Полная версия

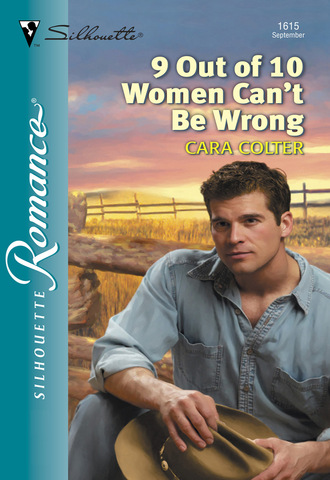

9 Out Of 10 Women Can't Be Wrong

Now, it seemed it was too late to straighten his sister out. Ty would just have to try and save himself.

“Mr. Cringle,” he said carefully, “I’m sorry. My sister has wasted your time. I’m not a calendar model, and I never will be. I’m a rancher. Despite what women who buy calendars might want to believe, there is nothing even vaguely appealing about the kind of work I do. I’m usually up to my ears in mud and crap.”

“Oh, Ty,” Stacey said, “it’s not as if the calendars come in scratch and sniff. Women love those kind of pictures. Sweat. Mud. Rippling muscles. Jeans faded across the rear. You’re perfect for the job, Ty.”

Ty was staring at his sister with dismay. Women liked stuff like that? And how the hell did she know? He realized he hated that she was a full-fledged adult.

“So, hire a model,” Ty said, and heard the testiness in his voice. “If you need some mud, I’ll provide it.”

“Models are so—” Stacey searched for the word, beamed when she found it “—slick.”

Ty could only hope she didn’t know that from firsthand experience.

“Mr. Jordan, I’m sure there were male models among the entries that were posted at the mall. The result of the competition tells me women can tell the difference between someone posing as a rugged, raw, one hundred percent man and the actual man.” Cringle regarded him intently, then said softly, “Ninety per cent is a whole lot of calendars.”

“Yeah, well.” Ty glared at his sister.

“Mr. Cringle, you leave him to me,” Stacey said brightly, but Ty noticed her eyes had tears in them. She’d better not even think she was going to change his mind with the waterworks thing.

It had worked way too many times before. That was part of the problem. Stacey knew exactly how to tug at his heartstrings.

The rest of the world probably thought he didn’t have a heart.

But his little sister knew the truth about him.

When she was seven their mother had died of breast cancer. A year later their father had been killed in a single-car accident, though Ty still wondered how accidental it had been. His father had become a shell of a man since his wife had died.

Ty had been eighteen when the accident occurred. Way too young to be thrust into the responsibility of bringing up a little girl.

But what choice had he had?

Ship her off to an aunt and uncle he barely knew? Let her go to a foster home? Not while he lived and breathed. There had been absolutely no choice. None. His sister had needed him to grow up fast, and he had.

“Why don’t we go have lunch together?” she said to him sweetly. “And we’ll meet Mr. Cringle back here at, say, one o’clock?”

Ty decided not to lay down the law with her in front of her boss. He got up, extended his hand again. “Mr. Cringle,” he said with finality.

But the man looked from him to his sister and back with a twinkle in his eye.

“Until we meet again,” Cringle said.

“Which, hopefully, will be never,” Ty muttered under his breath as he herded his sister toward the door.

“I don’t have time for lunch,” he told her in the hallway. “Calves are hitting the ground as we speak. And I’m not changing my mind about the calendar thing. Get it out of your head. It’s never going to happen. Never.”

Her eyes were welling up with tears. “Ty, don’t be so stubborn.”

The tears reminded him how careful he had to be about using the word never with Stacey. Somehow it always came back to bite him.

He’d said never the first time he’d seen her in makeup, reacting to how the inexpertly applied gunk had stolen the fresh innocence from her face. And then he’d ended up paying for her to take a full day of instructions in makeup application at Face Up and buying all the products she needed. That had been about a whopper of a bill.

He’d said never to her choice of a prom dress, low cut, clinging, way too old for her, and ended up being dragged into places no man in his right mind wanted to go, for days, finding a dress they could both agree on.

And he’d said never to the hippie, which had made the hippie twice as attractive to her, and made him realize that it was no longer his job to say anything to Stacey. Somehow, with so many stumbles on his part and so many mistakes, she had grown up, anyway. Into a young woman who knew her own mind and made pretty reasonable decisions most of the time.

But not this time. “What were you thinking, entering my picture without asking me? Geez, Stacey!”

“It was just a lark. Harriet suggested it.”

Somehow he should have known Harriet was involved in this disaster. Harriet and disaster went together as naturally as peanut butter and jam, saddles and cow horses, trucks and tires.

“Besides,” his sister said blithely, “how did I know you were going to win?”

He sighed. Was she deliberately missing the point? She was wiping tears off her face with the back of her sweater, getting little black smudges all over the white sleeve. Hard to stop noticing stuff like that even though he didn’t buy her clothes anymore.

“Could you take me for lunch?” she said with a little hiccup. “You must need a break from Cookie’s meals by now. Besides, you hardly ever see me anymore.”

He looked at her. His little sister was all grown up. Becoming more a big-city woman every time he saw her. Maybe it wasn’t such a good idea to pass by these chances to be with her.

“Okay,” he said grudgingly. “Lunch. But cheap and fast.” He was thinking along the lines of the Burger in a Bag he had passed on the corner before this office building.

Of course she took him to a little French restaurant that wasn’t cheap and wasn’t even remotely fast.

Despite his annoyance with her, she made him laugh when she told him about how she was hiding a Saint Bernard that she had found, in her little apartment. So far no one had answered the ad she had put in the paper.

“The dog,” she said proudly, “knows how to open the fridge.”

A Saint Bernard who knew how to open the fridge? “That explains why the owners aren’t answering the ad,” Ty commented.

The food came. He’d refused wine—wine with lunch?—but Stacey had ignored him and was pouring him another glass from the carafe of house white that she had ordered.

“You know, Ty, Mom died of breast cancer.”

He took a long sip of wine, then set it down. Okay. Now that Stacey had fed him and lured him into drinking wine with lunch, she was going to try and sucker punch him.

“I hadn’t forgotten,” he said quietly.

“Don’t you think it’s our obligation to fight the disease that took our mother? Don’t you remember how awful it was?”

He suspected he remembered better than she did, since he had been older at the time. He glared at her, seeing the corner she was backing him into. He said nothing and against his better judgment took another sip of the wine.

“That calendar could make the research foundation a lot of money.” She made sure she had his full attention, laid her hand on his. She named a figure.

He nearly spit out the wine. “Are you serious?”

“Dead serious. It’s not very many people who have a chance to give that kind of money to the charity of their choice.”

“Just because I said I don’t want to do it doesn’t mean they aren’t going to go ahead with the calendar.”

“No. But ninety percent of the women who voted liked you—ninety percent. That’s huge, Ty, especially if it translates into them buying calendars. There are 750,000 people in Calgary alone. I estimate 200,000 of them are women. If only fifty percent of them bought calendars, that would be a huge amount of money! In this city alone!”

He could feel his head starting to swim, and not from the wine. “Stacey,” he said carefully, enunciating every word, “I’m not doing it.”

He avoided saying never.

“Oh, Ty.” She sighed and looked at her fingernails. “You wouldn’t even have to come in to the city. You wouldn’t even have to miss an hour’s work.”

“I said no.”

“You wouldn’t even know the photographer was there. The photographer’s all lined up. World class.”

“No.”

“So, it won’t cost you anything, not even time, and you have a chance to contribute so much to a cause that is very meaningful to you, and you say no?”

“That’s right,” he said, and he hoped she didn’t hear the first little sliver of uncertainly in his voice.

“If the calendar was a huge success, I think I’d get a raise. I’d be able to buy a little house. With a backyard for Basil.”

“Basil is the Saint Bernard, I hope.”

She nodded sadly. “I think the landlord suspects I have him.”

“I’m not posing for calendars so you can keep a dog that’s bigger than my horse and has the dubious talent of opening a fridge.” At least, he thought, his sister was planning her life around a dog, and not the hippie. He noticed she hadn’t mentioned the beau today. Did he dare hope he was out of the picture? Or was it because Ty had lost his temper when she had mentioned the hippie and marriage in the same breath once? He decided he didn’t want to know.

She took a little sip of her wine and looked at her lap. She finally said, in a small voice, “You know my chances of getting it are high, don’t you?”

“What?” There. She’d managed to completely lose him with her conversational acrobatics.

“My chances of getting breast cancer are higher than other peoples. Because Mom died of it.”

“Aw, Stacey.”

“The only thing that will change that is research.”

He looked across the table at her and saw her fear was real. He felt his heart break in two when he thought of her in terms of that disease. Wouldn’t he have done anything to make his mother well?

Wouldn’t he do anything to keep his little sister from having to go down that same road? From diagnosis to surgery to chemo to years of struggle to a death that was immeasurably painful and without dignity?

If he was able to raise those kinds of dollars to research a disease that might affect his sister, did he really have any choice at all? If the stupid calendar raised only half as much, or a third as much as his sister’s idealistic estimate, did he have any choice?

Wasn’t this almost the very same feeling he’d had the day a social worker had looked at him and said, “She could go to your uncle Milton. Or to a foster home close to here. If you can’t take her.”

He glared at his sister. He saw the little smile working around the edges of her lips and realized they both knew she had won.

“Don’t even think I’m taking off my shirt,” he said, conceding with ill grace.

“I don’t know, Ty. If you took off your shirt, we might be able to sell a million copies of the calendar.” She correctly interpreted the look he gave her. “Okay, okay,” she said, laughing. “Thank you, Ty. Thank you. I owe my life to you.”

He hoped that would never be true.

She got up out of her chair, came around the table, threw her arms around his neck and kissed him on his cheeks. About sixteen times.

Until everyone at the tables around them were looking over and smiling indulgently.

“This is my brother,” she announced, happily. “He’s my hero.”

Chapter Two

If Tyler Jordan was the most handsome man alive, being angry did not diminish that in the least. Maybe it even accentuated the rugged cut, the masculine perfection, of his sun- and wind-burned features.

And Harriet Pendleton Snow knew he was angry, even before he spoke. The energy bristled in the air around him.

“I was expecting a man,” he said, impatience flashing in his dark eyes. He looked down at a scrap of paper in his hand, and she caught a glimpse of bold, impatient handwriting. “Harry Winter.”

“Harrie Snow,” she corrected him. “That would be me.” He hadn’t recognized her. And she didn’t really know whether to be pleased or hurt by that.

A lot of things had changed in four years.

Outwardly. Inwardly she was doing the same slow melt she had done the first time she had met her best friend’s brother. She had been twenty-two years old when she had first met her best friend’s brother.

Standing right here in this same driveway, the little white frame house behind them, a larger barn behind that, the rolling hills of the Rocky Mountain foothills stretching into infinity on all sides of them, and all of that majesty fading to nothing when his eyes had met hers.

Dark and full of mystery.

Over the years she had tried to tell herself it was other things that had stolen her breath so completely that day.

The immensity of the land.

The romance of the ranch.

The fragrance of the air.

But standing before him now, she was not so sure.

“I find it hard to believe a woman like you is named Harry,” he snapped.

“Like me?” she said. “What does that mean?” Personally she found it even harder to believe that a perfectly rational woman like her mother had looked down at a squirming red-faced bundle of life and seen a Harriet. It was a name she hated and had been trying to lose for years.

He rolled a big shoulder, irritated, gestured. “Like you,” he said. “Polished, pretty—”

Polished. Which meant all the hours spent choosing just the right outfit, until her bed and her floor had been littered with discards, had been well spent. It meant that the new haircut had succeeded, for the time, in taming her wild curls. It meant her new hair color, copper, instead of plain old red, was as sophisticated as she’d hoped. It meant maybe it wasn’t so ridiculous to try to match your lip shade with your nail enamel.

Pretty. He’d called her pretty. For a girl who had grown up thinking of herself as plain at best, homely at worst, they were words she could never hear enough of.

But, before she had a chance to savor that too deeply, it sank in that he hadn’t exactly said pretty as if he thought it was a good thing.

“—an absolute pain around a ranch,” he was saying. “Were you going to ride a horse in a skirt, or is that supposed to put me in the right frame of mind to have my picture taken?”

Was he crankier than he had been back then? Stacey said he was perpetually cranky, but that was not what Harriet had seen in the week she’d been here four years ago.

She’d seen a young man who had shouldered a huge responsibility, defying the fact he probably was ill-prepared to act as anybody’s parent. She had seen he wore sternness like a tough outer skin so his sister wouldn’t see how easily she could have anything she wanted from him because he loved her so.

That love, despite his efforts to disguise it, had been just below the surface that whole week, in the tolerance he had shown both of them, even after the unfortunate accidents.

Accidents caused because Harriet wanted so badly to do everything right, was so nervous around him, so afraid she would say exactly the wrong thing, do exactly the wrong thing. She had wanted him to see her as grown-up and mature.

So of course he had seen her as a kid.

And of course she had spent the entire week doing things wrong, clumsily, self-consciously aware of the newfound feeling inside her.

She would have absolutely died if he’d thought of her as pretty back then.

Because she had fallen in love with him within minutes. Maybe even seconds.

She knew it to be ridiculous now. From the perspective of a woman who had had four years to think about it, to travel the world, to experience many adventures, to marry badly, she knew how ridiculous her younger and more naive self had been.

When she had seen the results of the vote conducted at the Sunny Peak Mall she had known how ridiculous her twenty-two-year-old self had been.

Ridiculous, but not alone.

Women loved him, pure and simple.

She had been given the rarest of things—a second chance. To prove she could be competent, that she was not in the least clumsy or accident prone.

And she had a second chance for him to see her as attractive, the thick bottle-bottom glasses no longer a necessity because of the miracle of laser surgery.

Her teeth as straight and white as money and time and steel could make them.

She knew how to dress now in a way that made her height and slenderness an asset. He might not like the skirt, but she hadn’t missed how his eyes had touched on the length of her legs. Her tendency to freckle was becoming less with each year, revealing a startling, lovely complexion underneath. She had learned how to use makeup to show off her eyes and her cheekbones. Some days, like today, she could almost tame the wild mop of her hair.

But most of all she had been give a second chance to prove she was not in love with him.

Not even close. She had been a gauche and unworldly young woman the first time she had met Tyler Jordan. Male influences had been somewhat lacking in her life, as her mother had been a single parent. She had one sister. Despite her height, or maybe because of it, Harriet had always been invisible to the boys in high school and then, disappointingly, in college.

No wonder she had been so completely bowled over by Ty Jordan. In his form-hugging jeans, with those arm muscles rippling, his straight teeth flashing, he’d exuded a male potency, completely without thought on his part, against which she had been defenseless. Even his silences, to her, had seemed to be charged with some male magic that was both foreign and exciting.

But she was not a naive young girl anymore, and she had a secret agenda here. To take back a heart she had given when she hadn’t known better. To take back her power.

A deep, muffled woof reminded her of the surprise she had for him. Not a good start in proving herself, but not her fault.

“Stacey asked me to bring Basil out. Her landlord is on to him, and she’s going to get evicted.”

“Basil?” Tyler was peering over her shoulder. She glanced back. The dog had his big nose pressed mournfully against the window of her small car and was looking at them with pleading, red-rimmed eyes.

“The Saint Bernard?” he asked, incredulous. “My sister sent me the Saint Bernard that knows how to open a fridge? I don’t believe this.”

“Don’t shoot the messenger,” she said, leaning in carefully and hooking up the leash. The interior of her car had a slightly raunchy odor to it, which she could only hope was not also clinging to her.

“Don’t tempt me,” he said sourly.

Should she just tell him who she was? But then he would be expecting the worst from her from the very beginning. How could it be a real second chance if he had preconceived notions? If he thought of her as the Harriet who blushed every time she spoke and choked on her food at dinner because he even made her self-conscious about chewing?

The dog barreled out of the car as soon as she flipped the seat forward, loped to the end of its lead, reared up and placed its saucer-size paws on Tyler’s chest and licked his face.

She wondered if Basil was female. The man was irresistible.

Except Harrie planned to resist him. This time everything was going according to her plan. She was a professional photographer. She’d been in war zones. She’d traveled the world. She knew how to stay calm while under fire.

Under fire. How about on fire?

She’d worked with some of the world’s most attractive men and made the mistake of marrying one of them. She should be immune to their charms.

And she was!

But much of Ty Jordan’s charm was in the fact he was unaware he possessed it. If he had any idea that he was infinitely appealing, he shrugged it off as unimportant, not an asset that helped him produce cattle or run a ranch or raise a younger sister.

And he was more than good-looking. Eighteen hundred women had seen that right away, and placed their one precious checkmark, their vote for the perfect calendar guy, beside his name and picture.

He was tall, at least two inches taller than Harriet’s embarrassing five foot ten. His shoulders were enormous and mirrored the strength that had allowed him to stand firm even when the beluga-size dog launched itself at him.

And his shoulders weren’t enormous because of four days a week power lifting at the gym, either.

They were enormous from throwing bales and breaking green colts and wrestling cattle.

“Get down,” he ordered the dog, and backed up the firmness of the command by removing the paws from his chest and shoving on the dog’s huge head. With the other arm he swiped his face where the dog had slurped on him.

The simple movement made the sun gleam off the dark hairs on arms that rippled with sinewy muscle. Harrie noticed how the short sleeves of the T-shirt stretched over the bulge of his biceps, molding them. His arms were sun browned, even this early in the year, and his forearms were corded with muscle, his wrists big and square.

The shirt, decorated now with two large paw prints and a splotch of drool, hugged the mounds of deep pectoral muscles, then tapered over broad, hard ribs to a flat waist. The T-shirt was tucked into faded jeans, belted with a scarred brown leather belt. The buckle was worn casually, but it winked solid silver, and Harriet saw it depicted a horse, head down and back arched, trying to get rid of a rider.

Black lettering proclaimed: Wind River Saddle Bronc Champion.

It suddenly occurred to her that her interest in the buckle had put her eyes in the wrong vicinity for too long.

She looked up swiftly.

He had folded his arms over his chest and was looking at her sardonically.

“Do you ride broncs?” she asked, just to let him know she had read the buckle in its entirety.

“No,” he replied curtly.

“That’s too bad,” she said, flashing him what she hoped was a professionally indifferent smile. “It would have made a great photograph.”

He narrowed his eyes. “Get this straight right now. We are not organizing my life for your photo ops. You’re going to follow me around, snap a few pictures, and go home.”

She was thinking of the belt buckle. Stacey had told her he went to rodeos before his parents had died, leaving him with Stacey. Before a boy had to become a man. Facts, she reminded herself, that she was not supposed to know.

And yet facts that would help her capture the essence of him on film, an essence he seemed particularly eager not to reveal as he stood there glowering at her.

But it was the essence of him that made him so teeth-grindingly sexy.

She reminded herself she was a photographer now. Not a starstruck kid. He wanted her to be intimidated by him and she could not allow herself that luxury. She was entitled to look at his face. To study it. To know it.

And so she did.

He had dark hair, the midnight black of a summer sky just before the storm. His hair was close-cropped, sticking up a touch in the front. His face was perfection, and she knew, because she had photographed the faces of some of the world’s most perfect men. Or men who were considered perfect in the looks department, anyway.

She looked at his face and tried to dissect the appeal of it. It had strong lines, particularly the line from his jawbone to his chin. His chin was square, the cleft so faint it could almost be overlooked. A good photograph would show it, though.

His cheekbones were high, and the hollow from the edge of his mouth to the line of his jaw was pronounced. His lips were full and firm and were bracketed by faint lines, stern and down turned. His nose was strong and straight. The faint white ridge of a scar at the bridge of it only underscored his rugged masculine appeal.

But she knew, finally, it was his eyes that took him over the edge, from a nice-looking guy to something beyond. His eyes were almond shaped, fringed with a spiky abundance of black lash. The eyes themselves were the dark rich brown of melted chocolate, but it was the look in them that defined him.

Unflinching. Steady. Calm. Strong. Deep.

And yet some mystery resided there, too. It was not exactly wariness, but a certain aloofness. His eyes told his story: that he was a man who chose to walk alone, who knew his own strength completely and relied on it without thought or hesitation.