полная версия

полная версияA July Holiday in Saxony, Bohemia, and Silesia

Beech woods adorn this part of the country, and relieve the dark slopes of firs which here and there border the landscape; and everywhere you see signs of careful cultivation. After passing Bernsdorf—a village on the high road to Trautenau—I fell in with a weaver, and we walked together to Altendorf. A right talkative fellow did he prove himself; a barefoot philosopher, clad in a loose garment of coarse baize. He lived at Kunzendorf, where he kept his loom going while work was to be had, and, when it wasn't, did the best he could without. Thought a dollar a week tidy wages; a dollar and a half, jolly; and two dollars, wonderfully happy. Never ate meat; never expected it, and so didn't fret about it. Bread, soup, and a glass of beer at the Wirthshaus in the evening, was all he could get, and a weaver who got that had not much to complain of. All this was said in a free, hearty tone, that left me no reason to doubt its sincerity.

The country was no longer what it had been. Twelve years ago the land to the right and left, all the way from Schatzlar, was covered with forest; now it was all fields, and every year the fields spread wider, and up the hills; and though firewood was dearer, potatoes, beetroot, and rye were more plentiful; and that seemed only fair, because every year more mouths opened and wanted food.

For every cottage we passed my philosopher had a joke; something about the bees' humming-tops, or frogs' hams, that sent the inmates into roars of laughter. I invited him to eat bread and cheese with me at Altendorf: he stared, gave a whoop of surprise, and accepted. Of all the large rooms I had yet seen in a public-house the one in the Wirthshaus here was the largest; spacious enough for a town-hall. The groined and vaulted ceiling rests on tall, massive pillars; four chandeliers hang by long strings; in one corner stands a two-wheeled truck; an enormous bread-trough; platter-shaped baskets filled with flour, and a mountain of washing utensils. Trencher-cap brought us two glasses of beer—tall glasses, to match the room, vase-like in form, and fifteen inches high at least. The beer was of the colour of porter, and, as I thought, of a very disagreeable flavour; but the weaver took a hearty pull, smacked his lips, and pronounced it better than Bavarian, or Stohnsdorfer, or any other kind. That was the sort they always drank at Kunzendorf, and wholesome stuff it was; meat and drink too. He emptied my glass after his own—for one taste was enough for me—and then, as he bade me good-bye, and went his way, he expressed a hope that he might meet with an Englishman every time he took the same walk.

From Altendorf a short cut by intricate paths over a wooded hill saves nearly two miles in the distance to Adersbach. It is a pretty walk, up and down slopes gay with loosestrife—Steinrosen, as the country folk call it—and among rocks, of which one of the largest is known as the Gott und Vater Stein. You emerge in a shallow valley, at Upper Adersbach, and follow the road downwards, past low-shingled cottages, the fronts coloured yellow with white stripes, the shutters blue, and all the rearward portion showing white stripes along the joints of the old dark wood, and crossing on the ends of the beams. The eaves are not more than six feet from the ground, so that where the house stands back in a garden, it is half buried by apple-trees and scarlet-runners, and the cabbages and flowers look in at the windows. The people are as rustic as their dwellings. Ask a question, and a blunt "Was?" is the first word in answer; no "Wie meinen sie?" as in other places. Good Papists, nevertheless, for they stop and recite a prayer before one of the gaudy crucifixes, which, surrounded by angels bearing inscribed tablets, or ornamented by pictures of the Virgin and St. Anne, stand within a wooden fence at the roadside here and there along the village.

The valley narrows, and presently you see strange masses of stone peering from the fir-wood on the right, more and more numerous, till at length the rock prevails, and the trees grow only in gaps and clefts. The masses present astonishing varieties of the columnar form, some tall and upright, others broken and leaning; and looking across the intervening breadth of meadow, you can imagine doorways, porticos, colonnades, and grotesque sculptures. Here and there, fronting the rest, stands a semicircular mass, as it were a huge grindstone, one half buried in the earth, or a pile that looks like a weatherbeaten, buttressed wall; and, raised by the slope of the ground, you see the tops of other masses, continuing away to the rear.

The spectacle grows yet more striking, for the height and dimensions of the rocks increase as you advance. About a mile onwards and a short range of similar rocks appears isolated in a wood on the left. Here a whitewashed gateway bestrides the road—the entrance to the Gasthaus zur Felsenstadt (Rock-City Inn), resorted to every year by hundreds of visitors.

Old Hübner was clearly mistaken. In seven hours of easy walking I had accomplished the distance from Grenzbäuden, and was ready, after half an hour's rest, to explore the wonders of Adersbach.

The custom of the place is, that you shall take a guide whether or no, pay him a fee for his trouble, and another for admission besides; and to carry it out, a staff of guides are always at the service of visitors. Their costume is the same as that of the mountain guides—boots, buttons, hat and feather, and velveteen. You may wait and join a party if you like: I preferred going alone.

The meadow behind the house is planted with trees forming shady walks. Here the guide calls your attention to two outlying masses, one of which he names Rubezahl, the other the Sleeping Woman. He talks naturally when he talks, but when he describes or names anything he does it in the showman's style—"Look to the left and there you see Admiral Lyons a-bombardin' of Sebastopol," &c.; and so frequent and sudden were these changes of voice and manner, that at last I could not help laughing at them, even in places where laughter was by no means appropriate. We crossed the brook—Adersbach—to an opening about forty feet broad, which forms an approach to the Rock City that makes a deep impression on you, and excites your expectations. It is an avenue bordered on either side by the remains of such buildings and monuments as we saw specimens of in the mountains on our way hither, only here the Cyclopean architects worked on a greater scale, and crowded their edifices together. Here, indeed, was their metropolis; and this the grand entrance, where now vegetation clothes the ruin with beauty.

The road is soft and sandy: everywhere nothing but sand underfoot. The objects increase in magnitude as we proceed. Great masses of cliff look down on us, their sides and summit clothed with young trees—beech, birch, fir, growing from every crevice. The sand accumulated round their base forms a broad, sloping plinth, overgrown with long grass, creeping weeds, and bushes, through which run little paths leading to caverns, vaults, and passages in the rock. Some of the caverns are formed by great fragments fallen one against the other; some in the solid rock have the smooth and worn appearance produced by the action of the water, as in cliffs on the sea-shore; the galleries and passages are similarly formed; but here and there you see that the mighty rock has been split from head to foot by some shock which separated the halves but a few inches, leaving evidence of their former union in the corresponding inequalities of the broken surfaces.

Presently we step forth into a meadow from which a stripe of open country undulates away between the bordering forest. Here, where the path turns to the left, you see the Sugarloaf, a huge detached rock some eighty feet high, rising out of a pond. Either it is an inverted sugarloaf, or you may believe that the base is being gradually dissolved by the water. Here, contrasted with the smooth green surface, you can note the abrupt outline of the rocks and its similarity to that of a line of sea-cliffs. Here are capes, headlands, spits, bays, coves, basins, and outlying rocks, reefs, and islets; but with the difference that here every crevice is full of trees and foliage, and branches overtop the crests of the loftiest.

As yet we have seen but a suburb; now, having crossed the meadow, we enter the main city of the rocky labyrinth, and the guide, ever with theatrical tone and attitude, sets to work in earnest. He points out the Pulpit, the Twins, the Giant's Glove, the Chimney, the Gallows, the Burgomaster's Head; and bids you note that the latter wears a periwig, and has a snub nose. Some of these are close to the path, others distant, and only to be seen through the openings, or over the top of the nearer masses. The resemblance to a human head is remarkably frequent, always at the top of a column. I discovered Lord Brougham's profile, and advised the guide to remember it for the benefit of future visitors.

Now the rocks are higher; they crowd close on the path, and presently we come to a narrow passage through a tremendous cliff, where further progress is barred by a door. And here you discover the use of the guide. Before unlocking, he holds out his hand for the twenty-kreutzer fee, which every one must pay for admittance; his own fee will be an after consideration. He then shows you the figure of a Whale in the face of the cliff on the left, then you cross the wooden bridge, and are locked in, as before you were locked out. There is, however, a free way through the water. The little brook that flows so prettily by the side of the path out to the entrance, comes through a vault in the cliff, about thirty yards, and by stooping you can see the glimmer of light from the far end. Three women came that way with bundles of firewood on their backs, and they wade it every time they go in quest of fuel. The water is less than a foot in depth.

The passage is narrow and gloomy between the cliffs. As we emerge, the guide, pointing to a tall rock two hundred and fifty feet in height, names it the Elizabeth Tower of Breslau. Then comes the Breslau Wool-market, from a fancied resemblance in the surrounding rocks to woolsacks. Not far off are the Tables of Moses, the Shameless Maiden, St. John the Baptist, the Tiger's Snout, the Backbone, a long broken column, which forms a disjointed vertebræ. A long list of names might be given were it desirable. For the most part the resemblances are not at all fanciful; in some instances so complete, that you can scarcely believe the handiwork to be Nature's own. She was, however, sole artificer.

We come to a small grassy oasis, where a damsel offers you a goblet of water from the Silver Spring, and invites you to buy crystals or cakes at her stall. The guide shows you the Little Waterfall, a feeder of the brook struggling in a crevice, and conducts you by a steep, rocky path to a cavern into which the Great Waterfall tumbles from a height of about sixty feet. The rocky sides converge as they rise, and leave an opening of a few feet at the apex through which the water falls into a shallow pool beneath. The margin of this pool, a narrow ledge, is the standing-place.

The quantity of water is not great, but it makes a pretty cascade down the rugged side of the darksome cavern. After you have looked at it for a minute or two, the guide blows a shrill whistle, and before you have time to ask what it means, the gloom is suddenly deepened. You look up in surprise. The mouth of the cavern is entirely filled by a torrent which in another second will be down upon your head. You cannot start back if you would; the rock prevents, and in an instant you see that the water makes its plunge with scarcely a splash on the brim of the pool.

Artificial improvement of waterfalls affords me but little pleasure. Here, however, the effect was so surprising that, as the water gleamed and danced in the dusky cavern, and the rushing roar and rapid gurgle at the outlet filled the place with loud reverberations, and the light spray imparted a sense of coolness, I was made to feel there might be an exception.

In our further wanderings we met sundry parties of visitors all led by guides who had the same theatrical trick as mine. You return by the same way to the locked door; but explorations are being made to discover a new route among objects sufficiently striking. Outside the door all is free, and you may roam and make discoveries at pleasure. There are steep gullies which lead into very wild places, where for want of bridges, galleries, and beaten paths, the labour and fatigue of exploration are sensibly multiplied.

In June, 1844, as inscribed on one of the stones, a waterspout burst over Adersbach, and flooded all the tortuous ways among the rocks to a depth of nine feet. Another inscription records the escape of two Englishmen in 1709. They were sheltering from a thunderstorm, when the rock under which they stood was struck by lightning, and the summit shattered without their receiving harm from the falling lumps. Inscriptions of another sort abound—the initials, or entire name and address, of hundreds of visitors, who with chisel or black paint have thought it worth while to let posterity know of their visit to Adersbach. Some ambitious beyond the ordinary, have climbed up thirty or forty feet to carve the capital letters.

CHAPTER XXIII

The Echo—Wonderful Orchestra—Magical Music—A Feu de joie—The Oration—The Voices—Echo and the Humourist—Satisfying the Guide—Exploring the Labyrinth—Curious Discoveries—Speculations of Geologists—Bohemia an Inland Sea—Marble Labyrinth in Spain—A Twilight View—After a'.

"Will it please you to walk to the echo?" asks the guide, when we come back to the meadow. And if you assent—as every one does—he turns to the left and leads you up the open ground above-mentioned to a small temple—the Echo House. You see a man standing near the house playing a clarionet, pausing now and then to recite; but no answering note or word do you hear. But take your seat on the bench against that perpendicular rock on his right, and immediately you hear a whole orchestra of wind instruments among the rocks. Such delicious music! Soft, wild, warbling, rising and falling, melting one into the other in a way that you fancy could only be accomplished by a band of Kobolds with Rübezahl for a leader. And when the player blows short phrases with pauses between, what mocking sprite is that who imitates the sound, flitting from crevice to crevice repeating the tones over and over again, fainter and fainter, till they seem not to die away, but to float out of hearing?

Then his companion comes forward and fires a gun, a signal, so you might believe, for a great discharge of musketry among the rocks, platoon after platoon firing a feu de joie. One—two—three—four! The two men hold up their hands to signify—Listen yet! then comes the rattle of the fifth round from the short range of rocks which we saw on the left while coming down the valley; and the firing commenced by the troops in camp is ended by the outposts.

Then one of the men makes a short oration about the wonders here grouped by which Nature attracts man from afar and fills him with joy and astonishment; voices repeat the oration among the rocks, and then—he comes to you for his fee. For the gunshot the tax is eight kreutzers; and if you give eight more for the music and oration, the two echo-keepers will not look unhappy.

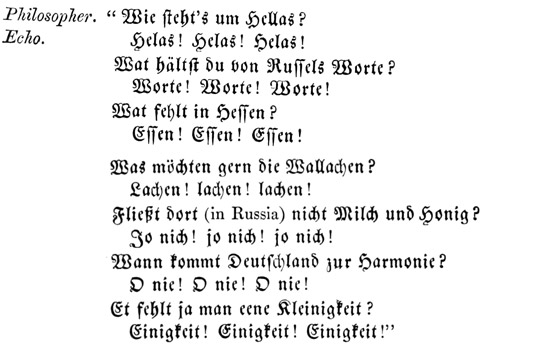

And now, if still incredulous, you may talk to the echo yourself. My test was perfectly convincing, for it woke up a dozen cuckoos among the rocks. When Schulze, the humourist already mentioned, was here, he questioned the mysterious voice concerning political matters, and got unhesitating answers. For example:

Unluckily, the points would all become blunt if translated; I am constrained, therefore, to leave them in the original.

My guide waited to be "satisfied." I asked him what amount of fee he usually received?

"Sometimes," he answered, "I get a dollar."

"But commonly not more than ten kreutzers?"

"M—m—ja, that is true."

"Then what would you say to fifteen kreutzers?"

"Sir, I would say that I wish such as you would come every day to Adersbach."

He left me fully "satisfied." And so, reader, you see that the picturesque is burdened with a tariff in Bohemia as it is in certain parts of England, Scotland, and Wales.

I went back to the rocks. The locked door does not shut in all the wonders, and there are miles which you may explore freely. But unless you stick a branch here and there into the sand, or "blaze" the trees, you will never find your way out again. The great height of the rocks surprises you not less than their amazing number. They are intersected by blind alleys, open alleys, and lanes innumerable, intertwisting and crossing in all directions. Many a cavern, den, and grotto will you see, and many a delightful sylvan retreat, where the solitude is perfect; many a bower which is presently lost. Now you are overcome by wonder, now by awe, for thoughts will come to you of great rock cities and temples smitten by judgments; of the giant race that warred with the gods and were slain by thunder-bolts; of those who worshipped stones and burnt sacrifice on the loftiest rocks.

A few paces farther, and seeing how tall trees grow everywhere among the stony masses, how smaller trees and shrubs shoot from the crevices, and moss enwraps pillar and buttress, and fringes the cliffs, you will think of Nature's silent revolutions; of the ages that rolled away while the labyrinth of Adersbach was formed. Here, so say the geologists, currents of water running for innumerable years, have worn out channels in the softer parts of a wide stratum of sandstone, and produced the effects we now witness. The stratum must have been great, for the rocks extend, more or less crowded, away to the Heuscheuer, a distance of three or four leagues. The mountain itself presents similar phenomena even on its summit.

A supposition prevails, based on much observation, that the whole of Bohemia was once covered by a vast lake, or inland sea. The conformation of the country, its ring-fence of mountains—whence the term Kessel Land (Kettle Land) among the Germans—broken only where the Elbe flows out, while almost every stream within the territory finds its way into that river, besides the fossil deposits so abundantly met with, are facts urged by the learned in favour of their views. It may have been during the existence of this great sea that the rocks were formed.

It might be interesting to inquire whether the rocky labyrinth at Torcal, not far from Antequera, in Spain, presents phenomena similar to those of Adersbach. The rocks, as I have read, are of marble, covering a great extent of ground in groupings singularly picturesque.

It was dusk when I had finished my prowl, for such it was, accompanied by much scrambling. Then I climbed to the top of one of the outlying crags for a view across the maze, and when I saw the numerous gray heads peering out from the feathery fir-tops, here and there a bastion, a broken pillar, and weather-stained tower, the fancy once more possessed me that here was a city of the giants—its walls thrown down, its buildings destroyed, and its rebellious inhabitants turned to stone.

Gradually the hoary rocks looked spectral-like, for the dusk increased, the clouds gathered heavily, and rain began to fall. I walked back to the inn, feeling deeply the force of the Ettrick Shepherd's words, "After a', what is any description by us puir creturs o' the works o' the great God?"

CHAPTER XXIV

Baked Chickens—A Discussion—Weckelsdorf—More Rocks—The Stone of Tears—Death's Alley—Diana's Bath—The Minster—Gang of Coiners—The Bohdanetskis—Going to Church—Another Silesian View—Good-bye to Bohemia—Schömberg—Silesian Faces and Costume—Picturesque Market-place—Ueberschar Hills—Ullersdorf—An amazed Weaver—Liebau—Cheap Cherries—The Prussian Simplon—Ornamented Houses—Buchwald—The Bober—Dittersbach—Schmiedeberg—Rübezahl's Trick upon Travellers—Tourists' Rendezvous—The Duellists' Successors—Erdmannsdorf—Tyrolese Colony.

As Grenzbäuden is renowned for Hungarian wine, so is Adersbach for baked chickens, and every guest, unless he be a greenhorn, eats two for supper. They are very relishing, and quite small enough to prevent any breach of your moderate habit.

Visitors were numerous: some reading their guide-books, some beginning supper, some finishing, some rounding up the evening with another bottle—for Hungarian is to be had in Adersbach. A party near me sat discussing with much animation the demerits of the taxes which impoverish, and of the beggars who importune, travellers around the City of the Rocks, and they drew an inference that the landlord's charges would not be parsimonious. Then they wandered off into the question of temperature—the temperature of Schneekoppe. Not one of them had yet trodden old Snowhead, so they went on guessing at the question, till I mentioned that it had been very cold up there in the morning.

"In the morning! This morning? Heut, mean you?"

"Yes, this very morning; for I was up there."

"Heut! Heut! Heut! Heut!" ejaculated one after another, the last apparently more surprised than the first.

"Yes, this very day."

They would not believe it. I took up a sprig of heather from the side of my plate, which I had gathered on Schwarzkoppe, and showed them that as a token; and explained that the distance was, after all, not so very great, and might have been shortened had I descended directly from the Koppe into the Riesengrund, and laid my course through the village of Dorngrund.

They believed then; but having travelled the road prescribed to me by Father Hübner, could not imagine the distance from the mountain to be but about twenty miles.

By rising early the next morning, when all was bright and fresh and the dust laid by the night's rain, I got time for another stroll among the rocks, and to walk two miles farther down the valley to Weckelsdorf, where another part of the rocky labyrinth is explorable. The rocks here are on a greater scale than at Adersbach, and rising on the slope of a hill, their romantic effect is increased, as also the difficulty of wandering among them. The proprietor, Count von Nummerskirch, has, however, taken pains to render them accessible by bridges, galleries, and stairs. A sitting figure, whose head-dress resembles that of the maidens of Braunau, is named the Bride of Braunau; near her is the Stone of Tears; the Todtengasse (Death's Alley) is never illumined by a ray of sunshine; there is the Cathedral, and near it Diana's Bath; and at last the Minster, a natural temple, the roof a lofty pointed arch, where, while you walk up and down in the dim light, an organ fills the place with a burst of sound. It is sometimes called the Mint, or Money Church, because of a gang of coiners having once made it their head-quarters. The rocks have been a hiding-place for others as well as rogues. During the Hussite wars, many families found a refuge within their intricate recesses, little liable to a surprise, at a time when entrance was hardly possible owing to the numerous obstructions.

As at Adersbach, there is a fee to pay for unlocking a door; there is an echo which answers the guide's voice, his pistol and horn, and has to be paid for. Nevertheless, you will neither regret the outlay of time and kreutzers in your visit to Weckelsdorf. If able to prolong your stay, you may take an excursion of a few hours to the Heuscheuer, and see a smaller Adersbach on its very summit—the highest of these extraordinary rock-formations. Or there is the ruin of Bischoffstein, within an easy walk, once the stronghold of the Bohdanetski family, who held half a score of castles around the neighbourhood, and made themselves obnoxious by their Protestantism and robberies, and envied for their wealth. They suffered at times by siege and onslaught from their neighbours, and at length their castles were demolished, and forty-seven Bohdanetskis and adherents were hanged by the emperor's command. The rest of the family, it is said, took flight, and settled in England. Is Baddenskey, who sits wearily at his loom down there in joyless Spitalfields, a descendant?