almost dormant, and the co-apted parts are ready to take the initiative steps of vegetation, and to effect their union by means of new adventitious cells, before the free flow of sap in the growing season. Budding, on the contrary, is done in the hight of that season and toward its close, when the plants are full of well matured and highly organized sap, when the cell circulation is most active, and the union between the parts is much more immediate than in the graft; were it not so, indeed, the little shield, with its actively evaporating surface of young bark, must certainly perish from exposure to a hot dry atmosphere. The cambium, or gelatinous matter, which is discovered between the bark and the wood when they are separated, is a mass of organizable cells. Mr. Paxton, using the gardener's expression, calls it the "pulp." Budding is most successfully performed when this matter is abundant, for then the vitality of the tree is in greatest degree of exaltation.

The individuality of the bud was sufficiently argued in the first section of this chapter, it need not now be again introduced, except as appropriately to remind us of the fact where the propagation depends upon this circumstance—the future tree must spring from the single bud which is inserted. Mr. A.T. Thomson, in his Lectures on the Elements of Botany, page 396, says:—"The individuality of buds must have been suspected as early as the discovery of the art of budding, and it is fully proved by the dissection of plants. * * Budding is founded on the fact, that the bud, which is a branch in embryo, is a distinct individual. It is essential that both the bud and the tree into which it is inserted should not only be analogous in their character, as in grafting with the scion, but both must be in a state of growth at the time the operation is performed. The union, however, depends much more upon the bud than upon the stock—the bud may be considered a centre of vitality—vegetative action commences in the bud, and extends to the stock, connecting them together."—"The vital energy, however, which commences the process of organization in the bud, is not necessarily confined to the germ, nor distinct from that which maintains the growth of the entire plant; but it is so connected with organization, that when this has proceeded a certain length, the bud may be removed from the parent and attached to another, where it will become a branch the same as if it had not been removed."

The season for budding has already been indicated in general terms, it is usually done in mid-summer and the early part of autumn, reference being had to the condition of the plants to be worked; these should be in a thrifty growing state, the woody fibre should be pretty well advanced, but growth by extension must still be active, or the needful conditions will not be found. The "pulp" must be present between the bark and the wood of the stock, so that the former can be easily separated from the latter; in the language of the art, the bark must "run;" this state of things will soon cease in most stocks, after the formation of terminal buds on the shoots. The success of spring budding, however, would appear to indicate that the cambium layer is formed earlier in the season than is usually supposed; for whenever the young leaves begin to be developed on the stock, "the bark will run," and the buds may be inserted with a good prospect of success. In this case we are obliged to use dormant buds that were formed the previous year, and we have to exercise care in the preservation of the scions, to keep them back by the application of cold, until the time of their insertion.

The condition of the bud is also important to the success of the operation. The tree from which we cut the scions should be in a growing state, though this is not so essential as in the case of the stock, as has been seen in spring budding—still, a degree of activity is desirable. The young shoot should have perfected its growth to such an extent as to have deposited its woody fibre, it should not be too succulent; but the essential condition is, that it should have its buds well developed. These, as every one knows, are formed in the axils of the leaves, and, to insure success, they should be plump and well grown. In those fruits which blossom on wood shoots of the previous year's growth, as the peach and apricot, the blossom buds should be avoided; they are easily recognized by their greater size and plumpness. In cutting scions, or bud-sticks, the most vigorous shoots should be avoided, they are too soft and pithy; the close jointed firm shoots, of medium size, are much to be preferred, as they have well developed buds, which appear to have more vitality. Such scions are found at the ends of the lateral branches. These need immediate attention, or they will be lost. The evaporation of their juices through the leaves would soon cause them to wither and wilt, and become useless. These appendages are therefore immediately removed by cutting the petioles from a quarter to half an inch from the scion; a portion of the stem is thus left as a convenient handle when inserting the shield, and this also serves afterward as an index to the condition of the bud. So soon as trimmed of their leaves, the scions are tied up, and enveloped loosely in a damp cloth, or in moss, or fresh grass, to exclude them from the air. If they should become wilted, they must not be put into water, as this injures them; it is better to sprinkle the cloth and tie them up tightly, or they may be restored by burying them in moderately moist earth.

The early gardeners were very particular as to the kind of weather upon which to do their budding. They recommended a cloudy or a showery day, or the evening, in order to avoid the effects of the hot sunshine. This might do in a small garden, where the operator could select his opportunity to bud a few dozen stocks; but even there, wet weather should be avoided, rather than courted. But in the large commercial nurseries, where tens of thousands of buds are to be inserted, there can be no choice of weather; indeed, many nurserymen prefer bright sunshine and the hottest weather, as they find no inconvenience arising to the trees from this source. Some even aver that their success is better under such circumstances, and argue that the "pulp is richer."

Most trees in their mature state make all their growth by extension or elongation very early in the season, by one push, as it were; with the first unfolding of the leaves, comes also the elongation of the twig that bears them. In most adult trees in a state of nature, there is no further growth in this way, but the internal changes of the sap continue to be effected among the cells during the whole period of their remaining in leaf, during which there is a continual flow of crude sap absorbed by the roots, and taken up into the organism of the tree to aid in the perfection of all the various parts, and in the preparation of the proper juice and the several products peculiar to the tree, as well as its wood and fruits. When all this is transpiring within its economy, the tree is said to be in its full flow of sap; at this stage the young tree is in the best condition for budding, but it continues also, if well cultivated, to grow by extension for a greater or shorter portion of the season, and this is essential to the success of the operation as already stated. After the perfecting of the crop of fruit, the main work of the tree seems to have been done for the year, and we often observe, particularly with the summer fruits, that the trees appear to go to rest after this period, and begin to cast their foliage. Now, to a certain extent, this is true of the young trees. The varieties that ripen their fruit early, make their growth in the nursery in the earlier portion of the summer, they stop growing, and their terminal bud is formed and is conspicuous at the top of the shoots. Very soon the supply of sap appears to be diminished, there is no longer so much activity in the circulation, the bark cleaves to the wood, it will no longer run, and the season of budding for those stocks has reached its terminus; hence the nurseryman must be upon the look-out for the condition of his trees. Fortunately, those species which have the shortest season, are also the first to be ready, the first to mature their buds, and they must be budded first. We may commence with the cherry, though the Mahaleb stock, when it is used, continues in condition longer than other varieties, and may be worked late. The plum and pear stocks also complete their growth at an early period in the season; the apple continues longer in good condition, and may be worked quite late. Grapes, if worked in this way, should be attended to about mid-season, while they are still growing; but quinces and peaches may be kept in a growing state much later than most other stocks, and can be budded last of all.

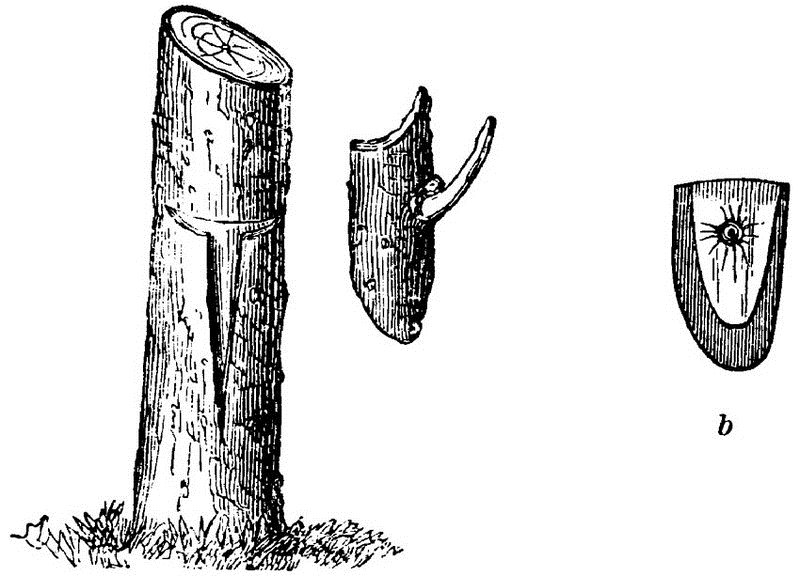

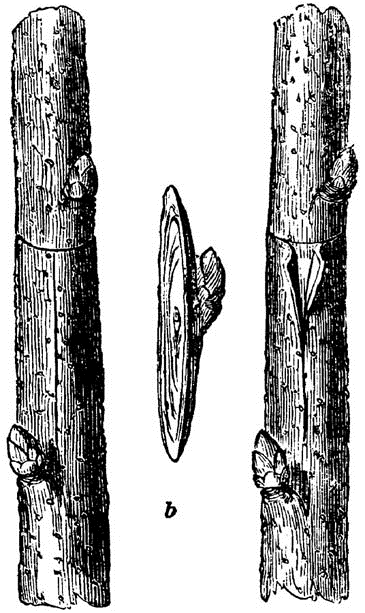

How to do it.—The stocks being in a suitable condition as above described, they should be trimmed of their lateral shoots for a few inches from the ground. This may be done immediately in advance of the budder, or it may have been done a few days before the budding. The stock may be one year old, or two years; after this period they do not work so well. The usual method is to make a T incision through the bark of the stock, as low down as possible, but in a smooth piece of the stem; some prefer to insert the shield just below the natural site of a bud. The knife should be thin and sharp, and if the stock be in good condition, it will pass through the bark with very little resistance; but if the stock be too dry, the experienced budder will detect it by the different feeling communicated through his knife, by the increased resistance to be overcome in making the cut. The custom has been to raise the bark by inserting the haft of the budding knife gently, so as to start the corners of the incision, preparatory to inserting the bud; but our best budders depend upon the shield separating the bark as it is introduced. The bud is cut from the scion by the same knife, which is entered half an inch above the bud, and drawn downward about one-third the diameter of the scion, and brought out an equal distance below the bud; this makes the shield, or bud. The authorities direct that the wood should be removed from the shield before it is inserted; this is a nice operation, requiring some dexterity to avoid injuring the base of the bud, which constitutes its connection with the medulla or pith within the stick. The base of the bud is represented by b, figure 17. Various appliances have been invented to aid in this separation, some use a piece of quill, others a kind of gouge; but if the bark run freely on the scion, there will be little difficulty in separating the wood from the shield with the fingers alone. All this may be avoided by adopting what is called the American method of budding, which consists in leaving the wood in the shield, (fig. 18, b) that should be cut thinner, and is then inserted beneath the bark without any difficulty, and may be made to fit closely enough for all practical purposes. Like everything else American, this is a time-saving and labor-saving plan, and therefore readily adopted by the practical nurseryman, who will insert two thousand in a day.

Fig. 17.—BUDDING, WITH THE WOOD REMOVED. b, THE INSIDE OF THE SHIELD SHOWING THE BASE OF THE BUD.

Fig. 18.—AMERICAN BUDDING. b, THE BUD WITH THE WOOD REMAINING.

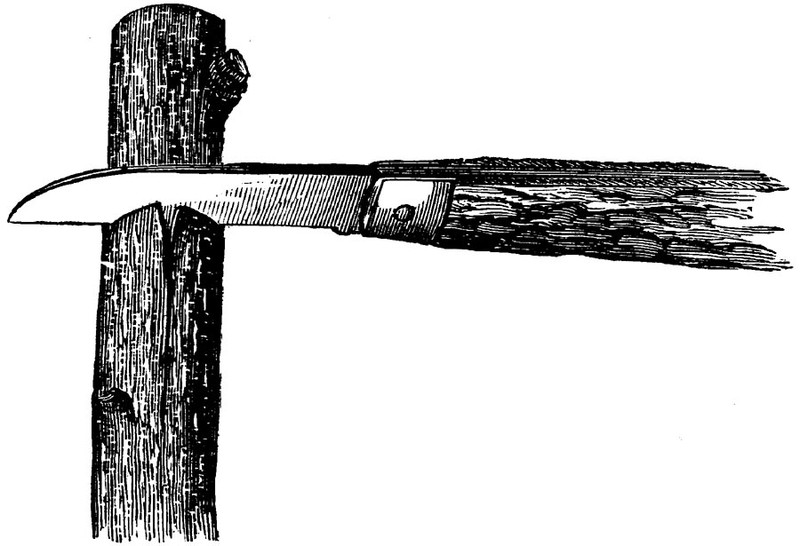

A division of labor is had generally, so far as the tying is concerned; for this is done by a boy who follows immediately after the budder, and some of these require two smart boys. S.S. Jackson has carried this principle of division of labor still further, and, as appears, with advantage; one hand cuts the shields for another who inserts them. He never uses the haft of his knife to raise the bark, but, after having made the longitudinal cut through the bark, he places the knife in position to make the transverse incision, and as he cuts the bark, the edge of the blade being inclined downward, the shield is placed on the stock close above the knife, which is then still further inclined toward the stock, resting upon the shield as a fulcrum; thus started, the bark will readily yield to the shield, which is then pressed down home into its place.

Fig. 19.—MR. JACKSON'S METHOD OF MAKING THE INCISION.

J.W. Tenbrook, of Indiana, has invented a little instrument with which he makes the longitudinal and transverse incisions, and raises the bark, all at one operation, and inserts the bud with the other hand. On these plans, two persons may work together, one cutting, the other inserting the buds; these may change work occasionally for rest. In all cases it is best to have other hands to tie-in the buds, two or three boys will generally find full occupation behind a smart budder. It will be apparent that the above processes can only be performed when the stock is in the most perfect condition of growth, so that the bark can be pressed away before the bud; a good workman will not desire to bud under any other circumstances.

In budding, it is found that the upper end of the shield is the last to adhere to the stock; it needs to be closely applied and pressed by the bandage, and if too long, so as to project above the transverse incision, it should be cut off.

Fig. 20.—STICK OF BUDS.

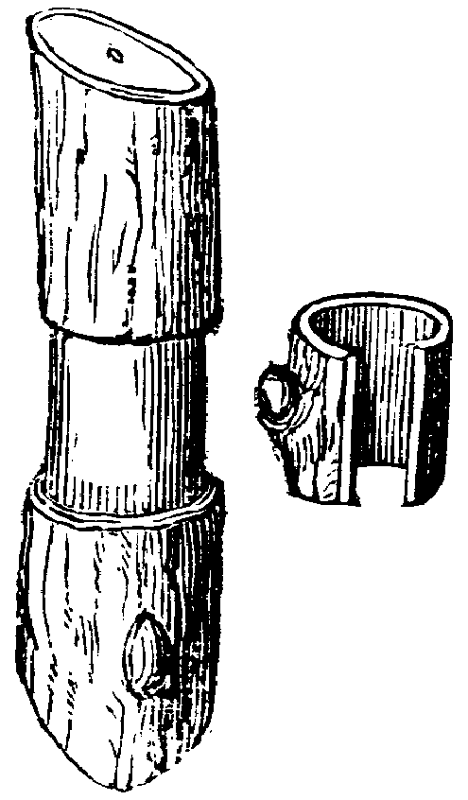

Fig. 21.—RING BUDDING.

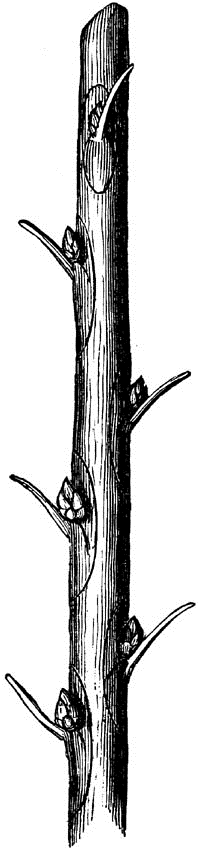

Another expedient for facilitating the operation of budding is made use of by some of the nurserymen who grow peach trees extensively. It consists in, preparing the stick of buds, as shown in the engraving, figure 20. A cut is made, with a sharp knife, through the bark, around each bud, as in the figure. The budder then removes the buds as they are wanted, with a slight sidewise pull, and has the shield in the right condition to insert, without the trouble of removing the wood. When working in this manner, the stick of buds must not be allowed to dry, and the work must be done at a time when the bark parts with the greatest ease.

Among the modifications of the process of budding, that, called ring-budding, fig. 21, may be mentioned, rather as a curiosity however, though preferred by some, especially for the grape, which is said to be very easily budded, though we seldom see the operation practiced.