полная версия

полная версияThe Eighteen Christian Centuries

1st. From this it will result, that, to keep reformed England secure, it was indispensable to have reformed Scotland on her side.

2d. That, in order to have Scotland either reformed or on her side, it was indispensable to render powerless a popish queen,—a queen who was supported as legitimate inheritor of England by the Pope and Philip of Spain, and the King and princes of France.

3d. That Elizabeth had a right, by all the laws of self-preservation, to sustain by every legal and peaceable means that party in Scotland which was de facto the government of the country, and which promised to be most useful to the objects she had in view. Those objects have already been named,—peace and security for the Protestant religion, and the honour and independence of the whole British realm.

To gain these ends, who denies that she bribed and bullied and deceived?—that she degraded the Scottish nobles by alternate promises and threats, and weakened the Scottish crown by encouraging its enemies, both ecclesiastical and civil? In prudishly finding fault with these proceedings, we forget the Scotch, French, Spanish, popish, emissaries who were let loose upon England; the plots at home, the scowling messages from abroad; the excommunications uttered from Rome; the massacre of the Protestants gloried in in France, and the vast navies and immense armies gathering against the devoted Isle from all the coasts and provinces of Spain.

In 1568, after the defeat of the queen’s party at Langside, Mary threw herself on the pity and protection of Elizabeth, and was kept in honourable safety for many years. She did not allow her to collect partisans for the recovery of her kingdom, nor to cabal against the government which had expelled her. To do so would not have been to shelter a fugitive, but to declare war on Scotland. In 1848, Louis Philippe, chased by the revolutionists of Paris, came over to England. He was kept in honourable retirement. He was not allowed to cabal against his former subjects, nor to threaten their policy. To do so would not have been to shelter a fugitive, but to declare war on France. Even in the case of the earlier Bourbons, we permitted no gatherings of forces on their behalf, and did not encourage their followers to molest the settled government,—no, not when the throne of France was filled by an enemy and we were at deadly war with Napoleon. But Mary was put to death. A sad story, and very melancholy to read in quiet drawing-rooms with Britannia ruling the waves and keeping all danger from our coasts. But in 1804, if Louis the Eighteenth or Charles the Tenth, instead of eating the bread of charity in peace, had been detected in conspiracy with our enemies, in corresponding with foreign emissaries, when a thousand flat-bottomed boats were marshalling for our invasion at Boulogne, and Brest and Cherbourg and Toulon were crowded with ships and sailors to protect the flotilla, it needs no great knowledge of character to pronounce that English William Pitt and Scottish Harry Dundas would have had the royal Bourbon’s head on a block, or his body on Tyburn-tree, in spite of all the romance and eloquence in the world.

Mary’s guilt or innocence of the charges brought against her in her relations with Darnley and Bothwell has nothing to do with the treatment she received from Elizabeth. She was not amenable to English law for any thing she did in Scotland, nor was she condemned for any thing but treasonable practices which it was impossible to deny. She certainly owed submission and allegiance to the English crown while she lived under its protection. Let us indulge our chivalrous generosity, and enjoy delightful poems in defence of an unfortunate and beautiful sovereign, by believing that the blots upon her fame were the aspersions of malignity and political baseness: the great fact remains, that it was an indispensable incident to the security of both the kingdoms that she should be deprived of authority, and finally, as the storm darkened, and derived all its perils from her conspiracies against the State and breaches of the law, that she should be deprived of life. Far more sweeping measures were pursued and defended by the enemies of Elizabeth abroad. Present forever, like a skeleton at a feast, must have been the massacre of St. Bartholomew in the thoughts of every Protestant in Europe, and most vividly of all in those of the English queen. That great blow was meant to be a warning to heretics wherever they were found, and in olden times and more revengeful dispositions might have been an excuse for similar atrocity on the other side. The Bartholomew massacre and the Armada are the two great features of the latter part of this century; and they are both so well known that it will be sufficient to recall them in a very few words.

This massacre was no chance-sprung event, like an ordinary popular rising, but had been matured for many years. The Council of Trent, which met in 1545 and continued its sittings till 1563, had devoted those eighteen years to codifying the laws of the Catholic Church. A definite, clear, consistent system was established, and acknowledged as the religious and ecclesiastical faith of Christendom. Men were not now left to a painful gathering of the sentiments and rescripts of popes and doctors out of varying and scattered writings. Here were the statutes at large, minutely indexed and easy of reference. From these many texts could be gathered which justified any method of diffusing the true belief or exterminating the false. And accordingly, a short time after the close of the Council, an interview took place between two personages, of very sinister augury for the Protestant cause. Catherine de Medicis and the Duke of Alva met at Bayonne in 1565. In this consultation great things were discussed; and it was decided by the wickedest woman and harshest man in Europe that government could not be safe nor religion honoured unless by the introduction of the Inquisition and a general massacre of heretics in every land. A few months later saw the ferocious Alva beginning his bloodthirsty career in the Netherlands, in which he boasted he had put eighteen thousand Hollanders to death on the scaffold in five years. Catherine also pondered his lessons in her heart, and when seven years had passed, and the Huguenots were still unsubdued, she persuaded her son Charles the Ninth that the time was come to establish his kingdom in righteousness by the indiscriminate murder of all the Protestants. An occasion was found in 1572, when the marriage of Henry of Navarre, afterwards the best-loved king of France, with the Princess Margaret de Valois, held out a prospect of soothing the religious troubles, and also (which suited her designs better) of attracting all the heads of the Huguenot cause to Paris. Every thing turned out as she hoped. There had been feasts and gayeties, and suspicion had been thoroughly disarmed. Suddenly the tocsin was sounded, and the murderers let loose over all the town. No plea was received in extenuation of the deadly crime of favouring the new opinions. Hospitality, friendship, relationship, youth, sex, all were disregarded. The streets were red with blood, and the river choked with mutilated bodies. Upwards of seventy thousand were butchered in Paris alone, and the metropolitan example was followed in other places. The deed was so awful that for a while it silenced the whole of Europe. Some doubted, some shuddered; but Rome sprang up with a shout of joy when the news was confirmed, and uttered prayers of thanksgiving for so great a victory. If it could have been possible to put every gainsayer to death everywhere, the triumph would have been complete; but there were countries where Catherine’s dagger could not reach; and whenever her name was heard, and the terrible details of the massacre were known, undying hatred of the Church which encouraged such iniquity mingled with the feelings of pity and alarm. For no one henceforth could feel safe. The Huguenots were under the highest protection known to the heart of man. They were guests, and they were taken unawares in the midst of the rejoicings of a marriage. Rome lost more by the massacre than the Protestants. People looked round and saw the butcheries in the Netherlands, the slaughters in Paris, the tortures in the Inquisition, and over all, rioting in hopes of recovered dominion, supported by his priests and Dominicans, a Pope who plainly threatened a repetition of such scenes wherever his power was acknowledged. Germany, the Netherlands, England, Scotland, and the Northern nations, were lost to the Church of Rome more surely by the scaffold and crimes which professed to bring her aid, than by any other cause. Elizabeth was now the accepted champion and leader of the Protestants, and on her all the malice of the baffled Romanists was turned. To weaken, to dethrone or murder the English heretic was the praiseworthiest of deeds.

But one great means of distracting England from her onward course was now removed. In former days Scotland would have been let loose upon her unguarded flanks; but by this time the genius of Knox, running parallel with the efforts of the Southern reformers, had raised a religious feeling which responded to the English call. Scotland, freed from an oppressive priesthood, did manful battle at the side of her former enemy. Elizabeth was kept safe by the joint hatred the nations entertained to Rome, and, as regarded foreigners, the Union had already taken place. On one sure ground, however, those foreigners could still build their hopes. Mary, conscientious in her religion, and embittered in her dislike, was still alive, to be the rallying-point for every discontented cry and to represent the old causes,—the legitimate descent and the true faith. The greatest circumspection would have been required to keep her conduct from suspicion in these embarrassing circumstances. But she was still as thoughtless as in her happier days, and exposed herself to legal inquiries by the unguardedness of her behaviour. The wise counsellors of Elizabeth saw but one way to put an end to all those fears and expectations; and Mary, after due trial, was condemned and executed. |A.D. 1587.|Hope was now at an end; but revenge remained, and the great Colossus of the Papacy bestirred himself to punish the sacrilegious usurper. Philip the Second was still the most Catholic of kings. More stern and bigoted than when he had tried to restrain the burning zeal of Mary of England, he was resolved to restore by force a revolted people to the Chair of St. Peter and exact vengeance for the slights and scorns which had rankled in his heart from the date of his ill-omened visit. He prepared all his forces for the glorious attempt. Nothing could have been devised more calculated to bring all English hearts more closely to their queen. Every report of a fresh squadron joining the fleets already assembled for the invasion called forth more zeal in behalf of the reformed Church and the undaunted Elizabeth. Scotland also held some vessels ready to assist her sister in this great extremity, and lined her shores with Presbyterian spearmen. Community of danger showed more clearly than ever that safety lay in combination. Chains, we know, were brought over in those missionary galleys, and all the apparatus of torture, with smiths to set them to work. But the smiths and the chains never made good their landing on British ground. The ships covered all the narrow sea; but the wind blew, and they were scattered. It was perhaps better, as a warning and a lesson, that the principal cause of the Spaniard’s disaster was a storm. If it had been fairly inflicted on them in open battle, the superior seamanship or numbers or discipline of the enemy might have been pleaded. But there must have mingled something more depressing than the mere sorrow of defeat when Philip received his discomfited admiral with the words, “We cannot blame you for what has happened: we cannot struggle against the will of God.”

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

Bacon, Milton, Locke, Corneille, Racine, Molière, Kepler, (1571-1630,) Boyle, (1627-1691,) Bossuet, (1627-1704,) Newton, (1642-1727,) Burnet, (1643-1715,) Bayle, (1647-1706,) Condé, Turenne, (1611-1675,) Marlborough, (1650-1722.)

THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

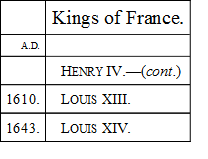

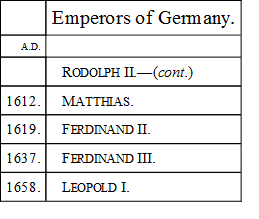

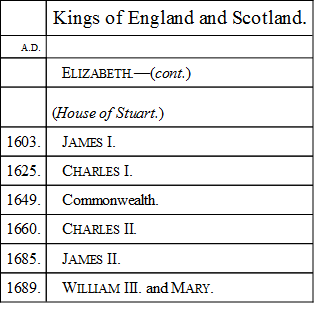

ENGLISH REBELLION AND REVOLUTION – DESPOTISM OF LOUIS THE FOURTEENTHWe are apt to suppose that progress and innovation are so peculiarly the features of these latter times that it is only in them that a man of more than ordinary length of life has witnessed any remarkable change. We meet with men still alive who were acquainted with Franklin and Voltaire, who have been presented at the court of Louis the Sixteenth and have visited President Pierce at the White House. But the period we have now to examine is quite as varied in the contrasts presented by the duration of a lifetime as in any other age of the world. Of this we shall take a French chronicler as an example,—a man who was as greedy of news, and as garrulous in relating it, as Froissart himself, but who must take a very inferior rank to that prose minstrel of “gentle blood,” as he limited his researches principally to the scandals which characterized his time. We mean the truth-speaking libeller Brantôme. |A.D. 1616.|This man died within a year or two of Shakspeare, and yet had accompanied Mary to Scotland, and given that poetical account of the voyage from Calais, when she sat in the stern of the vessel with her eyes fixed on the receding shore, and said, “Adieu, France, adieu! I shall never see you more;” and again, on the following morning, bending her looks across the water when land was no longer to be seen, and exclaiming, “Adieu, France! I shall never see you more.” The mere comparison of these two things—the return of Mary to her native kingdom, torn at that time with all the struggles of anarchy and distress, and the death of the greatest of earth’s poets, rich and honoured, in his well-built house at Stratford-on-Avon—suggests a strange contrast between the beginning of Brantôme’s literary career and its close: the events filling up the interval are like the scarcely-discernible heavings in a dark and tumultuous sea,—a storm perpetually raging, and waves breaking upon every shore. In his own country, cruelty and demoralization had infected all orders in the State, till murder, and the wildest profligacy of manners, were looked on without a shudder. Brantôme attended the scanty and unregretted funeral of Henry the Third, the last of the house of Valois, who was stabbed by the monk Jacques Clement for faltering in his allegiance to the Church. A sentence had been pronounced at Rome against the miserable king, and the fanatic’s dagger was ready. Sixtus the Fifth, in full consistory, declared that the regicide was “comparable, as regards the salvation of the world, to the incarnation and the resurrection, and that the courage of the youthful Jacobin surpassed that of Eleazar and Judith.” “That Pope,” says Chateaubriand, the Catholic historian of France, “had too little political conviction, and too much genius, to be sincere in these sacrilegious comparisons; but it was of importance to him to encourage the fanatics who were ready to murder kings in the name of the papal power.” Brantôme had seen the issuing of a bull containing the same penalties against Elizabeth, the death of Mary on the scaffold, and the failure of the Armada. After the horrors of the religious wars, from the conspiracy of Amboise in 1560 to the publication of the edict of toleration given at Nantes in 1598, he had seen the comparatively peaceful days of Henry the Fourth, till fanaticism again awoke a suspicion of a return to his original Protestant leanings, as shown in his opposition to the house of Austria, and Ravaillac renewed the meritorious work of Clement in 1610. Last of all, the spectator of all these changes saw England and Scotland forever united under one crown, and the first rise of the master of the modern policy of Europe, for in the year of Brantôme’s death a young priest was appointed Secretary of State in France, whom men soon gazed on with fear and wonder as the great Cardinal Richelieu.

In England the alterations were as great and striking. After the troubled years from Elizabeth’s accession to the Armada, a period of rest and progress came. Interests became spread over the whole nation, and did not depend so exclusively on the throne. Wisdom and good feeling made Elizabeth’s crown, in fact, what laws and compacts have made her successors’,—a constitutional sovereign’s. She ascertained the sentiments of her people almost without the intervention of Parliament, and was more a carrier-through of the national will than the originator of absolute decrees. The moral battles of a nation in pursuit of some momentous object like religious or political freedom bring forth great future crops, as fields are enriched on which mighty armies have been engaged. The fertilizing influence extends in every direction, far and near. If, therefore, the intellectual harvest that followed the final rejection of the Pope and crowning defeat of the Spaniard included Shakspeare and Bacon, and a host of lesser but still majestic names, we may venture also to remark, on the duller and more prosaic side of the question, that in the first year of the seventeenth century a patent was issued by which a commercial speculation attained a substantive existence, for the East India Company was founded, with a stock of seventy-two thousand pounds, and a fleet of four vessels took their way from the English harbours, on their first voyage to the realm where hereafter their employers, who thus began as merchant adventurers, were to rule as kings. The example set by these enterprising men was followed by high and low. During the previous century people had been too busy with their domestic and religious disputes to pay much attention to foreign exploration. They were occupied with securing their liberties from the tyranny of Henry the Eighth and their lives from the truculence of Mary. Then the plots perpetually formed against Elizabeth, by domestic treason and foreign levy, kept their attention exclusively on home-affairs. But when the State was settled and religion secure, the long-pent-up activity of the national mind found vent in distant expeditions. A chivalrous contempt of danger, and poetic longing for new adventure, mingled with the baser attractions of those maritime wanderings. The families of gentle blood in England, instead of sending their sons to waste their lives in pursuit of knightly fame in the service of foreign states, equipped them for far higher enterprises, and sent them forth to gather the riches of unknown lands beyond the sea. Romantic rumours were rife in every manor-house of the strange sights and inexhaustible wealth to be gained by undaunted seamanship and judicious treatment of the natives of yet-unexplored dominions. Spain and Portugal had their kingdoms, but the extent of America was great enough for all. Islands were everywhere to be found untouched as yet by the foot of European; and many a winter’s night was spent in talking over the possible results of sailing up some of the vast rivers that came down like bursting oceans from the far-inland regions to which nobody had as yet ascended,—the people and cities that lay upon their banks, the gold and jewels that paved the common soil. Towards the end of Elizabeth’s reign, these imaginings had grown into sufficing motives of action, and gentlemen were ready from all the ports of the kingdom to sail on their adventurous voyages. In addition to the chance those gallant mariners had of realizing their day-dreams by the tedious methods of discovery and exploration, there was always the prospect of making prize of a galleon of Spain; for at all times, however friendly the nations might be in the European waters, a war was carried on beyond the Azores. Not altogether lost, therefore, was the old knightly spirit of peril-seeking and adventure in those commercial and geographical speculations. There were articles of merchandise in the hold, gaudy-coloured cloths, and bead ornaments, and wretched looking-glasses, besides brass and iron; but all round the captain’s cabin were arranged swords and pistols, boarding-pikes, and other implements of fight. Guns also of larger size peeped out of the port-holes, and the crew were chosen as much with a view to warlike operations as to the ordinary duties of the ship. The Spaniards had made their way into the Pacific, and had established large settlements on the shores of Chili and Peru. Scenes which have been reacted at the diggings in modern times took place where the Europeans fixed their seat, and ships loaded with the precious metals found their way home, exposed to all the perils of storm and war. Drake had pounced upon several of their galleys and despoiled them of their precious cargo. Cavendish, a gentleman of good estate in Suffolk, had followed in his wake, and, after forcing his way through the Straits of Magellan, had reached the shores of California itself and there captured a Spanish vessel freighted with a vast amount of gold. All these adventures of the expiring sixteenth century became traditions and ballads of the young seventeenth. Raleigh, the most accomplished gentleman of his time, gave the glory of his example to the maritime career, and all the oceans were alive with British ships. While Raleigh and others of the upper class were carrying on a sort of cultivated crusade against the monopoly of the Spaniards, others of a less aristocratic position were busied in the more regular paths of commerce. We have seen the formation of the India Company in 1600. Our competitors, the Dutch, fitted out fleets on a larger scale, and established relations of trade and friendship with the natives of Polynesia and New Holland, and even of Java and India. But the zeal of the public in trading-speculations was not only shown in those well-conducted expeditions to lands easily accessible and already known: a company was established for the purpose of opening out the African trade, and a commercial voyage was undertaken to no less a place than Timbuctoo by a gallant pair of seamen of the names of Thomson and Jobson. It was not long before these efforts at honest international communication, and even the exploits of the Drakes and Cavendishes, who acted under commissions from the queen, degenerated into lawless piracy and the golden age of the Buccaneers. The policy of Spain was complete monopoly in her own hands, and a refusal of foreign intercourse worthy of the potentates of China and Japan. All access was prohibited to the flags of foreign nations, and the natural result followed. Adventurous voyagers made their appearance with no flag at all, or with the hideous emblem of a death’s head emblazoned on their standard, determined to trade peaceably if possible, but to trade whether peaceably or not. The Spanish colonists were not indisposed to exchange their commodities with those of the new-comers, but the law was imperative. The Buccaneers, therefore, proceeded to help themselves to what they wanted by force, and at length came to consider themselves an organized estate, governed by their own laws, and qualified to make treaties like any other established and recognised power. Cuba had been nearly depopulated by the cruelties and fanaticism of its Spanish masters, and was seized on by the Buccaneers. From this rich and beautiful island the pirate-barks dashed out upon any Spanish sail which might be leaving the mainland. Commanding the Gulf of Mexico, and with the power of crossing the Isthmus of Panama by a rapid march, those redoubtable bandits held the treasure-lands of the Spaniards in terrible subjection. And up to the commencement even of the eighteenth century the frightful spectacle was presented of a powerful confederacy of the wildest and most dissolute villains in Europe domineering over the most frequented seas in the world, and filling peaceful voyagers, and even well-armed men-of-war, with alarm by their unsparing cruelty, and atrocities which it curdles the blood to think of.

Eastward as far as China, westward to the islands and shores of the great Pacific, up the rivers of Africa, and even among the forests of New Holland and Tasmania, the swarms of European adventurers succeeded each other without cessation. The marvel is, that, with such ceaseless activity, any islands, however remote or small, were left for the discovery of after-times. But the tide of English emigration rolled towards the mainland of North America with a steadier flow than to any other quarter. The idea of a northwest passage to India had taken possession of men’s minds, and hardy seamen had already braved the horrors of a polar winter, and set examples of fortitude and patience which their successors, from Behrens to Kane, have so nobly followed. But the fertile plains of Virginia, and the navigable streams of the eastern shore, were more alluring to the peaceful and unenterprising settlers, whose object was to find a new home and carry on a lucrative trade with the native Indians. In 1607, a colony, properly so called,—for it had made provision for permanent settlement, and consisted of a hundred and ten persons, male and female,—arrived at the mouth of the Chesapeake. The river Powhatan was eagerly explored; and at a point sufficiently far up to be secure from sudden attack from the sea, and on an isthmus easily defended from native assault, they pitched their tents on a spot which was hereafter known as Jamestown and is still honoured as the earliest of the American settlements. Our neighbour Holland was not behindhand either in trade or colonization, and equally with England was excited to fresh efforts by its recovered liberty and independence. In all directions of intellectual and physical employment those two States went boundingly forward at the head of the movement. The absolute monarchies lay lazily by, and relied on the inertness of their mass for their defence against those active competitors; and Spain, an unwieldy bulk, showed the intimate connection there will always exist between liberal institutions at home and active progress abroad. The sun never set on the dominions of the Spanish crown, but the life of the people was crushed out of them by the weight of the Inquisition and despotism. The United Provinces and combined Great Britain had shaken off both those petrifying institutions, and Englishmen, Scotchmen, and Dutchmen were ploughing up every sea, presenting themselves at the courts of strange-coloured potentates, in regions whose existence had been unknown a few years before, and gradually accustoming the wealth and commerce of the world to find their way to London and Amsterdam.