Полная версия

Solace of Lovers. Trost der Liebenden

The task of establishing a mint and defining the coinage standard was entrusted to Councillor Pechan. In Persia, the gold Toman is the coinage standard; its value is somewhat lower than that of the Austrian ducat (a thousand Tomans equals 3.3048 kilograms of fine gold, the Austrian ducat 3.4906 kilograms). The alloy for the Toman also contains silver (960 parts fine gold, 30 parts silver and 10 parts other metals). The Toman is soft, pliable, prone to wear and unedged. As a result, in view of the hereditary defect of all Orientals to remove metal from the coins, one rarely finds a full-weight coin, although they all have approximately the same weight, namely 34,425 grams, when they leave the mint. The governors of many cities, such as Qazvin, Rasht, Barfrouch, Isfahan, Shiraz, Kerman and Kermanshah, have the right to mint coins. There are many counterfeit coins in circulation, which makes it necessary to check each individual Toman for its weight and pliability or to hire the services of a money changer (Sarraf) for the purpose. The situation is not much better with the silver coin, the Qiran, which has the additional drawback of a variable fine silver content and therefore, also in view of the high price of gold, is only accepted for payment in small amounts.

These evils prompted the government to purchase minting machines in France and also to recruit a mint master there. Because of the difficulty of transporting the machinery, however, the heavy components were left unprotected on the shores of the Caspian Sea for a long time and only the lighter parts arrived in Tehran. The mint master therefore spent several idle years before he finally left the capital without fulfilling his mission. Councillor Pechan first made it his business to collect the disjecta membra. Two Austrian mechanics who happened to be passing through on their way to India were hired, the machines were cleaned and assembled, and finally a large building with a steam engine was constructed for the mint. The latest news is that a mint satisfying all the requirements will be established in a very short time. Only two obstacles still stand in the way: firstly, the need to define the coin standard, which causes a great many difficulties everywhere, and secondly, the shortage of the precious metal caused by the continuing silkworm disease, which means less gold is received in payment, while the country itself has no precious metal resources. At all events, Pechan has certainly achieved as much as can be achieved under the given circumstances.

In conclusion, I believe I am entitled to say that we Austrians have contributed our share to the knowledge of the country and the dissemination of culture in Persia. Every healthy idea cast on fertile ground sprouts and bears fruit, which multiplies from generation to generation. As it says in the Bible: “For just as the rain and snow come down from heaven, and do not return there without watering the earth.”

1 This lecture was given by Jakob Eduard Polak at the Oriental Museum in Vienna on 13 December 1876 and published in book form by Alfred Hölder in the same year. The text appears in this “Studioheft” with the kind permission of the Austrian National Library; it was produced using the digitised version available at http://digital.onb.ac.at/OnbViewer/viewer.faces?doc=ABO_%2BZ256627506 (date of access: 12.8.2020). The orthography of the original text has been modified by the editors.

2 In all countries where punishment is seen as retribution, as revenge on the model of an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth, there has to be room for the charitable institution of asylum. In Persia it takes various forms; for minor offences it is enough to enter the royal stable or to grip the cannons and so on, while for capital crimes there are specially designated sanctuaries, such as the temples of Shah Abdol Azim and Qom.

3 With the widespread sectarianism and secret societies of the Asians, including those of the Russians and Jews (sadikim), a relationship often develops between the teacher (murshid) and the students (murids), in which the former is regarded as a higher being, to whom blind obedience is owed and whose most insignificant items, such as saliva and rags of clothing, are kept as relics. Clear examples are provided by Murshid Shamil in the Caucasus and his warlike murids and the Old Man of the Mountain and the Assassins.

4 It may be of some interest to note that this was the first original work in Europe ever to be written and printed in Persian.

LIKE THE WIND IN THIS WORLD ...

Peter Leisch

“Where are we going?

Home, always home.”

Novalis (1772–1801)

TEHRAN

Shariati St. (opposite side of Arab Hosseini Blvd.), Molla Sadra St., Sharmad Dead End no. 11, fourth floor. When I wake up, I look through a large three-piece window topped by two rounded glass panes above into Tehran’s deep blue autumn sky. A crow croaks. From a distance the occasional sound of passing vehicles. A quiet quarter that falls almost silent in the evening, interrupted at times only by voices, slamming doors, sporadic noises and scraps of conversation from neighbouring buildings. On the windowsill a row of succulents and cacti, more potted plants on a wooden flower stand like a stool with long legs, a small palm tree beside the desk. On the wall hang Persian instruments, two baglamas, two Tanburs, a Kamancheh from Lorestan and a Setar. Amir’s music room, a small, intimate, light-filled room leading to a small south-facing balcony. From the fourth floor I have a good view of the quarter’s narrow alleys. When I stepped into the living room today my hosts had already gone to work, leaving the water for tea in the samovar simmering over the full flame of the gas stove. Basically very little has changed here. The scrap iron collector is still doing his rounds; the tinny sound of his constantly repeated calls reaches me from the loudspeaker mounted on the roof of his pickup. A dhikr, a prayer ritual of everyday life, which is part of the familiar soundscape of Persian cities, just like the smells of spices, wood, Sangak bread and uncertain origins, which all at once evoke so many memories in me. Sounds, scents, colours and long forgotten words in Farsi are raised from the depths of my forgetfulness so that I come to understand their meaning once more. Old faces, voices, stories of a hybrid dreamland, into which I can immerse myself again with a quite unexpected feeling of happiness, which everywhere else have long since faded beyond rescue.

“Just like the wind in this world – it blows and lifts the edge of the carpet,

and the rugs become restless and move. It whisks up waste and straws,

gives the surface of the pool the look of a coat of mail,

brings dance to trees, twigs and leaves, and extinguishes the lamps;

it brings a flare to the half-burned wood and a stir to the fire.

All these states seem diverse and different,

but from the standpoint of the object and the root and reality

they are but one as their movement comes from the wind.”

Molavi (1207–1273)

In the Tajrish Metro Station, the three extra-long, steeply rising escalators trigger a dizzying, surreal feeling of ascending into heaven: crowds of people floating upwards, all seemingly stiff as a poker. It reminds me of a scene in a science fiction film, the title of which escapes me. In the film, every human being is only allowed a certain amount of time to live, and when that time expires, an implanted crystal worn on the palm of the hand turns cloudy and dark. Then in a special, almost sacred ceremony, the candidates for death are “elevated” in a kind of coliseum; released from gravity, they float upwards into a cupola where – as if torched by a high voltage current – they are pulverised and fall away in a veritable shower of sparks.

Bombaste/Dead End, Tehran, 2019 / Bombaste/Dead End, Teheran, 2019

REND

In Persian the rend is an equivocal, ambiguous figure, for which there is no corresponding term in English. Hafez’ “Divan”, for example, includes the following passage: “If you want to visit me at my grave, you must be an impostor.” This suggests that the rend lives his life beyond the prevailing norms and obeys his own rules, which may well entail considerable risks – a free spirit, he operates between and often even against the conventions. The young Kurdish film artist Taher Saba strongly denies this interpretation; he sees the rend as someone “who is not sober, who finds the boundaries by pushing them back”. For Golzar the rend is someone who is neither clever nor wise, but both of these things at once. Afsoun says that Shams-e Tabrizi, Mowlana’s master and beloved soulmate, is a rend. “A kind of thief, but in a different, positive sense?” I ask. “Someone who has stolen Mowlana’s heart?” “Not just his heart,” Afsoun replies. It has to do with love. “A rend takes over your whole body, takes possession of you completely – in a way that is based on a higher respect.”

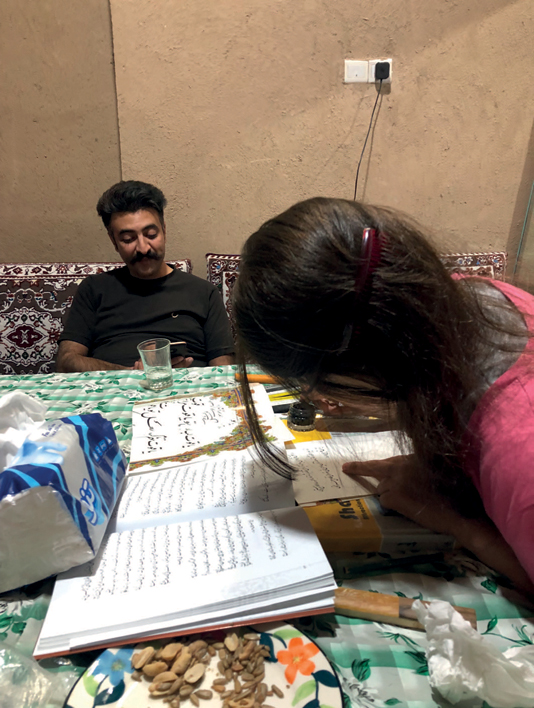

Calligraphy, Kharaqan/Semnan, November 2019 / Kalligrafie, Kharaqan/Semnan, November 2019

“The depth is outside. This can shake the foundations. Psychology, where are your terrors? The depth is outside. Only once we have devoured the entire contents of this esoteric bowl do we recognise the starting point of all art: drawing warmth from the object; recognising ourselves as a card dealt in a Tarock game of objects. With this, the by no means bottomless inner depth is exhausted. To the outside! Not as a completely incomprehensible process of letting it stand near; let it push in! Whether it is houses or stubborn opinions that seek to conceal their true origins – the eye sees, and at the same time it sees itself as part of the perceived image for the first time.”

Heimito von Doderer, Commentarii (1951–1956)

BASTAM/KHARAQAN

“Yek chand be koodaki be ostad shodim

Yek chand be ostadi e khod shad shodim

Payan e sokhan sheno ke ma ra che resid

Az khak bar amadim o bar bad shodim

Pour me a glass of red wine!

It will carry me there,

where I long to go –

even if only for less

than a moment.”

Omar Khayyam (1048–1131)

Roar of the oil-fired stove, outside our shoes on the icy concrete floor of the veranda, guarded by an old black-and-white watchdog that has curled up next to it. Quiet but constant scraping of Afsoun’s calligraphy reed pen as, in wide sweeping arcs, she bellies out the letters in a poem by Saadi. Ever since we left in the morning, she and Amir have been engaged in a poetic contest (Farsi: moshå éré). In a reciprocal poetic exchange, a poem is recited freely; the last letter of which must be the first letter of the following poem, which is the opponent’s response. Beginnings alternate with endings for hours, and the two pass on endings as new beginnings with playful ease. Hafez. Saadi. Mowlana. Khayyam. Bidel. Fazel Nazari. Arash Azarpek. Akhavan Sales. Forough Farrokhzad. Waw. Alif. Lam. Dal. Mim. Nun. Waw. One last word, always followed by another that is new. Mem. Re. Alif. Sefr. Hic. Alif.

ALAMUT

“We don’t master the ways, we are impostors,

we are not the game, we are the pack;

we are the brush in the painter’s hand,

we ourselves know not what we are.”

Molavi (1207–1273)

A light fall of wind-blown snow has set in; my gaze wanders over rocky ridges to small groups of poplars on the mountain slopes opposite, which are covered by patches of field. On the right the bluish-black rock face, partly overhanging, on whose narrow, elongated plateau Alamut is situated. Scree, sharp-edged fragments of stone and muddy, black earth; now and again, sparse vegetation consisting of thistles, mosses and a strange plant with thick, fleshy leaves. Several times on the way back, I start to pull off one of the leaves so that I can take it with me. But something makes me hesitate, holds me back. Is it this tenacious shape, which feels like a child’s clumsy hand, that makes it impossible for me to pull hard and pinch the leaf off with my fingernails? I have a strange feeling of wounding a living being. Would blood then flow from these strange leaves, whose shape reminds me of a tongue? I feel the same about the small shrubby willows, which are better protected with thorns. Here, too, I soon abandon what were never anything more than half-hearted attempts. The track ascends in a long arc. All is silence. A majestic calm that tolerates no interruption; even the minor gusts of wind that sweep across my face seem silent. The contours blur in the driving snow. Patches of mist and vague outlines. The world meanders and glows cold in all the slate-grey, snow-white colours of rock, leaden grounded nuances and watery highlights. In slow steps, groping carefully forward, I circle the black block of the fortress, which lingers constantly above my head. A dark ship, towering up into the grey snow cloudy sky. Then we reach the entrance, a wooden gate above which, in calligraphic ornamentation, a sign announces: “This is a house of God.”

KHORRAMABAD

“From your perspective, I’m mad,

from mine you are all sane.

So I pray that my madness increases

and your reason multiplies.

My madness comes from the power of love, your sound reason from the power of ignorance.”

Al-Shibli (8th cent. AD)

With tea and fresh dates, time passes unnoticed. At the same time, the continuous presence of a television, which, on countless channels and not unlike western media, delivers a galloping sequence of oriental imagery into my hosts’ living room. I see Turkish soaps with smart tough guys and blonde It girls, Kurdish pop channels with smiling PYD women’s battalions in combat training and fearless looking fighters with Kalashnikov rifles targeting an invisible enemy. And the stirring music that I had learned to love so much in Kermanshah. A deformed propaganda soundtrack of Middle Eastern killing fields, I now find it crude and oppressive, even in the knowledge that the Kurds are merely pawns to be sacrificed in a cynical proxy war, whose string-pullers are in turn manipulated by other puppet masters. Then, no less intolerable, advertising clips with a religious grounding from Saudi Arabia and the Emirates: a young man with black curls, rolling his eyes upward and reciting verses from the Quran to sugary synth-pop sounds and Café Mimi beats. White mountains of cloud pile up bombastically in time lapse, waterfalls plunge through jelly-green nature parks, pious hands open for prayer. Pilgrim masses move in an eerie, mesmerising circular motion around the Kaaba. An empty eye whose iris reflects a black cube. A maelstrom of millions upon millions of bodies around an impenetrable centre that startles me with an abrupt recognition of its significance – less from the everyday political context of the dissolution of old orders and borders, and more from the blatant exaggeration of religious symbolism I find revealed in these media spectacles. An obscene ride through hell that allows a vacuum, a non-place, a zombie spirituality of death to take shape, dissolving all signs of individual humanity until they disappear without a trace. The end of all stories. Chronicle of the void. Ashes of an extinguished fireplace in the icy glare of the screens. Only afterimage, empty gesture, parody. Cathode flicker. All trains terminate at the border. Ghabol nist.

How comforting it is when, later, I see an old man in a shabby suit passing by outside. He has his back turned to me and his hands clasped behind his back; gliding through his wrinkled hands are the clay beads of an old prayer chain.

ESFAHAN

“Afsus ke anche borde am bakhtanist

Beshnakhte ha tamam nashnakhtanist

Bardashte am har anche bayad bogzasht

Bogzashte am har anche bardashtanist

What misfortune that everything that befalls me

must be lost again.

Everything I thought I knew about my life

was not suitable to be taught.

I’m leaving everything behind that I should be taking on.

I accept everything that I should have left behind.”

Abu Said Abol Kheir (967–1049)

On Maydan-e Naqsh-e Jahan (Half of the World Square), the first thing you notice is a silence you would never expect in a square of this size in the middle of the city: you hear the quiet jingle of the horse-drawn carriages and see the spray of fountains raining on the surface of the pond in the middle of the square. Approaching the two-storey arcades of little shops and boutiques all around the square, you hear the gentle hammering of the coppersmiths. An atmosphere of timeless tranquillity and expansiveness makes this a place to pause, to let your gaze wander, to capture details, to savour the spaciousness and serene beauty of this architecture. None of what the traveller perceives is overbearing, shrill and obtrusive; one element combines naturally with the next to form an incomparably harmonious whole. Shah Abbas employed a succession of no fewer than five architects to create the square, one of whom made himself scarce after he had doubts about the feasibility of the structural design of the Great Mosque and the Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque. The two buildings were to support domes weighing about 60 and 30 tons respectively, and the architect’s courage failed him shortly after the foundations were laid. And yet: it all looks as if it were made in one piece; everything is consistent, nothing needs to be added; no lines, projections, extensions or superfluous decorations irritate the eye. Everything is balanced in sensitive and harmonious proportions, and even the position of the mosque at the southern end of the square, angled toward Mecca and gently retracted, forms a perfect conclusion.

Esfahan, Azadegan Teahouse, Chah Haj Mirza, 2017 / Esfahan, Azadegan Teehaus, Chah Haj Mirza, 2017

At the opposite end is the Qeysarriyeh Gate, the entrance to the Grand Bazaar, which meanders along as a dense labyrinth of twisting alleys, backyards, crossways, entrances and exits without any recognisable end. Moped riders suddenly emerge from crooked side alleys that open up to the outside, then weave their elastic way past passers-by, traders and loads transported on small handcarts, disappearing with a splutter behind lengths of fabric and wooden frames. On bales of cloth at the edge of the alley, an old man dozes under female mannequins dressed in chadors; in a tiny cage above a spice shop, a canary sings. The voices of the muezzins respond, starting up one after the other as they call to late afternoon prayer. A wave of smells from cook-shops, herbal scents and musty spice aromas, smoke from a charcoal fire, with a sooty teapot quietly simmering in the embers. With nowhere for tired feet to rest on the bumpy cobblestones, you balance between the flotsam of things that treacherously seek to block your path and unpredictable encounters from the half-light that make you miss your step. And yet it is a joyful stumbling, a stagger and forward swoop, which comes from a restlessness, a desire to reach and recognise the goal.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.