полная версия

полная версияAmerican Pomology. Apples

IMPORTANCE OF SEIZING THE STRONG MARKS—EXTERNAL; WEIGHT, SHAPE, SIZE, SURFACE—BASIN AND EYE—CAVITY AND STEM—INTERNAL; FLESH, CORE, AXIS, SEEDS, FLAVOR—THESE CONSIDERED SEPARATELY AND ILLUSTRATED—EXPLANATION OF TERMS USED—SHAPE REFERRED TO RELATIONS OF THE DIAMETERS; AXIAL AND TRANSVERSE—LEADING FORMS DESCRIBED AND ILLUSTRATED—SIZE, A COMPARATIVE TERM—SKIN CHARACTERS, COLOR; ITS USE IN CLASSIFYING—PERMANENCE OF STRIPES—LINES—DOTS AND SPECKS—FUNGOUS SPOTS—FORMS OF BASIN AND EYE, OF CAVITY AND STEM, ARE VALUABLE; TERMS USED—THE INTERIOR, AXIS, CORE, SEEDS, FLESH—FLAVOR UNCERTAIN—SWEET AND SOUR GOOD CHARACTERS—QUALITY, TERMS EXPRESSIVE OF.

In the description of a fruit, it is very desirable for the writer to catch the strong characters, so that he, who reads, may the more readily identify the specimen he holds in his hand. Among these several characters there is considerable difference as to their permanence and value; some are evanescent, some variable, while others are found to be more reliable and constant. Let us consider some of these in the systematic order by which they will be taken in the descriptions that are to follow.

In describing a fruit, the firmness, weight, and external characters, first claim our attention, then the internal; these are taken up in the following order: externally, its shape, size, surface, color, and dots are examined. In the apple and pear the basin is next observed and its characters noted, with any peculiarities connected with the eye, by which term the triangular space is designated that is embraced by the calyx, as shown in an axial section of the fruit; at the same time the length and breadth and shape of the calyx segments are noted. The other end of the fruit is then explored as to the form and markings of the cavity, and the length, size, and peculiarities of the stem. Having thus disposed of the externals, we are now to investigate the nature of the internal structure; to do this, a section is made vertically through the middle of the fruit from the eye to the stem, which exposes the flesh, the axis with its core and the seeds, and which enables us to investigate some very important characters, such as the length of the axis, its form and that of its carpels, and the manner of their union, whether they form an open core or otherwise.

The number, color, and shape of the seeds are noted. The color of the flesh, its texture and juiciness are examined; the latter qualities are always tested by the teeth, and then the palate gives us an account of the degree of richness, acidity, or sweetness and flavor. The investigator is now prepared to render judgment; having the testimony of his organs of touch, sight, taste and smell, he can pronounce his decision as to quality, and is prepared to specify the particular uses to which the fruit is especially adapted; whether for the table as a dessert, for the kitchen, as in baking and stewing, or for drying, or whether it be valuable for cider-making. A good judge will now be able to decide whether the fruit be especially adapted for the market or for the amateur. The season of ripening should be noted in this place, with any remark as to qualities not already provided for.

Form is one of our most permanent characters; though subject to modifications, the general shape of the specimens is always characteristic of the variety. Even a novice will soon learn the peculiar outline of a variety of fruit.

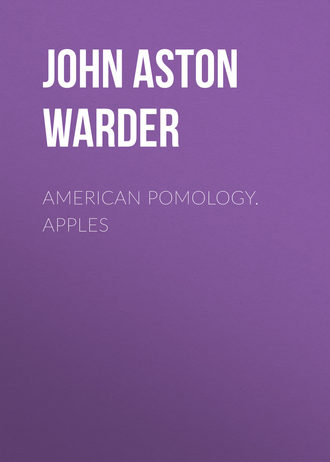

Before commencing the study of these varieties of form, it will be well to explain some of the leading terms introduced. By referring to the illustrations, it will be observed that the outlines are inscribed in circles to which they are compared; these are drawn with dotted lines, and they are bisected with cross lines representing the two diameters referred to in the classification by form: the vertical or axial diameter, AA, passing through the axis of the fruit, and the transverse diameter, BB, at right angles to the vertical.

The Form may be round or globular when it is nearly spherical; the two diameters, the axial and transverse, being nearly equal; fig. 30.

Globose is another term of about the same meaning.

Conic, or conical, indicates a decided contraction toward the blossom end, fig. 31; Ob-conic implies that the cone is very short or flattened.

Oblong means that the axial diameter is the longer, or that it appears so, for an oblong apple may have equal diameters; fig. 32.

Oblong-conic, that the outline also tapers rapidly toward the eye; fig. 33.

Oblong-ovate, that it is fullest in the middle; and like

Ovate, which means egg-shaped, that it tapers to both ends; fig. 34.

Oblate, or flattened, when the axial diameter is decidedly the shorter; fig. 35.

Obtuse is applied to any of these figures that is not very decided.

Cylindrical and truncate are dependent upon one another, thus a globular, or still more remarkably, an oblong fruit, which is abruptly truncated or flattened at the ends, appears cylindrical in its form.

Depressed is an unusually flattened oblate form.

Turbinate or top-shaped, and pyriform or pear-shaped, are especially applicable to pears, and seldom to apples.

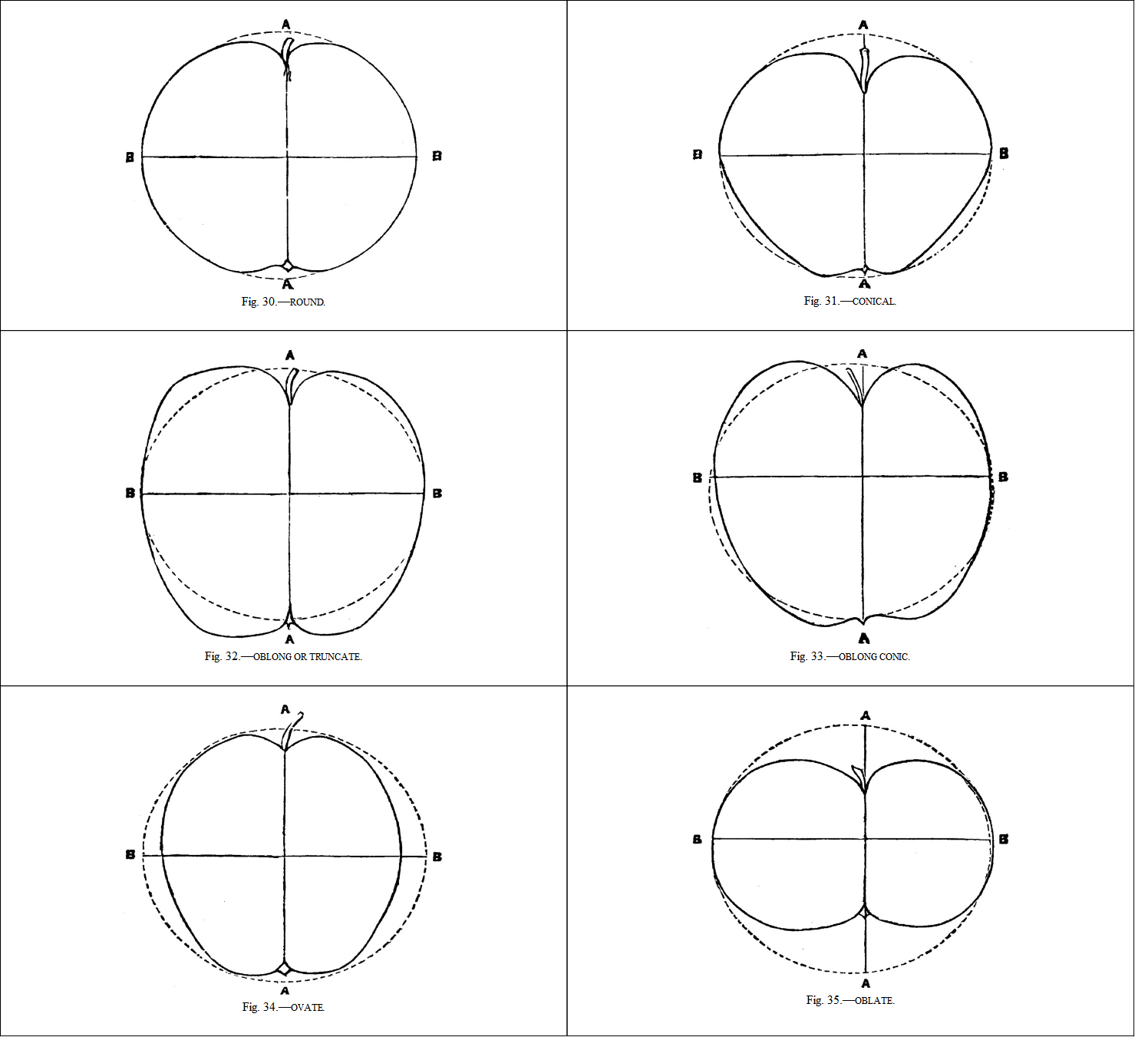

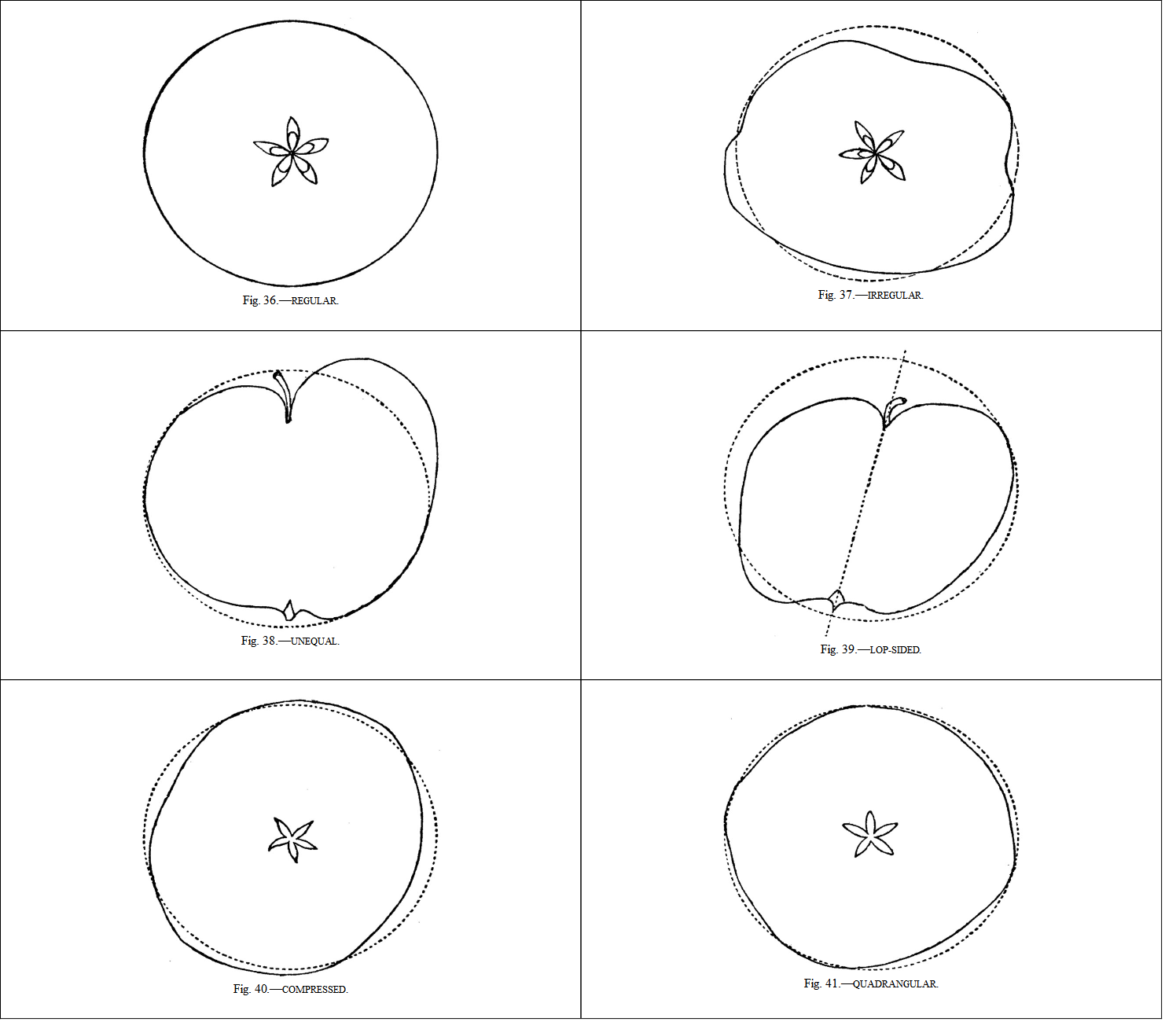

When these forms are described evenly about a vertical axis, as shown by a section of the fruit made transversely, or across the axis, the specimen may be called regular or uniform, fig. 36; if otherwise, it is irregular, fig. 37, unequal, fig. 38, oblique or lop-sided, fig. 39, in which last cases the axis is inclined to one side. If the development at the surface is irregular, as in the Duchesse d'Angouleme and Bartlett pears, the fruit is termed uneven.

When a transverse section of the fruit, made at right angles to the axis, gives the figure of a circle, the fruit is regular; if otherwise, it may be compressed or flattened at the sides, fig. 40; angular, quadrangular, fig. 41; sulcate or furrowed, fig. 42, when marked by sulcations; or ribbed, fig. 43, when the intervening ridges are abrupt. Heart-shaped is a form that applies more especially to the cherry, than any other kind of fruit.

Size is a character of but second rate importance, since it is dependent upon the varying conditions of soil, climate, overbearing, etc. It has its value, however, when it is considered as comparative or relative. The expressions employed in this work to indicate size, are: very large, large, medium, small, very small, making five grades.

The characters of the Skin and surface are generally very reliable, though the smoothness of the skin as well as the coloring depend upon both soil and climate. We find, however, that a striped apple which has been shaded, though pale, will always betray itself by a splash or stripe, be it ever so small or rare, nor will any exposure so deepen and exaggerate its stripes as to make it a self-colored fruit; and no circumstances will introduce a true stripe upon a self-colored variety. Hence we may consider this kind of marking a reliable character, and apply it as an element of our classification. We sometimes find lines on self-colored fruits that are as distinctive as the stripes, but entirely distinct from them.

The skin itself may be either thick or thin, smooth, rough, or polished, and it is sometimes uneven; it may be covered with a bloom, it may be russeted in whole or in part, and this may be thickly or thinly spread over the surface, or only net-veined. A sort of russeting occurs about the stem only in some varieties, and is never seen in others, making a pretty good character, but in the same variety it is often much increased or diminished.

This character, russet on the skin, has been very puzzling to young pomologists in the study of pears, owing to its liability to exaggeration in some varieties, under the influence of certain climatic conditions that have even produced it in varieties in which it had not been previously suspected. Some pears are characterized by this russeting of the skin, either generally spread over the surface or confined to a limited area at either end of the fruit, particularly about the insertion of the stem; others have never shown any disposition to put on this character, but, under certain circumstances some varieties, which should have been smooth and fair, become thickly spread with this russeting, that seems even to thicken the skin and which deteriorates the qualities of the fruit. In some cases this appearance is local, occupying one end of the fruit, or making a band around the middle and contracting it like a cincture, as though its presence prevented the proper growth and development of the sarcocarp or fleshy mass of the fruit.

The colors themselves being as various almost as the hues of the rainbow, will be designated by their appropriate or customary names; the manner of their laying on will require the use of certain definite terms, which should be understood to comprehend the classification, which, in part, depends upon this circumstance. Thus a fruit is called self-colored when it is not striped, though it may be blushed or bronzed, and the coloring may be so broken, without stripes, as to be mixed or curdled, blotched, marbled, mottled, clouded, spotted, stained, shaded or dappled; but some of these characters are often found associated with striping also, or they are observed in those kinds of fruit that are always devoid of stripes. Striped fruits are often so deeply colored that the separate stripes do not appear so distinctly, as when there are fewer of them on a lighter ground and they can scarcely be perceived. When the stripes are long and distinct, they are called streaks; when short and broken abruptly at their ends, the surface is said to be splashed. Certain pears are striped by a paleness or faintness of color, these are called panache, and are considered sports of their namesake varieties which they resemble in other respects. A few peaches are distinctly striped; some plums and cherries obscurely so.

Another class of surface or skin characters consists in the Dots and Specks, which appear to be very valuable distinctive markings, on account of their uniformity in different varieties. These may be large or small, numerous or scattered, darker or lighter colored, prominent or indented. In shape they are round or elongated, and this last is a valuable character because quite rare. Sometimes the dots are characterized by having a green base or areola around them, which is very noticeable, and in some varieties these marks, which are perhaps the stomata of the skin, are surrounded by distinct rings of a gray color, that resemble ocellations or eyes. No reliance can be placed upon the delicate coloring that is often to be seen upon the surface of certain light colored fruits, making rose, red, or purplish tints about these dots, as they are accidental only and not distinctive markings.

No one should confound these pores, that are designated as the dots, with the superficial and extraneous marks that appear to be the accidental growth of some fungus or lichen, and which are very commonly found upon the surface of many fruits, often giving them a quite pretty appearance that would be seized upon by the fruit painter as a special beauty, unless when so abundant as to produce an unpleasant smutchiness or cloudiness, such as is often found in the product of apple orchards that are situated in low bottom lands, and which peculiarity is attributed to the influence of fogs.

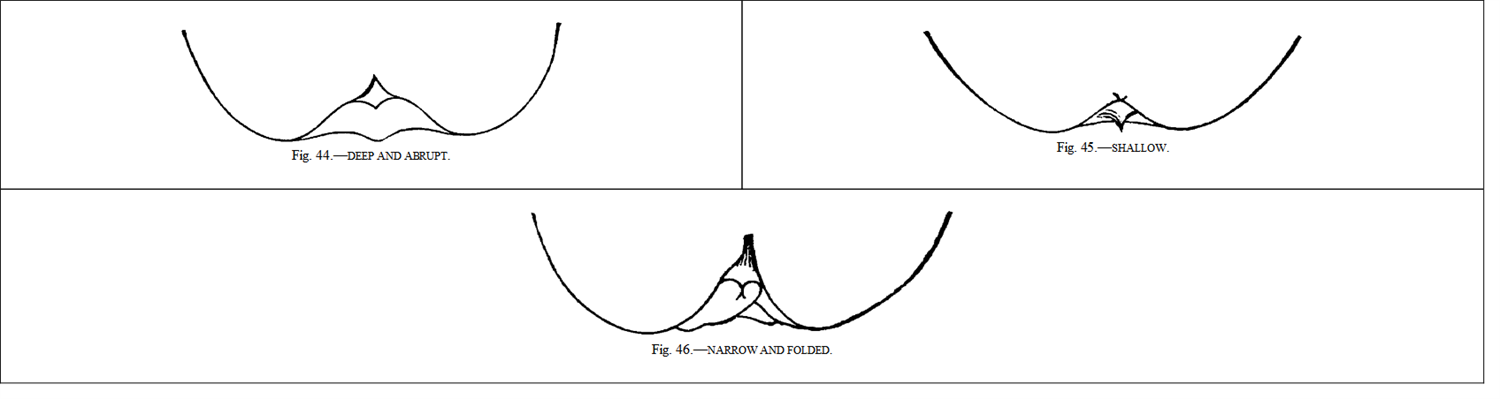

The Basin or Apex of a fruit consists of that portion most distant from the stem. In the apple and pear it is commonly called the blossom end, and is often more or less depressed; hence the term basin. In other fruits it is called the point or apex. Both are characterized by peculiarities of form that serve as distinctive marks in the description of fruits, and these are characters of considerable value on account of their permanence. In respect to its form, the basin, according to its depth, is called deep, fig. 44; shallow, fig. 45; very shallow, or medium. It is abrupt, fig. 44, when the edges are steep; it is narrow and pointed, fig. 46, or wide; it is regular, or wavy, wrinkled, plaited, folded, ribbed or angular, fig. 46—when these peculiarities exist.

Some fruits are russeted at this part of their surface only, but this marking is a variable character and is found in greater or less degree in different localities; thus the Rhode Island Greening, to which it belongs, is sometimes almost entirely divested of the russeting, and in other localities the surface is thickly spread with it half way to the stem; the Westfield Seek-no-further, which is slightly marked with this character in the North, often becomes a russet apple in more southern latitudes.

The basin of some fruits is very apt to crack into irregular fissures, and this appears to be peculiar to certain varieties, though it is not esteemed a very reliable mark; the term cracked is used to express this. In some fruits, however, we find a very peculiar cracking that forms a permanent character, upon which great dependence may be placed: all the rim of the basin in these is marked with a slightly cracked appearance that does not rupture the skin, and which resembles the incipient breaking of the surface of a piece of dry leather; it has, therefore, received the name of leather-crack. This is characteristic of a few sorts, and hence a valuable mark.

Within the basin is the Eye, which furnishes characters of great value. This I consider to mean the meeting of the segments of the calyx, and more particularly in the apple, the triangular space enclosed by these parts, in which the remains of the stamens and pistils are found. Hence the Eye can only be displayed by making a vertical section of the fruit. There are but a limited number of expressions used in its description; thus the eye is said to be large, small, long or short, and it may be open or closed. The segments of the calyx may be converging or reflexed, persistent or obsolete, according to their condition in the ripe fruit, and these several characters are quite reliable; but the simple fact that the eye is open or closed, may depend upon the accidental breaking away of the segments of the calyx, and is of little value as a sign.

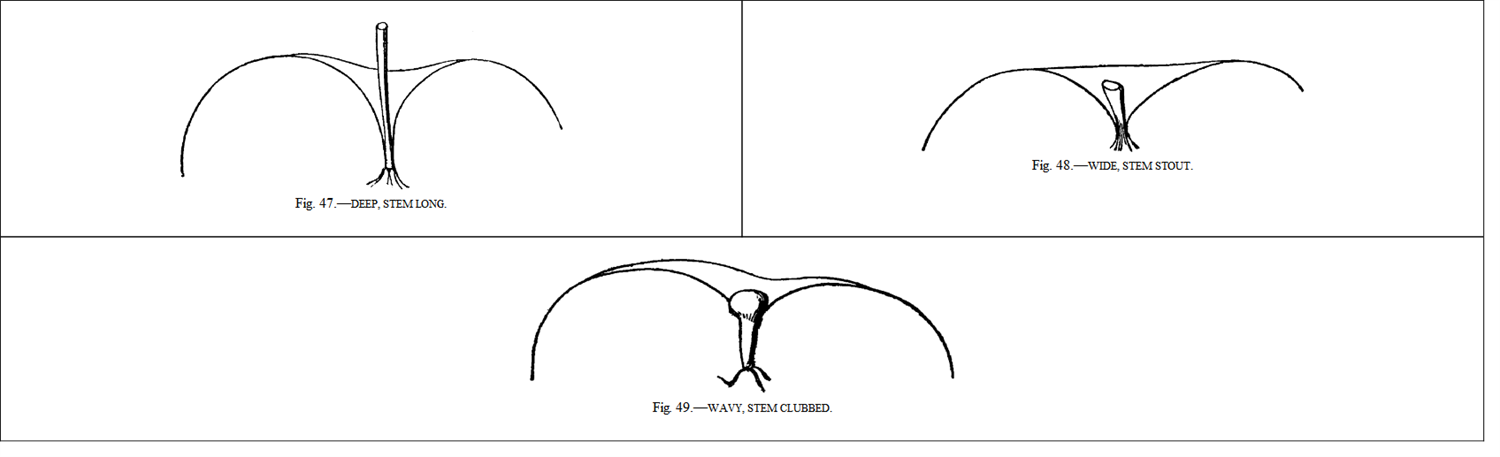

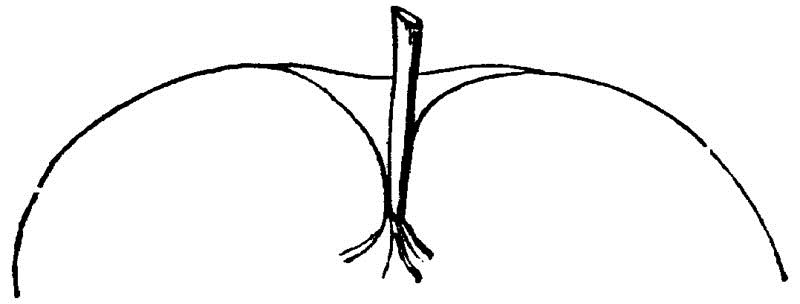

The next character to be considered is the attachment of the stem, which, in some fruits, is so depressed as to constitute what is called the Cavity. In the apple this portion has many variations that are quite characteristic of certain varieties of fruit. In form the cavity may be either deep, fig. 47, or shallow; regular or irregular; wide, fig. 48; or narrow, and acute, wavy, fig. 49; and uneven, folded, and even lipped, fig. 50; as when a portion of the flesh protrudes against the stem, as in Pryor's Red, Roman Stem, and other apples, and in some pears. This portion is sometimes defaced by cracks that separate the skin; it is occasionally green, and this is a good and distinguishing character of a limited number of fruits, both apples and pears. The cavity is also brown or "russeted" in some fruits, and, though this character is quite variable in its depth, amount and extent, we may consider the brown or russeting about the stem quite reliable in both pears and apples.

Fig. 50.—CAVITY LIPPED.

The stem has its place of insertion in the region we have just been considering. It is the peduncle of botanists, and in some species it separates from the fruit by a joint—in others it remains attached and separates from the twig, when it is considered a part of the fruit itself, as in the apple and pear. The shape, average length, thickness, and other characters, and especially its mode of attachment to the carpos45 in the pear, give us some important characters, but these are always somewhat uncertain and variable; hence they are rather relative than positive traits. In apples, stems may be long, fig. 47, short, fig. 48, or medium, according to their projection beyond or concealment within the cavity, being called medium when they simply reach the contour of the outline. They are slender, fig. 47; medium or thick, fleshy, knobby or clubbed, fig. 49, according to the amount of their substance and its arrangement. They are curved or straight, and direct and axial, or inclined, according to their direction and relation to the axis of the fruit; and in pears, they often have a peculiarity of the insertion dependent upon their being more or less fleshy; in both plums and pears, this fullness is often arranged in rings surrounding the base of the stem.

Some pomologists have taken great pains to measure the length of the stems, which they report in inches and lines. As above stated, this is an uncertain quantity, and therefore of little value, except when taken in relation to other measurements by way of comparison; hence I have preferred to use the above-mentioned terms only in their relation to the axial diameter in describing the apples, unless where their extension is unusual. The variable length of this organ in some varieties is remarkable, and we often find the smallest fruits having the longest stems.

When we come to examine the interior portions of a fruit, if it be an apple or pear, we make a vertical section through the axis from basin to cavity. This exposes the internal structure and enables us to judge of the color and other characters of the fleshy pericarp, the length of the axis, the size of the core and carpels, and the number and appearance of the seeds. These characters are possessed of value, and are quite reliable; in many fruits the seeds furnish distinctive indications, and this is particularly the case with the stone fruits, many of which are readily identified by the form and markings of the stones or pits, the endocarps of botany.

In the apple particularly, we first have our attention drawn to the Axis, which is sometimes very short, so that in some decidedly oblate specimens, with deep basin and cavity, there is scarcely room between them for the core, which is shortened to correspond with the oblate character of the fruit. This is illustrated by many of the outlines given in Class I. It is well also to observe and note whether the axis be inclined. The form of the core is not very reliable, but it has characters that are permanent and peculiar to certain varieties. Thus it is always open in some, and always closed in other sorts of the apple. In the pear it is gritty in some varieties, and surrounded with fine grained flesh in others. The core is large, medium, or small, and these distinctions are permanent. Its outline, embracing the group of carpels, may be regular or irregular, long or short, cordate, wide or compressed; it may reach the eye or otherwise, and it frequently clasps that portion.

The Seeds are numerous or otherwise; they are long or short, acuminate or rounded, flat, angular, imperfect, or plump, large or small; they may be pale, even yellow, or brown, dark, and nearly black; and these shades are distinctive, often enabling the pomologist to decide upon the variety when other characters are less marked. The peculiarities of the stones of peaches, plums and cherries, and of the seeds of the grape, had better be described in immediate connection with those species of fruit.

In the Flesh of fruits we find characters that most pomologists, even the amateurs, are generally pleased to have under practical consideration. They are also very reliable, for if the fruits be in good condition, they are always the same in any given variety. In its consistency, this tissue is either firm and compact, or spongy; it is fine grained, granular, gritty, fibrous, or breaking, on the one hand, or tender, buttery and melting, on the other; the flesh is either dry or juicy, and tinted with various shades of color. In some we find a satisfying richness, while others are thin and poor. Some have a fine aroma, while others have an unpleasant flavor or are scentless.

So intimately associated are our organs of taste and smell, that it is difficult to separate and distinguish the impressions we receive through these senses. For our present purpose it will be best to consider all under this head, whether really belonging to one or the other sensation; and the lexicographers themselves admit the commonalty of taste and smell in the word flavor. These qualities of a fruit depend upon so many accidents of season, culture, and especially of the condition of ripeness, that they are of comparatively little value in descriptions, except in their broadest expressions of acidity and its opposite, which indeed are sufficiently pronounced to be used in the classification of fruits.

With regard to their Flavor, fruits may be said to be vinous, sub-acid, acid, and very acid, or sugary, sweet, very sweet, and honey sweet; they may be flat and insipid, or highly flavored, mild, or astringent; and as to fragrance, in which they may remind us of many other agreeable odors, they may be said to be perfumed and aromatic, or otherwise.

In deciding upon the quality of the fruit that has thus been subjected to this series of tests, and to this thorough examination, we shall find that the decision will depend upon the individual tastes, the likes and dislikes of those who are called upon to render judgment, and that, at best, the result must be arbitrary. The terms expressive of this division are inferior, good, very good, and best.

CHAPTER XVI

CLASSIFICATION

NECESSITY FOR—BASIS OF—CHARACTERS—SHAPE—ITS REGULARITY. FLAVOR—COLOR—THEIR SEVERAL VALUES—THOMAS' CLASSIFICATION—GERMAN WRITERS—DIEL'S SEVEN CLASSES—MODIFICATIONS BY DOCHNAHL—ROBERT HOGG'S MODIFICATION BASED UPON SEASON—DIEL'S CONSPECTUS OF CLASSIFICATION—DOCHNAHL'S—THE AUTHOR'S CLASSIFICATION EXPLAINED—EXPLANATION OF TERMS—TOPICS COMBINED—CONSPECTUS OF CLASSIFICATION USED IN THIS WORK.

The need of some classification grows more and more pressing, as our fruit lists have become more extended, and they now reach many hundreds. A good and reliable systematic classification has become absolutely necessary, and has received a great deal of consideration.

Upon what principle shall this classification be founded? The common alphabetical arrangement of most text books may be very convenient for a mere dictionary of fruits, but is utterly useless to the novice who does not know the name of his specimen. The arrangement by season and size has its difficulties in the uncertainty and variation of these characters in the different soils and climates of our extended country, and a sub-division and grouping of fruits by their quality of excellence is not only unreliable, but is altogether arbitrary, and subject to the greatest diversity of opinion arising from the various tastes of different individuals. We must look to some marked and reliable characters that are always present, easily recognized, and permanent or fixed. Among these shape or figure stands pre-eminent, notwithstanding the acknowledged fact that some varieties are almost protean. The shape of the general outline appears to be the best character for the broad divisions of a classification. A sub-division may again be made, which is to be based upon the regularity or irregularity of the shape.