полная версия

полная версияThe Eighteen Christian Centuries

Now then that Pepin is king, let Luitprand, or any other potentate, beware how he does injury to the Pope of Rome. Twice the Frank armies are moved into Italy in defence of the Holy See; and at last the Exarchate is torn from the hands of its Lombard oppressor, and handed over in sovereignty to the Spiritual Power. Rome itself is declared at the same time the property of the Bishop, and free forever from the suzerainty of the Emperors of the East. No wonder the gratitude of the Popes has made them call the kings of France the eldest sons of the Church. Their donations raised the bishopric to the rank of a royal state; yet it has been remarked that the generosity of the French monarchs has always been limited to the gift of other people’s lands. They were extremely liberal in bestowing large tracts of country belonging to the Lombard kings or the Byzantine Cæsars; but they kept a very watchful eye on the possessions of pope and bishop within their own domain. They reserved to themselves the usufruct of vacant benefices, and the presentations to church and abbey. At almost all periods, indeed, of their history, they have seemed to retain a very clear remembrance of the position which they held towards the Papacy from the beginning, and, while encouraging its arrogance against other principalities and powers, have held a very contemptuous language towards it themselves.

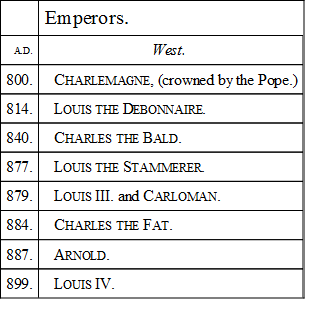

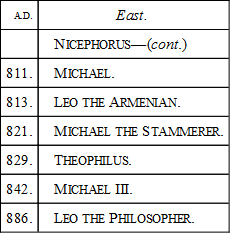

This, then, is the great characteristic of the present century, the restoration of the monarchical principle in the State, and its establishment in the Church. During all these wretched centuries, from the fall of the Roman Empire, the progress has been towards diffusion and separation. Kings rose up here and there, but their kingships were local, and, moreover, so recent, that they were little more than the first officer or representative of the warriors whose leaders they had been. A longing for some higher and remoter influence than this had taken possession of the chiefs of all the early invasions, and we have seen them (even while engaged in wresting whole districts from the sway of the old Roman Empire) accepting with gratitude the ensigns of Roman authority. We have seen Gothic kings glorying in the name of Senator, and Hunnish savages pacified and contented by the title of Prætor or Consul. The world had been accustomed to the oneness of Consular no less than Imperial Rome for more than a thousand years; for, however the parties might be divided at home, the great name of the Eternal City was the sole sound heard in foreign lands. The magic letters, the initials of the Senate and People, had been the ornament of their banners from the earliest times, and a division of power was an idea to which the minds of mankind found it difficult to become accustomed. It was better, therefore, to have only a fragment of this immemorial unity than the freshness of a new authority, however extensive or unquestionable. Vague traditions must have come down—magnified by distance and softened by regret—of the great days before the purple was torn in two by the transference of the seat of power to Constantinople. There were nearly five hundred years lying between the periods; and all the poetic spirits of the new populations had cast longing, lingering looks behind at the image of earthly supremacy presented to them by the existence of an acknowledged master of the world. A pedantic sophist, speaking Greek—the language of slaves and scholars—wearing the loftiest titles, and yet hemmed in within the narrow limits of a single district, assumed to be the representative of the universal “Lord of human kind,” and called himself Emperor of the East and West. The common sense of Goth and Saxon, of Frank and Lombard, rebelled against this claim, when they saw it urged by a person unable to support it by fleets and armies. When, in addition to this want of power, they perceived in this century a want of orthodox belief, or even what they considered an impious profanity, in the successor of Augustus and Constantine, they were still more disinclined to grant even a titular supremacy to the Byzantine ruler. Leo, at that time wearing the purple, and zealous for the purity of the faith, issued an order for the destruction of the marble representations of saints and martyrs which had been used in worship; and within the limits of his personal authority his mandate was obeyed. But when it reached the West, a furious opposition was made to his command. The Pope stood forward as champion of the religious veneration of “storied urn and animated bust.” The emperor was branded with the name of Iconoclast, or the Image-breaker, and the eloquence of all the monks in Europe was let loose upon the sacrilegious Cæsar. Interest, it is to be feared, added fresh energy to their conscientious denunciations, for the monks had attracted to themselves a complete monopoly of the manufacture of these aids to devotion—and obedience to Leo’s order would have impoverished the monasteries all over the land. A Western emperor, it was at once perceived, would not have been so blind to the uses of those holy sculptures, and soon an intense desire was manifested throughout the Western nations for an emperor of their own. Already they were in possession of a spiritual chief, who claimed the inheritance of the Prince of the Apostles, and looked down on the Patriarchs of Constantinople as bishops subordinate to his throne. Why should not they also have a temporal ruler who should renew the old glories of the vanished Empire, and exercise supremacy over all the governors of the earth? Why, indeed, should not the first of those authorities exert his more than human powers in the production of the other? He had converted a Mayor of the Palace into a King of the Franks. Could he not go a step further, and convert a King of the Franks into an Emperor of the West? With this hope, not yet perhaps expressed, but alive in the minds of Pepin and the prelates of France, no attempt was made to check the Roman pontiffs in the extravagance of their pretensions. Lords of wide domains, rich already in the possession of large tracts of country and wealthy establishments in other lands, they were raised above all competition in rank and influence with any other ecclesiastic; and relying on spiritual privileges, and their exemption from active enmity, they were more powerful than many of the greatest princes of the time. Everywhere the mystic dignity of their office was dwelt upon by their supporters. For a long time, as we have seen, their omnipotence was acknowledged by the two classes who saw in the use of that spiritual dominion a counterpoise to the worldly sceptres by which they were crushed. But now the worldly sceptres came to the support of the spiritual dominion. Its limit was enlarged, and made to include the regulation of all human affairs. |A.D. 768.|It was its office to subdue kings and bind nobles in links of iron; and when the son of Pepin, Charles, justly called the Great, though travestied by French vanity into the name of Charlemagne, sat on the throne of the Franks, and carried his arms and influence into the remotest States, it was felt that the hour and the man were come; and the Western Empire was formally renewed.

The curious thing is, that this longing for a restoration of the Roman Empire, and dwelling on its usefulness and grandeur, were dominant, and productive of great events, in populations which had no drop of Roman blood in their veins. The last emperor resident in Rome had never heard the names of the hordes of savages whose descendants had now seized the plains of France and Italy. Yet it seemed as if, with the territory of the Roman Empire, they had inherited its traditions and hopes. They might be Saxons, or Franks, or Burgundians, or Lombards, by national descent, but by residence they were Romans as compared with the Greeks in the East,—and by religion they were Romans as compared with the Sclaves and Saracens, who pressed on them on the North and South. It would not be difficult in this country to find the grandchildren of French refugees boasting with patriotic pride of the English triumphs at Cressy and Agincourt—or the sons of Scottish parents rejoicing in their ancestors’ victory under Cromwell at Dunbar; and here, in the eighth century, the descendants of Alaric and Clovis were patriotically loyal to the memory of the old Empire, and were reminded by the victories of Charlemagne of the trophies of Scipio and Marius. These victories, indeed, were not, as is so often found to be the case, the mere efforts of genius and ambition, with no higher object than to augment the conqueror’s power or reputation. They were systematically pursued with a view to an end. In one advancing tide, all things tended to the Imperial throne. Whatever nation felt the force of Charlemagne’s sword felt also a portion of its humiliation lightened when its submission was perceived to be only an advancement towards the restoration of the old dominion. It might have been degrading to acknowledge the superiority of the son of Pepin—but who could offer resistance to the successor of Augustus? So, after thirty years of uninterrupted war, with campaigns succeeding each in the most distant regions, and all crowned with conquest; after subduing the Saxons beyond the Weser, the Lombards as far as Treviso, the Arabs under the walls of Saragossa, the Bavarians in the neighbourhood of Augsburg, the Sclaves on the Elbe and Oder, the Huns and Avars on the Raab and Danube, and the Greeks themselves on the coast of Dalmatia; when he looked around and saw no rebellion against his authority, but throughout the greater part of his domains a willing submission to the centralizing power which rallied all Christian states for the defence of Christianity, and all civilized nations for the defence of civilization,—nothing more was required than the mere expression in definite words of the great thing that had already taken place, and Charlemagne, at the extreme end of this century, bent before the successor of St. Peter at Rome, and stood up crowned Emperor of the West, and champion and chief of Christendom.

|A.D. 786-814.|

The period of Charlemagne is a great date in history; for it is the legal and formal termination of an antiquated state of society. It was also the introduction to another, totally distinct from itself and from its predecessor. It was not barbarism; it was not feudalism; but it was the bridge which united the two. By barbarism is meant the uneasy state of governments and peoples, where the tribe still predominated over the nation; where the Frank or Lombard continued an encamped warrior, without reference to the soil; and where his patriotism consisted in fidelity to the traditions of his descent, and not to the greatness or independence of the land he occupied. In the reign of Charlemagne, the land of the Frank became practically, and even territorially, France; the district occupied by the Lombards became Lombardy. The feeling of property in the soil was added to the ties of race and kindred; and at the very time that all the nations of the Invasion yielded to the supremacy of one man as emperor, the different populations asserted their separate independence of each other, as distinct and self-sufficing kingdoms—kingdoms, that is to say, without the kings, but in all respects prepared for those individualized expressions of their national life. For though Charlemagne, seated in his great hall at Aix-la-Chapelle, gave laws to the whole of his vast domains, in each country he had assumed to himself nothing more than the monarchic power. To the whole empire he was emperor, but to each separate people, such as Franks and Lombards, he was simply king. Under him there were dukes, counts, viscounts, and other dignitaries, but each limited, in function and influence, to the territory to which he belonged. A French duke had no pre-eminence in Lombardy, and a Bavarian graf had no rank in Italy. Other machinery was at times employed by the central power, in the shape of temporary messengers, or even of emissaries with a longer tenure of office; but these persons were sent for some special purpose, and were more like commissioners appointed by the Crown, than possessors of authority inherent in themselves. The term of their ambassadorship expired, their salary, or the lands they had provisionally held in lieu of salary, reverted to the monarch, and they returned to court with no further pretension to power or influence than an ambassador in our days when he returns from the country to which he is accredited. But when the great local nobility found their authority indissolubly connected with their possessions, and that ducal or princely privileges were hereditary accompaniments of their lands, the foundations of modern feudalism were already laid, and the path to national kingship made easy and unavoidable. When Charlemagne’s empire broke into pieces at his death, we still find, in the next century, that each piece was a kingdom. Modern Europe took its rise from these fragmentary though complete portions; and whereas the breaking-up of the first empire left the world a prey to barbaric hordes, and desolation and misery spread over the fairest lands, the disruption of the latter empire of Charlemagne left Europe united as one whole against Saracen and savage, but separated in itself into many well-defined states, regulated in their intercourse by international law, and listening with the docility of children to the promises or threatenings of the Father of the Universal Church. For with the empire of Charlemagne the empire of the Papacy had grown. The temporal power was a collection of forces dependent on the life of one man; the spiritual power is a principle which is independent of individual aid. So over the fragments, as we have said, of the broken empire, rose higher than ever the unshaken majesty of Rome. Civil authority had shrunk up within local bounds; but the Papacy had expanded beyond the limits of time and space, and shook the dreadful keys and clenched the two-edged sword which typified its dominion over both earth and heaven.

NINTH CENTURY

John Scotus, (Erigena,) Hincmar, Heric, (preceded Des Cartes in philosophical investigation,) Macarius.

THE NINTH CENTURY

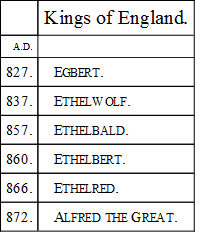

DISMEMBERMENT OF CHARLEMAGNE’S EMPIRE – DANISH INVASION OF ENGLAND – WEAKNESS OF FRANCE – REIGN OF ALFREDThe first year of this century found Charlemagne with the crown of the old Empire upon his head, and the most distant parts of the world filled with his reputation. As in the case of the first Napoleon, we find his antechambers crowded with the fallen rulers of the conquered territories, and even with sovereigns of neighbouring countries. Among others, two of our Anglo-Saxon princes found their way to the great man’s court at Aix-la-Chapelle. Eardulf of Northumberland pleaded his cause so well with Charlemagne and the Pope, that by their good offices he was restored to his states. But a greater man than Eardulf was also a visitor and careful student of the vanquisher and lawgiver of the Western world. Originally a Prince of Kent, he had been expelled by the superior power or arts of Beortrick, King of the West Saxons, and had betaken himself for protection, if not for restoration, to the most powerful ruler of the time. Whether Egbert joined in his expeditions or shared his councils, we do not know, but the history of the Anglo-Saxon monarchies at this date (800 to 830) shows us the exact counterpart, on our own island, of the actions of Charlemagne on the wider stage of continental Europe. Egbert, on the death of Beortrick, obtained possession of Wessex, and one by one the separate States of the British Heptarchy were subdued; some reduced to entire subjection, others only to subordinate rank and the payment of tribute, till, when all things were prepared for the change, Egbert proclaimed the unity of Southern Britain by assuming the title of Bretwalda, in the same way as his prototype had restored the unity of the empire by taking the dignity of Emperor. It is pleasant to pause over the period of Charlemagne’s reign, for it is an isthmus connecting two dark and unsatisfactory states of society,—a past of disunion, barbarity, and violence, and a future of ignorance, selfishness, and crime. The present was not, indeed, exempt from some or all of these characteristics. There must have been quarrellings and brutal animosities on the outskirts of his domain, where half-converted Franks carried fire and sword, in the name of religion, among the still heathen Saxons; there must have been insolence and cruelty among the bishops and priests, whose education, in the majority of instances, was limited to learning the services of the Church by heart. Many laymen, indeed, had seized on the temporalities of the sees; and, in return, many bishops had arrogated to themselves the warlike privileges and authority of the counts and viscounts. But within the radius of Charlemagne’s own influence, in his family apartments, or in the great Hall of Audience at Aix-la-Chapelle, the astonishing sight was presented of a man refreshing himself, after the fatigues of policy and war, by converting his house into a college for the advancement of learning and science. From all quarters came the scholars, and grammarians, and philosophers of the time. Chief of these was our countryman, the Anglo-Saxon monk Alcuin, and from what remains of his writings we can only regret that, in the infancy of that new civilization, his genius, which was undoubtedly great, was devoted to trifles of no real importance. Others came to fill up that noble company; and it is surely a great relief from the bloody records with which we have so long been familiar, to see Charlemagne at home, surrounded by sons and daughters, listening to readings and translations from Roman authors; entering himself into disquisitions on philosophy and antiquities, and acting as president of a select society of earnest searchers after information. To put his companions more at their ease, he hid the terrors of his crown under an assumed name, and only accepted so much of his royal state as his friends assigned to him by giving him the name of King David. The best versifier was known as Virgil. Alcuin himself was Horace; and Angelbert, who cultivated Greek, assumed the proud name of Homer. These literary discussions, however, would have had no better effect than refining the court, and making the days pass pleasantly; but Charlemagne’s object was higher and more liberal than this. Whatever monastery he founded or endowed was forced to maintain a school as part of its establishment. Alcuin was presented with the great Abbey of St. Martin of Tours, which possessed on its domain twenty thousand serfs, and therefore made him one of the richest land-owners in France. There, at full leisure from worldly cares, he composed a vast number of books, of very poor philosophy and very incorrect astronomy, and perhaps looked down from his lofty eminence of wealth and fame on the humble labours of young Eginhart, the secretary of Charlemagne, who has left us a Life of his master, infinitely more interesting and useful than all the dissertations of the sage. From this great Life we learn many delightful characteristics of the great man, his good-heartedness, his love of justice, and blind affection for his children. But it is with his public works, as acting on this century, that we have now to do. Throughout the whole extent of his empire he founded Academies, both for learning and for useful occupations. He encouraged the study and practice of agriculture and trade. The fine arts found him a munificent patron; and though the objects on which the artist’s skill was exercised were not more exalted than the carving of wooden tables, the moulding of metal cups, and the casting of bells, the circumstances of the time are to be taken into consideration, and these efforts may be found as advanced, for the ninth century, as the works of the sculptors and metallurgists of our own day. It is painful to observe that the practice of what is now called adulteration was not unknown at that early period. There was a monk of the name of Tancho, in the monastery of St. Gall, who produced the first bell. Its sound was so sweet and solemn, that it was at once adopted as an indispensable portion of the ornament of church and chapel, and soon after that, of the religious services themselves. Charlemagne, hearing it, and perhaps believing that an increased value in the metal would produce a richer tone, sent him a sufficient quantity of silver to form a second bell. The monk, tempted by the facility of turning the treasure to his own use, brought forward another specimen of his skill, but of a mixed and very inferior material. What the just and severe emperor might have done, on the discovery of the fraud, is not known; but the story ended tragically without the intervention of the legal sword. At the first swing of the clapper it broke the skull of the dishonest founder, who had apparently gone too near to witness the action of the tongue; and the bell was thenceforth looked on with veneration, as the discoverer and punisher of the unjust manufacturer.

The monks, indeed, seem to have been the most refractory of subjects, perhaps because they were already exempted from the ordinary punishments. In order to produce uniformity in the services and chants of the Church, the emperor sent to Rome for twelve monkish musicians, and distributed them in the twelve principal bishoprics of his dominions. The twelve musicians would not consent to be musical according to order, and made the confusion greater than ever, for each of them taught different tunes and a different method. The disappointed emperor could only complain to the Pope, and the Pope put the recusant psalmodists in prison. But it appears the fate of Charlemagne, as of all persons in advance of their age, to be worthy of congratulation only for his attempts. The success of many of his undertakings was not adequate to the pains bestowed upon them. He held many assemblages, both lay and ecclesiastical, during his lengthened reign; he published many excellent laws, which soon fell into disuse; he tried many reforms of churches and monasteries, which shared the same fortune; he held the Popes of Rome and the dignitaries of his empire in perfect submission, but professed so much respect for the office of Pontiff and Bishop, that, when his own overwhelming superiority was withdrawn, the Church rebelled against the State, and claimed dominion over it. His sense of justice, as well as the custom of the time, led him to divide his states among his sons, which not only insured enmity between them, but enfeebled the whole of Christendom. Clouds, indeed, began to gather over him some time before his reign was ended. One day he was at a city of Narbonese Gaul, looking out upon the Mediterranean Sea. He saw some vessels appear before the port. “These,” said the courtiers, “must be ships from the coast of Africa, Jewish merchantmen, or British traders.” But Charlemagne, who had leaned a long time against the wall of the room in a passion of tears, said, “No! these are not the ships of commerce; I know by their lightness of movement. They are the galleys of the Norsemen; and, though I know such miserable pirates can do me no harm, I cannot help weeping when I think of the miseries they will inflict on my descendants and the lands they shall rule.” A true speech, and just occasion for grief, for the descents of these Scandinavian rovers are the great characteristic of this century, by which a new power was introduced into Europe, and great changes took place in the career of France and England.

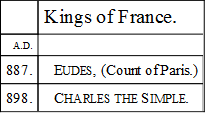

It would perhaps be more correct to say that, by this new mixture of race and language, France and England were called into existence. England, up to this date, had been a collection of contending states; France, a tributary portion of a great Germanic empire. Slowly stretching northward, the Roman language, modified, of course, by local pronunciation, had pushed its way among the original Franks. Latin had been for many years the language of Divine Service, and of history, and of law. All westward of the Rhine had yielded to those influences, and the old Teutonic tongue which Clovis had brought with him from Germany had long disappeared, from the Alps up to the Channel. |A.D. 814.|When the death of Charlemagne, in 814, had relaxed the hold which held all his subordinate states together, the diversity of the language of Frenchman and German pointed out, almost as clearly as geographical boundaries could have done, the limits of the respective nations. From henceforward, identity of speech was to be considered a more enduring bond of union than the mere inhabiting of the same soil. But other circumstances occurred to favour the idea of a separation into well-defined communities; and among these the principal was a very long experience of the disadvantages of an encumbered and too extensive empire. Even while the sword was held by the strong hand of Charlemagne, each portion of his dominions saw with dissatisfaction that it depended for its peace and prosperity on the peace and prosperity of all the rest, and yet in this peace and prosperity it had neither voice nor influence. The inhabitants of the banks of the Loire were, therefore, naturally discontented when they found their provisions enhanced in price, and their sons called to arms, on account of disturbances on the Elbe, or hostilities in the south of Italy. These evils of their position were further increased when, towards the end of Charlemagne’s reign, the outer circuit of enemies became more combined and powerful. In proportion as he had extended his dominion, he had come into contact with tribes and states with whom it was impossible to be on friendly terms. To the East, he touched upon the irreclaimable Sclaves and Avars—in the South, he came on the settlements of the Italian Greeks—in Spain, he rested upon the Saracens of Cordova. It was hard for the secure centre of the empire to be destroyed and ruined by the struggles of the frontier populations, with which it had no more sympathy in blood and language than with the people with whom they fought. Already, also, we have seen how local their government had become. They had their own dukes and counts, their own bishops and priests to refer to. The empire was, in fact, a name, and the land they inhabited the only reality with which they were concerned. We shall not be surprised, therefore, when we find that universal rebellion took place when Louis the Debonnaire, the just and saint-like successor of Charlemagne, endeavoured to carry on his father’s system. Even his reforms served only to show his own unselfishness, and to irritate the grasping and avaricious offenders whom it was his object to amend. Bishops were stripped of their lay lordships—prevented from wearing sword and arms, and even deprived of the military ornament of glittering spurs to their heels. The monks and nuns, who had almost universally fallen into evil courses, were forcibly reformed by the laws of a second St. Benedict, whose regulations were harsh towards the regular orders, but useless to the community at large—a sad contrast to the agricultural and manly exhortations of the first conventual legislator of that name. Nothing turned out well with this simplest and most generous of the Carlovingian kings. His virtues, inextricably interlaced as they were with the weaknesses of his character, were more injurious to himself and his kingdom than less amiable qualities would have been. Priest and noble were equally ignorant of the real characteristics of a Christian life. When he refunded the exactions of his father, and restored the conquests which he considered illegally acquired, the universal feeling of astonishment was only lost in the stronger sentiment of disdain. An excellent monk in a cell, or judge in a court of law, Louis the Debonnaire was the most unfit man of his time to keep discordant nationalities in awe. His children were as unnatural as those of Lear, whom he resembled in some other respects: for he found what little reverence waits upon a discrowned king; and personal indignities of the most degrading kind were heaped upon him by those whose duty it was to maintain and honour him. Superstition was set to work on his enfeebled mind, and twice he did public penance for crimes of which he was not guilty; and on the last occasion, stripped of his military baldric—the lowest indignity to which a Frankish monarch could be subjected—clothed in a hair shirt by the bands of an ungrateful bishop, he was led by his triumphant son, Lothaire, through the streets of Aix-la-Chapelle. |A.D. 833.|But natural feeling was not extinguished in the hearts of the staring populace. They saw in the meek emperor’s lowly behaviour, and patient endurance of pain and insult, an image of that other and holier King who carried his cross up the steeps of Jerusalem. They saw him denuded of the symbols of earthly power and of military rank, oppressed and wronged—and recognised in that down-trodden man a representation of themselves. This sentiment spread with the magic force of sympathy and remorse. All the world, we are told, left the unnatural son solitary and friendless in the very hour of his success; and Louis, too pure-minded himself to perceive that it was the virtue of his character which made him hated, persisted in pushing on his amendments as if he had the power to carry them into effect. He ordered all lands and other goods which the nobles had seized from the Church to be restored—a tenderness of conscience utterly inexplicable to the marauding baron, who had succeeded by open force, and in a fair field, in despoiling the marauding bishop of land and tower. It was arming his rival, he thought, with a two-edged sword, this silence as to the inroads of the churchman on the property of the nobles, and prevention of their just reprisals on the property of the prelate, by placing it under the safeguard of religion. The rugged warrior kept firm hold of the bishopric or abbey he had secured, and the belted bishop reimbursed himself by appropriating the wealth of his weaker neighbours.