полная версия

полная версияA Little Preserving Book for a Little Girl

When cold, Adelaide wiped each tumbler, poured melted paraffin over the top of marmalade, shook gently from side to side to exclude all air, pasted on the labels, and stored away in the preserve closet.

Apple marmalade came next, and mother thought that that was sufficient for the present.

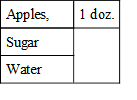

Apple Marmalade

These were nice tart apples of fine flavor. Adelaide washed them well, cut into quarters (removing stem and blossoms only), put in saucepan, and added enough water to almost, though not quite, cover the apples. These she cooked slowly until very soft, then pressed them through a strainer. She next measured the fruit, returned it to the saucepan, and to each cup of fruit added three-fourths of a cup of sugar. Returning the saucepan to the fire, Adelaide let it boil gently for three-quarters of an hour, stirring every little while.

The sterilized tumblers were ready, and into these Adelaide poured the marmalade; when cool she wiped the tops and outsides clean, poured melted paraffin over the marmalade, shook the tumblers from side to side gently to exclude all air, pasted on the labels, and stored away in the preserve closet.

CHAPTER II

JAMS

Of course Adelaide did not make her jams, jellies, etc., in the order given, but according to the season, and she welcomed each fruit in its turn. Adelaide was especially fond of jams; they did make the most delicious sandwiches when she came home hungry from school or went on a picnic, but the climax of enjoyment was reached when mother made rolly-polly jam puddings in the winter.

Strawberries were usually first on the market, and so "Strawberry Jam" was the first attempt in the jam making line.

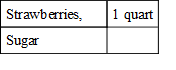

Strawberry Jam

Mother told Adelaide to empty the strawberries into the colander and place in a pan of cold water, then to dip the colander up and down so as to thoroughly cleanse the berries; next to change the water two or three times until it was clear, then lift out the colander and drain. Mother also said that you should never wash berries after they were hulled, because if you did you lost part of the juice.

After Adelaide felt sure they were clean, and after mother had carefully inspected them, she commenced to hull the berries, using the strawberry huller, then she weighed the berries and measured out three-fourths their weight in sugar.

With a wooden potato masher Adelaide mashed the berries in the saucepan and poured over the sugar; this mixture she let stand a few minutes before putting the saucepan on the stove and letting it come slowly to the boiling point. When the fruit had cooked slowly for forty-five minutes, Adelaide stirring frequently, meanwhile, with the wooden spoon, it was ready for her to pour into sterilized tumblers, which she had previously prepared. The tops and outsides of the tumblers she wiped with a clean cloth as soon as the jam had cooled, then poured melted paraffin over the jam, and shook gently from side to side to make it air tight.

Adelaide was always glad when it came time to paste on the neat little labels and put the tumblers away in the preserve closet; she was very much surprised, too, to see how quickly her bench was becoming filled.

In the beginning, mother had told her that sometimes it would seem as though she spent all of her time preserving, for the fruits and vegetables followed fast upon one another, but Adelaide replied she was sure she would not mind, she was so eager to learn.

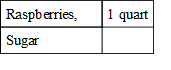

Raspberry Jam

Adelaide picked over the raspberries before washing them, and mother told her to keep a sharp look-out for little worms that sometimes curled themselves up in the center, and you may be sure Adelaide's keen eyes never missed one if there were any. Next she put them in the colander, and then dipped the colander up and down in a pan of clear cold water several times. When all possible dirt had been washed away, Adelaide stood the colander to drain, after which she poured the berries into the saucepan and weighed them.

Adelaide found it a great convenience to know the weight of each saucepan she used, and she kept a little card showing just how much each one weighed, then when they were weighed with the fruit, all she needed to do was to subtract the weight from the total of the saucepan to find out how much the fruit weighed.

To each pound of raspberries Adelaide measured three-fourths of a pound of sugar, then she mashed the berries, added the sugar, and let the mixture stand a short time before putting it on the stove to cook.

When the fruit had become heated to the boiling point, Adelaide let it cook slowly for forty-five minutes, not forgetting to stir with the wooden spoon to keep from burning; meanwhile, she had sterilized the tumblers and they were ready when the jam had finished cooking. Adelaide poured the jam into the tumblers at once, and as soon as it had cooled she wiped the tops and outsides carefully, poured melted paraffin over the jam, shook it gently from side to side to make it secure from the air, pasted on the labels, and stored them away in the preserve closet.

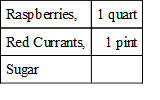

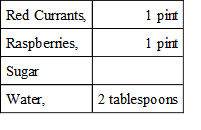

Raspberry and Red Currant Jam

First, Adelaide picked over the raspberries very carefully and placed them in the colander, then she removed the stems from the currants and added them to the raspberries. These she then dipped in clear cold water several times and set aside to drain. Next she weighed the fruit, and to each pound she added a pound of sugar.

She mashed the fruit well with the wooden masher in the saucepan and poured over the sugar. After a few minutes the juice began to run and she put the saucepan on the stove, letting the jam heat slowly through. When it boiled, Adelaide stirred it frequently and let it cook forty-five minutes. It was then ready to pour into the sterilized tumblers. When cold, she wiped the top and outside of each tumbler, poured melted paraffin over the jam, shook it gently from side to side, thus excluding all air, pasted on the labels and put away in the preserve closet.

This combination of raspberries and red currants was a great favorite with everybody.

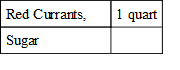

Red Currant Jam

The red currants Adelaide removed from their stems and put in the colander to be thoroughly washed. This was done by dipping the colander up and down in a pan of clear cold water. If they were very dusty, she changed the water several times.

After draining the currants sufficiently, she weighed them and put them into the saucepan. To each pound of fruit Adelaide added one pound of sugar. With the wooden masher she mashed the currants and stirred them well with the sugar.

Putting the saucepan on the stove, she let the fruit come slowly to the boiling point, stirring with the wooden spoon frequently to prevent it from burning. It boiled gently for forty-five minutes, then Adelaide poured it into sterilized tumblers at once and stood them away to cool. When they were cold she wiped the top and outside of each tumbler, poured melted paraffin over the jam, shaking it gently from side to side to keep out any air, pasted on the labels and stored away in the preserve closet.

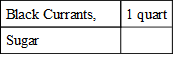

Black Currant Jam

Adelaide found that when she used red currants, the picking off of the stems consumed a lot of time, so she was glad to find the black currants come already stemmed.

Putting the black currants in the colander, she proceeded to wash them thoroughly by dipping the colander up and down in a pan of clear cold water several times. If they were very dusty she changed the water two or three times until it was clear. After weighing the currants she poured them into a saucepan, mashed them with the wooden masher, added an equal weight of sugar, mixed well with the wooden spoon, let stand until the juice ran, then put the saucepan on the stove and let the mixture come slowly to the boiling point, stirring occasionally. While this was boiling gently for forty-five minutes, Adelaide sterilized the tumblers, not forgetting, however, to stir the jam frequently.

When it was cooked she poured the jam at once into the tumblers and let it cool; as soon as it was cold, Adelaide wiped each tumbler thoroughly, inside the top and on the outside, poured melted paraffin over the jam, which she shook gently from side to side to keep out all air, then pasted on the labels and stored away in the preserve closet.

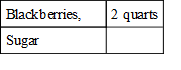

Blackberry Jam

Mother explained to Adelaide that the flavor of the blackberry was delicious, but you did not enjoy it so much if the seeds were allowed to remain, so that jam was prepared a little differently.

After picking the blackberries over carefully, Adelaide put them in the colander, then dipped it up and down in a pan of cold water and set aside to drain. Afterwards, she put the fruit in the saucepan and with the wooden masher mashed it well. Then she stood the saucepan over the fire and let the fruit come gradually to the boiling point. While she let the fruit boil gently for twenty minutes, Adelaide stirred frequently, using the long wooden spoon.

Moving the saucepan from the fire, Adelaide then rubbed the fruit through a fine sieve (mother said if the sieve let the seeds pass through to use a cheesecloth bag) and measured. To each cup of juice, which she returned to the saucepan, she added three-fourths of a cup of sugar, and putting the jam back over the fire, let it heat slowly, stirring often. This took three-quarters of an hour of gentle boiling before it was done.

Adelaide poured at once into the sterilized tumblers, which were waiting to be filled, and set aside to cool. When cold, she wiped the tops and outsides carefully with a damp cloth, poured melted paraffin over the jam, shaking it gently from side to side, thus keeping out all air, pasted on the labels, and stored the jars away in the preserve closet.

Gooseberry Jam

"The jams with a nice tart flavor," Adelaide said, "are the ones Daddy likes best." He was especially fond of gooseberry jam and for that reason Adelaide decided to surprise him.

The gooseberries Adelaide put in the colander and dipped up and down in a pan of clear cold water until thoroughly clean, then she drained them. With the strawberry huller she pulled off the tops, though she could have used the little sharp knife; next she weighed the gooseberries and put them in the saucepan to be mashed with the wooden masher.

To each pound of fruit she added a pound of sugar, placed the saucepan over the fire and let the fruit come slowly to the boiling point. This needed to be stirred with the wooden spoon occasionally, but after it had reached the boiling point Adelaide stirred it very frequently to prevent burning. It took three-quarters of an hour to cook, and then Adelaide filled the sterilized tumblers with the jam and set it aside to cool. When the jam was cold she wiped each tumbler around the top and on the outside with a clean damp cloth, poured melted paraffin over the jam, pasted on the labels and stored away in the preserve closet.

Of course Daddy was very much pleased with this jam.

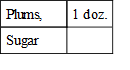

Large Blue Plum Jam

The large blue plums, Adelaide's mother said, made delicious jam. Adelaide washed and wiped each plum carefully, then slit each one with a silver knife and took out the stone. After weighing them and putting the plums in the saucepan she added three-fourths of a pound of sugar to each pound of fruit, letting them stand until the juice ran. Placing the saucepan over the fire, she stirred the fruit occasionally until it reached the boiling point, after which she let it boil slowly, for forty-five minutes, and continued to stir very frequently to prevent the jam from burning or sticking to the bottom. In the meantime, Adelaide had the tumblers sterilized and waiting, and as soon as the jam had finished cooking she poured it at once into the tumblers. When the jam was cold she wiped the top and outside of each tumbler with a clean damp cloth and poured melted paraffin over the jam, shaking it gently from side to side to exclude all air. Next came the labels, and then the tumblers of jam were stored away in the preserve closet.

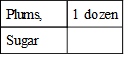

Green-Gage Plum Jam

The green-gage plums, Adelaide found, came later in the season, but they were worth waiting for. These she cut open with a silver knife, after having washed and wiped them carefully, and removed the stones. Weighing the plums, she put them in the saucepan, and to each pound of fruit she added three-quarters of a pound of sugar. When the juice began to run she placed the saucepan over the fire, and let the jam come slowly to the boiling point, stirring it every little while; continuing to cook the jam for forty-five minutes, Adelaide stirred frequently to prevent its sticking to the bottom and becoming burned. As soon as the jam had cooked sufficiently she poured it into the sterilized tumblers which were ready, and when the jam was cold, Adelaide wiped the tops and outsides of the tumblers with a clean damp cloth, poured melted paraffin over the top, and shook gently from side to side to exclude all air. The labels were next pasted on, and the jam was then stored away in the preserve closet.

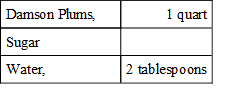

Damson Plum Jam

Compared to the large blue plums and the green-gage plums Adelaide found the damson plums quite small, and mother told her they would have to be cooked first before she could remove the stones easily. So Adelaide washed the Damson plums carefully, and with a silver knife slit each one before putting them into the saucepan. This was to let the juice run. But, first, Adelaide measured two tablespoons of cold water into the saucepan, then poured in the plums. Of course she had weighed the plums as usual, and also an equal amount of sugar, but the sugar she placed in a bowl and placed on one side until ready to use. The saucepan was then placed over the fire and the plums were cooked slowly until tender, when they were removed, and with two silver forks Adelaide easily picked out the stones. Adding the sugar, she returned the saucepan to the fire, and while it was coming to the boiling point she stirred constantly with a wooden spoon, so that the sugar would not stick to the bottom and burn. Still continuing to stir, she let the jam cook slowly for forty-five minutes.

The tumblers had been sterilized and the jam was poured into them at once. After the jam was cold Adelaide wiped the top and outside of each tumbler with a clean damp cloth, then poured melted paraffin over the top, and shook gently from side to side to exclude the air, pasted on the labels and stored the jars away in the preserve closet.

There were many other kinds of plums, but these were the ones that had the best flavors, mother said, and quite enough for Adelaide to experiment with for the present.

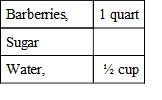

Barberry Jam

Barberries make a very tasty jam. Adelaide put them in the colander, which she dipped up and down in a pan of clean cold water until free from all dust, then carefully picked them over. Into the saucepan she poured one-half a cup of cold water, then added the barberries. Placing the saucepan over the fire, she let the barberries become just warm, then Adelaide pressed the fruit through a wire strainer and measured. To each cup of fruit she added a cup of sugar, which she returned to the saucepan, placed over the fire, let it heat gradually to the boiling point, then cooked twenty minutes, stirring constantly with the wooden spoon. The sterilized tumblers were waiting, and into these Adelaide poured the jam. When the jam was cold she wiped the tops and outsides with a clean damp cloth, poured melted paraffin over the jam, shaking it gently from side to side to exclude all air, then pasted on the labels and stored jam away in the preserve closet.

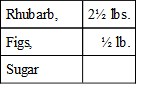

Rhubarb and Fig Jam

An English friend gave this recipe to Adelaide, and it proved to be very "tasty."

The friend said to choose the pretty pink rhubarb, then wash and wipe it thoroughly, and cut with a sharp knife into one-inch pieces. The figs were looked over carefully and Adelaide cut out the hard little part near the stem, then she put them through the meat chopper and added them to the rhubarb. When she had weighed the prepared fruit and put it into the saucepan she poured over it three-fourths its weight of sugar, and let the mixture stand until the juice ran. Placing the saucepan over the fire, she let the fruit come slowly to the boiling point, stirring with a wooden spoon occasionally. After it had boiled Adelaide stirred it frequently and cooked gently three-quarters of an hour. It was then ready to pour into the sterilized tumblers, which Adelaide never failed to have on hand, and stood away to cool.

When it was cool she wiped the top and outside of each tumbler with a clean damp cloth, poured melted paraffin over the jam, shaking it gently from side to side to exclude all air, then pasted on the labels and stored the jam away in the preserve closet.

CHAPTER III

JELLIES

When mother gave Adelaide her first lesson in jelly making, Adelaide had visions. Jelly rolls, thin bread and butter sandwiches with jelly in between, soft boiled custards served in individual glasses with a spoonful of jelly on top, and many many other delicious dainties it would take too long to tell about passed before her active little mind. For some years now, Adelaide's mother had been using a small thin glass for her red currant jelly, and any other jelly of which she was especially choice. A glass measuring cup full of jelly was sufficient to fill three of these dainty glasses, and the beauty of these lay in the fact that you could put them on the table as they were. One little glass was sufficient to serve as a relish with cold meat or chicken for a family of four.

Mother thought that as Adelaide's quantities were all small she would let her use these small glasses exclusively for her jellies. Adelaide was delighted, and often held the little glasses up to the sunlight to see how clear and attractive the jelly was.

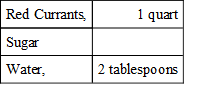

Red Currant Jelly

The large cherry currants were the ones mother bought, and she told Adelaide that they made the most delicious jelly. Adelaide emptied the currants into the colander, which she dipped up and down in a pan of clear cold water until the currants were thoroughly cleansed, then she drained them.

Picking them over but not removing the stems, Adelaide poured a few at a time into the saucepan (which contained two tablespoons of cold water), and mashed them with the wooden potato masher; this she continued to do until all the currants were used.

Placing the saucepan over the fire, she let the currants cook slowly until they looked white, stirring occasionally with the wooden spoon to prevent burning.

The little jelly bag attached to the wire frame fitted nicely over another large saucepan, and into this bag Adelaide poured the currants, letting them stand until all the juice had dripped.

Now she measured the juice and returned it to the original saucepan, which had been washed clean. Again she placed the saucepan over the fire and brought the juice to the boiling point; then she let it continue to boil rapidly for twenty minutes (mother said it was not necessary to stir this).

When Adelaide measured the juice she also measured to each cupful a cup of sugar. This she placed in an earthenware dish at the back of the range, or in the oven with the door open, to let it heat through gradually but not to brown. As soon as the juice had boiled sufficiently she added the heated sugar gradually and stirred with the wooden spoon until it was all dissolved; when it again came to the boiling point it jellied in about three minutes.

Adelaide worked very quickly now; she removed the saucepan from the fire, skimmed the jelly, poured it into a pitcher, and from there into the little sterilized glasses. These she placed in the sun and let them stand until the next day; they were then wiped around the tops and outsides carefully with a clean damp cloth, the jelly was covered with melted paraffin, the glass being shaken gently from side to side to exclude all air. Next came the labels, and then the jelly was stored away in the preserve closet. It was a beautiful color, and it made Adelaide's mouth water just to look at it.

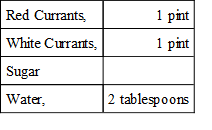

Red Currant and White Currant Jelly

The red and white currants Adelaide found made the jelly a beautiful color and more delicate in flavor. These she washed carefully in the colander by dipping it up and down in a pan of clear cold water, then she picked them over without removing the stems. Into the saucepan she measured two tablespoons of water, added the currants a few at a time, and mashed them with the wooden potato masher until all were used. Next the saucepan was placed over the fire and the currants boiled until the red currants looked white. Adelaide did not forget to stir with the wooden spoon to prevent the currants from burning.

The jelly bag was ready and into this Adelaide poured the currants. She let the juice drip overnight, and the next morning measured it into the saucepan. To each cup of juice she measured a cup of sugar, which she placed in an earthenware dish on the back of the range to heat through, but not to brown. The juice Adelaide boiled for twenty minutes rapidly, then she added the sugar very gradually and stirred until it was dissolved. When it came to the boiling point it "jellied" very quickly, and Adelaide skimmed it, poured it into a pitcher, then into the small glasses at once, which were already sterilized.

Standing them in a sunny window she let them remain until the next day. With a clean damp cloth she wiped the top and outside of each glass carefully, poured melted paraffin over the jelly, shook each glass gently from side to side to exclude the air, pasted on the labels and, as usual, stored the jelly away in the preserve closet.

Red Currant and Raspberry Jelly

Of all the jellies this was mother's favorite.

Adelaide picked over the raspberries (looking in each centre to be sure there were no little worms), poured them into the colander, dipped them up and down in a pan of clear cold water to cleanse thoroughly, and after draining emptied them into the saucepan with two tablespoons of cold water. The currants were washed in the same manner as the raspberries, and Adelaide picked them over but did not remove the stems. These were added to the raspberries, and she mashed them all with the wooden potato masher.