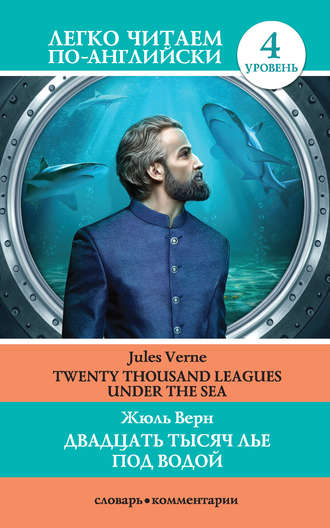

Двадцать тысяч лье под водой / Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea

Полная версия

Двадцать тысяч лье под водой / Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea

Жанр: книги о путешествияхзарубежная классикаизучение языкованглийский языклексический материалтекстовый материалфранцузская классикаUpper-Intermediate levelадаптированный английскийзнания и навыкиклассика жанраклассика приключенческой литературыкниги для чтения на английском языке

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2019

Добавлена:

Серия «Легко читаем по-английски»

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу