полная версия

полная версияAmerican Pomology. Apples

Thinning is not often practiced upon the strawberry crop, which appears able upon suitable soils to produce a great abundance of fine fruit, but it may be done by the curious, and enormous show specimens, such as are often exhibited at fairs, are produced by special care and high manuring, aided greatly by judicious thinning; not only by cutting back a portion of the crowns, so as to throw the whole force of the plant into one or two trusses, but still further, by removing with the scissors a portion of the blossoms or fruit, so that the few which are left may become enormously distended with the nutriment that had been stored up in the plant for a much greater number. Some may consider this one of the tricks of the trade, and so it is when merely done for the sake of deceiving the public, who are asked to purchase the variety by the sample of fruit, without detailing the arts by which the results were accomplished: but there can be no objection raised against such practices when pursued by the amateur for the sake of producing unusually large fruits of any variety.

The English pursue a similar method with their show gooseberries; by means of thinning and high feeding, with great attention to watering, these fruits are made to assume gigantic proportions that are little dreamed of by cultivators of the smaller varieties, which are chiefly grown in this country.

The grape is very prone to over-production, and the crop, as well as the vine itself, is often much injured by a want of attention to this particular. So avaricious is man, that few persons will exert the needed firmness and perseverance to remove the excess which the beautiful vine annually affords. The result of this neglect is apparent at the vintage, especially when from any fault of the season, or from the invasion of insects or of mildew, the foliage may have been damaged, as it frequently is, to a considerable extent. Then we find large quantities of the grapes so deficient in color and flavor as to be worthless; in some varieties whole bunches will hang flaccid, withered, and insipid—while perhaps a few, more favorably situated, will have their proper flavor. The grape vine is well called beautiful, and it is capable of sustaining most wonderful amounts of fruit; but on young vines, especially, it is very bad policy to allow of this over-production.

The tendency to fruitage may be met in different ways, a few of which will now be pointed out, and all planters are urged to observe and to practice some of these plans for reducing the exuberance of this kind of fruit. In the first place we practice winter pruning, regardless of its established and well-known effect of producing an increase of wood-growth, for this is what we desire to obtain in the vine, on account of its habit of yielding its fruit on wood of the previous year's growth; by this means we are able to pursue the renewal system, which is so generally preferred, and thus we may keep our vines perpetually clothed with new wood, or canes as they are technically called. By this winter pruning we can reduce the amount of wood that is of a bearing character, to any point which may be deemed desirable, according to the strength and age of the vine, and thus the crop is thinned by a wholesale process of lopping off the superabundance of buds, that would have produced an excess of fruit. Another method of thinning is, to rub out a portion of the shoots, this may be every alternate branch in close jointed varieties of the vine: this is to be done soon after the buds have burst, and while the branches are yet quite small, so that the vital forces may be directed to those that remain. Wherever double shoots appear, the weaker should always be removed.

Still another method of reducing the superabundance, remains to be noticed; this consists in thinning the grapes themselves, the separate berries, which, in some varieties, are often so crowded upon the bunch, as to prove a serious injury to one another. In hardy out-door culture this is seldom practiced, being less necessary than in the large varieties of foreign grapes that are grown under glass. These are systematically thinned with the scissors, so that none shall crowd together; and this process, repeated from time to time, is found to produce much finer and larger berries and heavier bunches than when all are left.

A very rude method has sometimes been pursued in thinning the superabundance of fruit upon apple trees. It appears so very Gothic that its description may only excite a smile, when it is stated that it consists in threshing the tree with a long slender pole, by which a portion of the fruit is cast to the ground. Rude and primitive as this method may appear, it is surely better than no thinning at all, and is attended with this good result, for which it deserves some commendation; the threshing removes portions of the excessive twiggy spray that always abounds upon such trees as those under consideration, and thus, in a degree, it prevents the recurrence of so heavy a crop the following year. Whenever an old orchard has reached this condition of over-fruitfulness, however, the best method of thinning is to give a severe winter pruning; removing portions of the spray and encouraging the free growth of young wood in various parts of the top, to replace the older portions that were removed.

CHAPTER XII

RIPENING AND PRESERVING FRUITS

CHANGES DURING THE PROCESS OF RIPENING—ANNUALS RIPEN THEIR FRUIT AND DIE—PERENNIALS HAVE AN ACCUMULATION OF STRENGTH—YOUNG PLANTS OFTEN FAIL TO PERFECT THEIR FRUIT—THE NECESSITY FOR THINNING—ALTERNATE CROPS OF FRUIT FAVOR THE ACCUMULATION—CHANGES IN CONDITION OF PERICARP—GREEN FRUITS APPROPRIATE CARBON—GIVE OFF CARBONIC ACID AS THEY RIPEN—COMPOSITION OF RIPE SUCCULENT FRUITS—FORMATION OF SUGAR—INFLUENCE OF LIGHT, OF EXCESSIVE MOISTURE—TESTS OF RIPENESS—CHANGES AFTER SEPARATION DEPEND UPON OXIDATION—TIME REQUIRED FOR RIPENING—FROM BLOSSOMING BLOSSOMS RENDERED ABORTIVE BY TOO HIGH TEMPERATURE—TREES ARE ABORTIVE FROM EXCESSIVE WOOD-GROWTH—EXPERIENCE REQUIRED TO JUDGE OF RIPENESS—PRACTICAL TEST—GATHERING—SOME MATURE ON THE TREE; OTHERS, PLUCKED PREMATURELY, WILL RIPEN—EFFECTS ON KEEPING QUALITIES—SELECT FINE WEATHER—HANDLING—PACKING—THE GATHERING BAG—WHY RED APPLES ARE PREFERRED.

PRESERVATION—LOW TEMPERATURE AND DRYNESS, BUT AVOIDING FROST AND DESICCATION—COVERING IN PILES—THE RAIL PEN WITH STRAW—THE CIDER HOUSE—THE CELLAR—PACKING IN BARRELS—SWEATING—WAXY COATING TO BE PRESERVED—FRUIT-ROOMS—PLANS—NYCE'S PATENT.

Ripening Fruits.—Having succeeded in bringing our trees into a productive condition, we now come to a period of their history which is possessed of great interest to the orchardist. While he is contemplating the rich returns for his capital and labor expended upon the orchard, however, he will find many circumstances in the functions of his plants that will amply repay him for their careful study. Nor should he consider these only as matters of philosophical interest, for they will often lead him into courses of treatment that will enable him to secure richer returns than he would otherwise attain. A few of these will be presented in the commencement of this chapter, nor need any apology be offered for quoting one of the highest authorities in the language upon this branch of botanical study. Balfour gives the following account of the changes which occur in the vegetable economy during the formation and ripening of fruits, under which term he includes, in botanical language, all seeds, whether the dry pericarps, or the pulpy drupes, and other appendages, which are recognized as fruits proper in pomological language.

"While the fruit enlarges, the sap is drawn towards it, and a great exhaustion of the juices of the plant takes place. In annuals, this exhaustion is such as to destroy the plants; but if they are prevented from bearing fruit, they may be made to live for two or more years. Perennials, by acquiring increased vigor, are able better to bear the demand made upon them during fruiting. If large and highly flavored fruit is desired, it is of importance to allow an accumulation of sap to take place before the plant flowers. When a very young plant is permitted to blossom, it seldom brings fruit to perfection. When a plant produces fruit in very large quantities, gardeners are in the habit of thinning it early, in order that there may be an increased supply of sap for that which remains. In this way, peaches, nectarines, apricots, etc., are rendered larger and better flavored. When the fruiting is checked for one season, there is an accumulation of nutritive matter which has a beneficial effect upon the subsequent crop.

"The pericarp is at first of a green color, and performs the same functions as the other green parts of plants, decomposing carbonic acid under the agency of light and liberating oxygen. Saussure asserts that all fruits, in a green state, are adequate to perform this process of deoxidation. As the pericarp advances to maturity, it either becomes dry or succulent. In the former case it changes into a brown or white color, and has a quantity of ligneous matter deposited in its substance, so as to acquire great hardness, where it is incapable of performing any process of vegetable life; in the latter it becomes fleshy in its texture, and assumes various bright tints. In fleshy fruits, however, there is frequently a deposition of ligneous cells in the endocarp, forming the stone of the fruit; and even in the pulpy matter of the sarcocarp, there are found isolated cells of a similar nature, as in some varieties of pear, where they cause a peculiar grittiness. The contents of the cells near the outside of succulent fruits are thickened by exhalation, and a process of endosmose goes on, by which the thinner contents of the inner cells pass outward, and thus cause swelling of the fruit. As the fruit advances to maturity, however, this exhalation diminishes, the water becoming free and entering into new combinations. In all pulpy fruits, which are not green, there are changes going on by which carbon is separated in combination with oxygen.

* * * "Succulent fruits contain a large quantity of water along with cellulose or lignine, sugar, gummy matter or dextrine, albumen, coloring matter, various organic acids, as citric, malic and tartaric, combined with lime and alkaline substances, beside a pulpy gelatinous matter, which is converted by acids into pectine, whence pectic acid is formed by the action of albumen. Pectine is soluble in water, and exists in the pulp of fruits, as apples, gooseberries, currants, strawberries, etc. Pectic acid is said to consist of C.14, H.3, O.12 + H.O. It absorbs water, and is changed into a jelly-like matter, hence its use in making preserves. Each kind of fruit is flavored with a peculiar aromatic substance. Starch is rarely present in the pericarp of the fruit, although it occurs commonly in the seed. * * *

"During the ripening much of the water disappears, while the cellulose or lignine and the dextrine are converted into sugar. Berard is of opinion that the changes in fruits are caused by the action of the oxygen of the air. Freney found that fruits, covered with varnish, did not ripen. As the process of ripening becomes perfected, the acids combine with alkalies, and thus the acidity of the fruit diminishes, while its sweetness increases. The formation of sugar is by some attributed to the action of organic acids on the vegetable constituents, gum, dextrine, and starch; others think that the cellulose and lignine are similarly changed, by the action of acids. The formation of sugar is said to be prevented by watering the tree with alkaline solutions. * * * In seasons, when there is little sun, but a great abundance of moisture, succulent fruits become watery and lose their flavor. The same thing frequently takes place in young trees with abundance of sap, and in cases where a large supply of water has been given artificially." Travelers, who have eaten the magnificent specimens of fruits produced by irrigation, in California, tell us that they are deficient in flavor, and the same thing is sometimes observed as a result of an unusually wet season.

"It is not easy in all cases to determine the exact time when the fruit is ripe. In dry fruits, the period immediately before dehiscence,20 is considered as that of maturation; but in pulpy fruits, there is much uncertainty. It is usual to say that edible fruits are ripe when their ingredients are in such a state of combination as to give the most agreeable flavor. After such are ripe, in the ordinary sense, so as to be capable of being used for food, they undergo further changes by the oxidation of their tissues, even after being separated from the plant. In some cases these changes improve the quality of the fruit, as in the case of the medlar, the austerity of which is thus still further diminished. In the pear, this process renders it soft, but still fit for food, while in the apple it causes a decay which acts injuriously on its qualities. By this process of oxidation, the whole fruit is ultimately reduced to a putrescent mass, which probably acts beneficially in promoting the germination of the seeds when the fruit drops on the ground.

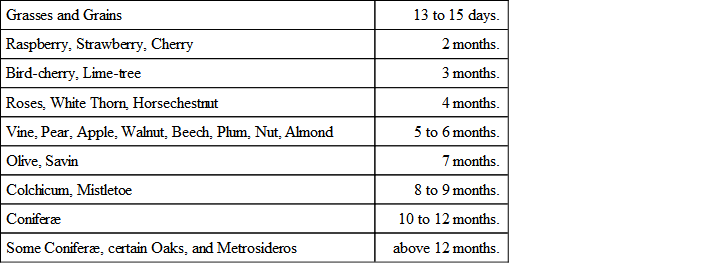

"The periods of time required for ripening the fruit, varies in different plants. Most fruits ripen within a year from the expansion of the flower, some come to maturity within a few days, others require months. Certain plants, as some Coniferæ, require more than a year, and in the Metrosideros the fruit remains attached to the branch for several years. The following is a general statement of the usual time required for the maturation of fruits:—

"The ripening of fruits may be accelerated by the application of heat, the placing of dark-colored bricks below it, and by removing a ring of bark, so as to lead to an accumulation of sap. It has been observed that plants, subjected to a high temperature, not unfrequently prove abortive; this seems to result from the over stimulation, causing the production of uni-sexual flowers alone. Trees are sometimes made to produce fruit by checking their roots when too luxuriant, and by preventing the excessive development of branches."21 Here we have the explanation of the processes of root pruning and of summer pinching, and shortening-in, which have been more extensively introduced upon another page; as well as the plan for inducing fruitfulness in such trees as are tardy from excessive wood-growth, by hacking the bark to interrupt the flow of sap from the buds to the roots; by this, some of the former are changed to flower-buds.

We may learn to judge of the condition of ripeness of our larger succulent fruits, such as apples and pears, by a little experience. When ready to be picked, they will have attained their maximum size, their color will have changed somewhat from its greenness, and they will assume a sort of translucency that indicates the approach of maturity; but the best practical test for the fruit-gatherer, is the ready separation of the stem from its attachment. In those fruits, which are suspended by a stem of considerable length, and in which this organ belongs to the fruit itself, and is intimately connected with its tissues, we shall find that it will part easily from the branch at that period of ripeness when it is best to separate it. Such fruits are often much improved by a continuation of the process of ripening after they are gathered, but this more properly belongs to another division of the subject. There is another class of fruits which are found to attain their greatest excellence and most perfect ripening upon the tree itself, and these can never be enjoyed elsewhere in so great perfection as in close proximity to the place of their production; because, so soon as they are separated from their connection with the plant, a process of decomposition commences, they begin to decay, and many of them soon become really unwholesome. Most of those that are called stone-fruits are of this character, such as peaches, nectarines, apricots, plums, and cherries—all of which have a very transitory period of excellence. The same is still more remarkably the case with most of the berries, hence all of these classes of fruits are better adapted to a near than to a distant market.

With apples and pears, however, the case is quite different. Some of these, it is true, especially some of the summer varieties, will attain a perfect state of ripeness while yet attached to the tree, and some of them will even remain hanging to the twig, until they reach that condition of over-ripeness in which they lose a portion of their fine juices and become mealy, or incipient decay may set in, so as to make them rotten at the core. Hence, in nearly all varieties, it is found best to pluck the fruit a little prematurely, and we are guided by the natural indication of the falling of a portion of the crop. By this means we can, in a degree, control the final ripening of our fruits; and we have the great advantage of being able to ship them in a firm condition to distant markets, so as to arrive at the end of a long journey in prime order; whereas, if thoroughly ripe, they could only be transported a few miles, and then needing the greatest care in their handling. Our summer varieties always require to be near their ultimate ripeness when gathered; for, if plucked too soon, they will wither, and be worthless. Among these, there are some varieties, particularly of the apple, which continue ripening for a long period. In the limited family orchard this quality is a great desideratum in the summer fruits, but it is quite otherwise in the orchards, which are planted for profit in the market, because of the increased expense of gathering only a few at a time repeatedly, instead of clearing the tree at once. It is also found to be an advantage in shipping, to have a considerable quantity of a kind to send off at one time.

Gathering.—We now come to the important matter of harvesting our crops of fruits that have been the cause of so much care and anxiety, as well as of pleasure. This will require new considerations as to its disposition and preservation to the best advantage, and will call for a discussion of the best modes of packing, storing, ripening, and transportation to market.

From what has already been said with regard to the process of ripening of fruits in the natural way upon the tree, it will be understood that we must gather some kinds before they have reached their perfect condition of maturity. There is a point at which they have obtained, from their connection with the parent tree, all the elements that are necessary to the development of their highest qualities. They may now be separated, not only with safety, but with decided advantage in many instances, as they are improved by the further process of maturation under different circumstances from those supplied by nature, and when properly treated, they will acquire a much finer condition as to delicacy and flavor than is ever reached by ripening upon the tree exposed to the light and air. This, it will be remembered, is not the case with all fruits; for, as has already been stated, there are those which must remain upon the tree until they acquire their most perfect ripeness, and which begin to depreciate in quality so soon as they are separated from their connection with the fruit-bearing twig. These need to be at once disposed of, and the consideration of the best means of transportation, is a question of more importance than any plans for their temporary preservation. They must be sold or used at once, and should be handled with the greatest care, packed in suitable boxes or baskets in the most judicious manner for a good display of their beauties, for their preservation from bruising and decay, and for sending them forward to their destination with the least possible delay: the details of these several parts of the business will be left for the exercise of the ingenuity of the parties most deeply interested. In the class of fruits which are so constituted as to bear and indeed to require picking, before they have reached the period of perfect ripeness we shall find several particulars that need consideration. First, it will be found that the proper time for gathering them varies considerably. Thus, with early apples and pears, a few days only embrace the best period, during which they may be gathered without becoming wilted if plucked too soon, or decaying if left too late. Even with winter fruits, we find that, to have them in perfection, some varieties require to be gathered much earlier than the time usually assigned for harvesting the general crop. It is somewhat singular also, that this course very considerably extends their time of keeping, and that some of those varieties which would become dry, mealy, and insipid, early in the winter, if gathered too late, will remain sound, firm, plump, and juicy, and retain all their fine flavor through the winter, if they have been taken from the tree at an earlier period of the season. They must be left upon the tree until properly developed, however, and then be carefully kept in a cool apartment.

The usual season for gathering winter fruits is October, before the access of severe frosts, and at a time when the wood-growth for the season has been completed, and the foliage is nearly ready to separate from its attachment to the tree. The fruits will then generally part readily from the twigs, without either breaking them or rupturing the fruit-stem, which should always be preserved, and from the apple especially, it should never be pulled out, as is apt to happen in certain varieties, when proper care is not exercised in picking them. Some of the apples that require to be gathered early, are, the Rambo, Pryor's Red, Hubbardston, Westfield, Rhode Island Greening, several Russets, and all those which evince a tendency to fall prematurely. There are others which may be left to a later period with impunity, some of these will even bear a little freezing without serious damage, but we should always endeavor to anticipate the exposure of our fruits to any great depression of temperature while they remain attached to the trees. An early and severe frost has often proved disastrous to a fine crop of apples, thus left too long upon the trees.

For all fruits it is essential that the weather should be fine at the time they are gathered. They should be perfectly dry when plucked, and they must be handled with the greatest care to avoid bruising in the slightest degree. Each specimen must be taken separately in the hand and turned to one side, when, if it do not part readily from the twig, the thumb and finger must be applied to the stem, to aid the separation at the proper point; each is then to be placed in a gathering basket, which should be shallow, and for delicate sorts should be lined loosely with fresh leaves or with soft moss, or a little wilted grass. From the baskets, the fruit should be transferred to its permanent winter quarters, by a careful and judicious hand, who should select them and reject all that are bruised, specked, or otherwise defective, and place them on the shelves, or pack them in the boxes or barrels into which they are placed for preservation, or transportation to market. In packing, it is best to use no material but the fruit itself, which should be so closely placed that they shall not jostle and bruise one another when moved. Some persons use a bag, slung around the neck, when gathering the fruits from the tree; into this they are placed as fast as they are plucked, and successively transferred to the barrels, or poured in piles upon the ground. With very firm varieties, this may be done without serious damage, but the bruising that necessarily ensues will be very prejudicial to all the more delicate fruits, and will materially depreciate the value of such as are also of a pale color. A want of care in this matter of handling fruit is, no doubt, the chief reason for the popular preference of red apples in our markets, since those, that are well covered with a deep color, do not show the bruises that are so unseemly upon the fair cheek of the lighter colored varieties.

The modes of keeping winter fruits are exceedingly various, and some of them are quite primitive. The desiderata are coolness and dryness, which should not be carried to the extent of freezing, nor of desiccation. The simplest method is to place the fruit in a pile upon a dry piece of ground, to cover it thickly with clean dry straw, and, as the winter approaches, to apply a heavy layer of earth, sufficient to keep out the frost. Sometimes this is kept from the straw by a simple roof of boards, which support the earth from pressing upon the fruit, and leave it in a sort of cave, which can be entered occasionally during the winter. This plan is only recommended for those who have no cellars or other suitable apartments, for many fruits acquire an earthy flavor from this near contact with the soil. Another primitive plan, and one which is well adapted to the preservation of cider apples, and might be used for the keeping of those needed for stock feeding, is to build a rail-pen, four square, like a field corn-crib, into which the fruit is put upon straw, and a lining of the same material is placed at the sides and upon the top, which may also be sheltered with boards to shed off the rain. In our mild winters, many varieties of fruits can be sufficiently well preserved in this manner for the purposes mentioned. In a proper establishment for cider-making, large bins and rooms are provided within the building, which afford sufficient protection from the frost, so that cider-making may be carried on during the winter; and in well arranged farm-steads, the feeding barns should be provided with suitable compartments for the safe storage of fruits or roots, that are to be fed to the stock during the inclement season, when they are so much needed.