полная версия

полная версияThe Churches and Modern Thought

P. 124, line 1.—Buddha was miraculously born.

Maya dreams that she is carried by archangels to heaven, and that there the future Buddha enters her right side in the form of a superb white elephant. Rhys Davids relates this legend on p. 183 of his Buddhism, and in a footnote he says: “Csoma Korösi refers in a distant way to a belief of the later Mongol Buddhists that Maya was a virgin (As. Res. xx. 299); but this has not been confirmed. St. Jerome says (Adversus Jovin., bk. 1): ‘It is handed down as a tradition among the Gymnosophists of India that Buddha, the founder of their system, was brought forth by a virgin from her side.’” In Samuel Beal’s Romantic History of Buddha (from the Chinese version) we read of Buddha’s miraculous birth, and that there is ground to assume the prevalence of this belief for centuries before Christ. Bunsen, again (p. x. of his Angel-Messiah), speaks of the “Virgin Maya, on whom, according to Chinese tradition, the Holy Ghost had descended”; and elsewhere (e.g., pp. 10 and 25) he adopts this version of the legend. Dr. Knowling, in his apologetic work, Our Lord’s Virgin Birth and the Criticism of Today, pp. 53–4, lays stress upon the grotesqueness of the idea that a man should enter his mother’s womb in the form of a white elephant. But, as Dr. Rhys Davids explains (p. 184 of Buddhism), there is nothing bizarre when the origin of the poetical figure has been ascertained. The belief was borrowed from the older sun-worship, “the white elephant, like the white horse [cf. Rev. vi. 2 and xix. 11, 14], being an emblem of the sun, the universal monarch of the sky.”

P. 126, lines 1–2.—He was very early regarded as omniscient and absolutely sinless.

Dr. Rhys Davids’s remarks on the early growth of myths concerning Buddha, coming as they do from a champion of the Christian cause, are full of significance for anyone who permits himself to think and who keeps an open mind. He says (p. 182 of Buddhism): “The belief soon sprang up that he could not have been, that he was not, born as ordinary men are; that he had no earthly father; that he descended of his own accord into his mother’s womb from his throne in heaven; and that he gave unmistakeable signs, immediately after his birth, of his high character and of his future greatness.”

We have a perfect illustration of the possibility and rapidity of the legend-making process in the nineteenth century. The Bab (or “gateway”) was a Persian reformer who suffered martyrdom at the hands of the authorities in 1850. Within forty years an evidently mythical version of his life was current among his followers in the form of a Gospel. Babism inculcates a high morality, and there is a likelihood of its becoming paramount in Persia. For further information on this new religion see Life and Teachings of Abbas Effendi, by Myron H. Phelps (Putnam).

P. 127, line 10.—Born of the Virgin Isis.

It is true, as Dr. Knowling points out (p. 56 of The Virgin Birth), and as I have personally seen, that in the inscriptions and scenes in the temple of Luxor “we have at least some elements of the glorifying of sensual desire which is so far removed from the chaste restraint and simplicity of the Evangelists.” But the parallel is not a whit the less admissible because the same story appears in a fresh garb to suit the higher ideals of a new religion.

P. 130, note 1.—Mexican Antiquities.

Most of Viscount Kingsborough’s life and fortune was devoted to his illustrated work, Antiquities of Mexico (nine volumes and a portion of a tenth volume, imperial folio, London, 1830–48). No anti-Christian spirit inspired his labours; on the contrary, he attempted to prove a Jewish migration to Mexico. Though the attempt failed, he bequeathed to posterity an invaluable work on the ancient religion of Mexico.

P. 131, line 26.—Healing miracles, such as those performed by Jesus.

Conyers Middleton, formerly principal librarian of Cambridge University, tells us that in the temples of Æsculapius all kinds of diseases were believed to be publicly cured, by the pretended help of the Deity, in proof of which there were erected in each temple columns of brass or marble, on which a distinct narrative of each particular cure was described. There is a remarkable fragment of one of these tables still extant, and exhibited by Gruter in his collection (just as it was found in the ruins of the temple of Æsculapius in the Tiber island), which gives an account of two blind men restored to sight by Æsculapius, in the open view, and with the loud acclamation of the people, acknowledging the manifest power of the god. Compare St. Matthew ix. 27–30. Is it not truly marvellous to think that exactly the same sort of thing is going on at the various miracle-working shrines of Christendom at the present moment? Is it not also surprising to hear certain divines in our own country speak of the alleged miracles of the early Church as if they were real, and as if it were a sort of lost art due to our poorer faith in modern times? I am referring to sermons preached lately from various pulpits on the subject of Christian Science and Faith-cures.

P. 133, line 20.—Acted in Athens five hundred years before the Christian era.

In the Nineteenth Century for March, 1905, Mr. Slade Butler points out, in his article on “The Greek Mysteries and the Gospel Narrative,” that in the first century after Christ these mysteries, in one form or another, had become the recognised religion of the Greek world. Mr. Butler takes in turn all the main features of the Gospel narratives, and shows their close resemblance to incidents of the Greek mystery-dramas. The baptism of John, the triumphal procession in honour of Jesus, His clearing of the temple, the cursing of the fig tree, the Last Supper, the mocking of Jesus in His death-agony, are shown to have striking parallels in the sacred mysteries of the Greeks.

P. 133, line 23.—Even Bacchus … was a slain Saviour.

Dupuis, The Origin of all Religious Worship, pp. 135 and 258; Higgins, Anacalypsis, vol. ii., p. 102; Knight, The Symbolical Language of Ancient Art and Mythology, p. xxii., note, and p. 98, note.

P. 134, lines 7–8.—Pagan crucifixions of the young incarnate divinities of India, Persia, Asia Minor, and Egypt.

We have it on the authority of a Christian Father that the Pagans adored crosses; for Tertullian, a Christian Father of the second and third centuries, writing to the Pagans, says: “The origin of your god is derived from figures moulded on a cross” (Apol., chap. xvi.; Ad Nationes, chap. xii.). At the present moment, both in Europe and America, the Egyptian cross or “life” sign is a fashionable ornament, under the name of crux ansata (or cross with a handle). Its pious wearers are, of course, quite unaware that it is the phallic emblem! Could anything more conclusively demonstrate the prevailing ignorance of comparative mythology?394

P. 138, note.—The probable date of the origin of the story [of Buddha, Chinese version].

“A very valuable date, later than which we cannot place the origin of the story, may be derived from the colophon at the end of the last chapter of the book. It is there stated that the Abhinish Kramana Sûtra is called by the school of the Dharmaguptas Fo-pen-hing-king.... We know from the ‘Chinese Encyclopædia,’ Kai-yuen-shi-kian-mu-lu, that the Fo-pen-hing was translated into Chinese from the Sanscrit (the ancient language of Hindostan) so early as the eleventh year of the reign of Wing-ping (Ming-ti), of the Han dynasty—i e., 69 or 70 A.D. We may therefore safely suppose that the original work was in circulation in India for some time previous to that date.” (Quoted from the Introduction to Mr. S. Beal’s Romantic History of Buddha.) Thus, as the writer of the article on the Gospels in the Enc. Bib. observes, when referring to the parallels: “The proof that the Buddhistic sources are older than the Christian must be regarded as irrefragable.”

P. 148, line 21.—Modern non-Christian beliefs, Parallels in the rites of.

Very similar ceremonies are to be found among the heathen to-day. For instance, something very like our Eucharistical rite is performed in modern Japan. Looking on at a service in a Shinto temple, I was much struck by the extraordinary similarity of the whole ceremony. It was a sort of High Mass with Gregorian music. The blessed wafers are not eaten on the premises, but are taken away by the worshippers to be used in time of sickness. The worshippers, I may mention, were all of the poorer and more ignorant classes.

P. 150, line 10.—Their blood was drunk in the form of wine.

Regarding this, Mr. Grant Allen remarks: When Dionysus became the annual or biennial vine-god victim, “it was inevitable that his worshippers should have seen his resurrection and embodiment in the vine, and should have regarded the wine it yielded as the blood of the god.”

P. 156, lines 19–20.—Adopting their dates for the birth and death [and resurrection] of their Saviours.

At the winter solstice the sun seemed to the ancients to be commencing its annual journey round the heavens. Accordingly, December 25th was considered to be the sun’s birthday, which was annually celebrated by a great festival in many parts of the heathen world—in China, India, Persia, Egypt, and also in ancient Greece, Rome, Germany, Scandinavia, Great Britain, Ireland, and America. Similarly, at the vernal equinox, the sun, which has been below the equator, suddenly appears to rise above it, and so, usually upon a date calculated by the pagan astronomers (and corresponding roughly to our Easter), we find that throughout a considerable portion of the ancient world, after mourning the sun’s death (sometimes for a period of three days), the Resurrection was celebrated with great rejoicings. Primitive man regarded all sensible objects as instinct with a conscious life. He noted the changes of days and years, and the objects which so changed were to him as living things. The rising and setting sun, the return of summer and winter, became a drama in which the actors were his friends or enemies. It was no allegory, but, strange as it appears to us now, all an absolute reality.

Christ’s birth was ultimately placed at the winter solstice, the birthday of the sun-god in the most popular cults; and, while that is fixed as an anniversary, the date of the Crucifixion is made to vary from year to year in order to conform to the astronomical principle on which the Jews, following the sun-worshippers, had fixed their Passover. This ignorance of the early Church concerning the dates of the Jesus’ birth, death, and “resurrection,” is an exceedingly suspicious circumstance. If the fundamental verities were an objective fact to the early Christians, how could the dates have been so utterly forgotten that dates belonging to idolatrous superstitions had to be adopted? It is perplexing enough that God should have allowed the memory of His Son’s life on earth to be handed down for a considerable time by tradition only; but that He should have permitted such lapses of memory and the substitution of the dates of pagan festivals is to me altogether inconceivable. It could not but raise suspicion concerning His revelation in future thinking generations. We have a certain knowledge of the dates of comparatively unimportant events in the world’s history, ages before the Christian era. If these important dates could be forgotten, what else may not have been forgotten; what else may not have been substituted in the place of forgotten incidents? Again, did not the disciples and their converts celebrate the anniversaries of these great events? And, if so, on what dates? The question is of more importance than perhaps at first sight it appears to be. The public will soon be asking the Church for a satisfactory explanation, and she must be prepared to furnish it. In the Daily Telegraph, during the Christmas of 1904, the public were informed that “the most erudite archæologists and professors of Church history confess that there is not a particle of evidence, either Biblical or traditional, for the claim of December 25th to be the birthday of Christ, and that everything goes to prove that our existing festival of the Nativity was introduced to replace the heathen festival of the ‘sol invictus’ in Southern Italy, and of the Yule or Winter solstice festival among the ancient Teutons.” Again, in the Daily Graphic during the Easter of 1905, the public will have read that “there is no particular sanctity in the ‘Table to Find Easter,’ based as it is upon the calculations of a pagan astronomer who lived four hundred years before Christ.” In France the Christian names of the four statutory holidays have been abolished by law. Christmas is called the Festival of the Family, and so on. The time is coming, and is even now at hand, when the English public will discover ugly facts about Christianity without having to read books published by freethinking firms—books which the parson advises us to leave severely alone.

P. 160, lines 3–4.—Why do we hear so little of this great discovery from the pulpit?

The following from a sermon by the Bishop of Manchester, preached in Manchester Cathedral on Sunday, September 4th, 1887, forms a striking exception to the rule. “The sufficient answer,” says the Bishop, “to ninety out of a hundred of the ordinary objections to the Bible, as the record of a divine education of our race, is given in that one word—development. And to what are we indebted for that potent word, which, as with the wand of a magician, has at the same moment so completely transformed our knowledge and dispelled our difficulties? To modern science, resolutely pursuing its search for truth in spite of popular obloquy and—alas that one should have to say it—in spite too often of theological denunciation!” (Quoted by Professor Huxley in his essay on “An Episcopal Trilogy.”) Would that there were equal candour all round! But this indebtedness of theology to science in spite of itself is certainly one of the many workings of the Holy Spirit which are quite inexplicable. All the more so when we remember that truth-seeking scientists are, nowadays, usually Agnostics.

P. 165, lines 38–9.—A Mithraist could turn to the Christian worship and find his main rites unimpaired.

We have the witness of the Christian Fathers. Justin Martyr, after describing the institution of the Lord’s Supper (1 Apol., chap. 66), goes on to say: “Which the wicked devils have imitated in the mysteries of Mithra, commanding the same thing to be done. For that bread and a cup of water are placed with certain incantations in the mystic rites of the one who is being initiated, you either know or can learn.” Tertullian intimates that “the devil, by the mysteries of his idols, imitates even the main parts of the divine mysteries. He also baptises his worshippers in water, and makes them believe that this purifies them of their crimes. There Mithra sets his mark on the forehead of his soldiers; he celebrates the oblation of bread; he offers an image of the resurrection, and presents at once the crown and sword; he limits his chief priest to a single marriage; he even has virgins and his ascetics (continentes).” (Præscr. c. 40. Cp. De Bapt. c. 5; De Corona, c. 15. Quoted on p. 322 of J. M. Robertson’s Pagan Christs.) We have also the witness of modern discoveries. For example, Professor Franz Cumont, in his work, Les Mystères de Mithra, gives a photograph of a recently-discovered bas-relief, representing a Mithraic communion. On a small tripod is the bread, in the form of wafers, each marked with a cross.

Chapter VP. 172, lines 14–15.—Ignorance of the gist of the Darwinian theory, “natural selection,” has been fruitful in misunderstandings.

It is very necessary to understand exactly what the theory of natural selection is and is not; because champions of the Faith, even when believing in Evolution, base some of their arguments on the alleged collapse of the Darwinian theory. Thus, in Present-day Rationalism Critically Examined, the Rev. Professor George Henslow affirms that, while the theory of Evolution stands on an impregnable basis, Haeckel’s Monism and Rationalistic agnosticism are based on Darwin’s doctrine of natural selection, and he enters upon an elaborate argument—covering sixty pages of his book—to show that the origin of species by means of natural selection is false, and that the primary cause of Evolution is the definite action of the environment, combined with the adaptive powers of the living organism. Such arguments, coming from a clergyman having scientific attainments, are likely to impress the average Christian reader and confuse the main issue. Natural selection is “the action of the environment” (see The Origin of Species, chap. iv.), and even if it were not, and if natural selection (or elimination) were not the primary cause, the doctrine of the action of environment will suit the Monist just as well.

Regarding the minor, but not unimportant, part played by sexual selection, Darwin writes: “For my own part, I conclude that of all the causes which have led to the differences in external appearance between the races of men, and to a certain extent between man and the lower animals, sexual selection has been by far the most efficient” (Descent of Man, ed. 1871, ii., 367).

Scientists who are advocates of the Christian cause are not always as candid as one could wish. While the Church cited Sir Richard Owen “as an authority against the Darwinian theory, especially in its application to man’s descent, there remained in the memory of his brother savants his lack of candour in never withdrawing the statement made by him, and demonstrated by Huxley as untrue, that the hippocampus minor in the human brain is absent from the brain of the ape.” (See p. 172 of Mr. Clodd’s Pioneers of Evolution. See also remarks by Sir Charles Lyell, pp. 485 and 486 of his work, Antiquity of Man. On p. 290 he further tells us that “we may consider the attempt to distinguish the brain of man from that of the ape on the ground of newly-discovered cerebral characters, presenting differences in kind, as virtually abandoned by its originator.”)

P. 205, lines 18–20.—That there are not more links missing is due principally to the discovery of fossil remains.

The greatest importance has been attached to a discovery in Java, made in 1894 by Eugene Dubois. The remains consisted of the crown of the skull, two teeth, and a femur belonging to a creature for which the name Pithecanthropus erectus has been invented. This pithecanthropus excited the liveliest interest as the long-sought transitional form between man and the ape. Professor Haeckel writes concerning this in his book, The Evolution of Man, vol. ii., p. 633: “There were very interesting scientific discussions on it at the last three International Congresses of Zoology (Leyden, 1895; Cambridge, 1898; and Berlin, 1901). I took an active part in the discussion at Cambridge, and may refer the reader to the paper I read there.” (It has been translated by Dr. Gadow, under the title of The Last Link.) Since then we have Professor Keasbey writing in 1901 that the remains have been “pronounced genuine,” and Professor Packard, in 1902, that it is now “generally recognised.”

Again, to give a still more recent “find,” Dr. Andrews, who accompanied the Geological Survey of Egypt, has (as mentioned by Professor Ray Lankester in his lecture at the London Institution on November 2nd, 1906) discovered a remarkable skull (now in the Natural History Museum) which is the connecting link between elephants, ancient and modern, and other mammals.

There have also been discoveries of missing links among the living. The duck-bill, a four-footed animal which lays eggs, is an important link between reptiles and mammals. Cuvier, the celebrated French naturalist, a persistent opponent of the evolutionary doctrines advanced by Lamarck and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, did not believe it possible that any four-footed animal could lay eggs, and it was not till long after his time, and, indeed, only quite lately, that the statements of the natives were verified, and the eggs of the duck-bill actually found.

P. 208, lines 14–18.—Enough has been said, I hope, to convince the reader that … there is overpowering evidence against separate acts of creation, and in favour of an animal origin of the human race.

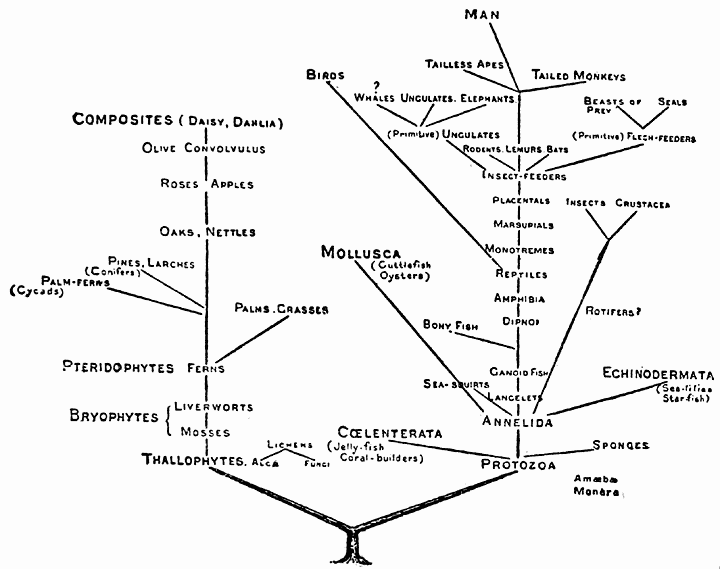

This Family Tree of Life will enable him to form a brain-picture of the various steps in the evolutionary process:—

[Note.—It is now generally admitted that man goes back at least 200,000 years.]

Protoplasm plus Chlorophyll

This diagram of development is taken from Edwards Clodd’s work, The Story of Creation, by the kind permission of Mr. Clodd and Messrs. Longmans.

Note by Mr. Clodd.—The ascent of the higher life-forms from the lower is more lateral than the lines indicate, but the diagram is only a rough attempt to show the relative places of the leading groups.

P. 218, lines 14–15.—The dogmas of sin and its atonement.

“Astronomers tell us that there are some 500,000,000 suns visible from our earth, many if not most of them larger than our sun, and all of them presumably surrounded by planets at least as important as our earth; and to maintain the old theological view of the supreme value of this little insignificant planet in the eyes of the ‘Almighty Ruler’ of such a universe, or to suppose that He would send His ‘Only Son’ to die for us little cosmic microbes, is presumption which, when one thinks of it, really seems to amount to insanity” (quoted from p. 108 of Richard Harte’s Lay Religion).

Chapter VIP. 220, line 1.—Deism denies Christianity.

“God,” says Canon Liddon, “is banished from the world by deism, which puts nature in His place” (Some Elements of Religion, pp. 56–7). The seventeenth and eighteenth-century deists, however, did not deny the personality of God, but the fact of revelation. “In recent theology deism has generally come to be regarded as, in common with theism, holding in opposition to atheism that there is a God, and in opposition to pantheism that God is distinct from the world, but as differing from theism in maintaining that God is separate from the world, having endowed it with self-sustaining and self-acting powers, and then abandoned it to itself” (Enc. Brit., art. “Theism”).

P. 221, line 8.—“What it is to be a Christian.”

Archdeacon Wilson avers that “We dare not deny the name of Christian to such as live in Christ’s spirit and do His will, though they know not for certain how God manifested himself in Christ, and will not profess a certainty they do not feel.” Again, he argues that “We rest on the broad ground of the vast experience of the world, and the testimony of our own conscience, that Christ has lifted mankind up, and shown man what is good; and this we may describe as bringing man to God, and revealing God to man. This redemption, salvation, we acknowledge as a fact. He who has this faith in Christ, and lets it work its natural result in making him more like Christ, deserves to be called a Christian.” This does, indeed, give plenty of latitude—far more, in fact, than the Church as a body seems likely to give for some time to come. It, and the Rev. R. J. Campbell’s “New Theology,” will certainly enable many who are in reality non-Christian theists to continue calling themselves Christians.

P. 224, note.—“Haeckel’s Critics Answered.”

In the chapter on “God” there is a striking exposition of the very latest arguments for and against Theism. The opinions of Messrs. Ward, Newman, Smythe, Le Conte, Fiske, W. N. Clarke, Croll, Aubrey Moore, Iverach, Dallinger, Ballard, Rhondda Williams, Profeit, Kennedy, W. James, and Royce are all considered. Many pious Christians may have read the apologists’ criticisms of Haeckel’s well-known work, The Riddle of the Universe, but few will have studied the work itself, and still fewer these clear and convincing replies to the criticisms. It cannot be on account of the cost, as a copy of the cheap edition of either of these works can be obtained for 4½d.