Полная версия

Face It

My mother colored her hair, so there was always peroxide in the bathroom. On my first attempt I didn’t get the mix right, so I ended up bright orange. I must have had at least a dozen different colors after that. I was also experimenting with makeup. I went through a beauty mark phase; I’d show up at school, my face looking like one of those connect-the-dots puzzles. My skills improved, but I still enjoyed experimenting.

At fourteen I was a majorette. I’d dress up in the tasseled boots, the tall hat, and the skirt that didn’t cover much at all, and I would march and twirl a baton. I was better at marching than baton twirling. I would always drop the baton, which meant I had to bend and pick it up, and which obviously added something extra to the performance.

I also joined a sorority, because that was what you were supposed to do, and it was the cool thing to do. These high school sororities and fraternities were curious groups—a sociologist or anthropologist would have a field day with them, I am sure. Each group had a strong identity and each was very competitive. But there were plenty of pluses too. When you’re a high school girl looking for an identity, a sorority gives you somewhere to belong. The girls ranged in age from freshmen to seniors and all called each other sister, so there was a lot of affection and camaraderie. The younger ones just needed to survive being pushed around on initiation night by their “sisters.”

Later on I quit. I don’t remember exactly how it went down, but I had some friends that they didn’t think were appropriate. I was offended by their telling me who I could and couldn’t have as friends and I left.

Though I wasn’t a troublemaker, I sometimes got detention—not for anything really bad, just cutting school. I’d go to Stewart’s Drive-In for a root beer and never come back. The worst thing about detention was having to sit there and write one stupid sentence over and over, thousands of times. I noticed that this one girl, K, would initial every page at the top with “JMJ.” When I asked why she did that, a little surprised at my ignorance, she let me know in no uncertain terms that the letters stood for “Jesus, Mary, and Joseph.”

K had been kicked out of Catholic school. So sitting next to her was the best thing about detention. She was a big, tough, gum-chewing Irish girl with sandy red hair and pimply teenage skin. She was always in detention for fighting. She had been labeled the town pump, the blow job queen, whether she deserved it or not. In small towns like ours, you could end up being caught forever in cruel traps. Small towns’ stigmata. However, K and I became friends. I was always interested in anyone who was so out front like that. I was fascinated by their danger. I wanted to be dangerous too but still wanted to protect myself. So I wasn’t dangerous—yet.

There was another friend whose mother was a nurse. One day she said she was going to Florida for a vacation. I said, “Gee, you’re so lucky!” I was dying to get out of this town and the idea of going to Florida for a vacation was very exotic—especially since I was born in Florida and had never been there since. But she actually went to Puerto Rico for an abortion. When she came back I looked at her and said, “My God, you don’t have a tan.” She just glared at me. I didn’t know that she had gotten knocked up. No one said anything.

I had a lot of boyfriends, usually one at a time, because that was the way it was done in this kind of small, uptight little town where reputations were made and lost in seconds. I would see one boy for a month or two and then I would see someone else. I really loved sex. I think I might have been oversexed, but I didn’t have a problem with that; I felt it was totally natural. But in my town in those days, sexual energy was very repressed, or at least clandestine. The expectation for a girl was that you would date, get engaged, remain a virgin, marry, and have children. The idea of being tied to that kind of traditional suburban life terrified me.

Some nights I would get a ride with a girlfriend and we would go to Totowa borough next to Paterson where my grandparents lived. Totowa had a notorious reputation back then and its main street was sometimes referred to as “Cunt Mile.” It was the thoroughfare where a lot of kids hung out. All the girls would walk around looking as hot and trashy as possible and the guys cruised the street looking at the girls. I would find a guy I liked and make out with him. They had great dances up there too. The town I came from was all white kids, but at these dances there was a really integrated crowd. And the music was just great because they played a lot of hot black music and everyone danced their ass off. I loved dancing. Still do.

For a while now, I had taken to going to New York; the bus fare was less than a dollar then. My favorite place to wander was Greenwich Village. I’d get in around ten in the morning, when all the bohemians and beatniks were still sleeping and everything was closed. I would just walk around, not looking for anything in particular, looking for everything really, and ingesting and digesting it all. Art, music, theater, poetry, and the sense that everything was up for grabs, you just had to see what fit. I was desperate to live in New York and be an artist. I could not wait for high school to end.

Well, finally it did end, in the summer of ’63. They held the graduation ceremony outside on the football field in the back of the high school. It was boiling hot that day, ridiculously hot, and I was melting in my cap and gown. I guess I felt off balance all through high school, so it seemed appropriate for the graduation ceremony to end this way.

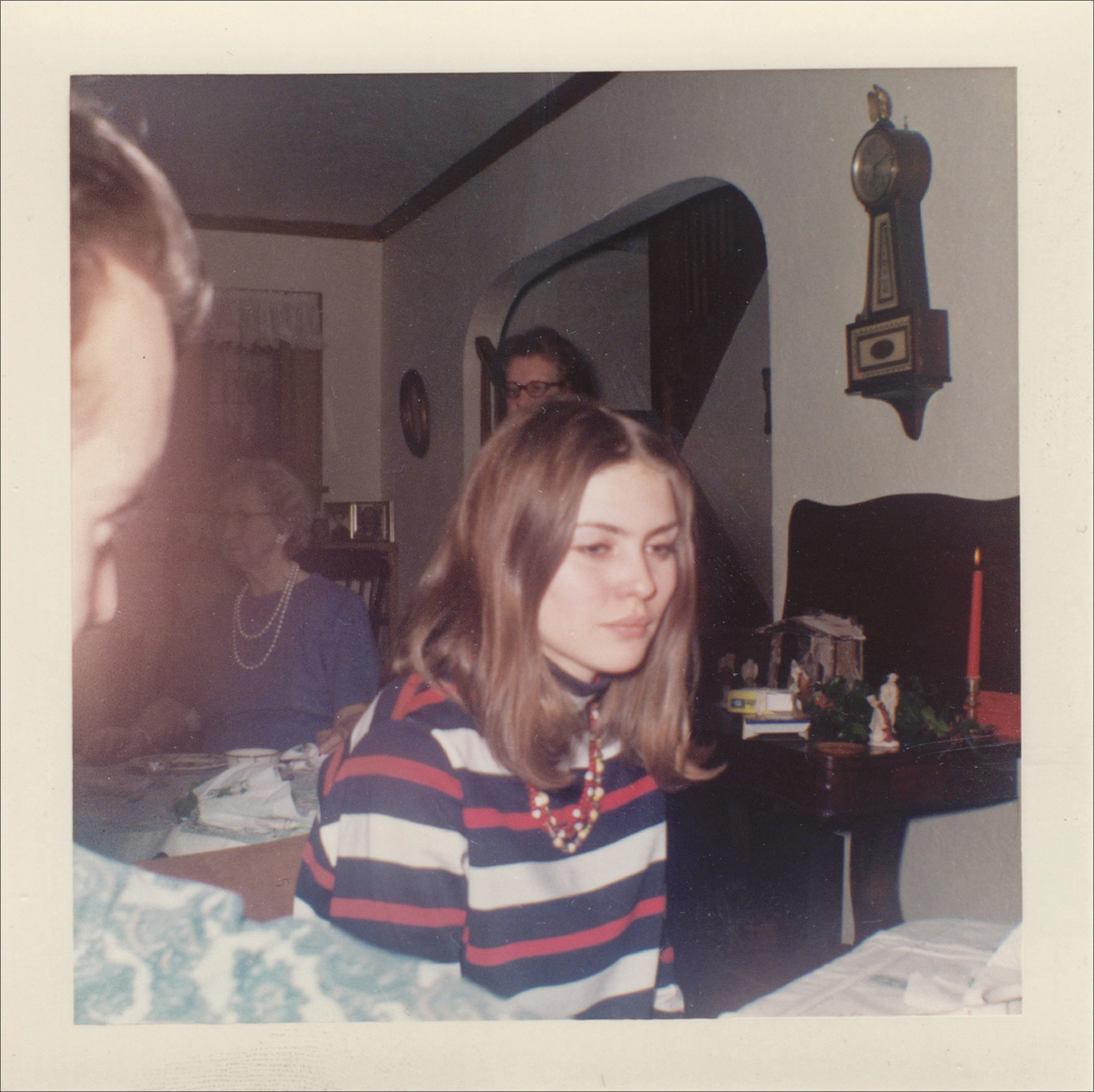

Family. Christmas.

Childhood and family photos, courtesy of the Harry family

So, this is where I pack my suitcase, wave goodbye to the folks, get on the bus, and watch through the window as New Jersey fades into the distance and the New York City skyscape looms? Well, actually no. I went to a junior college.

Centenary College in Hackettstown, New Jersey, was a women’s Methodist school run by some very old Southern ladies. Essentially, it was a finishing program to groom you for a respectable married life. I once referred to it as a “reform school for debutantes” and that’s really what it was to me—only I was no debutante and I did not want reforming. My reformation would be much, much different.

It was always planned that I would go to school. I told my parents that I wanted to go to an art school, preferably the Rhode Island School of Design—but it was a four-year program and it was beyond the budget. So, going to a two-year college was a compromise with my family, and that meant Centenary.

I wasn’t sure at all that I wanted to go to college. I just wanted to get out in the world and be an artist. I think my mother wanted me to go there because she felt that, since I was so shy, I wouldn’t do well anywhere else, and if I got homesick, it was only an hour and a half from home. So, in the fall I left for Hackettstown. I moved into a dorm, where I shared a room the first year with a girl named Jan and later with Karen—when they switched with each other. The second year, I roomed with a very smart, sweet girl named Carol Boblitz.

Now, the college did have a few good professors. Dr. Terry Smith taught American literature, which I absolutely loved—I loved Mark Twain and Emily Dickinson. And I liked the art teachers, Nicholas Orsini and his wife, Claudia. I was doing some painting and drawing while I was there. It wasn’t the kind of school where you had to work too hard. You could take very easy courses if you wanted and you would still be going to all the social events at other colleges, which was basically a dating service.

In my second year I went out with a guy called Kenny Winarick. His grandfather built the enormous Concord Resort Hotel in the Borscht Belt in the Catskills. They had first-rate entertainment—Judy Garland, Barbra Streisand—and lots of Jewish families would go. One day Kenny asked me, “Do you want to go to the mountains?” which is what they called the Catskills, but I was so naive I thought we were going hiking. He took me to this magnificent hotel, where everyone was dressed to the nines and I was in funky jeans and trying to be cool.

After we had gone out for a while, Kenny brought me to visit his mother at her place in New York. As I stood gazing out from the terrace of her wonderful apartment, my dreams of big-city living took further flight. It was just right. Just perfectly right. The spacious rooms weren’t overdecorated or too, too proper. A real environment where real people lived. People who loved being New Yorkers. Her prewar apartment building was named the Eldorado, at 300 Central Park West.

At the time, this mythological reference meant practically nothing to me, except that it was beautiful and exciting and something out of my wildest dreams. It was too soon for me to be drawing parallels between my own quest for an identity and the conquistadors’ quest for their fabled city of gold. But looking back, it was an ideal parallel to my entering the allure of New York through the gilded portals of the Eldorado. It was my personal sixties happening, as I joined the growing band of latter-day conquistadors searching for special treasure in the new city of beckoning promise.

All this sounds quite serious. And in a way it was. I was intense and determined but also floating in an often-turbulent sea of mixed emotions. I don’t think I was bipolar or depressed or schizophrenic or any such thing. I think I was normal enough, but in a time of expanded consciousness we were looking at the world in new and different ways.

Then there was also the psychedelic experience. Kenny’s mother, Gladys, was a psychoanalyst. She had a strength and curiosity and vitality that I absolutely loved. Her kids had an assurance and sense of humor about themselves that was way ahead of most of the people back home. Simply put, it was sophistication. As an analyst, Gladys was in on the latest lectures and symposiums and talks related to her field. So, she got an invitation for a session with Timothy Leary. She couldn’t go to this one, so Kenny and I went in her place. I think Leary may still have been teaching at Harvard or was about to be fired—and Alan Watts was there too. Leary’s book The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead had recently been published and I guess the idea behind these simulated “experiences” was to further legitimize their passion for LSD and its therapeutic potential.

The day came for our “trip” and we went to one of the most beautiful town houses I’d ever seen. It was on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, between Madison and Fifth Avenues. A truly elegant building with a carved entry and wrought iron railings with a barred doorway. We were led to a ground-floor room, where a small circle of people were sitting on the carpet. Leary was explaining the chakras and the stages of the experiment and encouraged us to relax and go with it. There were no drugs, no drinks, no food, only suggestions and directions about what this LSD trip could be like. In fact, it was based on a spiritual journey through different states of consciousness, known as the bardo.

At this time, Leary’s ideas were breathtakingly new and he had gotten some really dicey press about his teachings and drug use. We sat in the circle with the others and listened to Timothy chanting and speaking, guiding us through what might have been a mind expansion—if we could let ourselves go with it. Well, Kenny and I both were curious and wanted to learn something, so we hung in with the lecture. It went on forever and I was hoping there would be a snack at some point, but no such luck. We sat there for hours while Professor Leary and Alan Watts spoke about these levels of the mind. Finally we were all asked to interview each other.

There were all kinds of people there that day, not just hipsters or students. All kinds of businessmen and women; doctors, local and foreign; some nicely dressed uptown types; a few art-world people from the neighborhood; and analysts, of course. There was one man who made me nervous because he just radiated resistance. He held himself apart as if simply observing. He wore a white business shirt and dark gray trousers. He was balding and clean-cut. Of course, I was put opposite him for the interviews—the “getting to know you” part of the afternoon. I was uptight, not nice at all, and starving by then. So, I had it in for this poor man from the get-go and quizzed him in a way that he wasn’t expecting. It turned out he was there in some official capacity from either the CIA or the FBI. Which came as a jolt to Leary . . .

Kenny’s father was interesting too. He had a company called Dura-Gloss that made nail polish. A brand that my mother used. I used to love the little bottles it came in. It seemed a bit synchronistic that I should be seeing this guy. My mother must have thought so too, because she was putting the screws on Kenny to get serious. I thought he was great, but I wanted to experience what the world was and find out who I was before settling down. I think he did too. He went on to get his master’s degree and in a way I did too, eventually.

Me, I graduated with an associate of arts degree. I found a job in New York, but I couldn’t live there, I had no money, so I commuted back and forth, which I hated. I spent hours looking for an apartment in the city, but I couldn’t find anything remotely affordable. I guess I was moaning about it to my boss Maria Keffore at work. Maria, who was a very pretty Ukrainian woman, said, “Oh, you don’t have to worry. Come see my apartment. The rent is only seventy dollars a month.” OH MY GOD, how can it be so cheap, I thought, what must it be like? Well, it was fantastic. It was on the Lower East Side, which was a Ukrainian and Italian neighborhood at that time, and under rent control.

With Maria’s help I found an apartment with four rooms for just $67 on St. Mark’s Place. That first night in my new home, lying on the bed listening to the sounds of the street floating through my window, I felt like I was finally, twenty years into my life, in the place where my next life would begin.

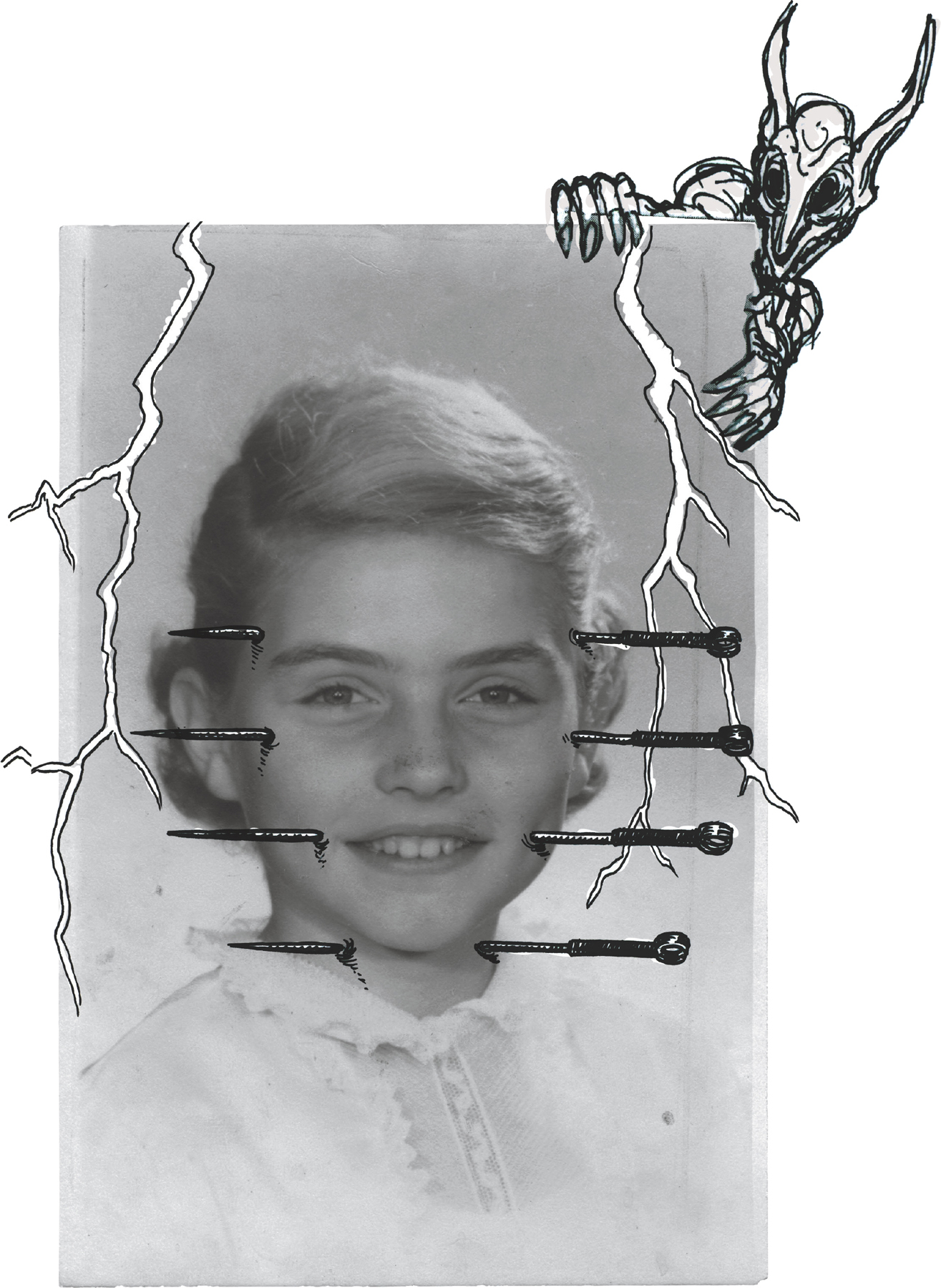

They used to say I looked European.

Childhood and family photos, courtesy of the Harry family

Sean Pryor

3

Click Click

Dennis McGuire

I hated my looks as a kid but couldn’t stop staring. Maybe there were one or two pictures that I liked, but that’s all. For me, capturing those looks on film was a horrible experience. Eventually the peeping, secretive, naughty aspect of it made being photographed all right, but voyeurism was not part of my vocabulary as yet. How could I know then that this face would help make Blondie into a highly recognizable rock band?

Does a photograph steal your soul? Were the aboriginal people right? Are photographs part of some mystical image bank, a type of visual Akashic record? A source of forensic evidence to examine the hidden, darker secrets of our souls, perhaps? Now, I can tell you that I’ve had my picture taken thousands of times. That’s a lot of theft and a lot of forensics. Sometimes I read things into those pictures that no one else seems to see. Just a tiny glimpse of my soul maybe, a passing reflection on a piece of glass . . . If you were me, by now you might be wondering if you had any soul left at all. Well, I had one of those Kirlian photographs taken once at a new age fair—and there supposedly was my soul, my aura, staring back at me. Yes, maybe there is still some of my soul to go around.

I was working in an almost soulless place: a wholesale housewares market at 225 Fifth Avenue, a huge building full of everything you can think of that had to do with housewares. My job was selling candles and mugs to buyers from the boutiques and department stores. This had not been part of the dream. I started thinking that since I was pretty—well, my high school yearbook had named me Best-Looking Girl—maybe I could get some modeling work. I’d met two photographers, Paul Weller and Steve Schlesinger, who did catalog work and paperback book covers, and I decided I would make a portfolio. My modeling book had shots running from hairstyles to yogic poses in a black leotard. What was I thinking? What kind of jobs could I possibly get with these weird photographs? Answer: one and done.

Then I saw a blind ad in the New York Times looking for a secretary. It turned out to be for the British Broadcasting Corporation. This was my first link to what would become a long, lovely relationship with Great Britain. They gave me the job on the strength of the sensational letter that my uncle helped me write. Once they had me, they realized that I wasn’t very good at what I was supposed to do, but they kept me anyway and I grew into the job. I learned to operate a telex machine. I also met some interesting people—Alistair Cooke, Malcolm Muggeridge, Susannah York—who came into the office/studio for radio interviews.

Plus, I met Muhammad Ali. Well, not exactly met him. “Cassius Clay is coming in to do a TV interview,” they said, so I snuck around the corner and wow, I saw this big, beautiful man walk into the TV studio and close the door. It was a soundproofed room with a small window way up high, so I decided, being athletic, that I was going to grab the windowsill and pull myself up and watch the taping. But, as I pulled myself up, my feet kicked the wall with a thud. In a flash, Ali’s head whipped round and he stared right at me. He nailed me and I was transfixed. He’d responded with the animal instinct and lightning reflexes of the supreme champion he was . . . I quickly dropped down to the floor, shocked and excited by the primal exchange. I could have gotten into trouble, particularly if they had already started to record, but fortunately no one else in the room had even noticed.

The offices for the BBC New York were in the International Building at Rockefeller Center, directly across from the monumental St. Patrick’s Cathedral. When I was working at the BBC, I believe Fifth Avenue was a two-way street, and the traffic was immense. A block south of the cathedral was Saks Fifth Avenue. In front of the International Building was and still is the enormous bronze statue of Atlas holding up the world. Behind it is Rockefeller Plaza, where the skating rink and the big Christmas tree are located during the holidays. During the summer the rink becomes an outdoor café. Directly behind the rink is the NBC building, with the Warner Bros. offices nearby too.

Strolling past the store windows and through the canyons of buildings was always interesting, and I made it a point to go over to visit one of my favorite characters, “Moondog.” This tall, bearded old man with his horned Viking helmet was a vision. He stood on the corner of Sixth Avenue and Fifty-Third in his long reddish cape holding his spearlike pole, selling booklets of his poetry. Moondog now has his own Wikipedia page, but back then few people who walked past him knew who the fuck he was. Most people steered clear of or didn’t even notice him—just another crazy “weirdo” to avoid or blank out.

Some thought he was an eccentric, blind, homeless man, but he was much more. Moondog was also a musician. He had an apartment uptown but kept his image and his privacy closely guarded. He designed instruments and also recorded, and he became adored by most New Yorkers. A beloved fixture, a true New York character who sometimes recited his poems to the businessmen and tourists hurrying past him. He was freaky but he was fondly called the Viking guy—even if no one knew about all his artistic achievements.

And then there were the more sinister types: the silent men in black selling small newspapers or booklets. They were serious, intense, kind of scary, which made them all the more intriguing, of course. They called themselves “the Process”—short for the Process Church of the Final Judgment—and were scary but compelling in their intensity. Never alone, they stood in groups on the midtown corners in their quasimilitary black uniforms.

Scientology wasn’t so well-known at the time, but cults, communes, and radical religious movements would come and go all the time. I wasn’t aware completely of Scientology or the Process Church, but I respected the commitment it took for these guys to stand and deliver in midtown to a straight bunch of bros. They roamed around downtown as well, among much more sympathetic audiences in the West and East Village.

It was a business, it was a religion, it was a cult; maybe it still is but I don’t think they call it the Process anymore.

I had come to the city to be an artist, but I wasn’t painting much, if at all. In many ways I was really still a tourist, just experiencing the place, having adventures, and meeting people. I experimented with everything imaginable, attempting to figure out who I was as an artist—or if I even was one. I sought out everything New York had to offer, everything underground and forbidden and everything aboveground, and threw myself into it. I wasn’t always smart about it, admittedly, but I learned a lot and came out the other side and kept on trying.

Drawn to music more and more, I didn’t have to go far to hear it. The Balloon Farm, later called the Electric Circus, was on my street, St. Mark’s Place, between Second and Third. The old building the shows were held in had some serious history: from mob hangout, to Ukrainian nursing home, to Polish community hall, to the Dom restaurant. The whole neighborhood was Italian, Polish, and Ukrainian. Every morning, on my way to work, I would see the women in babushkas with their buckets of water and brooms, washing the sidewalks clean of whatever went on the night before. A ritual carryover from the old country.

Trying to keep time at the Mudd Club.

Allan Tannenbaum

One evening, as I walked past the Balloon Farm, the Velvet Underground was playing, so I went inside and into this brilliant explosion of color and light. It was so wild and beautiful, with a set designed by Andy Warhol, who was also doing the lights. The Velvets were fantastic. John Cale brilliant, with his droning, screeching electric viola; proto-punk Lou Reed with his hypercool, drawling delivery and sneering sexuality; Gerard Malanga, gyrating around with his whip and leathers; and the deep-voiced Nico, this haunting, mysterious Nordic goddess . . .

Another time, I saw Janis Joplin play at the Anderson Theater. I loved the physicality and the sensuality of her performance—how her whole body was in the song, how she would grab the bottle of Southern Comfort on the piano and take a huge slug and belt out her lines with crazed Texan soul. I’d never seen anything like her onstage. Nico had a very different approach to performing; she just stood there, still as a statue, as she sang her somber songs—much like the famed jazz singer Keely Smith, with the same stillness but a different kind of music.

I would go see musicals and underground theater. I bought Backstage magazine and I’d take notes on all the auditions and then join the endless lines of hopefuls who, along with me, never got past first base. There was also a strong jazz scene on the Lower East Side with haunts like the Dom, the renowned Five Spot Cafe, and Slugs’. At Slugs’, in particular, you’d get to hear luminaries like Sun Ra, Sonny Rollins, Albert Ayler, and Ornette Coleman—and find yourself at a table next to Salvador Dalí. I met a few of the musicians. I remember showing up and sitting in on a couple of loose, “happening”-like gatherings, the Uni Trio and the Tri-Angels—free, abstract music where I sang a bit or chanted and banged some percussion instrument or other. That was the same thing we did in the First National Uniphrenic Church and Bank. The leader was a guy from New Jersey named Charlie Simon who later christened himself Charlie Nothing. He made sculptures out of cars that he called “dingulators” that you could play like guitars. He also wrote a book called The Adventures of Dickless Traci, a detective novel with a weird sense of humor, but that was later. He was multidimensional in music, art, and literature—a free spirit who was more beat than hippie. And he made me curious. I liked the curiosity because I was curious myself. If any other guy had come along and played me a track from a Tibetan temple with men giggling and growling in the background, I would have liked him too.