полная версия

полная версияSunday-School Success

The voting in of new members, with the subsequent producing of the constitution for signatures, is a little ceremony as useful for the old scholars in reminding them of their class autonomy as it is inspiring to the new scholars. A hearty word of welcome from the teacher to the new-comers gives them a formal and public installation. They have indeed taken on themselves a new function.

The social committee will greatly add to the efficiency of any class. Monthly class socials are genuine means of grace. Our socials are thus managed: Each social has a solid backbone, consisting of a paper or talk by some member of the class, detailing little-known points in his own business. Of a neighboring class similarly organized, one is a young architect, another works in a rope-walk, a third holds an important position in a newspaper office, a fourth is in the leather business, the teacher of the class is a judge. Utilizing the experiences of their own members and friends, this class has held quite remarkable socials. It has found the contribution of the clerk in a furniture store as interesting as that of the young banker. The class have been wonderfully knit together by the bonds of a common and a widening interest. After these papers or talks (which are often appropriately illustrated), come discussion and questions, followed by games or light refreshments. By occasional joint socials of this kind we hope to draw together this class and my own. Of course, this is only one out of a myriad schemes of entertainment that could be devised for these class socials. The point the shrewd teacher will notice is that it is the scholars themselves who plan these socials, and who thus take into their own hands the creation of a warm, helpful class atmosphere. Every teacher should know that in making new scholars feel at home it is hardly his own sociability, but that of his scholars, that counts.

If the class is thus organized, the teacher must guard the authority of his class president as jealously as his own. If you want your class officers to feel genuine responsibility, it must be genuine responsibility that you put upon them. Give up to the president, during the conduct of business, your place in front of the class. Wait to be recognized by him before you speak. Make few motions. Inspire others to take the initiative.

The election of officers should come every six months, and it is best to bring about a thorough rotation in office. Improve every chance to emphasize the class organization. If your school arrangements permit, vote every month on the disposal of the class collections. If you must be absent a Sunday, ask the class to elect a substitute teacher, and ask the president to inform the substitute of his election. An alternate should be chosen also, to make the thing sure. This little device serves to make the scholars as loyal to the substitute teacher as to their own, for they have made him their own. In the course of the lessons, also, a wide-awake teacher will frequently mention and emphasize the class organization.

Of course the whole plan will fall flat if the teacher wholly delegates to his scholars any or all of these lines of work. He also must invite the strangers, if he expects his scholars to do so. He also must seek for new members, if he would inspire them to do the same. Without his sociableness they will soon become frigid. The teacher alone has the dipper of water that starts the pump. Any contrivance that lessens his responsibility lessens his success.

But the plan I have outlined has value, not because it permits the teacher to do less, but because it incites the scholars to do vastly more. An ounce drawn out is better than a ton put in. One thing you get them to do is a greater triumph than a dozen things you do much better for them.

Chapter XXX

Through Eye-Gate

Before his listless and restless audience the lecturer took in his hand a piece of chalk, turned to the blackboard, and touched it. Instantly he had the eager attention of all. He did nothing with the chalk; had not intended to do anything; he carried his point with it, nevertheless.

A teacher, plus a bit of chalk, is two teachers. And any one may double himself thus, if he choose to take a little pains.

Surely there need be no hesitation as to the materials. If you can have a blackboard, that is fine. I myself like best a board fastened to the wall, and a second board hinged to this after the fashion of a double slate. The outside may be used for "standing matter," and the inside opened up for the surprises.

But this is a great luxury. A portable, flexible blackboard will answer, if your class is away from the wall. You can roll it up and carry it home to practise there. You can use both sides of it. Such blackboards may be obtained now for two dollars.

Not even a flexible blackboard, however, is essential. A slate will serve you admirably, and some of the best chalk-talkers use simple sheets of manilla paper tacked to ordinary pine boards.

Then, as to the chalk, by all means use colored crayons. It is easy to learn effective contrasts of colors, and bright hues will increase many fold the attractiveness of your pictures and diagrams. But these crayons need not be of the square variety, sold especially for such work at thirty-five cents a box. They produce beautiful results, but the ordinary schoolroom box of assorted colors will serve your turn admirably and cost much less.

And if the materials are readily obtained, so is the artistic skill. Trust to the active imaginations of the children. Remember in their own drawings how vivid to them are the straight lines that stand for men, the squares that represent houses, the circles with three dots that set forth faces with eyes and mouth. I once saw Mrs. Crafts teach the parable of the Good Samaritan in a most fascinating way to some little tots, and her blackboard work was merely some rough ovals, each drawn half through its neighbor, to represent a chain of love,—love to papa, love to mamma, to sister, brother, friend, teacher,—neighbor. And as circle after circle was briskly added, every child was filled with delight. That same parable of the Good Samaritan I once saw perfectly illustrated—for all practical purposes—by four squares, each with two parallel lines curving from one upper corner to the opposite lower one, to represent the descent of the Jericho road, while the various scenes were depicted with the aid of short, straight lines, the man fallen among thieves being a horizontal line, the priest and Levite being stiffly upright and placed on appropriate points in the road, while the line for the Samaritan was leaning over as if helping his fallen brother rise! Surely that series of drawings was not beyond the artistic skill of any teacher.

One of the beauties of such simple work is that it may be dashed off in the presence of the scholars, while more elaborate pictures must be prepared beforehand; and half the value of blackboard work is in the attention excited by the moving chalk. I use the expression "dashed off," but I do not want to imply careless work. The straight lines should be as straight as you can make them without a ruler, the circles as true circles as can be drawn without a string, and the stars should have equal points. The simpler the drawing, the more need that every mark should have its mission and fulfill it well. A confused scrawl will only make mental confusion worse confounded. Don't be satisfied with rough work, or it will constantly become rougher. Try to do better all the time.

Of course, this means home practice, even for the simplest of exercises, like Mrs. Crafts' links of the love-chain. The nearer the links are to perfect ovals, the better. The more nicely they are shaded on one side, the more distinct will be the impression of a chain. And the more rapidly they can be drawn, the more tense will be the children's interest. A few easy lessons in drawing, from some public-school teacher or some text-book, will prove of inestimable value,—lessons enough to give you at least an idea of perspective, so that you can make a house or a box stand out from the board, and know which sides to shade of the inside of a door. Make such simple beginnings as I have indicated, and determine to advance, however slowly. It is hard to draw a man, but not so difficult if you are willing to begin with a little circle for the head, an oval for the body, and two straight lines for legs.

But even if you do not draw at all, it is well worth while to use chalk. Almost magical effects may be produced by a single sentence, sometimes a single word, written on the board. If your lesson is the last chapter of the Bible, the one word "Come!" will be blackboard work enough. Add to it, if you will, at the close of the recitation, this earnest question: "Why not to-day?" Every lesson has its key-word or its key-sentence. Write it large on your scholars' hearts by writing it large upon the blackboard.

In such work, as in drawing, you may begin with simple writing (your best script, however!) and go on to as high a degree of elaborateness as you fancy. A printer's book of samples will introduce you to fascinating and varied forms of letters. Your colored chalks may be used in exquisite illumination. You may learn from penmen their most bewitching scrolls. And all of this will be enjoyed by the children, and will contribute to the impressiveness of the truth, provided you are jealous to keep it subordinate to the truth. Otherwise, plain longhand is to be preferred to the end of the chapter.

Another easy way to use the blackboard—still without venturing on drawing—is by constructing diagrams. What a key to Scripture chronology, for instance, is furnished your scholars when you draw a horizontal line to represent the four thousand years from Adam to Christ, bisect it for Abraham, bisect the last half for Solomon, bisect the third quarter for Moses, and continue to bisect as long as a famous man stands at the bisecting-point! How it clears up the life of Christ to draw two circles, the inner one for Jerusalem, the outer for Nazareth, dividing them into thirty-three parts for the years of our Saviour's life, and running a curved line in and out according as his journeys took him to Nazareth and beyond its circle, or back to Jerusalem at the feast-times! Such circles will also serve to depict graphically Paul's missionary journeys, the outer circle representing Antioch. Any series of historical events may well be strung along a vertical line divided into decades, and parallel series, as in the history of the northern and southern kingdoms, along two parallel verticals. An outline map, such as the teacher may draw from memory, will furnish an excellent basis for another kind of diagram, the progress of persons or of series of events being traced from place to place by dotted lines, a different color for each person or journey or group of incidents.

Acrostics furnish still another use for the blackboard. For example, draw out from the class by questions a list of the prominent characteristics of David. He was

● Daring

● Active

● Vigilant

● Inspired

● Dutiful

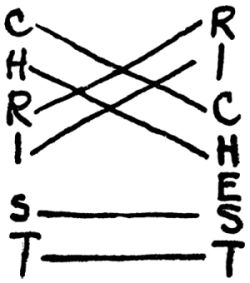

Not until the list is completed does the class see that its initial letters spell David's name. You have attained the element of surprise, so valuable in work of this sort. Again, in a lesson on the rich young man, or on Dives and Lazarus, or on Zaccheus, write in a vertical column the letters of Christ's name, and draw straight lines to the right in various directions, as shown in the following diagram. Transferring the letters, or getting some scholar to transfer them, to the points indicated, you quickly insert an E, and it reads: "Christ—richest."

The application is obvious, and will never be forgotten.

Often, in seeking for such an effective presentation of a lesson's truth, we hit upon alliteration, and then our blackboard work is easy. Three P's:

P P P

Fill them out, as the lesson proceeds, thus:

harisee ompously

P Prayed P

ublican enitently

And often, again, our form will be based upon similar terminations or beginnings of words, such as:

{ choosing

Solomon { reigning

{ sinning

Suggestions and examples of such work might be indefinitely multiplied. It is one of the easiest, yet one of the most effective, methods of fixing the points of a lesson.

The earnest teacher will be drawn irresistibly from the use of the chalk in diagrams, acrostics, and the like, to simple drawings; and by this time he will realize the importance of simplicity. A set of steps, for instance, is easy to draw; we may use only the profile; but the drawing will fix forever in your scholars' minds the events in Solomon's life. To a certain point the steps are all upward. Yellow chalk shows them to be golden. A word written over each step gives the event it symbolizes. On a sudden the steps turn downward, become a dirty brown, each representing a sin, and break short off as Solomon takes his terrible fall.

Who cannot draw a number of rough circles? They will stand for the stones thrown at Stephen. A word or initial written in each will represent the different kinds of persecutions that assail faithful Christians in our modern days. Who cannot draw a shepherd's crook, and write alongside it the points of the Twenty-third Psalm, or the ways in which Christ is the Good Shepherd? Who cannot draw a large wineglass, and write inside it some of the evils that come out of it? Who cannot draw a rectangle for a letter, and write upon it a direction, to make more vivid some of the epistles? or a trumpet inside seven circles, to brighten up the lesson on the fall of Jericho? As a rule, the very best chalk-talks are the simplest, and require the least skill in drawing.

But how to get the ideas? Where to find the pictures?

Of course, in the first place, from the books of first-rate chalk-talkers, such as Pierce's "Pictured Truth," Frank Beard's "The Blackboard in the Sunday-school," and Belsey's "The Bible and the Blackboard" (an English book). Of course, also, from the many admirable periodicals that publish blackboard hints, such as the "Lesson Illustrator," the "Sunday-school Times," and the teachers' magazines of the various denominations. Get hints also from the blackboard work of the public school and the kindergarten, as to manner, if not as to matter.

But as for the design, your own is the best for you, and not another's. Study all the blackboard work you can find, and retain whatever gravitates to you; but your own original design is the one you will best understand, and in presenting it you will have more of that enthusiasm which makes success.

Learn to find pictures all through the Bible. I have just been searching my mind for a Bible text that promised nothing in the way of a picture. At last I thought that "All have sinned and come short of the glory of God" would do. But in another second two pictures popped into my mind. I saw a river whose further bank was beautiful with flowers and trees, the paradise of "the glory of God," and across the river a bridge—lacking its final portion. I saw a ladder reaching up into some golden clouds back of which shone heaven, the city of "the glory of God"; but all the top rounds of the ladder were missing. Bridge and ladder had "come short." God's hand was needed, reaching across, reaching down, to help us over the sin-gap into "the glory of God." I do not believe it possible to find any Bible texts, still less any twelve consecutive verses of the Bible, that do not hide somewhere a capital picture.

Read your Bible pictorially. Make sketches everywhere upon the margin. For practice, often take some passage sure to come up in the International Lessons, such as Psalm 1, Isaiah 53, Proverbs 3, Matthew 5, Luke 2, John 14, Acts 9, Romans 12, 1 Corinthians 13, Hebrew 11, James 3. Delve into the passage, meditate long over it, and see how many pictures you can get out of it.

Of the greatest assistance will be a book,—indexed as to texts, and also as to subjects, such as "temperance," "missionary," "resurrection," "courage,"—in which you will preserve every drawing you make, and all the most suggestive blackboard hints you clip from the teachers' magazines, together with simple outlines of all sorts of common subjects. These last will be particularly useful. There will be a ladder, an anvil, a horse, a lily, a broom, a fountain,—anything likely to be of use for a symbol. You will clip these from advertisements, catalogues, the illustrated papers and magazines, and you will find your collection useful in many ways.

I have spoken as if the teacher should do all the blackboard work. On the contrary, he should do none that he can get his scholars to do for him. No matter if they do not do it as well as he. Get them to practise beforehand. Let them begin with only the simplest work; they will soon astonish you with their proficiency. And the class will take far more interest in a poor drawing by one of their own number than in a good drawing by you.

Yes, and even when you preside at the blackboard yourself, give the class pencils and paper occasionally, and let them copy what you draw. Their attention will be assuredly fixed, and an ineffaceable impression made on their memory. The drawings they complete, however crude, they will be glad to carry home to show their parents, and treasure as souvenirs of the lesson, or keep, if you choose, against the coming review day. If you use this method, you will soon come to cherish a deeper liking for that prime pedagogical virtue, simplicity.

For a final word: Take pains that your word-pictures keep pace with your chalk. Don't ask your class what you have drawn—that might lead to embarrassing results! Tell them. Put in all sorts of graphic little touches, even though you cannot draw a tenth of what you are talking about. The man on the Jericho road—how full of fear he was as he walked; how he whistled to keep up his courage; how one robber peeped from behind a rock, and another whispered, "He's coming!" how they sprang out, and he ran, and a third rascal sprang out in front and knocked him down; how he shouted, "Help! Thieves! Help!" and how only the echo answered him in that lonely place—all this must have happened many a time on that Jericho road, and you have a perfect right to stimulate with such natural and inevitable details the imagination of the children.

That is what they are for—both our word-picturing and our chalk-picturing: not to exhibit our nimbleness of wit or of finger, but to quicken the minds of the children,—that alone,—and make them more eager in the pursuit of truth.

Chapter XXXI

Foundation Work

The work of the primary department lies at the foundation of all Sunday-school work. This does not mean that there is no chance of a child's becoming a good Bible scholar and a noble Christian if he misses the primary training, but it does mean that without a flourishing primary department a school can scarcely be called successful, while with it half the success of the school is assured. The primary teacher molds the soft clay; her successor with the child must cut the hard marble.

Teaching that thus lies at the foundation must deal with fundamental matters, with the greatest lives of the Bible, the great outlines of history, the great essentials of doctrine, the root principles of morality. Details are to be filled in later. The danger is that the teacher will attempt to teach too much, will expect the little ones to know about Hagar when it is enough for them to know about Isaac; or about Jeremiah, when Daniel would be sufficient; or about the order in which Paul wrote his letters, when it might well suffice for them to know that Paul wrote them.

But though many questions are too hard to ask, no question is too easy, and no point is so simple that in these first days you may safely take it for granted. Laugh if you please, but I do not think that even these days of sand-maps and pricked cards have produced a method much more helpful for the primary teacher than the old questioning of my boyhood, over and over repeated: "Who was the first man?" "Who was the strongest man?" "Who was the oldest man?" and the like.

The primary teacher's right-hand man is named Drill,—Ernest Drill. No mnemonic help—that is a help—is to be despised. Rhymes giving in order the books of the Bible, the Commandments, Beatitudes, list of the twelve apostles, may wisely be used. No memory verse or golden text, once learned, should be allowed to lapse into that easy pit, a child's quick forgetfulness. Better one thing remembered than a hundred things forgotten. Foundation-stones are few and simple, but they must be firm.

Now the first essential, if one would do this foundation work successfully, is to get a room to work in. A room that lets in floods of sunshine and fresh air. A room with pretty pictures and bright mottoes on the wall, with canary songs and blooming plants. A room with little chairs, graded to the scholars' little heights. A room with a visitors' gallery for the mothers. Or, if your church was not blessed with a Sunday-school architect, then such a room in a house next door or across the street, to which your class may withdraw after the opening exercises. Or, if your work must be done in the church, as so much primary work must be, then a temporary room, shut off by drawn curtains, or even by a blackboard and a screen, is far better than the distractions of the open school.

The blackboard just mentioned, at any rate, the room should contain; the shrewd use of it will create an intense interest that will almost cause oblivion of the most distracting surroundings. A padded board gives the best effects,—such a board as you yourself may easily and cheaply make with a pine backing, a few layers of cheap soft cloth, and a covering of blackboard cloth nailed firmly over all. In the chapter on blackboard work I have tried to show how easily possible, and at the same time how valuable, is the use of the blackboard. If the children are too small to read, they may at least know their letters, and recognize S for Saul and P for Peter, and a cross for Christ, while the immense resources of simple drawings are always open to you.

The primary teacher is fortunate, nowadays, in being able to buy, at slight cost, series of pictures illustrating each quarter's lessons. These pictures are either colored brightly or simple black and white, and vary in size from four or five square feet to the little engravings in the Sunday-school paper. Whatever picture is used should be hidden until it is time to exhibit it, and produced with a pretty show of mystery and triumph. Some teachers hang these pictures, after use, in a "picture-gallery," where the children may become familiar with them, and to this gallery they may be sent for frequent reference against the coming review day.

After all, the primary teacher's chief reliance for purposes of illustration must be natural objects. In this reliance we merely imitate the example of the great Teacher. The objects to be used will most often be suggested by the lesson text itself. A lily, a vine, seed, leaven, a door, a sickle, a cake, a cup, grass,—are not each of these objects at once associated in your mind with passages of Scripture? Hunt out the suggested objects, and simply hold them before the children as you talk about the lesson, and you will find them a wonderful assistance.

A more difficult process is to discover illustrative objects when none are directly suggested in the text. In a temperance lesson, for instance, there may be no mention of the wine-cup, yet you will bring a glass, fill it with wine-colored water, and place in it slips of paper cut to resemble snakes. On each is written some fearful result of drinking alcoholic liquors; and after the children have drawn forth, with pincers, one after the other, and read what is written upon it, they will not soon forget how many evils come out of the wine-cup.

You may be talking about the imprisonment of John the Baptist. Produce a pasteboard chain, painted black on one side. Each link tells in red letters one of the horrors of his imprisonment,—loneliness, fear, despair, and the like. Turn over the chain and show the underside gilded, the links reading, "More faith," "Near to God," "God's favor," "Courage," "Eternal reward." There was a bright side, after all.