полная версия

полная версияThe Eighteen Christian Centuries

This is one of the inventions apparently unimportant, by which incalculable results have been produced. At first it was intended merely to simplify the process of copying the books which were already well known. And, if we may trust some of the stories told of the earliest specimens of the art, we shall see that there was some slight portion of dishonesty mingled with the talent of the Fathers of printing. These were Guttenberg of Mentz, and his apprentice or partner Faust. |A.D. 1455.|The first of their productions was a Latin Bible; and the letters of this impression were such an exact imitation of the works of the amanuensis that they passed it off as an exquisite specimen of the copyist’s art. Faust sold a copy to the King of France for seven hundred crowns, and another to the Archbishop of Paris for four hundred. The prelate, enchanted with his bargain, (for the usual price was several hundred crowns above what he had given,) showed it in triumph to the king. The king compared the two, and was filled with astonishment. They were identical in every stroke and dot. How was it possible for any two scribes, or even for the same scribe, to produce so undeniable a fac-simile of his work? The capital letters of the edition were of red ink. They inquired still further, and found that many other copies had been sold, all precisely alike in form and pressure. They came to the conclusion that Faust was a wizard and had sold himself to the devil, and that the initials were of blood. The Church and State, in this case united in the persons of king and archbishop, had the magician apprehended. To save himself from the flames, the unhappy Faust had to confess the deceit, and also to discover the secret of the art. The whole mystery consisted in cutting letters upon movable metal types, and, after rubbing them with ink when they were correctly set, imprinting them upon paper by means of a screw. A simple expedient, as it appeared to everybody when the secret was spread abroad; for there had been seals stamping impressions on wax for many generations. Medals and coins had been poured forth from the dies of every nation from the dawn of history. In England, playing-cards had been produced for several years, with the figures impressed on them from wooden blocks; and in 1423 a stamped book, with wood engravings, had made its appearance, which now, with many treasures of typography, is in the library of Lord Spencer. Even in Nineveh, we learn from recent discovery, the dried bricks, while in a soft state, had been stamped with those curious-looking inscriptions, by a board in which the unsightly letters were set in high relief. Wooden letters had also long been known; and yet it was not till 1440 that Guttenberg bethought him of the process of printing, and only after ten or twelve years’ labour that he brought his experiments to perfection and with one crush of the completed press opened new hopes and prospects to the whole family of mankind. But things apparently unconnected are brought together for good when the great turning-points of human history are attained. There are always pebbles of the brook within reach when the warrior-shepherd has taken the sling in his hand. Shortly before the invention of printing, a discovery was made without which Guttenberg’s skill would have been of no avail. This was the applicability of linen rags to the manufacture of paper. Parchment, and preparations of straw and papyrus, had sufficed for the transcriber and author of those unliterary times, but would have been inadequate to supply the demand of the new process; and therefore we may say that, as gunpowder was essential to the use of artillery, and steam-power for the railway-train, linen paper was indispensable to the development of the press. And the development was rapid beyond all imagination. In the remaining portion of the century, eight thousand five hundred and nine books were published, of which the English Caxton and his followers supplied one hundred and forty-two,—a small contribution in actual numbers, but valuable for the insight it gives us into the favourite literature of the time. Among those volumes there are

“Songs of war for gallant knight,Lays of love for lady bright;”“The Tale of Troy divine,” for scholars; “Tullie, of old age,” and “of Friendship,” and “Virgil’s Æneid,” for the classical; “Lives of Our Ladie and divers Saints,” for the religious; and “The Consolation of Boethius,” for the afflicted. But several editions prove the popularity of the Father of English poetry; and we find the “Tales of Cauntyrburrie,” and the “Book of Fame,” and “Troylus and Cresyde, made by Geoffrey Chaucer,” the great and fitting representatives of the native English muse.

We ought to remember, in judging of the paucity of books produced in England, that the Wars of the Roses broke out at the very time when Guttenberg’s labours began. In such a season of struggle and unrest as the thirty years of civil strife—for though Mr. Knight, in his very interesting sketch of this date,[4] has shown that the period of actual and open war was very short, the state of uneasiness and expectation must have endured the whole time—there was small encouragement to the peaceful triumphs of art or literature. And, moreover, the pride of station was revolted by the prospect of the spread of information among the classes to whom it had not yet reached. The noble could afford to acknowledge his inferiority in learning and research to the priest or monk, for it was their trade to be wise and learned, and their scholarship was even considered a badge of the lowness of their birth, which had given them the primer and psalter instead of the horse and sword. But those high-hearted cavaliers could ill brook the notion of educated clowns and peasants. And, strange to say, the sentiment was shared and exaggerated by the peasants and clowns themselves. Jack Cade is represented, by an anachronism of date but with perfect truth of character, as profoundly irritated at the invention of printing, and the building of a paper-mill, and the introduction of such heathenish words as nominatives and adverbs: so that the press began its career opposed by the two greatest parties of the State. Yet truth is mighty and will prevail. No nobility in Europe gives such contributions to the general stock of high and healthy thought as the descendants of the men of Towton and Bosworth, and no peasantry values more deeply, or would defend more gallantly, the gifts poured upon it by a free and sympathizing press. Warwick the King-maker, if he had lived just now, would have made speeches in Parliament and had them reported in the Times, and Jack Cade would have been sent to the reformatory and taught to read and write.

But, with the peerages of Europe greatly thinned, with mounted feudalism overthrown, with the press rejoicing as a giant to run its course, something also was needed in order to make a wider theatre for the introduction of the new life of men. Another world lay beyond the great waters of the Atlantic. Whispers had been going round the circle of earnest inquirers, which gradually grew louder and louder till they reached the ears of kings, that great things lay hidden in the awful and mysterious solitudes of the ocean; that westward, to balance the preponderance of our used-up continent, must be solid land, equal in weight and size, so that the uninterrupted waters would conduct the adventurous mariner to the farther India by a nearer route than Bartholomew Diaz, the Portuguese, had just discovered. |A.D. 1487.|This man sailed to the southern extremity of Africa, passed round to the east without being aware of his achievement, and penetrated as far as Lagoa Bay. But the crew became discontented, and the navigator retraced his steps. Alarmed at the commotion of the vast waves of the Southern Ocean pouring its floods against the Table Mountain, he had retired from further research, and called the southern point of his pilgrimage the Cape of Storms. It is now known to us by a happier augury as the Cape of Good Hope. But, whether perpetually haunted by tempests or not, the truth was discovered that the land ceased at that promontory and left an unexplored sea beyond. This was cherished in many a heart; for in this century maritime discovery kept pace with the other triumphs of mental power. Wherever ship could swim man could venture. The Azores had been discovered in 1439 and colonized by the Portuguese in 1440. Already in possession of Cape Verd, Madeira, and the Canaries, Portugal looked forward to greater discoveries, for these were the nurseries of gallant and skilful mariners. But the glory was left for another nation,—though, by a strange caprice of fortune, the chance of it had been offered to nearly all.

The life of Columbus is more wonderful than a romance. He hawked about his notion of the way to India at all the courts of Europe. By birth a Genoese, he considered the great ocean the patrimony of any person able to seize it. When his services, therefore, were rejected by his own country, he offered them successively to Portugal, to Spain, and to England. Henry the Seventh was inclined to venture a small sum in the lottery of chances; but, while still in negotiation with the brother of Columbus, the Spanish monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, closed with the navigator’s terms, and on the 3d of August, 1492, the squadron of discovery, consisting of a vessel of some size, and two small pinnaces, with a crew at most of a hundred persons in all the three, sailed from the port of Palos, in Andalusia. Three weeks’ constant progress to the westward took them far beyond all previous navigation. The men became disheartened, discontented, and finally rebellious. Against all, Columbus bore up with the self-relying energy of a great mind, but was driven to the compromise of promising, if they confided in him for three days longer, he would return, if the object of his voyage was yet unattained. But by this time his sagacious observation had assured him of success. Strange appearances began to be perceived from the ship’s decks. A carved piece of wood floated past, then a reed newly cut, and, best sign of all, a branch with red berries still fresh. “From all these symptoms, Columbus was so confident of being near land, that on the evening of the 11th of October, after public prayers for success, he ordered the sails to be furled, and the ships to lie to, keeping strict watch, lest they should be driven ashore in the night. During this interval of suspense and expectation no man shut his eyes: all kept upon deck, gazing intently towards that quarter where they expected to discover the land, which had been so long the object of their wishes. About two hours before midnight, Columbus, standing on the forecastle, observed a light at a distance, and privately pointed it out to Pedro Guttierez, a page of the queen’s wardrobe. Guttierez perceiving it, and calling to Salcedo, comptroller of the fleet, all three saw it in motion, as if it were carried from place to place. A little after midnight the joyful sound of ‘Land! land!’ was heard from the Pinta, which kept always ahead of the other ships. But, having been so often deceived by fallacious appearances, every man was now become slow of belief, and waited in all the anguish of uncertainty and impatience for the return of day. As soon as morning dawned, all doubts and fears were dispelled. From every ship an island was seen about two leagues to the north, whose flat and verdant fields, well stored with wood, and watered with many rivulets, presented the aspect of a delightful country. The crew of the Pinta instantly began the Te Deum as a hymn of thanksgiving to God, and were joined by those of the other ships, with tears of joy and transports of congratulation. This office of gratitude to Heaven was followed by an act of justice to their commander. They threw themselves at the feet of Columbus, with feelings of self-condemnation mingled with reverence. They implored him to pardon their ignorance, incredulity, and insolence, which had created him so much unceasing disquiet and had so often obstructed the prosecution of his well-concerted plan; and, passing in the warmth of their admiration from one extreme to another, they now pronounced the man whom they had so lately reviled and threatened to be a person inspired by Heaven with sagacity and fortitude more than human, in order to accomplish a design so far beyond the ideas and conception of all former ages.”

Many excellent writers have described this wondrous incident, but none so well as the historian of America, Dr. Robertson, whose eloquent account is borrowed in the preceding lines. The great event occurred on Friday, the 12th of October, 1492, and the connection between the two worlds began. The place he first landed at was San Salvador, one of the Bahamas; and after attaching Cuba and Hispaniola to the Spanish crown, and going through imminent perils by land and sea, he achieved his glorious return to Palos on the 15th of March, 1493. He brought with him some of the natives of the different islands he had discovered, and their strange appearance and manners were vouchers for the facts he stated. The whole town, when he came into the harbour, was in an uproar of delight. “The bells were rung, the cannon fired, Columbus was received at landing with royal honours, and all the people, in solemn procession, accompanied him and his crew to the church, where they returned thanks to Heaven, which had so wonderfully conducted, and crowned with success, a voyage of greater length, and of more importance, than had been attempted in any former age.”[5]

SIXTEENTH CENTURY

Leonardo Da Vinci, Michael Angelo, Raffaelle, Correggio, Titian, (Painters,) Sir Philip Sydney, Raleigh, Spenser, Shakspeare, (1564-1616,) Ariosto, Tasso, Lope de Vega, Calderon, Cervantes, Scaliger, (1484-1558,) Copernicus, (1473-1543,) Knox, (1505-1572,) Calvin, (1509-1564,) Beza, (1519-1605,) Bellarmine, (1542-1621,) Tycho Brahe, (1546-1601.)

THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY

THE REFORMATION – THE JESUITS – POLICY OF ELIZABETHIn the last two years of the preceding century the course of maritime discovery had been accelerated by fresh success. To balance the glories of Columbus in the West, the “regions of the rising sun” had been explored by Vasco da Gama, a Portuguese. This great navigator sailed back into the harbour of Lisbon on the 16th of September, 1499, with the astonishing news that he had doubled the Cape of Storms, which had so alarmed Bartholomew Diaz, and established relations of amity and commerce with the vast continent of India, having traded with a civilized and industrious people at Calicut, a great city on the coast of Malabar. Under these reiterated widenings of men’s knowledge of the globe, the human mind itself expanded. Familiar names meet us from henceforth in the most distant quarters of the world. All national or domestic history becomes mixed up with elements hitherto unknown. The balance of power, which is the new constitution of the European States, depends on circumstances and places of the most heterogeneous character. A treaty between France and Spain, or between England and either, is regulated by events occurring on the Amazon or Ganges. The whole world gets more closely connected than ever it was before, and we can look back on the proceedings of previous ages as filling a very narrow theatre, and regulated by very contracted interests, when compared with the universal policies on which public affairs have now to rest. At first, however, the great results of these stupendous discoveries were naturally not observed. Contemporaries are justly accused of magnifying the small affairs of life of which they are witnesses; but this observation does not hold good with respect to the really momentous incidents of human history. A man who saw Columbus return from his voyage, or Guttenberg pulling at his press, could not rise to the contemplation of the prodigious consequences of these two events. He thought, perhaps, a quarrel between two neighbouring potentates, or a battle between France and Spain, the greatest incident of his time. His son forgot all about the quarrel; his grandson had no recollection of the battle; but widening in a still increasing circle, expanding into still more wonderful proportions, were the Discovery of America and the Art of Printing,—showing themselves in combinations of events and changes of circumstances where they were never expected to appear,—the one threatening to overthrow the freedom of every State in Europe by the supremacy of the Spanish crown, the other in reality preventing the chance of that consummation by raising up the indomitable spirit of spiritual liberty. For there now came to the aid of national independence the far more elevating feelings of religious emancipation. Protestantism was not limited in this century to denial of the spiritual authority of popes, but embodied itself also in resistance to the political ambition of kings. America might have enabled Charles the Fifth to conquer all Europe, if the Reformation had not strengthened men’s minds with a determination to stand up against oppression.

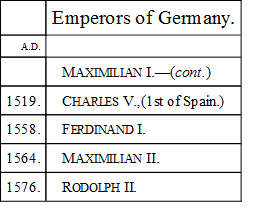

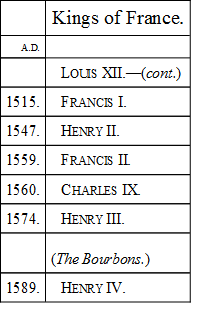

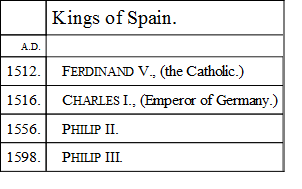

But the commencement of this century gave no intimation of its tempestuous course. The first few years saw the peaceable accession to the thrones of Spain and France and England of the three sovereigns whose contemporaneous reigns, and also whose personal characters, had the most preponderating influence on the succeeding current of events. We have left Spain for a long time out of these general views of a century’s condition and special notices of individual incidents which affected the condition of the world; for Spain for a long time lay obscurely between the ocean and the Pyrenees and carried on wars and policies which were limited by its territorial bounds. But, if we take a hurried retrospect of the last few years, we shall see that the different nations contained in the Peninsula had amalgamated into one mighty and strongly-cemented State. |A.D. 1497.|Ferdinand of Aragon, by marriage with Isabella of Castile, united the various nationalities under one homogeneous government, and by wisdom and magnanimity—the wisdom being the man’s and the magnanimity the woman’s—had rendered forever famous the joint reign of husband and wife, had reconciled the jarring factions of their respective subjects, and seen with the triumphant faith of believers and the satisfaction of sagacious rulers the reunion of the last Mohammedan State to the dominion of the Cross and of the crown. They watched the long, slow march of the Moorish king and his cavaliers as they took their way in poverty and despair from the towers and meadows of Granada, which a possession of seven hundred years had failed to make their own. This—the conquest of Granada—took place in 1491; and 1516 saw the supreme power over all united Spain descend on the head of the grandson of Ferdinand and Isabella,—inheriting, along with their royal dignity, the cautious wisdom of the one and the wider intelligence of the other. In three years from that time—it will be easy to remember that Charles’s age is the same as the century’s—he was elected to the Imperial crown, so that the greatest dominion ever held by one man since the days of Charlemagne now fell to the rule of a youth of nineteen years of age. Germany, the Netherlands, Naples, Sicily, and Spain, more than equalled the extent and power of Charlemagne’s empire. |A.D. 1520.|But ere Charles was a year older, vaster dominions than Charlemagne had ever dreamt of acknowledged his royal sway; for Montezuma, the Emperor of Mexico, whose realm was without appreciable limit either in size or wealth, professed himself the subject and servant of the Spanish king.

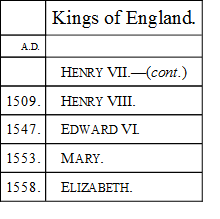

Henry the Eighth of England had also succeeded at an early age, being but eighteen in 1509, when the death of his father, the politic and successful founder of the Tudor dynasty, left him with a people silent if not quite satisfied, and an exchequer overflowing with what would now amount to ten or twelve millions of gold. This treasure had been accumulated by the infamous exactions of the late sovereign, who was aided in the ignoble service by two men of the names of Empson and Dudley. These were spies and informers, not, as in other climes and countries, about the religious or political sentiments of the people, but about their titles to their estates, the fines they were disposed to pay, or the bribes they would advance to the royal extortioner to avoid litigation and injustice. Henry had an admirable opportunity of showing his hatred of these practices, and availed himself of it at once. Before he had been four months on the throne, Empson and Dudley were ignominiously hanged; and with safe conscience, after this sacrifice at the shrine of legality, he entered into possession of the pilfered store. The people applauded the rapid decision of his character in both these instances, and scarcely grudged him the money when the subordinates were given up to their revenge. They could not, indeed, grudge their young king any thing; his manners were so open and sincere, his laugh so ready, and his teeth so white; for we are not to forget, in compliment to what is facetiously called the dignity of history, the immense advantages a ruler gains by the fact of being good-looking. Nobody feels inclined to find fault with a lad of eighteen, if moderately endowed with health and features; but when that lad is eminently handsome, rioting in strength and spirits, open in disposition, and, above all, a king, you need not wonder at the universal inclination to overlook his faults, to exaggerate his virtues, and even, after an interval of two hundred and fifty years, to hear the greatest tyrant of our history, and the worst man perhaps of his time, talked of by the ordinary title of Bluff King Hal. If he had been as ugly and hump-backed as his grand-uncle Richard the Third, he would have been detested from the first.

But in the neighbouring land of France there reigned at the same time a prince almost as handsome as Henry, and nearly as popular with his people, with as little real cause. In 1515, Francis the First was twenty years of age, a perfect specimen of manly strength,—accomplished in all knightly exercises,—generous and magnificent in his intercourse with his nobility,—and the greatest roué and debauchee in all the kingdom of France. Here, then, at the beginning of the age we have now to examine, were the three mightiest sovereigns of Europe, all arriving at their crowns before attaining their majority; and with so many years before them, and such powerful nations obeying their commands, great prospects for good or evil were opening on the world. But in the early years of the century no human eye perceived in what direction the future was going to pursue its course. People were all watching for the first indication of what was to come, and kept their eyes on the courts of Paris and London and Madrid; but nobody suspected that the real champions of the time were already marshalling their forces in far different situations. There was a thoughtful monk in a convent in Germany, and a Spanish soldier before the walls of Pampeluna. These were the true movers of men’s minds, of the great thoughts by which events are created; and their names were soon to sound louder than those of Henry or Charles or Francis; for one was Martin Luther, the hero of the Reformation, and the other was Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits. Take note of them here as mere accessories to the march of general history: we shall return to them again as characteristics of the century on which they placed their indelible mark. At this time, in the gay young days of the three crowned striplings, these future combatants are totally unknown. Brother Martin is singing charming hymns to the Virgin, in a voice which it was delightful to hear; and Don Ignacio is also singing to his guitar the praises of one of the beautiful maidens of his native land. Public opinion was still stagnant with regard to home-affairs, in spite of the efforts of the infant press. People, bowed down by the claims of implicit obedience exacted from them by the Church, accepted with wondering submission the pontificate of such an atrocious murderer as Alexander the Sixth; and some even ingeniously founded an argument of the divine institution of the Papacy upon its having survived the eleven years’ desecration of that monster of cruelty and unbelief. Yet now it happened by a strange coincidence that the chair of St. Peter was to be filled by a gayer and more accomplished ruler than any of the earthly thrones we have mentioned. In 1513, Leo the Tenth, the most celebrated of the family of the Medicis of Florence, put on the tiara at the age of thirty-six, a period of life which was considered as youthful for the father of Christendom as even the boyish years of the temporal kings. And Leo did not belie the promise of his juvenility. None of the dulness of age, or even the caution of maturity, was perceived in his public or private conduct. He was a patron of arts and sciences, and buffoonery, and infidelity; and it is curious to observe how the pretensions of Rome were more shaken by the frivolous magnificence of a good-hearted, graceful voluptuary than they had been by the crimes of his two immediate predecessors, the truculent Borgia and the warlike Julius the Second.