полная версия

полная версияA July Holiday in Saxony, Bohemia, and Silesia

And while the light strengthened, there stretched towards the west the mighty shadow of the mountain itself, eclipsing acres of the landscape, which lay dim between the streaming radiance rushing to an apex on either side. But the sun mounts apace, and the shadow grows shorter continually.

The number of cone-like hills is remarkable, and here and there you see one of those circular, flat-topped elevations bristling with dark woods, which characterize much of Bohemian scenery along the Saxon frontier. While gazing on the singular forms, you may imagine them to be the crumbling remains of stupendous columns erected by giant hands in the old primeval ages.

In the distance you see the Elbe, a long, pale stripe, resembling a narrow lake, and you wish there were more of it, for the want of water is a sensible defect in the view. The region is fruitful and well peopled: had it a few large lakes besides, your eye would roam over it with the greater pleasure. The expanse is wide. In very clear weather, so mine host assured me, you can see Prague, and Schneekoppe in the Riesengebirge, each fifty miles distant.

To enable you to get the view all round clear of the trees a circular wooden tower is built, from the platform of which you may gaze on far and near. Immediately beneath you look down into the walled enclosure, upon the huts, the flower-beds, the potato plot, the sheltering hazel copse, and all the ins and outs of the place. You see mossy arbours open to the south, and little nooks where you may recline at ease and contemplate different points of the view.

I was glad after awhile to take refuge in one of these nooks, for the wind blew so strong and keen that my teeth chattered as I walked round the platform. However, there is steaming coffee ready to fortify you against the influences which mar the poetry of sunrise.

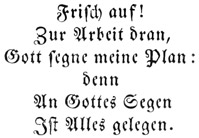

The garden, sheltered by its wall and screen of hazel, teems with flowers, a pleasing sight as you go and come in your explorations. I surveyed the whole premises from the dairy to the dancing-floor; noted the inscriptions here and there with which the owner seeks to conciliate your good opinion; looked at his bazaar, where you may buy Recollections of the Milleschauer, and so round to the little altar under the bell. Here the inscription runs:

Two hours passed. I took a farewell view under the broad sunlight, and then, having to meet a steamer at Lobositz, strode merrily down the hill. What a pleasant walk that was! Once below the summit, among the trees, and the temperature was that of a summer morning; and the woods looked glorious, fringed with light reflected from millions of raindrops—memorials of the former evening's storm, now become things of beauty. Beech, birch, and hazel, intermingled with larch and fir, robe the hill from base to cope, through which the path descends with continued windings; an ever-shifting aisle, as it seems, overarched by green leaves, among which you hear the gladsome chirp and warbling of birds. All the breaks and hollows which appeared so grim and gloomy the night before, the mouths of yawning caverns, now open as narrow glades or twinkling bowers, in which a thousand lights dart and quiver as the cheerful breeze sweeps through, caressing the leaves. Such a walk favours cheerful meditation, and prepares your heart for cloudy weather and dreary prospects; and in after days many a thought born within the wood flits back on the memory.

It was like having been robbed of something to step out of the woods upon the rough grassy slopes at the foot of the hill, and presently to tramp along a hard, beaten road. However, there was the sight of the lofty cone rising in its forest vesture high into the sunlight for repayment; and the lively breeze ceased not to blow.

The ill-favoured clerk at Prague had refused to accredit me beyond Lobositz, so here at nine o'clock I had to go to the Bezirksamt for another visa. Again did I request that the name of some place at the foot of the mountains, or beyond the frontier, might be inserted; but no! I was going a trip down the Elbe, with intention to disembark at Tetschen, so for Tetschen the visa was made out, and the clerk, who was very polite, wished me a pleasant journey.

I found a number of passengers waiting at the river side, reclining on the grass or strolling among the trees. Presently came a large flat boat and conveyed us all to an island, where, by the time we had assembled on the rude landing stage, the steamer Germania arrived and took us on board; not without difficulty, for the deck was literally choked with queer-looking people and rubbishy baggage. What could such a company be travelling for? Wedged in among them sat a party of wandering musicians, men and women, with harps, guitars, fiddles, and flute: the space all too narrow for their movements. However, as soon as the vessel resumed her course down the rapid stream they began to play, and kept up a succession of airs that seemed to convert the exhilarating motion, the breeze and the sunshine into frolicsome music.

I got a seat on the top of a heap of bundles, with clear outlook above the heads of the crowd. It was a delightful voyage, between scenes growing more and more romantic at every bend of the river. Now we shoot past scarped hills, split by narrow gullies dark with foliage, from whence little brooks leap forth to the light; now past sheltered coombs where rural homesteads nestle, and vines hang on the sunny slopes; now past variegated cliffs, all ochre and gray, that come near together, and compel the stream to swerve with boiling eddies and long trains of impatient ripples; now past fields and meadows where the retiring hills leave room for fruitful husbandry, and from far your eye catches the speck of colour—the red or blue petticoats of the women around the hay-wagons.

And along the road which skirts the shore there go men and women, horses and vehicles, and there is always something strange to note in costume and appearance. And close by runs the railway, its course marked by the painted wicker balloons hanging aloft on the signal posts, and the bright colour of the jutting rocks through which the way is hewn, or by a train dashing past with echoing snort and tail of cloud.

The hills crowd closer and higher at every bend. Here and there rises a cliff forming an imposing palisade of rock; then comes a wild mass of crags backed by woods that screen a little red-roofed chapel perched high aloft; then the tower of Schreckenstein comes into view, crowning a tall, gray buttress, which gives a finishing touch to the picturesque.

My attention was diverted from the scenery by a leaf of music held out by one of the musicians. Who could refuse a fee for such strains as theirs? Kreutzer after kreutzer, a few small silver coins, and two or three twopenny bank-notes were dropped into the receptacle, which was presently emptied into the ready hands of the fluteplayer. He counted, shook his head, and saying, "Not enough yet!" gave the signal for a fresh burst. Now came forth music singularly wild and inspiriting—the reserve, perhaps, for an emergency—and none within hearing could resist its influence. Had there been room, every one would surely have danced; as it was, eyes sparkled, heads wagged, and fingers snapped, keeping time with the measure. There seemed something magical about the leader, and I could not help fancying that her fiddle began to speak before the bow had touched the strings. They speak wisely who bid us go to Bohemia for music.

The leaf went round once more, and not in vain; but the fluteplayer still shook his head, whereupon a song and a duet were sung; and then the flute, brought to a conclusion with his cares, went to the little crib by the paddle-box and bought tickets for the whole party.

Then Aussig came into sight, and I soon ceased to wonder whither the queer-looking crowd were going. It was to Aussig fair. Bundle after bundle was pulled so rapidly from the heap on which I reclined that I was quickly brought down to the level of the deck, and a scramble and hubbub arose easier to be imagined than described. The musicians made haste to put the leathern covers on their instruments, and along with her fiddle I saw that the leader buckled up a spare stay-bone and a few miscellaneous articles of her toilet. The women carried the harps, and the men huge knapsacks, stuffed with their wives' gear as well as their own, and with a thick-soled boot staring out from either end. Once at the landing, a few minutes sufficed to clear the deck, and no sooner had the vagabonds departed than a boy came with a broom, and all was presently made clean, as behoved in a vessel bound to Dresden.

Half an hour's stay gives you time to look at Aussig, to admire its pleasing environment, its busy boat-builders, and gondola-like pleasure-boats floating on the stream, and to commend the good quality of its beer. Among the passengers who came on board were a party of students, certain of them wearing gowns not larger than a jacket—which, as some say, betoken learning in proportion.

Away we went again, and always with fairer landscapes to greet our eyes. Past great high-prowed barges, towed slowly against the current by horses; past small barges, towed still more slowly by a dozen or twenty men. Past the Spürlingstein, and bastion-like cliffs, and hollows, beyond which you catch sight of far-away peaks. Then a village of timbered houses, the fronts showing broad lines of chequer-work and quaint gables, and every house standing apart in its own garden, among hills hung with woods to the water's edge; and rocks peering out here and there from the shadow of the trees, shutting you in all round as in a lake.

The sight of the varied features which open on you, increasing in beauty at every bend, will suggest frequent comparison. Here among the hills nature hems the Elbe in with loveliness, as if to prepare the great river for its long, dreary course from Dresden to the sea. You see not so many castles, but more variety than on the Rhine; more of untamed scenery, and less of monotonous vine-slopes; and perhaps you will incline to agree with those who hold that from Leitmeritz to Pirna the Elbe excels the far-famed stream that flows past Cologne.

Beautiful is the view of Tetschen, backed by grand wooded hills; the river, spanned by a chain-bridge, making a sudden bend; the castle looking down on the stream from a forward cliff. Though topped by a spire, the castle will inevitably remind you of a factory; and you will be constrained to look away from it to the tunnelled cliff through which the railway passes, and the noisy stream that tumbles in on the opposite side.

It had just struck one when I landed. The passport office was shut for two hours, that the functionaries might have time to dine—a praiseworthy arrangement, though trying at times to a traveller's patience. I dined at the Golden Crown, at one side of the great square, and regaled myself with a flask of Melniker—a right generous wine. The inn is the starting place for some twenty coaches and vans, and, looking round on the numerous guests as they went and came, it was easy to see you had left the Czechish for the German part of the population—oval faces for round ones.

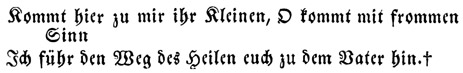

In the centre of the square stands a building, which, in appearance a pedestal for a big statue, is a little chapel in which mass is said twice a day. I spent a few minutes in looking at it, then strolled to the castle garden and the bridge, from whence I saw carts backed axle deep into the river to receive cotton bales from a barge, and women loading a boat wading out above their knees with heavy sacks on their shoulders. Then to the school—a sight that gave me real pleasure, so spacious is the building, so numerous are the scholars, so earnest the master in his work. His discourse was that of one who has found his true vocation: he was seldom cast down, and felt persuaded that it was a master's own fault if he had no joy in his scholars. After our few brief words I thought the inscription at the door yet more appropriate:

At three o'clock I sought out the passport clerk, and found him not a whit more willing to give a visa for the mountains, or a place over the border, than his fellows elsewhere. He admitted the argument that one of the pleasures of travel was an unrestricted choice or change of route, but "could not" do more; so I looked at my map, and chose Reichenberg as my next point of departure, and the official stamp and signature were forthwith applied. But the gentleman discovered an irregularity, and did not let me depart till it was rectified—that the leaves containing the visas and the passport were separate sheets. He fastened them together with a broad seal and a loop of black and yellow thread, and then wished me a pleasant journey.

The wish was realized, for the route lies through a pretty country, the most populous and industrious part of Bohemia. It is heavy uphill work soon after leaving Tetschen, but the view from the top over the valley of the Elbe repays the labour, and rivals that from the Milleschauer. A little farther, and the prospect opens in the opposite direction, across a great wave, as it seems, of cones, ridges, scars, and rounded heights, sprinkled with spires and hamlets—a cheerful scene that invites you onwards.

At every mile you see and hear more and more of the signs of industry. Men pass you wheeling barrows laden with coloured glass rods—material for beads and fragile toys, to be manufactured at home in their own little cottages, keeping up the olden practice. Now you hear the hiss and whiz of the polishing wheel; now the rattle of looms, and the croak of stocking-weavers. And at times comes a man pushing before him a great barrowful of bread—large, flat, brown loaves—on his way to supply the off hamlets which have no bakery. And now and then old women creep by, bending under a burden of firewood. Two whom I overtook told me they walked three miles twice a week to fetch a bundle of sticks from the forest; and when I asked if they ate meat or cheese, answered with a "Gott bewahr! never. Nothing but bread and potatoes."

At Markersdorf I left the highway for a cross-road, leading through a succession of hamlets, so close together that you can hardly tell where one begins and the other ends. Now the signs of labour multiply, and there is a ceaseless noise of the shuttle and polishing wheel. The little houses have a very rustic appearance, built of squared logs black with age, set off by stripes of white clay along all the joints, and a stripe of green paint around the windows. There is variety in their architecture: some imitate the Swiss style, with tall roofs and outside galleries; some exhibit dumpy gables and arched timbers along the lower story; and pretty they look in the midst of their poppy-strewn gardens and embowering orchards, watered by little brooks, which here and there set little mills a-clacking.

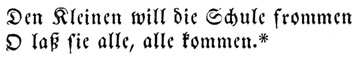

Not a hamlet without its school; and you will see with pleasure how the importance of the school is recognised. Over the door of one at Gersdorf I read:

At Meistersdorf, a furlong or two farther, on a little hill that overlooks miles of country, the school-house is one of the best buildings in the place. And here again a rhyming couplet, embodying a benevolent sentiment, crosses the lintel:

And the children really are taught. Scarcely a day passed that I did not stop boys and girls on the highway, and get them to talk about their school and what they learned. Not one did I meet above the age of eight who could not read and write, and do a little arithmetic, or recite the multiplication table, as I fully ascertained by sitting down on the bank and playing the schoolmaster—not a frowning one—myself. They answered readily, and wrote words on a scrap of paper, and seemed pleased to show off what they knew, and still more pleased at finding a kreutzer in their hand when the questions ended. In many of the schools the pupils may learn mathematics if they will, and drawing is taught in all. To this early acquaintance with the rules of art the Bohemian glass engravers are indebted for a resource that enables them to make the most of their skill and ingenuity. The school fees are from one penny to twopence a week.

A short distance beyond the school I left the village road for a rough byeway across fields, and after a walk of five hours from Tetschen came to a row of wooden cottages, or farmsteads, as they might be called, each standing apart in its own ground, flanked by sheds, and fortified by a dungheap close to the door. Were it not for overhanging trees and garden plots they would wear a shabby look.

Ulrichsthal was my destination; but here was no valley, only a slope. However, on inquiring at the last but one in the row of cottages, I found that I was really in Ulrichsthal, and at the very door I wanted.

CHAPTER XVIII

A Hospitable Reception—A Rustic Household—The Mother's Talk—Pressing Invitations—A Docile Visitor—The Family Room—Trophies of Industry—Overheating—A Walk in Ulrichsthal—A Glass Polisher and his Family—His Notions—A Glass Engraver—His Skill and Ingenuity—His Earnings—A Bohemian's Opinion on English Singing—Military Service—Beetle Pictures—Glass-making in Bohemia—An Englishman's Forget-me-Not—The Dinner—Dessert on the Hill—An Hour with the Haymakers—Magical Kreutzers—An Evening at the Wirthshaus—Singing and Poetry—A Moonlight Walk—The Lovers' Test.

I once promised a Bohemian glass engraver, who showed me specimens of his skill under the murky sky of ugly Birmingham, that when the favourable time came I would find out his native place, and have a talk with his kinsfolk. The favourable time had come in all ways, for no sooner did I make myself known to the old man who was summoned to the door, than he took my hand and said, "Be welcome to my house." Suiting action to word, he led me into a large, low room, hot as an oven, where his wife and daughters and a sweetheart sat chatting away the dusk. At first they were somewhat shy; but when I brought out a little letter from the son in England, and the eldest daughter, having lit a candle, read it aloud, the mother, overjoyed at hearing news from "our Wilhelm," sprang up, gave me a kiss, and cried, "Only think, an Englishman is come to see us!" Here was an end to the shyness; and having shaken hands with all the lasses and the sweetheart, I became as one of the family.

Of course I would stay all night; they could not think of letting me go to seek quarters at the public-house, unless, indeed, their own rustic entertainment would make me uncomfortable; and the entreaties were accompanied by preparations for supper. Who could resist such hearty hospitality? Not I; and forthwith an understanding prevailed that whatever pleased them best would please me best; excepting, that I should have leave to open one of the casements and sit close to it, for to me the temperature of the room was unbearable. Besides the heat from the stove, there was an odour of kine from the cowstall, which forms one half of the house, separated from the living room only by a passage.

We had merry talk while I ate my supper of eggs, coffee, and bread and butter. "Our Wilhelm" was, however, the mother's favourite topic, and she returned to it again and again. She must tell me, too, of her other sons, one in America, another at Pesth; and how that one night they were all awoke by a loud knocking at the door, and a voice begging for a night's lodging. How that the stranger would not go away, but continued to knock and beseech, until all at once the mother recognised a tone, and cried, "Father, father, open the door! That's our David's voice. Our David, come home to see us, all the way from Hungary!" And then the joyful meeting that followed! Her eyes glistened with tears as she told me this.

There were two beds in a little slip of a chamber opening from the principal room, of which the one nearest the window was given up to me, as I again had to stipulate for an open casement; and the more so, as notwithstanding the heat, I was expected to bury myself between two feather-beds, as the custom of the country is; the other was occupied by the old man. As for mother and daughters, they retreated to some place overhead, which must have been very like a loft.

Had I slept well? was the question next morning; and this being answered in the affirmative, the family resolved by acclamation that I should stay with them a fortnight at least, nor would they at first believe that I could only spare them a single day. Could not an Englishman do anything? What mattered it if I returned to London a week sooner or later? The theatre at Steinschönau would be opened on Sunday, and it would be such a nice walk to go and see the play. Why should I be in a hurry to reach the mountains? Would it not be the same if I went to the top of all the hills around Ulrichsthal?

So said the daughters, with much more of the like purport, and to resist persuasions backed by bright eyes, good looks, and blithesome voices, was a hard trial for my philosophy. However, I kept my resolution even when the mother rounded up with, "Only a day! that's not long enough to taste all my cookery." The good soul had risen early to make fresh Semmel for breakfast.

To pacify them, I promised to eat as much as ever I could, and to let them do whatever they liked with me during the day. Thereupon two of the damsels put on their broad-brimmed straw hats, shouldered their rakes, and betook themselves to the hay-field; the youngest, a lassie of fifteen, apprenticed to a glass engraver, said, "Leb' wohl," and went away to her work; the old man, privileged to be idle through age and infirmity, crept forth to find a sunshiny bit of grass on which to have a snooze; the mother began to bustle with pot and pan about the stove; and the eldest daughter, having put on her hat and a pink scarf, claimed the right to show me all that was worth seeing in Ulrichsthal.

We began with the room itself. Its furniture was simple enough: wooden walls and ceiling; an uncomfortable wooden seat fixed to the wall along two sides; a table and a few wooden chairs; and the old man's polishing-bench, a fixture in one corner. The treadle and crank were still in place, but motionless; half a dozen wheels and sundry tools hung on the wall, memorials of the veteran's forty years of industry, and the bench did duty as dresser and bookshelf. Among the books were Schiller's Werken, in sixteen volumes, belonging to "our Wilhelm." With that simple machinery, hoarsely whirring day after day all through the prime of his manhood, had he gained wherewith to buy his two plots of land, and the comfort of repose in declining age. Here, in this overheated room, at once workshop, kitchen, and parlour, had been reared those four comely daughters, and the tall son whom I had met in England; all strong and hearty, in spite of high temperature and certain noxious influences arising out of a want of proper decency in the household economy. "We are used to it," was the answer, when I expressed my surprise that they could bear to live familiar with things offensive, and yet fearful of a passing breath from spring and summer. But this want of perception is not confined to Ulrichsthal; you cannot help noticing it in many, if not in most, Bohemian villages, and on the Silesian side of the mountains.

But the damsel is impatient. We set off towards a row of houses on a higher part of the slope. Each has its long and narrow piece of land, an orchard immediately behind the house; then patches of wheat, barley, poppies, beetroot, grass, and potatoes, cultivated, with few exceptions, by the several families. But labourers can be hired when wanted, who are willing to work for one or two florins a week.