полная версия

полная версияThe Story of Our Flag

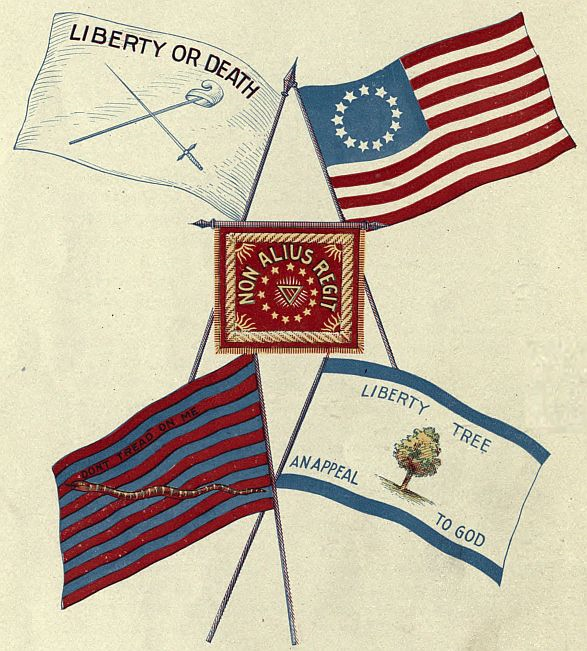

GROUP OF COLONIAL FLAGS, NO. 1

The two upper flags of this group represent those used at Bunker Hill July 18, 1775, and bore these inscriptions: On one side, “An Appeal to Heaven,” and on the other, “Qui Transtulit Sustinet”—He who transported will sustain.

These were beautiful flags, and research shows that both colors were used.

Trumbull gives the red in his celebrated painting in the capitol at Washington, and other authentic accounts show that the blue flag was carried also—the color being the only difference in the two.

THE PINE TREE FLAG

The pine tree flag which was a favorite with the officers of the American privateers, had a white field with a green pine tree in the middle and bore the motto, “An appeal to heaven.”

This flag was officially endorsed by the Massachusetts council, which in April, 1776, passed a series of resolutions providing for the regulation of the sea service, among which was the following:

Resolved, That the uniform of the officers be green and white, and that they furnish themselves accordingly, and that the colors be a white flag with a green pine tree and the inscription, “An appeal to heaven.”—Harper’s Round Table.

COPYRIGHT 1898, BY ADDIE G. WEAVER.

The striped Continental flag opposite the pine tree flag was of red and white stripes without a field.

THE RATTLESNAKE FLAG

The device of a rattlesnake was popular among the colonists, and its origin as an American emblem is a curious feature in our national history.

It has been stated, that its use grew out of a humorous suggestion made by a writer in Franklin’s paper—the Pennsylvania Gazette—that, in return for the wrongs which England was forcing upon the colonists, a cargo of rattlesnakes should be sent to the mother country and “distributed in St. James’ Park, Spring Garden and other places of pleasure.”

Colonel Gadsden, one of the marine committee, presented to Congress, on the 8th of February, 1776, “an elegant standard, such as is to be used by the commander-in-chief of the American navy; being a yellow flag with a representation of a rattlesnake coiled for attack.”

WASHINGTON LIFE GUARD FLAG

There is probably no more interesting revolutionary flag than this. The Washington Life Guard was organized in 1776, soon after the siege of Boston, while the American army was encamped near New York.

It was said to have been in the museum at Alexandria, Va., which was burned soon after the war of the rebellion, and nearly everything lost. It was of white silk with the design painted on it.

The uniform of the guard was as follows: blue coat with white facings, white waistcoat and breeches, with blue half gaiters, a cocked hat and white plume.

THE GRAND UNION FLAG

These were the colors selected by Franklin, Harrison and Lynch, and unfurled by Washington under the Charter Oak, January 2, 1776, and hereafter described.

The flag of the Richmond Rifles follows with the one used at Moultrie.

The latter was of blue with white crescent in the dexter corner and was used by Colonel Moultrie, September 13, 1775, when he received orders from the Council of Safety for taking Fort Johnson on James Island, South Carolina.

In the early years of the Revolution, a number of emblems were in use which became famous. The standard on the southeast bastion of Fort Sullivan (or Moultrie, as it was afterward named), on June 28, 1776, by Colonel Moultrie, was a blue flag with a white crescent in the upper left hand corner, and the word “Liberty” in white letters emblazoned upon it.

This was the flag that fell outside the fort and was secured by Sergeant Jasper, who leaped the parapet, walked the whole length of the fort, seized the flag, fastened it to a sponge staff and in sight of the whole British fleet and in the midst of a perfect hail of bullets planted it firmly upon the bastion. The next day Governor Rutledge visited the fort and rewarded him by giving him his sword.

Then comes the flag of White Plains, October 28, 1776, with little historical importance.

The flag made by Betsy Ross, under the direction of General Washington, Robert Morris, and Colonel George Ross, consisted of thirteen bars, alternate red and white, with a circle of thirteen stars in the field of blue.

COPYRIGHT 1898, BY ADDIE G. WEAVER.

COUNT PULASKI’S FLAG

The Moravian sisters of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, gave to Count Pulaski’s corps, which he had previously organized at Baltimore and which was called “Pulaski’s Legion,” a beautiful crimson silk banner, embroidered in yellow silk and sent it with their blessing. Pulaski was at this time suffering from a wound, and was on a visit to Lafayette, whose headquarters were at Bethlehem. Count Pulaski was a Polish patriot, born March 4, 1747. After having bravely fought for Poland with his father and brothers until the Polish cause became hopeless, he came to America, arriving in Philadelphia in 1777. He entered the army as a volunteer, but performing such brave service at Brandywine, he was promoted to the command of cavalry with rank of brigadier-general. In 1778 Congress gave him leave to raise a body of men under his own command. Longfellow has most beautifully described the presentation of the flag in verse. Pulaski bore this flag to victory through many battles until he fell mortally wounded at Savannah, October 14, 1779. The banner was saved by his first lieutenant, who received fourteen wounds, and delivered it to Captain Bentalon, who on retiring from the army, took it home to Baltimore. It was carried in the procession which welcomed Lafayette in 1824, and was then deposited in the Peale Museum. In 1844 Mr. Edmund Peale presented it to the Historical Society of Maryland, where it is now preserved in a glass case. These are interesting historical facts.

Flag of red and blue bars with serpent stretched across and words, “Don’t Tread on Me.”

Another flag of white, with blue bands top and bottom and a pine tree in center, with the inscriptions: Liberty Tree and An Appeal to Heaven.

THE “DON’T TREAD ON ME” FLAG

Another use of the rattlesnake was upon a ground of thirteen horizontal bars alternate red and white, the snake extending diagonally across the stripes, and the lower white stripes bearing the motto—“Don’t Tread on Me.” The snake was always represented as having thirteen rattles, and the number thirteen seems constantly to have been kept in mind. Thus, thirteen vessels are ordered to be built; thirteen stripes are placed on the flag; in one design thirteen arrows are grasped in a mailed hand; and in a later one thirteen arrows are in the talons of an eagle.

ANOTHER “DON’T TREAD ON ME” FLAG

One of the favorite flags also was of white with a pine tree in the center. The words at the top were “An Appeal to God,” and underneath the snake were the words, “Don’t Tread on Me.” Several of the companies of minute men adopted a similar flag, giving the name of their company with the motto “Liberty or Death.” This flag is familiar to the public as the annual celebrations bring out descriptions of it in the press.

THE PRESIDENT’S FLAG

Within the last few years special flags have been designed for the President, the Secretary of the Navy and Secretary of War. The President’s flag is a very beautiful blue banner, in the center of which is a spread eagle bearing the United States shield on its breast, with the thirteen stars in a half circle overhead. It is flown at the main mast-head of naval vessels while the President remains on board, and on being hoisted it is the signal for the firing of the President’s salute.

COLONIAL AND PATRIOTIC MUSIC

The colonial music was mostly borrowed and adapted to the occasion. The Pilgrims had more important duties to perform and in those years of stirring events no one was in a mood to write music.

The first song to be used was that old and familiar one, “Yankee Doodle.” It made a powerful rallying cry in calling to arms against England. It is so old that it is impossible to decide just where the term came from.

It has been traced back to Greece—“Iankhe Doule,” meaning “Rejoice, O Slave,” and to the Chinese—“Yong Kee,” meaning “Flag of the Ocean.” It is said the Persians called Americans “Yanki Doon’iah,” “Inhabitants of the New World.” The Indians too, come in for their share of the credit of originating the term, as the Cherokee word “Eankke,” which means “coward” and “slave,” was often bestowed upon the inhabitants of New England.

At the time of the uprising against Charles the First, Oliver Cromwell rode into Oxford, on an insignificant little horse, wearing a single plume in a knot called a “macaroni.” The song was sung derisively by the cavaliers at that time. The tune is said to have come from Spain or France, there being several versions of the words.

It came into play when our ancestors flocked into Ticonderoga in answer to the call of Abercrombie. At that early day no one refused, but all answered the call and came equipped as best they could, but hardly any two alike, and to the trained English regulars must have presented a ridiculous appearance. Dr. Shamburg changed the words of the old satire to fit the new occasion. But in less than a year it was turned by the Yankees against the English in the form of a rallying cry and possessed new meaning.

History had emphasized it, and with the accompaniment of the shrill pipe and half worn drum calling the simple cottagers together, it must have aroused all their noble and sturdy patriotism.

Who that has viewed that stirring picture in the Corcoran Art Gallery at Washington, “Yankee Doodle,” could fail to catch the inspiration of the scene. The old man with his thin grey locks, but head erect and face glowing with enthusiasm as he keeps time to the old tune, followed by the small boy with his drum. One scarcely knows whether humor or pathos predominates: but certain we are that all alike stepped to its chords; it found an answering echo in each heart and led them on to glory.

YANKEE DOODLE

Father and I went down to camp.Along with Captain Goodwin,And there we saw the men and boysAs thick as hasty pudding.CHORUSYankee Doodle, keep it up.Yankee doodle dandy;Mind the music and the step.And with the girls be handy.And there was Captain Washington,Upon a slapping stallion.A giving orders to his men.I guess there was a million.—Cho.And then the feathers on his hat.They looked so tarnal finey,I wanted peskily to getTo give to my Jemima.—Cho.And there they had a swamping gun.As big as a log of maple,On a duced little cart,A load for father’s cattle.—Cho.And every time they fired it offIt took a horn of powder;It made a noise like father’s gun,Only a nation louder.—Cho.I went as near to it myselfAs Jacob’s underpinin’,And father went as near again,I th’t the duce was in him.—Cho.It scared me so, I ran the streets,Nor stopped as I remember,Till I got home and safely lockedIn granny’s little chamber.—Cho.And there I see a little keg.Its heads were made of leather;They knocked upon it with little sticksTo call the folks together.—Cho.And then they’d fife away like funAnd play on corn-stalk fiddles;And some had ribbons red as bloodAll bound around their middles.—Cho.The troopers, too, would gallop up,And fire right in our faces;It scared me almost to deathTo see them run such races.—Cho.Uncle Sam came there to changeSome pancakes and some onions,For ’lasses cake to carry homeTo give his wife and young ones.—Cho.But I can’t tell you half I see,They keep up such a smother:So I took off my hat, made a bow,And scampered off to mother.—Cho.AMERICA

Rev. Samuel Francis Smith was born in Boston October 21, 1808, and graduated in the class of ’29 from Harvard University. He enjoyed the honor of having for his classmate Oliver Wendell Holmes, in whose beautiful poem, entitled “The Boys,” the name of the author of “America” is affectionately mentioned.

And there’s a nice youngster of excellent pith;Fate tried to conceal him by naming him Smith.But he shouted a song for the brave and the free,Just read on his medal—“My Country of Thee”!“America” was written in 1832, the tune being the old one of “God Save the Queen,” and first rendered on the 4th of July of the same year by the children of Park St. Church, Boston.

AMERICAMy country, ’tis of thee,Sweet land of liberty,Of thee I sing!Land where my fathers died,Land of the pilgrims’ pride,From every mountain sideLet freedom ring.My native country, thee—Land of the noble free,Thy name I love.I love thy rocks and rills,Thy woods and templed hills.My heart with rapture thrillsLike that above.Let music swell the breezeAnd ring from all the treesSweet Freedom’s song!Let mortal tongues awake,Let all that breathe partake,Let rocks their silence break,The sound prolong.Our fathers’ God, to thee,Author of Liberty!To Thee we sing:Long may our land be brightWith freedom’s holy light,Protect us by Thy might,Great God, our king!Peace follows where it finds the Old Thirteen, the nucleus around which the other stars have gathered in their glory.

—Letitia Green Stevenson, Honorary Vice President General National Society, Daughters of the American Revolution.

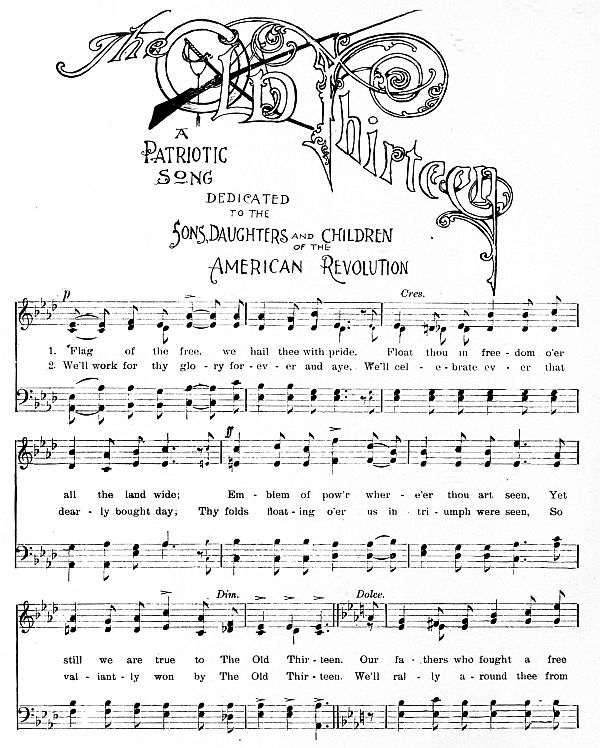

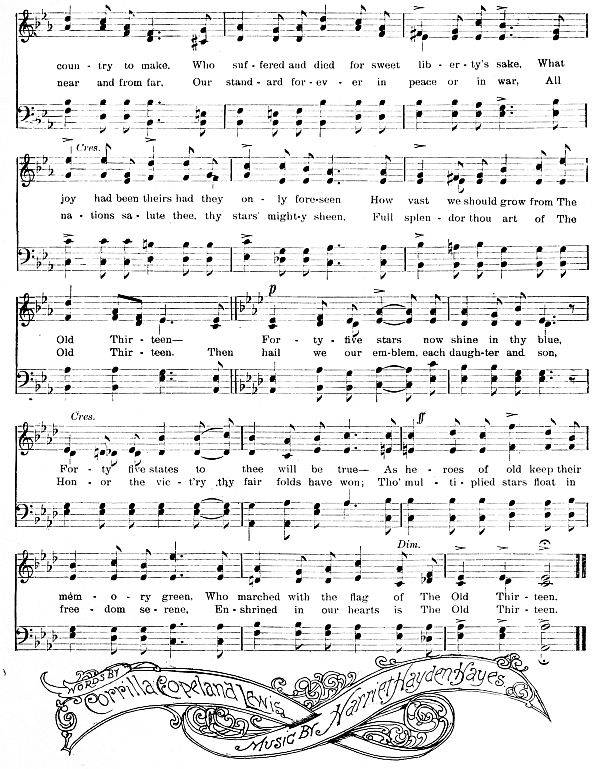

The Old Thirteen

A Patriotic Song DEDICATED TO THE Sons, Daughters and CHILDREN OF THE American Revolution1. Flag of the free, we hail thee with pride.Float thou in freedom o’er all the land wide;Emblem of pow’r where’er thou art seen. Yetstill we are true to The Old Thirteen.Our fathers who fought a free country to make.Who suffered and died for sweet liberty’s sake.What joy had been theirs had they only foreseenHow vast we should grow from The Old Thirteen—Forty-five stars now shine in thy blue,Forty-five states to thee will be true—As heroes of old keep their memory green.Who marched with the flag of The Old Thirteen.2. We’ll work for thy glory forever and aye.We’ll celebrate ever that dearly bought day;Thy folds floating o’er us in triumph were seen,So valiantly won by The Old Thirteen.We’ll rally around thee from near and from far,Our standard forever in peace or in war,All nations salute thee, thy stars’ mighty sheen,Full splendor thou art of The Old Thirteen.Then hail we our emblem, each daughter and son,Honor the vict’ry thy fair folds have won;Tho’ multiplied stars float in freedom serene,Enshrined in our hearts is The Old Thirteen.Words ByCorrilla Copeland LewisMusic By Harriet Hayden HayesSTARS ON THE FLAG

The Home Magazine contains the following beautiful suggestion regarding the placing of the stars on the flag:

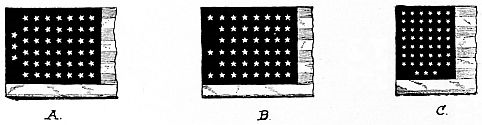

Number 1 is the field of our first stars and stripes made by Betsy Ross.

Number 2 represents that field of flag of 1814 which inspired the “Star Spangled Banner.”

Number 3 the field of 1818 designed by Capt. S. C. Reid.

Number 4, field of our present flag.

Although there is no law saying who shall arrange the stars on our flag, or how they shall be arranged, it is customary for the changes to be made in the war department when new states have been admitted to the Union.

The incongruous variations in figures A, B, C, which are reproductions of unions taken from new flags, made by different manufacturers, would not exist if there was a law fixing the arrangement of the stars.

It is believed by many that the stars on our flag should be arranged into a permanent and symmetrical form, fixed by law, instead of the present changeable and uncertain form, which is subject in a great measure, to the caprice or convenience of the flag maker. It is not generally known that among the many flags in use in our country to-day, there is an utter lack of uniformity in the arrangement of the stars.

In the selection of a form, three different things should be considered—its historical significance, symmetry, and adaptability. The stars should be so arranged that it will not be necessary to make any noticeable change when new ones are added. The stars should always remain equal in size, representing the equality of the states.

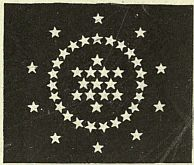

In the form which is submitted, No. 8, with the group of thirteen stars in the center, representing the thirteen original states, they are arranged in exactly the same form as they appear on the great seal of the United States. The circle containing twenty-three stars, represents the states which were admitted to the Union up to the close of the civil war. These two features are symbolic of the two great events in the nation’s history—the one which brought our flag into existence, and the other which made its life permanent by welding the sisterhood of states into a perfect and indestructible union. The circle is also symbolic of unity, peace, and preservation.

The outside circle of nine stars, represents the states which have been added to the Union since the civil war. New stars can be added to this circle without changing the symmetry of the arrangement, as will be seen by reference to the illustration. As this circle will always remain an open one, there will always be room for one more star, and it is thus significant of progression.

One great advantage in this form is, that it is suggestive of a constellation, and thus carries out, as far as practicable, the idea of the framers of the resolution of 1777 in establishing the flag.

John F. Earhart is the author of the above description of the different forms of flags.

THE LIBERTY CAP

The historians who have searched the archives of ancient and medieval times tell us that this has been a symbol of liberty since the Phrygians made the conquest of the eastern part of Asia Minor.

After the conquest they stamped it on their coins, and to distinguish themselves from the primitive peoples they used the liberty cap as a head dress. The Romans used a small red cap called a “pileus,” which they placed on the head of a slave in making him free, and when Caesar was murdered a Phrygian cap was carried through the streets of Rome proclaiming the liberty of the people. The liberty cap of the English is blue with a white border.

It remained for the United States to adopt the British cap, adding to it the crescent of thirteen stars. Generals Lee and Schuyler, with the Philadelphia Light Horse troop, adopted it in 1775. This is the famous troop that escorted Washington to New York.

It is most familiar to us as seen on our coins, on which it was first used after the Revolution as a symbol of freedom.

Edward Everett Hale, in one of his impressive orations, says: “The starry banner speaks for itself; its mute eloquence needs no aid to interpret its significance. Fidelity to the Union blazes from its stars; allegiance to the government beneath which we live is wrapped in its folds.”

The Stars and Stripes was officially first unfolded over Ft. Schuyler, a military port in New York state, now the city of Rome, Oneida county. It was first saluted on the sea by a foreign power, when floating from the masthead of the Ranger, Capt. Paul Jones commanding, at Quiberon Bay, France, February 14, 1778. The salute was given by Admiral La Motte, representing the French government.

The first vessel over which the Union flag floated was the ship Ranger, built at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, whose gallant commander was the famous Paul Jones.

Its first trip around the world was on the ship Columbia, which left Boston September 30, 1787, commanded by Captains Kendrick and Gray. It was three years then in circling the globe. To-day it waves in every clime, on every sea.

It is pleasing to note how Franklin, when minister to France, secured the ship Doria from the French and gave to Paul Jones the command, who immediately renamed the old ship “Bon homme Richard,” in honor of Franklin.

ORIGIN OF “OLD GLORY.”

The term Old Glory is said to have been originated by an old sailor—Stephen Driver.

While upon the seas he performed an act of bravery for which he was rewarded by the gift of an American flag, whereupon he pledged its givers to always defend it faithfully.

At the outbreak of the civil war he was living in Nashville, Tenn.

In order to keep the flag safely he concealed it in a bed-quilt under which he slept. To the enemies of the Union he declared that Old Glory would yet float from the staff of the Tennessee state house, and sure enough when Nashville fell into the hands of Gen. Buell he secured the flag from its hiding place and hoisted it to a more fitting position on the state house—thus his nick-name for it became popular.

JOHN JAY AT MOUNT KISCO, JULY 4, 1861

He said, “Swear anew and teach the oath to our children, that with God’s help the American Republic shall stand unmoved though all the powers of piracy and European jealousy should combine to overthrow it. That we shall have in the future as we have had in the past, one country, one constitution, one destiny; and that when we shall have passed from earth, and the acts of to-day shall be matters of history, and the dark power which sought our overthrow shall have been overthrown, our sons may gather strength from our example in every contest with despotism that time may have in store to try their virtue, and that they may rally under the Stars and Stripes with our old time war cry,

“‘Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable.’”

UNCLE SAM

This term originated at the time of our war with England in 1812. Provisions were purchased at Troy, N. Y., and the agent was Elbert Anderson, the work being superintended by Ebenezer and Samuel Wilson, the packages being marked E. A. U. S. Samuel Wilson was known all over as Uncle Sam and he was often joked about his amount of provisions, then the newspapers took it up and the term Uncle Sam came into general use and is typical of our increasing national prosperity. Quite recently a portrait of an actual personage whose features are identical with those made familiar by caricatures of Uncle Sam, was found in possession of a family near Toledo, Ohio. The portrait was painted about 1818, but nothing is known of the shrewd, kindly old man represented. His face was undoubtedly the origin of the accepted caricature.

BROTHER JONATHAN

Jonathan Trumbull, governor of Connecticut, was a warm friend of General Washington, who had great confidence in his judgment.

When in need of ammunition and the question arose as to where they could get the necessary means for defense Washington said: “We will consult Brother Jonathan.”

After that whenever they needed help the expression became a common one and naturally came to mean the United States Government.

THE AMERICAN EAGLE

Our bald headed eagle, so called because the feathers on the top of the head are white, was named the Washington eagle by Audubon. Like Washington it was brave and fearless, and as his name and greatness is known the world over, so the greatest of birds can soar to the heights beyond all others.

In 1785 it became the emblem of the United States.

It is used on the tips of flag staffs, on coins, on the United States seals, and on the shield of liberty.

BANNERS AND STANDARDS

It is not generally known that the tassels which are pendent customarily from the upper part of banners and standards, and the fringe which surrounds them are relics of the practice of observing sacred emblems. They originated in pagan devices and the garments of priests and were consecrated to specific forms of worship.