Полная версия

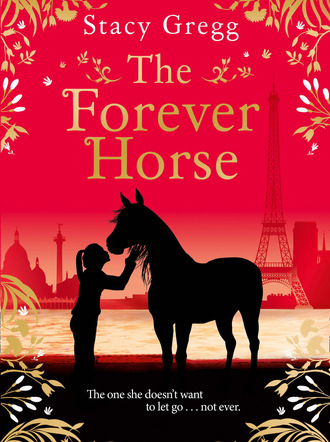

The Forever Horse

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2020

Published in this ebook edition in 2020

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Text copyright © Stacy Gregg 2020

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2020

Cover images and decorative illustrations © Shutterstock

Stacy Gregg asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of the work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008332358

Ebook Edition © October 2020 ISBN: 9780008332365

Version: 2020-09-11

For Maalika

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1: Going Once, Going Twice …

Chapter 2: The Thirteen-Million-Dollar Horse

Chapter 3: The Chance of a Lifetime

Chapter 4: The Diary of Rose Bonifait

Chapter 5: The Horse Guards

Chapter 6: The Stag and the Pheasant

Chapter 7: The Wheelchair Mystery

Chapter 8: I Hate Paris in the Springtime

Chapter 9: Terror at the Louvre

Chapter 10: Flamants Roses

Chapter 11: Death’s Dark Spectre

Chapter 12: Wild Horses

Chapter 13: The Black Bag

Chapter 14: The King Tide

Chapter 15: The Hammer Falls

Chapter 16: Gardians of the Camargue

Chapter 17: Sold!

Epilogue

Keep Reading …

Books by Stacy Gregg

About the Publisher

The crowd gathered in the golden chamber of the famous Paris auction house had come tonight with their wallets bulging. Elegant ladies in sparkling evening gowns sat on high-backed gilt salon chairs, clutching bidding paddles in their manicured hands, while their well-dressed husbands sat beside them looking nervous at the amount of money they were about to spend. Already tonight a small fortune had gone under the hammer. The annual auction of works by the graduates of the Parisian School des Beaux-Arts always attracted the clever art collectors who knew that one day the paintings they picked up in this room for relative peanuts could snowball in value and be resold for millions.

Throughout the evening the bidding had been steady but unremarkable. Now, though, there was an electric tension in the room as two men dressed in white coats and gloves carried the next painting to the front and placed it gingerly on the easel beside the auctioneer.

At the very back of the auction chamber, Maisie rose on tiptoes to get a better view. Crammed in, where it was standing room only, she was terrified she would do something dumb, like raising her hand to scratch her nose and bidding by mistake. There was no way she could afford to buy this painting! Which was ironic, really, since Maisie was the artist who had painted it.

“Lot number sixty-seven!” the auctioneer, Monsieur Falaise, announced to his audience. “This substantial work, in oil on canvas, is entitled, Claude.”

Monsieur Falaise, a thin man with a pointy chin, scanned the faces of the wealthy art patrons and felt certain that he knew which bidders would raise their paddles for this one. Over the years, he had developed an instinct for such things. So far tonight, he had watched as the bidders fought over various works of modern art – abstract and bold. This new painting, Claude, was quite the opposite of all that had gone before. The portrait of the black horse was in the mode of the classical realist masters. It was so detailed, and so lifelike. To think that it had been painted by a thirteen-year-old girl! Monsieur Falaise shook his head in disbelief. The work was so mature, and it was not just that it was magnificent in its technicalities. No, it was the heart that it possessed. The painting was imbued with such a depth of emotion it was impossible to gaze upon it without being reduced to tears. Monsieur Falaise wasn’t ashamed to say that his own eyes had welled up a little when he saw it for the first time. And even now, in the thrust and clamour of the auction room as the bidders prepared themselves for the fierce battle ahead, he could see the patrons dabbing their eyes to quell their tears as a profound solemnity filled the room. For Claude, the subject of this remarkable work of art, was more than just a horse. For the people of Paris he embodied so much of what made the city great; looking upon him made hearts break. And art that makes a heart break is always worth a fortune.

“Who will open the bidding at five thousand euros?”

At the back of the room Maisie let out a squeak. Five thousand euros! It was a staggering figure! The other works the crowd had bid on so far that night had been much cheaper. Most of them ultimately sold for less than two thousand euros. To launch the bidding straight off at such a high figure was surely madness? But Monsieur Falaise knew two things: he knew his audience, and he knew precisely what this painting, at centre stage right now, meant to the people of Paris. And he was right. Within a split second of the bid being announced there was a paddle held aloft in the front row in reply.

“I have five thousand bid!” Monsieur Falaise snapped into action. “Alors! We are underway! Who will give me six thousand?”

Straight away, another paddle went up.

“I have six, six. Who will give me seven? Yes! Seven …”

At the back of the room, Maisie watched silently as the price of the painting – her painting – continued to climb. Soon, the price was at ten thousand euros. Then it climbed higher still! Leaping up by a thousand euros at a time, again and again, until the bid rapidly reached twenty thousand. Even then, the paddle-holders didn’t slow, and soon twenty became thirty and thirty became forty!

There was a moment, at forty-five thousand, when a woman in the front row wearing a Chanel suit and jet-black sunglasses, decided to trump all the other bidders and proclaimed in an icy tone that she was raising the bid to fifty-one thousand, and a mutual sigh of defeat swept the room. Then, a grey-haired gentleman in a cravat came straight back at her and proclaimed “Fifty-three!” and the bidding was off again!

All the while, as the price climbed ever higher, Maisie felt more and more anxious. In this room, with Claude’s black eyes staring at her, she was suddenly gripped with claustrophobia and remorse. How ridiculous to come here now when the real Claude was in such pain and the clock was ticking! What had she been thinking?

Maisie turned to leave, but the crowd were pressed together like sardines.

“I’m sorry! I have to go!” She began to try and push her way out, but the occupants of the auction room were so intently focused on the drama that was unfolding before them they refused to budge. Maisie tried again, in French this time. “Je suis desolé! Pardon, pardon …”

Her pleading had no effect. Maisie could feel the room closing in on her, her heart racing in panic.

“Please! I have to go!”

And then, as if by a miracle, the crowd parted, and there was Nicole Bonifait, Maisie’s patron, so-to-speak, right in front of her, clearing the people out of the way, grasping Maisie’s wrist to guide her through.

“It’s OK, Chou-chou,” Nicole said. “Come with me now. I have you!” and Maisie felt Nicole’s arms around her, ushering her through the crush, until a moment later they were out of the room into the foyer and then through the front doors, stumbling down the marble stairs on to the wide Parisian street below. Maisie was taking deep breaths, her hands on her knees as Nicole barked at one of the waiters at a pavement café nearby to bring them one of his chairs. Tout de suite!!

The waiter hastily obliged, and Nicole sat Maisie down in the middle of the street and told the waiter to bring them water.

“Here, drink this.” Nicole gave a fluted glass full of fizzy water to Maisie, who gratefully slugged it back in a single gulp. Her head was spinning.

“I’m fine,” Maisie insisted. “Nicole, I need to go –”

“Oui, oui, Petit Chou-chou Anglaise,” Nicole soothed, “but take a moment first to catch your breath.”

Petit Chou-chou Anglaise. Nicole’s nickname for Maisie. It meant Little English Cabbage. When Nicole had first told Maisie this, she thought it perhaps was supposed to be an insult, but Nicole assured her it was quite affectionate! Nicole Bonifait was half-British herself, as she’d pointed out to Maisie when they’d first met. And in a way, it was Nicole’s English ancestry that had created the art scholarship that had changed everything and set Maisie off on this whole unbelievable adventure. Six months ago Maisie had been an ordinary schoolkid, living on a council estate in Brixton, South London. Now, here she was, sitting outside Lucie’s, the most prestigious auction house in the whole of Paris, while the rich and the fabulous of the city tried to outbid each other over her art.

“Do you feel well enough to go back inside now?” Nicole asked her. “This is your moment of glory. Your work is going to fetch a record price, I think.”

Maisie shook her head. “I’m not going back in. I don’t care about the painting. I want to go back to Claude.”

Nicole gave her hand a squeeze. “I understand completely,” she said. “Who cares about a room full of bourgeoisie? Tonight, of all nights, you should be with him, no?”

“Yes,” Maisie replied. “I’m not being ungrateful Nicole … I know how much this means to you …”

“Don’t be silly, Chou-chou!” Nicole hugged Maisie tight. “Go to him now! We have done what we can, but if these are truly to be his final hours you should be at his side.”

Maisie found that her legs were surprisingly jelly-like when she rose from her chair, but she felt a steely determination that drove her on, made her put one foot in front of the other as she turned away from the auction house, heading down the boulevard Henri IV. Lucie’s was walking distance from the stables of the Célestins, home to the mounted French police known as the Republican Guard. But as Maisie regained her strength that walk soon became a run. And it was as she was running that the tears began to come. She sniffled and choked as she wiped them away and kept running onwards through the crossroads. Car horns honked as she ignored the lights, cyclists yelled at her as she sped in front of their bikes. Then, at last, lungs aching, she reached the front gates of the Couvent des Célestins.

It was amazing to think that nearly two hundred horses lived right here in these opulent stables in the heart of Paris. These were city horses, accustomed to the hum and buzz of urban life, cared for by their riders, the noble gendarmes, the policemen of the Republican Guard.

Maisie was lucky. Alexandre, of all people, was on gate duty tonight – thank God! He had his feet up and was reading the paper and he got a shock when she knocked on the sentry box window to be let inside.

“Maisie?” He dropped the paper immediately. “I thought you were at the auction?”

Maisie’s heart was still pounding from the run. “Alexandre, please? May I come in?”

Alexandre frowned. “You shouldn’t be here, Maisie, not now … They will be coming for him soon.”

Alexandre tried to resist but he could see the quiver of Maisie’s bottom lip and the tear stains on her cheeks. He gave a sigh and reached beneath the desk of the sentry box, pressed the button, and the automatic doors swung open.

“If the guards come, you make yourself invisible, yes?” Alexandre looked hard at her, making his point clear. “You are not here.”

“I am not here,” Maisie agreed. “I am a shadow.”

“That’s my girl,” Alexandre said. And then, with a wave of his hand, “Hurry now! A shadow moves quickly! Go to him!”

Maisie slipped briskly through the gates and across the courtyard, dashing between the clipped hedges and fountains to reach the stable block, sticking close to the walls where the security lights did not reach. She tiptoed across the cobblestones, creaked through the doors until, at last, she had made her way to Claude’s stall.

“Claude?” Maisie spoke his name as she pulled the bolt and opened the door. Part of her was afraid at that moment that they would have sneaked in and come for him and he’d already be gone. But no. He was there. He nickered softly at the sight of her, and she met his dark, soulful eyes. The very same eyes she had recreated in the painting being auctioned right now at Lucie’s.

Oh, but in real life he was so much more handsome! Of all the many beautiful and noble-blooded stallions who lived here in the stables of the Célestins, he was the most breathtaking. Jet-black with four white socks on his legs and a star on his forehead. A classic Selle Français, he had always turned heads when he was ridden on parade. That first day that Maisie had seen him, he had stood out above all the rest and she knew he was special – as indeed he had proved to be.

“Hello, my brave boy.” Maisie spoke softly, and the stallion raised up his elegant crest to nicker to her. Then, exhaustion and pain overcame him and he let his mighty head fall between his forelegs like a dying swan in a ballet.

“Claude,” Maisie knelt beside him and, using all her strength, she helped to lift his head, cradling him in her arms.

“I know you’re in such pain, Claude,” she whispered as she stroked his forelock, “but you won’t need to be brave for much longer. I promise you, when they come for you, no matter how much it breaks my heart, I will stick by you. I’ll be with you at the end. I promise, I promise …”

When Maisie had first come to Paris, she had marvelled at the beauty of this city. Her favourite time was the early morning when the sunrise washed the dove-grey rooftops an iridescent pink and the River Seine seemed to be made of molten gold. As an artist, she loved the dawn and its transformative, divine light. But tonight, as she held Claude tight in her arms, she dreaded the sunrise with all her heart. For when the night had ended, and the guards of the Célestins returned, Claude would be taken from her. And the light would be gone from Paris forever.

One year earlier …

The first horse I ever loved cost thirteen million dollars. And he wasn’t even real. His name was Whistlejacket and he was a portrait hanging on the wall at the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square. OK, so it was the painting and not the actual horse that was worth all that money, but even so.

My dad had taken me to the gallery to look at Whistlejacket one rainy Sunday afternoon. I was five at the time – too young, really, to take to a gallery, but Dad says that’s how he knew I was different from other kids, because instead of being bored I was in my element amongst all those famous paintings. I took in Van Gogh’s brilliant yellow sunflowers, Claude Monet’s soft and misty irises and Botticelli’s languid reclining beauties, Venus and Mars – and I explained to Dad, my little-kid voice brimming with authority, exactly what techniques I envisaged the painters must have used, and what I liked about the composition and the colours. Dad says I was always certain about what I loved and hated about art, right from the start. I didn’t get the abstract stuff, or the surrealists. I liked art that really looked like things – landscapes and animals and portraits.

There were some amazing paintings in the gallery that day, but when I saw Whistlejacket, they all disappeared, and he was everything to me.

He was a beautiful horse – deep chestnut with a flaxen mane and a thick honey-blond tail that flowed almost to the ground. There was one perfect white sock on his near hind leg and his haunches were muscled, but his limbs were delicate and his neck set perfectly into his elegant shoulders. As he reared up on his hind legs, he turned to look at me. His dark liquid-brown eye had such a soulful expression that it seemed impossible that he wasn’t a real horse. To think that an artist had created all of this with his hands!

“I want to take him home,” I told Dad, laughing.

“We can’t,” my dad said. “He belongs here, and besides – that painting’s worth thirteen million pounds.”

I was heartbroken until we went to the gift shop and Dad bought me a box of paints and a postcard of the painting.

“You can make your own horse now,” he said.

That afternoon, I tried to paint my own Whistlejacket. I struggled hard to get the proportions right – to recreate his broad neck and the dip of his back and the curve of his rump. The legs were tricky! Especially his hooves. I found my new paints were a blunt instrument, too drippy and squishy, and so I swapped to a plain HB pencil. Using the pencil wasn’t as colourful or fun, but I wasn’t interested in painting like a little kid. I wanted to make my horse perfect, and with a pencil I could refine my picture, reworking the lines, rubbing out the bad patches and redoing them until I was satisfied.

I did lots of drawings of Whistlejacket, and each time I was finished I would show them to Dad and he’d put them on the fridge. At first they were pretty clumsy, but I got better fast. I mean, I was only five and most five-year-olds do drawings that just look like scribbles – but pretty soon I could do ones that really looked like a horse. I remember I did one that was really good, and it almost looked like him. My dad looked at it for a long time in admiration and then he said. “Maisie, you’re a prodigy.”

“What’s a prodigy?” I asked.

“Someone who is very, very good at something at a very young age. Like Mozart.”

“Did he draw horses then?”

“No. He played the piano.”

“What’s the point of being good at that?”

“Different people are good at different stuff,” Dad said.

I decided at that moment that I would only ever be good at drawing horses.

The next weekend, we caught the bus to Hyde Park. Dad had bought me a new sketch pad with thick, white textured pages, and he’d made us lunch to take with us.

“There are horses here,” Dad explained. “They keep them in stables not far away, and they’re allowed to ride them through the park.”

We sat on the grass beneath the trees that lined Rotten Row and waited, and within minutes we saw our first real-life horses! A pair of black-and-white cobs with fluffy feathered legs, Roman noses and broad backsides. I did a sketch of them as best I could as they went past, and then at home that night I painted over my original drawing to get the light and the colours right.

“Do you really think I’m a podgy?” I asked Dad. He was confused. Then he got what I meant.

“Not a podgy,” he said. “Prodigy. It means you are a young genius. You have a gift.”

So … yeah, I’m a prodigy. Or at least I was. If you look it up in wikipedia a prodigy has to be under ten! And I’m twelve now, almost thirteen, so I’m way over the hill – that is modern life for you. Anyway the prodigy thing is not all it’s cracked up to be. You’d think that being an art genius would be a good thing. I mean, I’m pretty sure everyone loved Mozart when he was a kid. But it’s totally not working out like that for me. For a start, Mrs Mason, my teacher at Brixton Heights Academy, is a total cow and thinks drawing in class is, like, a crime or something. As far as she is concerned, it would be better to be Adolf Hitler than to draw horses. At least that was the impression she gave at the parent-teacher conferences.

“She’s wasting everyone’s time and disrupting my class,” Mrs Mason said.

“Because drawing horses isn’t part of your art curriculum?” my dad asked.

“Mr Thompson,” Mrs Mason said icily. “Maisie doesn’t restrict her drawing to during art class. She is drawing horses all – the – time.”

Mrs Mason reached below her desk.

“Maisie’s maths book,” she said as she held it up and flicked through the pages. There were no sums, no formulas on the cross-hatched pages. Just horses. Lots and lots of horses.

“I could show you her English book, which is exactly the same.” Mrs Mason continued her character assassination. “She draws in science; even during religious studies! She is the most impossible, unteachable child I have ever encountered in all my years as an educator …”

Mrs Mason was so worked up that when the bell went off to signal it was time for the next parent, she ignored it! James McCavity, who was sitting with his mum in the row of chairs behind us, waiting for his turn, gave me a sympathetic smile as I sat there dumbly while she ranted. When the bell rang a second time and she was still going, teachers from the other classes who were in the school hall began to stop talking and look over at Mrs Mason, who had got quite red in the face. And then, at last, when she had run all the way to the end of her tether, my dad spoke up.

“Did you ever look at her drawings, Mrs Mason?”

“I’m sorry?” Mrs Mason was confused. “What does that have to do with it? I’m talking about Maisie’s bad manners in class.”

My dad shook his head and sighed. “Are you aware that Maisie’s mum died when she was a newborn?”

Mrs Mason looked taken aback at this. “I’m sorry,” she stammered. “I wasn’t … I didn’t know.”

“No. Of course not,” Dad said. “So you didn’t know that I’m a solo dad. I raise Maisie on my own and my time is tight. I work a sixty-hour week and I’ve had to make excuses to get off work early today. I came here expecting we were going to discuss what your school was doing to encourage and extend my gifted child.”

“Mr Thompson!” Mrs Mason bristled back. “Even Picasso had to go to school you know.”

Dad laughed and said, “You know what, Mrs Mason? You’re dead wrong, but that’s the one interesting point you’ve made today.”

Afterwards, as we walked home, Dad told me about Pablo Picasso, one of the most famous artists in the world, and how Picasso was accepted into a fancy art school when he was just thirteen.

“I bet Mrs Mason wouldn’t tell off Picasso,” Dad grumbled.

“I think she probably would,” I replied.

In a weird way, though, we had Mrs Mason to thank for what was to come. If it hadn’t been for her, Dad would never have got the idea into his head that I could be like Picasso too. He was hatching a plan right there as we walked home, but he didn’t talk about it with me yet. He just told me that Mrs Mason was a silly old sausage, and we got fish and chips and Dad told me to at least try and look like I was paying attention in class in future to keep Mrs Mason from calling him again.