полная версия

полная версияFictitious & Symbolic Creatures in Art

The Sea-horse of the North, or walrus—the Rossmareus or Morse of the Scandinavians, the Trichecus rosmarus of science, is fifteen or twenty feet long, or even longer, and armed with huge canine teeth, sometimes measuring thirty inches in length—tusks which furnish no small amount of our commercial ivory. Many are the thrilling stories of the chase of these great sea-horses, for the walrus fights for his life as determinedly as any animal hunted by man. The walrus has had the honour assigned to it also of being the original of the mermaid, and Scoresby says the front part of the head of a young one without tusks might easily be taken at a little distance for a human face, especially as it has a habit of raising its head straight out of the water to look at passing ships.

The manatee, or sea-cow, found on the tropical coasts and streams of Africa and America, is called by the Portuguese and Spaniards the “woman-fish,” from its supposed close resemblance. Its English name comes from the flipper resembling a human hand—manus—with which it holds its young to its breast. One of this species, which died at the Royal Aquarium in 1878, was as unlike the typical mermaid as one could possibly imagine, giving one a very startling idea of the difference between romance and reality; but if it was observed in its native haunts, and seen at some little distance, and then only by glimpses, it might possibly, as some have asserted, present a very striking resemblance to the human form.

Sir James Emerson Tennent, speaking of the Dugong, an herbivorous cetacean, says its head has a rude approach to the human outline, and the mother while suckling her young holds it to her breast with one flipper, as a woman holds an infant in her arm; if disturbed she suddenly dives under water and throws up her fish-like tail. It is this creature, he says, which has probably given rise to the tales about mermaids.

Seals differ from all other animals in having the toes of the feet included almost to the end in a common integument, converting them into broad fins armed with strong non-retractile claws. Of the many varieties of the seal family, from Kamchatka comes the noisy “Sea-lion” (Otaria jubata), so called from his curious mane. In the same neighbourhood we get the “Sea-leopard” (Leptonyx weddellii), and the “Sea-bear” (the Etocephalus ursinus), whose larger and better-developed limbs enable him to stand and walk on shore. But the most important of the seals, in a commercial sense, are the “Harp Seal” (Phoca Grænlandica) and the Common Seal, or “Sea-dog” (Phoca vitulina), which yield the skins so valuable to the furrier. There are several other species, of which the most known are the Crested Seal, or Neistsersoak (Stemmatopus cristatus), and the Bearded Seal (Phoca barbata).

Apart from the seal having possibly given rise to legends of the mermaid, it has a distinguished position in superstition and mythology on its own account. In Shetland it is the “haff-fish,” or selkie, a fallen spirit. Evil is sure to follow the unfortunate destroyer of one of these creatures. In the Faroe Islands there is a superstition that the seals cast off their skins every ninth night and appear as mortals, dancing until daybreak on the sands. Sometimes they are induced to marry, but if ever they recover their skins they betake themselves again to the water.

Stephen of Byzantium relates that the ships of certain Greek colonists were on their expeditions followed by an immense number of seals, and it was probably on this account that the city they founded in Asia received the name of Phocea, from φώκη (Phoké), the Greek name of a seal, and they also adopted that animal as the type or badge of the city upon their coinage. The gold pieces of the Phoceans were well known among the Greek States, and are frequently referred to by ancient writers. “Thus from a single coin,” says Noel Humphreys,29 “we obtain the corroboration of the legend of the swarm of seals, of the remote epoch of the emigration in question, the coin being evidently of the earliest period, most probably of the middle of the seventh century before the Christian era.”

Luigi (+ 1598), brother to the Duke of Mantua, had for device a seal asleep upon a rock in a troubled sea, with the motto: “Sic quiesco” (“So rest I”). The seal, say the ancient writers, is never struck by lightning. The Emperor Augustus always wore a belt of seal-skin. “There is no living creature sleepeth more soundly,” says Pliny,30 “therefore when storms arise and the sea is rough the seal goes upon the rocks where it sleeps in safety unconscious of the storm.”

The poet Spenser embodies many of the conceptions of his time in the description of the crowning adventures of the Knight Guyon. He here refers to “great sea monsters of all ugly shapes and horrible aspects” “such as Dame Nature’s self might fear to see.”

“Spring-headed hydras, and sea-shouldering whales;Great whirlpools, which all fishes make to flee;Bright scolopendras arm’d with silver scales;Mighty monoceroses with unmeasured tails;The dreadful fish that hath deserved the nameOf death, and like him looks in dreadful hue;The grisly wasserman, that makes his gameThe flying ships with swiftness to pursue;The horrible sea-satyr that doth shewHis fearful face in time of greatest storm;Huge Ziffius, whom mariners eschewNo less than rocks, as travellers inform;And greedy rose-marines with visages deform;All these, and thousand thousand many moreAnd more deformed monsters, thousandfold.” Faerie Queen, Book ii. cant. xii.The early heralds took little account of these dreadful creatures—more easily imagined by fearful mariners or by poets than depicted by artists from their vague descriptions. The most imaginative of the tribe rarely ventured beyond such representations of marine monsters as appealed strongly and clearly to the universal sense of mankind—compounds of marine and land animals—either from a belief in the existence of such creatures, or because they used them as emblems or types of qualities, combining for this purpose the attributes of certain inhabitants of the sea with those of the land or of the air to form the appropriate symbol.

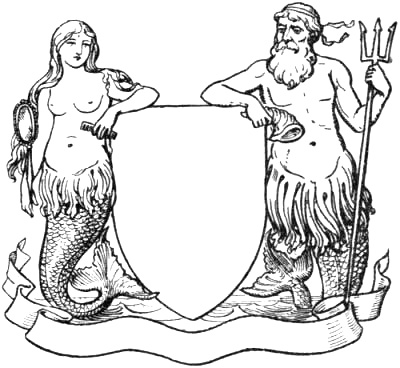

In modern heraldry such bearings are usually adopted with special allusion to actions performed at sea, or they have reference in some way to the name or designation of the bearer, and hence termed allusive or canting heraldry. Some maritime towns bear nautical devices of the fictitious kind referred to. For instance, the City of Liverpool has for supporters Neptune with his trident, and a Triton with his horn. Cambridge and Newcastle-on-Tyne have sea-horses for supporters to their city’s arms. Belfast has the sea-horse for sinister supporter and also for crest.

Many of the nobility also bear, either as arms or supporters, these mythical sea creatures, pointing in many instances to memorable events in their family history; indeed, as islanders and Britons, marine emblems—real and mythical—enter largely into our national heraldry.

Poseidon or Neptune

Poseidon or Neptune, the younger brother of Zeus (Jupiter), sometimes appears in heraldry, usually as a supporter. In the ancient mythology he was originally a mere symbol of the watery element, he afterwards became a distinct personality; the mighty ruler of the sea who with his powerful arms upholds and circumscribes the earth, violent and impetuous like the element he represents. When he strikes the sea with his trident, the symbol of his sovereignty, the waves rise with violence, as a word or look from him suffices to allay the fiercest tempest. Poseidon (Neptune) was naturally regarded as the chief patron and tutelary deity of the seafaring Greeks. To him they addressed their prayers before entering on a voyage, and to him they brought their offerings in gratitude for their safe return from the perils of the deep.

Dexter supporter of Baron Hawke.

In a famous episode of the “Faerie Queen” (Book iv. c. xi.) Spenser glowingly pictures the procession of all the water deities and their attendants:

“First came great Neptune with his three-forked mace,That rules the seas and makes them rise and fall;His dewy locks did drop with brine apaceUnder his diadem imperial:“And by his side his Queen with coronal,Fair Amphitrite, most divinely fair,Whose ivory shoulders weren covered all,As with a robe, with her own silver hair,And decked with pearls which the Indian seas for her prepare.”Amphitrite, his wife, one of the Nereids in ancient art, is represented as a slim and beautiful young woman, her hair falling loosely about her shoulders, and distinguished from all the other deities by the royal insignia. On ancient coins and gems she appears enthroned on the back of a mighty triton, or riding on a sea-horse, or dolphin.

Examples.—Baron Hawke bears for supporters to his shield an aggroupment of classic personations of a remarkable symbolic character, granted for the achievements of the renowned Admiral and Commander-in-Chief of the Fleet, Vice-Admiral of Great Britain, &c. &c., created Baron Hawke of Tarton, Yorks, 1776. The dexter supporter is a figure of Neptune, his mantle vert, edged argent, crowned with an eastern crown, or, his dexter arm erect and holding a trident pointing downwards in the act of striking, sable, headed silver, and resting his left foot on a dolphin proper.

Sir Isaac Heard, Somersetshire; Lancaster Herald, afterwards Garter. His arms, granted 1762, are thus blazoned in Burke’s “General Armory”: Argent a Neptune crowned with an eastern crown of gold, his trident sable headed or, issuing from a stormy ocean, the sinister hand grasping the head of a ship’s mast appearing above the waves, as part of a wreck, all proper; on a chief azure, the Arctic pole-star of the first between two water-bougets of the second.

Merman or Triton

“Triton, who boasts his high Neptunian raceSprung from the God by Salace’s embrace.”Camoëns, “Lusiad.”“Triton his trumpet shrill before them blewFor goodly triumph and great jollimentThat made the rocks to roar as they were rent.”Spenser, “Faerie Queen.” (Procession of the Sea Deities.)

Merman or Triton.

Triton, with two tails. German.

Triton was the only son of Neptune and Amphitrite. The poet Apollonius Rhodius describes him as having the upper parts of the body of a man, while the lower parts were those of a dolphin. Later poets and artists revelled in the conception of a whole race of similar tritons, who were regarded as a wanton, mischievous tribe, like the satyrs on land. Glaucus, another of the inferior deities, is represented as a triton, rough and shaggy in appearance, his body covered with mussels and seaweed; his hair and beard show that luxuriance which characterises sea-gods. Proteus, as shepherd of the seas, is usually distinguished with a crook. Triton, as herald of Neptune, is represented always holding, or blowing, his wreathed horn or conch shell. His mythical duties as attendant on the supreme sea-divinity would, as an emblem in heraldry, imply a similar duty or office in the bearer to a great naval hero.

Mermaid and Triton supporters.

Examples.—The City of Liverpool has for sinister supporter a Triton blowing a conch shell and holding a flag in his right hand.

Lord Lyttelton bears for supporters two Mermen proper, in their exterior hands a trident or.

Ottway, Bart.—Supporters on either side, a Triton blowing his shell proper, navally crowned or, across the shoulder a wreath of red coral, and holding in the exterior hand a trident, point downward.

Note.—In classic story, Triton and the Siren are distinct poetic creations, their vocation and attributes being altogether at variance—no relationship whatever existing between them. According to modern popular notions, however, the siren or mermaid, and triton, or merman as they sometimes term him, appear to be viewed as male and female of the same creature (in heraldic parlance baron and femme). They thus appear in companionship as supporters to the arms of Viscount Hood, and similarly in other achievements.

The Mermaid or Siren

“Mermaid shapes that still the waves with ecstasies of song.”T. Swan, “The World within the Ocean.”“And fair Ligea’s golden comb,Wherewith she sits on diamond rocks,Sleeking her soft alluring hair.”Milton, “Comus.”This fabulous creature of the sea, well known in ancient and modern times as the frequent theme of poets and the subject of numberless legends, has from a very early date been a favourite device. She is usually represented in heraldry as having the upper part the head and body of a beautiful young woman, holding a comb and glass in her hands, the lower part ending in a fish.

Ellis (Glasfryn, Merioneth).—Argent, a mermaid gules, crined or, holding a mirror in her right hand and a comb in her left, gold. Crest, a mermaid as in the arms. Motto, “Worth ein ffrwythau yn hadna byddir.” Another family of the same name, settled in Lancashire, bears the colours reversed, viz., gules, a mermaid argent.

Crest of Ellis.

Sir Josiah Mason.—Crest, a mermaid, per fess wavy argent and azure, the upper part guttée de larmes, in the dexter hand a comb, and in the sinister a mirror, frame and hair sable.

Balfour of Burleigh.—On a rock, a mermaid proper, holding in her dexter hand an otter’s head erased sable, and in the sinister a swan’s head, erased proper. The supporters of Baron Balfour are an otter and a swan, which will account for the heads appearing in the hands of the mermaid, instead of the traditionary comb and mirror. In some other instances the like occurs, as in the mermaid crest of Cussack, the mermaid sable crined or, holds in dexter hand a sword, and in the sinister a sceptre.

Sir George Francis Bonham, Bart.—Crest, a mermaid holding in dexter hand a wreath of coral, and in the sinister a mirror.

Wallop, Earl of Portsmouth, bears for crest a mermaid proper, with her usual accompaniments, the comb and mirror. Another family of the same name and bearing the same arms has for crest a mermaid with two tails extended proper, hair gold, holding her tails in her hands extended wide.

In foreign heraldry the mermaid is generally termed Mélusine, and represented with two fishy extremities.

Die Ritter, of Nuremberg.

Die Ritter of Nuremberg bears per fess sable and or, a mermaid holding her two tails, vested gules, crowned or.

The Austrian family of Estenberger bears for crest a mermaid without arms, and having wings.

A mermaid was the device of Sir William de Brivere, who died in 1226. It is the badge of the Berkeleys; in the monumental brass of Lord Berkeley, at Wolton-under-Edge, 1392 a.d., he bears a collar of mermaids over his camail. The Black Prince, in his will, mentions certain devices that he appears to have used as badges; among the rest we find “Mermaids of the Sea.” It was the dexter supporter in the coat-of-arms of Sir Walter Scott, and the crest of Lord Byron. The supporters of Viscount Boyne are mermaids. Skiffington, Viscount Marsereene, the Earl of Caledon, the Earl of Howth, Viscount Hood, and many other titled families bear it as crest or supporters. It is also borne by many untitled families.

The arms of the princely house of Lusignan, kings of Cyprus and Jerusalem, “Une sirène dans une cuvé,” were founded on a curious mediæval legend of a mermaid or siren, termed Mélusine, a fairy, condemned by some spell to become on one day of the week only, half woman, half serpent. The Knight Roimoudin de Forez, meeting her in the forest by chance, became enamoured and married her, and she became the mother of several children, but she carefully avoided seeing her husband on the day of her change; one day, however, his curiosity led him to watch her, which led to the spell being broken, and the soul with which by her union with a Christian she hoped to have been endowed, was lost to her for ever.

This interesting myth is fully examined in Baring Gould’s “Curious Myths of the Middle Ages.”

The mermaid is represented as the upper half of a beautiful maiden joined to the lower half of a fish, and usually holding a comb in the right hand and a mirror in the left; these articles of the toilet have reference to the old fable that always when observed by man mermaids are found to be resting upon the waves, combing out their long yellow hair, while admiring themselves in the glass: they are also accredited with wondrous vocal powers, to hear which was death to the listener. It was long believed such creatures really did exist, and had from time to time been seen and spoken with; many, we are told, have fatally listened to “the mermaid’s charmèd speech,” and have blindly followed the beguiling, deluding creature to her haunts beneath the wave, as did Sidratta, who, falling in the Ganges, became enamoured of one of these beautiful beings, the Upsaras, the swan-maidens of the Vedas.

All countries seem to have invented some fairy-like story of the waters. The Finnish Nakki play their silver harps o’ nights; the water imp or Nixey of Germany sings and dances on land with mortals, and the “Davy” (Deva), whose “locker” is at the bottom of the deep blue sea, are all poetical conceptions of the same description. The same may be said of the Merminne of the Netherlands, the White Lady of Scotland and the Silver Swan of the German legend, that drew the ship in which the Knight Lohengrin departed never to return.

In the “Bestiary” of Philip de Thaun he tells us that “Siren lives in the sea, it sings at the approach of a storm and weeps in fine weather; such is its nature: and it has the make of a woman down to the waist, and the feet of a falcon, and the tail of a fish. When it will divert itself, then it sings loud and clear; if then the steersman who navigates the sea hears it, he forgets his ship and immediately falls asleep.”

The legendary mermaid still retains her place in popular legends of our sea coasts, especially in the remoter parts of our islands. The stories of the Mirrow, or Irish fairy, hold a prominent place among Crofton Croker’s “Fairy Legends of the South of Ireland.” Round the shores of Lough Neagh old people still tell how, in the days of their youth, mermaids were supposed to reside in the water, and with what fear and trepidation they would, on their homeward way in the twilight, approach some lonely and sequestered spot on the shore, expecting every moment to be captured and carried off by the witching mere-maidens. On the Continent the same idea prevails. Among the numerous legends of the Rhine many have reference to the same fabled creature.

As we know, mariners in all ages have delighted in tales of the marvellous, and in less enlightened times than the present, they were not unlikely to have found many willing listeners and sound believers. Early voyagers tell wonderful stories of these “fish-women,” or “women-fish,” as they termed them. The ancient chronicles indeed teem with tales of the capture of “mermaids,” “mermen,” and similar strange creatures; stories which now only excite a smile from their utter absurdity. So late as 1857 there appeared an article in the Shipping Gazette, under intelligence of June 4, signed by some Scotch sailors, and describing an object seen off the North British coast “in the shape of a woman, with full breast, dark complexion, comely face” and the rest. It is probable that some variety of the seal family may be the prototype of this interesting myth.

The myth of the mermaid is, however, of far older date; Homer and later Greek and Roman poets have said and sung a great deal about it.

The Sirens of Classic Mythology

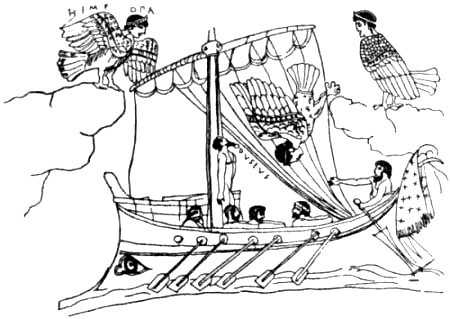

The Sirens (Greek, entanglers) enticed seamen by the sweetness of their song to such a degree that the listeners forgot everything and died of hunger. Their names were, Parthenope, Ligea, and Leucosia.

Ulysses and the Sirens. Flaxman’s “Odyssey.”

Parthenope, the ancient name of Neapolis (Naples) was derived from one of the sirens, whose tomb was shown in Strabo’s time. Poetic legend states that she threw herself into the sea out of love for Ulysses, and was cast up on the Bay of Naples.

The celebrated Parthenon at Athens, the beautiful temple of Pallas Athenæ, so richly adorned with sculptures, likewise derives its name from this source.

Dante interviews the siren in “Purgatorio,” xix. 7-33.

Flaxman, in his designs illustrating the “Odyssey,” represents the sirens as beautiful young women seated on the strand and singing.

Ulysses and the Sirens. From a painting on a Greek vase.

In the illustration from an ancient Greek vase gives a Grecian rendering of the story, and represents the Sirens as birds with heads of maidens.

The Sirens are best known from the story that Odysseus succeeded in passing them with his companions without being seduced by their song. He had the prudence to stop the ears of his companions with wax and to have himself bound to the mast. Only two are mentioned in Homer, but three or four are mentioned in later times and introduced into various legends. Demeter (Ceres) is said to have changed their bodies into those of birds, because they refused to go to the help of their companion, Persephone, when she was carried off by Pluto. “They are represented in Greek art like the harpies, as young women with the wings and feet of birds. Sometimes they appear altogether like birds, only with human faces; at other times with the bodies of women, in which case they generally hold instruments of music in their hands. As their songs are death to those subdued by them they are often depicted on tombs as spirits of death.”

By the fables of the Sirens is represented the ensnaring nature of vain and deceitful pleasures, which sing and soothe to sleep, and never fail to destroy those who succumb to their beguiling influence.

Spenser, in the “Faerie Queen,” describes a place “where many mermaids haunt, making false melodies,” by which the knight Guyon makes a somewhat “perilous passage.” There were five sisters that had been fair ladies, till too confident in their skill in music they had ventured to contend with the Muses, when they were transformed in their lower extremities to fish:

“But the upper half their hue retained still,And their sweet skill in wonted melody;Which ever after they abused to illTo allure weak travellers, whom gotten they did kill.”Book ii. cant. cxii.Shakespeare charmingly pictures Oberon in the moonlight, fascinated by the graceful form and the melodious strains of the mermaid half reclining on the back of the dolphin:

“Oberon: … Thou rememberestSince once I sat upon a promontory,And heard a mermaid on a dolphin’s backUttering such dulcet and harmonious breathThat the rude sea grew civil at her songAnd certain stars shot madly from their spheresTo hear the sea-maid’s music.”Commentators of Shakespeare find in this passage (and subsequent parts) certain references to Mary Queen of Scots, which they consider beyond dispute. She was frequently referred to in the poetry of the time under this title. She was married to the Dauphin (or Dolphin) of France. The rude sea means the Scotch rebels, and the shooting stars referred to were the Earls of Northumberland and Westmoreland, who, with others of lesser note, forgot their allegiance to Elizabeth out of love to Mary.