полная версия

полная версияThe 56th Division

Then Sapper Hawkins ran to the bank and threw a rope to Cox. This wonderful man still had the strength to hold on to it while Hawkins drew him ashore.

Cox died two days later!

McPhie was awarded the Victoria Cross.

* * * * * * *In this very fine enterprise 3 officers and 87 other ranks formed the attacking party. Altogether 6 officers and 165 other ranks passed over the canal. But this small force captured 4 officers and 203 other ranks. The casualties suffered by the whole of the 2nd Londons during the day were 3 officers and 140 other ranks.

Until the 169th Brigade handed over to the 10th Canadian Infantry Brigade, on the 14th October, they held the bridgehead and patrolled the north bank of the canal. But on the 15th the Germans succeeded in rushing the bridgehead, although they failed to get any identification.

On relief the 169th Brigade moved back to Sauchy-Cauchy, and the 168th, who were in reserve, entrained for Arras. On the 15th the 167th Brigade was relieved by the 11th Canadian Brigade and moved to Rumancourt. On the 16th the whole division was in the outskirts of Arras with headquarters at Etrun (except the artillery).

10. Battle of the Canal du Nord.

All through these weeks of fighting a great strain had been imposed on the Royal Army Service Corps and the Divisional Ammunition Column. The roads were bad and fearfully congested, and the distances were great and continually changing. When the great advance commenced railhead was at a place called Tincques; on the 23rd August it changed to Gouy-en-Artois; on the 27th to Beaumetz; on the 31st to Boisleux-au-Mont. On the 8th September it was at Arras and on the 11th October at Quéant. Not for one moment had supplies failed to be up to time. The work of this branch of the organisation was excellent, and the work of these units of supply should always be borne in mind in every account of actions fought and big advances made.

The artillery remained in the line until the 23rd October, and then rested in the neighbourhood of Cambrai until the 31st October.

* * * * * * *The whole of the Hindenburg Line passed into our possession during the early part of October, and a wide gap was driven through such systems of defence as existed behind it. The threat at the enemy’s communications was now direct. There were no further prepared positions between the First, Third, and Fourth Armies and Maubeuge.

In Flanders the Second Army, the Belgian Army, and some French divisions, the whole force under the King of the Belgians, had attacked on the 28th September, and were advancing rapidly through Belgium.

Between the Second Army, the right of the Flanders force, and the First Army, the left of the main British attacking force, was the Fifth Army under Gen. Birdwood. This army was in front of the Lys salient, which was thus left between the northern and southern attacks with the perilous prospect of being cut off. On the 2nd October the enemy started an extensive withdrawal on the Fifth Army front.

Meanwhile the Belgian coast was cleared. Ostend fell on the 17th October, and a few days later the left flank of the Allied forces rested on the Dutch frontier. The Fourth, Third, and First Armies still pushed on towards Maubeuge, and by the end of the month the Forêt de Mormal had been reached.

The enemy was thoroughly beaten in the field. Though he blew up the railways and roads as he fled, he was becoming embarrassed by his own rearguards pressing on his heels as they were driven precipitately before the Allied infantry; and the position of his armies revealed certain and overwhelming disaster.

* * * * * * *On the 27th October Austria sued for peace.

On the 28th the Italians crossed the Piave.

On the 29th the Serbians reached the Danube.

On the 30th October Turkey was granted an armistice.

The Central Powers lay gasping on the ground.

* * * * * * *The 56th Division meanwhile led a quiet life, training and resting round Etrun and Arras. Organisation of battalions was overhauled in accordance with a pamphlet numbered O.B./1919 and issued by the General Staff. It was designed to deal with the decreasing strength of battalions, but, as it supposed a greater number of men than were in many cases available, it was troublesome.

The outstanding points were that platoons would now be composed of two rifle and two Lewis-gun sections; that a platoon, so long as it contained two sections of three men each, was not to be amalgamated with any other platoon; and that not more than six men and one non-commissioned officer to each section should be taken into action.

“The fighting efficiency of the section,” says the pamphlet, “is of primary importance, and every endeavour must be made to strengthen the sections, if necessary, by the recall of employed men and men at courses, or even by withdrawing men from the administrative portions of battalion and company headquarters, which must in an emergency be temporarily reduced. After the requirements of the fighting portion for reconstruction have been met (50 other ranks), if the battalion is up to its full establishment, a balance of 208 men will remain for the administrative portion (90) and for reinforcements. This balance will include men undergoing courses of instruction, men on leave and in rest camps, men sick but not evacuated, and men on army, corps, divisional, or brigade employ. These latter must be reduced to the lowest figure possible, and will in no case exceed 30 men per battalion.”

The order against the amalgamation of platoons applied also to sections, but was not invariably carried out by company commanders. It had become a universal practice to detail six men and one non-commissioned officer to each post. With double sentries this gave each man one hour on and two hours off—anything less than these numbers threw a big strain on the men; and so long as the company commander had sufficient men for an adequate number of sentry posts, he made them up of that number.

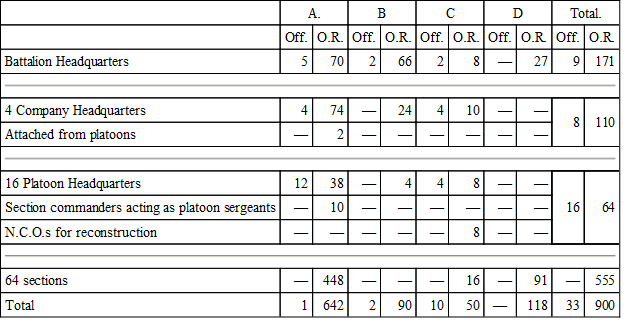

The details of a battalion as arranged by this pamphlet are interesting:

[Header Key:

A – Fighting position.

B – Administrative position.

C – Reconstruction (not for reinforcement).

D – Supplies for reinforcement.]

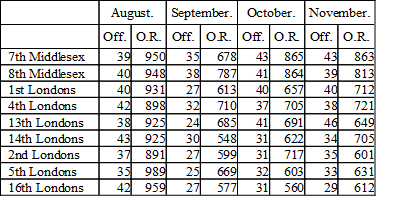

It will be seen that 732 other ranks were required to fill the fighting and administrative minimum. The ration strength of battalions from the 1st August and on the first of each month to the date of the armistice was:

But these figures must be read with a reservation. In spite of all efforts, men always disappeared. No battalion or company commander ever had the men who were on the ration strength. Guards, fatigue parties, sudden demands for men from higher commands, dozens of reasons could be given for the evaporation of strength. Probably two-thirds only of these men were really available for fighting. In those days a general when inspecting companies had no difficulty in finding fault if he wished to do so.

During the rest Gen. Hull discussed the subjects of organisation and training with the officers of each of his brigades.

But in the evening officers and men could be cheered by “Bow Bells,” which were to be heard at the theatre in Arras and the cinema at Haut Avesnes.

On the 31st the division moved into XXII Corps Reserve with headquarters at Basseville, and on the 1st November was ordered to relieve the 49th Division during the night 2nd/3rd.

On the 31st October the line immediately south of Valenciennes rested on the 4th Canadian Division, from the Canal de l’Escaut to the outskirts of the village of Famars, the 49th Division, on the high ground west of the River Rondelle, the 4th Division, astride the river and to the east of Artres, and then the 61st Division.

The 4th and 49th Divisions of the XXII Corps attacked on the 2nd November with the object of capturing the two villages of Preseau and Saultain, but only the first was taken, and the 49th Division held the Preseau-Valenciennes road.

The 56th Division was now plunged into real open fighting. Their objectives were no longer trench lines, but tactical features, such as spurs, rivers, woods, and villages. An examination of Gen. Hull’s operation orders reveals the new nature of the fighting.

The 169th Brigade was given the right and the 168th the left. The objective of the XXII Corps, which was attacking with the 11th Division on the right and the 56th on the left, was given as the “general line of the Aunelle River left bank.” The Canadian Corps would cover the left flank of the 56th Division by the capture of Estreux. The division would be covered by six brigades of field artillery.

On attaining the high ground on the left of the Aunelle River, patrols would be pushed out, “since if there is any sign of enemy retreat the G.O.C. intends to push on mounted troops to secure the crossing of the Petite Aunelle River and will order the leading brigades to support them.” The mounted troops referred to were two squadrons of Australian Light Horse.

Each of the attacking brigades had at the disposal of the Brigadier a battery of field artillery, also two sections (8 guns) of the M.G. Battalion.

As the front to be covered by the 56th Division was very extensive, the 146th Brigade, of the 49th Division, remained in line on the left, and was to advance until squeezed out by the converging advance of the 56th and Canadian Divisions.

On the night 2nd/3rd November the 169th and 168th Brigades relieved the right of the 49th Division on the Preseux-Valenciennes road without incident. Soon after 8 a.m. on the 3rd, patrols reported that the enemy had retired. The two brigades advanced and occupied Saultain, which was full of civilians, before mid-day. The cavalry and a company of New Zealand Cyclists were then ordered to push forward and secure the crossings of the River Aunelle. The line of the left bank of the river was reached at 6 p.m., where machine-gun fire was encountered. The brigades remained on that line for the night.

The advance was resumed at dawn on the 4th, when the Queen’s Westminster Rifles crossed the River Aunelle and captured the village of Sebourg; there was some half-hearted opposition from about thirty of the enemy who were rounded up, but when they attempted to advance east of the village they came under intense machine-gun and rifle fire from the high ground. Attempt to turn the enemy flank met with no success, and as there was no artillery barrage arranged, Brig.-Gen. Coke contented himself by holding the road to the east of the village.

The 168th Brigade on the left were also held up by the enemy on the high ground. The 4th London Regt. led the attack and took the hamlet of Sebourtquiaux (slightly north of Sebourg), only to find that they were not only faced with the enemy on the high ground to the east, but that heavy enfilade fire was being directed on them from the village of Rombies, on the western bank of the river, and on the Canadian Corps front. The 4th London Regt. took up a position to the east of Sebourtquiaux and astride the river, and so remained for the night. (Battle of the Sambre.)

This attack had been made without artillery preparation, but the position of the artillery is well described by Brig.-Gen. Elkington in a short report drawn up at the end of the operations. He says the barrage put down on the 1st November had been a very heavy one, and that the enemy never again waited for the full weight of the artillery to get into action.

“The problem for the artillery then became a matter of dealing with machine-gun nests, isolated guns, and small parties of the enemy who were delaying our advance and enabling the main body of the enemy to retire. The enemy blew up bridges and roads, whenever possible, to delay the advance of our guns. In these circumstances the following points were emphasised:

(1) The benefit of allotting artillery to each battalion commander in the front line. The battery commander, by remaining with the battalion commander and keeping good communication with his battery, could bring fire to bear at very short time on targets as they were encountered. In practice it was generally found that a full battery was too large a unit, and that four guns, or even a section, was of more use.

(2) When more than one artillery brigade was available for an infantry brigade, the necessity of keeping them écheloned in depth and maintaining all but one brigade on wheels. If resistance was encountered, the brigade, or brigades, on wheels in rear could be moved up to reinforce the artillery in the line to put down a barrage for an attack, or, if no resistance was encountered, a brigade in rear could advance through the artillery in action, which in turn could get on wheels as the advancing brigade came into action. This procedure enabled brigades to get occasional days’ rests and obviated the danger of getting roads choked with advancing artillery.

(3) The necessity of impressing on infantry commanders that though at the commencement of an attack it is possible to support them with a great weight of artillery, it is not possible to push this mass of artillery forward when movement becomes rapid, and that if they push forward rapidly, they are better served by a small mobile allotment of guns.”

The rapidity of the advance was little short of marvellous, for one must remember that it did not depend on the ability of the infantry to march forward, but on the engineers behind them, who were reconstructing the roads and railways for the supply services. Lieut.-Col. Sutton, who was controlling the Quartermasters’ Branch of the division, has a note in his diary:

“The enemy has done his demolition work most effectively. Craters are blown at road junctions and render roads impassable, especially in villages, where the rim of the crater comes in many cases up to the walls of the houses. Culverts are blown on main roads, and a particularly effective blockage is caused in one place by blowing a bridge across a road and stream, so that all the material fell across the road and in the river.”

This demolition was the great feature of the advance. The infantry could always go across country, but guns and lorries were not always able to use these short cuts. The weather was unfavourable, as it rained practically every day. When craters were encountered, the leading vehicles could perhaps get round, by going off the road, but they had the effect of churning up the soft ground so that the crater soon became surrounded by an impassable bog. The engineers and 5th Cheshires worked like Trojans to fill up these terrific pits, or make a firm surface round them.

At this date railhead was at Aubigny-au-Bac, the scene of that great exploit of the 2nd London Regt. And when one takes into account dates and distances, the achievement of those who were working behind the infantry must be ranked as one of the finest in the war. One cannot get a picture of the advance by considering the mere width of an army front. The infantry were the spearhead, the supplies the shaft, but the hand that grasped the whole weapon and drove it forward was that of the engineer, the pioneer, the man of the Labour Battalion. The effort of the army then must be considered in depth, from the scout to the base.

Under these circumstances communication between units became a matter of vital importance. The ordinary administrative routine of trench warfare required little modification, up to the point of the break through the Hindenburg Line—after that it became impossible. Brigade Headquarters were responsible for the distribution of rations, engineer material, ordnance, mails, and billeting. In the orders for advance the General Staff informed the Brigadier-General what units, or portion of divisional troops, including Divisional Artillery, would be under his tactical control, and these units, irrespective of their arm of the service, constituted the Brigade Group. The supply of ammunition, on the other hand, was worked by arms of the service and not by Brigade Groups. The channel of supply being the ordinary one—from the Divisional Ammunition Column to batteries, or Infantry Brigade Reserve, or Machine-gun Battalion Reserve.

* * * * * * *The administrative instructions for the division point out:

“The outstanding difficulty in all the administrative services will be that of intercommunication between the troops and the échelons in rear which supply them. The system of interchange of orderlies between the forward and rear échelons has been found unsatisfactory, as if the two échelons both move at the same time, all touch is lost. Prior to the advance, therefore, the administrative staff of each brigade group will fix a ‘meeting-point’ or ‘rear report centre’ as far forward as possible on the probable line of advance. This point will serve as a rendezvous for all maintenance service.... The principle of intercommunication by means of a fixed report centre will also be adopted by Divisional Artillery and the Machine Gun Battalion for the purpose of ammunition supply.”

This arrangement does not seem to have worked well for the artillery, as we find Brig.-Gen. Elkington reporting:

“For a time communication by orderly between units became the only feasible plan. Owing to the rapid movement these orderlies had the utmost difficulty in locating units. In this Divisional Artillery the system of using village churches as report centres was successfully tried, but, owing to the cessation of hostilities, the trial was not as exhaustive as could be wished. Notices showing change of location were simply stuck on the church doors or railings, and orderlies were instructed to at once proceed to the church for information on entering a village.”

This modification of the original scheme would seem to be a useful one.

In spite of all these difficulties, the 56th Division was advancing. On the 5th November a barrage was arranged to cover troops attacking the high ground to the east of the River Aunelle, as a preliminary to subsequent advance. The London Rifle Brigade led the attack of the 169th Brigade at 5.30 a.m., and by 7.30 a.m. had captured the village of Angreau. Here they were checked by the enemy, who occupied the woods on both banks of the Honnelle River. On their right the 11th Division captured the village of Roisin, but on their left the 168th Brigade had not made such good progress.

Attacking, with the London Scottish on the right and the Kensingtons on the left, the 168th Brigade were much hampered by flank fire from Angre and the ground to their left, which was still held by the enemy. The situation was somewhat eased by the capture of Rombies, by the 4th Canadian Division, and at 3 p.m. the artillery put down a rolling barrage, behind which the Kensingtons, and the London Scottish on their right, advanced to the outskirts of Angre. The position for the night was on the high ground west of the River Grande Honnelle.

The enemy had determined to defend the crossing of the river, and had an excellent position on the eastern bank, where they held the Bois de Beaufort in strength. The advance was to be resumed at 5.30 a.m., but just before that hour the German artillery put down a heavy barrage of gas-shells. Undaunted, the 2nd Londons on the right and the London Rifle Brigade on the left of the 169th Brigade attacked in gas-masks and crossed the river. The 168th Brigade, attacking with the London Scottish and Kensingtons in line, met at first with slight resistance, but as soon as the river was reached they were faced with a heavy barrage of artillery and machine-gun fire. In spite of very accurate fire, they succeeded in crossing the river to the north and south of Angre. The position in front of them was of considerable natural strength, but was turned by a clever move of the London Scottish from the south, which established them firmly on the east bank. The Kensingtons advanced to the high ground immediately east of the village of Angre, and here met a heavy counter-attack which drove them back to the west bank.

Meanwhile the 169th Brigade was engaged in heavy fighting. Only the northern portion of the Bois de Beaufort was included in the attack, and the enemy were found to be strongly situated on ground which dominated the western bank of the river. The attack was delivered with spirit, and the enemy driven back. The 2nd Londons had the wood in front of them, and the London Rifle Brigade shot ahead on the left, outside the wood. The enemy rallied and counter-attacked the forward troops, while at the same time a force of Germans debouched from the wood on the right flank of the Rifle Brigade men, who were driven back to the west of the river. Some of the 2nd Londons were involved in this successful enemy counter-attack, but a party of forty—a large party in those days—held on to the position they had reached in the Bois de Beaufort until late in the afternoon, when, discovering what had happened on the left, and being almost entirely surrounded, they retired fighting to the western bank of the river.

The right brigade, therefore, remained on the west bank. The casualties had been heavy, amounting to 394.

The London Scottish had retained their hold of the east bank, and later in the afternoon the Kensingtons again succeeded in crossing the river, and definitely established themselves to the east and in touch with the London Scottish. The casualties of the 168th Brigade during these operations were 207. The prisoners captured by them were 111. The prisoners captured by the 169th Brigade were 43.

The general destruction of roads, combined with the vile weather, now began to cause anxiety. Horses were used as much as possible—a horse can drag a cart through places which would be impossible for a motor lorry—and civilian wagons were pressed into service, being used in conjunction with spare army horses. This was all the more necessary as the administrative branch of the division had the additional responsibility of feeding civilians.

All the villages captured or occupied by the troops were filled with civilians. So great was their emotion on their release that they pressed whatever they had in the nature of food and drink on the troops. The coffee-pot of the French or Belgian housewife was replenished with reckless disregard for “to-morrow.” And then as the country was regained, so the villagers were cut off from the source which had provided them with their limited supplies. With Germans in retreat on one side and roads blown up on the other, they were more isolated than they had ever been. On the 6th November the 56th Division was rationing 16,000 civilians, and most of this work was being done by the transport of the 168th and 169th Brigades.

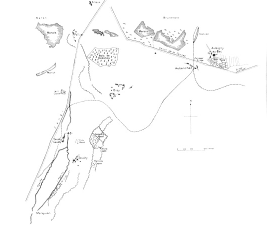

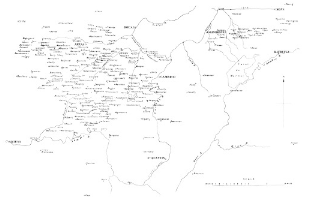

11. General Map.

The battle on the right of the division had progressed with almost unfailing success. The 11th Division on their immediate right had met with the same check on the River Honnelle, but farther south the Army had forced their way through the great Forest of Mormal, and troops were well to the east of it. The German rearguards were only able, on especially favourable positions, to check the advance of a few divisions; on the whole the rearguards were being thrown back on the main retreating force. The roads were packed with enemy troops and transport, and the real modern cavalry, the low-flying aeroplanes, swooped down on them, with bomb and machine gun spreading panic and causing the utmost confusion.

During the night 6th/7th November the 63rd Division was put into line on the front of the 168th Brigade, and the 169th was relieved by the 167th Brigade. The 56th Division was then on a single brigade front, with the 11th Division on the right and the 63rd on the left.

At dawn on the 7th patrols found that the enemy was still in front of them, and at 9 a.m. the brigade attacked with the 8th Middlesex on the right and the 7th Middlesex on the left. They swept on through the northern part of the wood, and by 10.30 a.m. the 7th Middlesex entered the village of Onnezies. The Petite Honnelles River was crossed, and the village of Montignies taken in the afternoon. But after the Bavai-Hensies Road was crossed, opposition stiffened, and both artillery and machine-gun fire became severe. A line of outposts held the east of the road for the night.