полная версия

полная версияLouisa May Alcott : Her Life, Letters, and Journals

The little friend received the dear plummy cake, and I a kiss and my first lesson in the sweetness of self-denial,–a lesson which my dear mother beautifully illustrated all her long and noble life.

Running away was one of the delights of my early days; and I still enjoy sudden flights out of the nest to look about this very interesting world, and then go back to report.

On one of these occasions I passed a varied day with some Irish children, who hospitably shared their cold potatoes, salt-fish, and crusts with me as we revelled in the ash-heaps which then adorned the waste lands where the Albany Depot now stands. A trip to the Common cheered the afternoon, but as dusk set in and my friends deserted me, I felt that home was a nice place after all, and tried to find it. I dimly remember watching a lamp-lighter as I sat to rest on some doorsteps in Bedford Street, where a big dog welcomed me so kindly that I fell asleep with my head pillowed on his curly back, and was found there by the town-crier, whom my distracted parents had sent in search of me. His bell and proclamation of the loss of "a little girl, six years old, in a pink frock, white hat, and new green shoes," woke me up, and a small voice answered out of the darkness,–

"Why, dat's me!"

Being with difficulty torn from my four-footed friend, I was carried to the crier's house, and there feasted sumptuously on bread-and-molasses in a tin plate with the alphabet round it. But my fun ended next day when I was tied to the arm of the sofa to repent at leisure.

I became an Abolitionist at a very early age, but have never been able to decide whether I was made so by seeing the portrait of George Thompson hidden under a bed in our house during the Garrison riot, and going to comfort "the poor man who had been good to the slaves," or because I was saved from drowning in the Frog Pond some years later by a colored boy. However that may be, the conversion was genuine; and my greatest pride is in the fact that I lived to know the brave men and women who did so much for the cause, and that I had a very small share in the war which put an end to a great wrong.

Another recollection of her childhood was of a "contraband" hidden in the oven, which must have made her sense of the horrors of slavery very keen.

I never went to school except to my father or such governesses as from time to time came into the family. Schools then were not what they are now; so we had lessons each morning in the study. And very happy hours they were to us, for my father taught in the wise way which unfolds what lies in the child's nature, as a flower blooms, rather than crammed it, like a Strasburg goose, with more than it could digest. I never liked arithmetic nor grammar, and dodged those branches on all occasions; but reading, writing, composition, history, and geography I enjoyed, as well as the stories read to us with a skill peculiarly his own.

"Pilgrim's Progress," Krummacher's "Parables," Miss Edgeworth, and the best of the dear old fairy tales made the reading hour the pleasantest of our day. On Sundays we had a simple service of Bible stories, hymns, and conversation about the state of our little consciences and the conduct of our childish lives which never will be forgotten.

Walks each morning round the Common while in the city, and long tramps over hill and dale when our home was in the country, were a part of our education, as well as every sort of housework,–for which I have always been very grateful, since such knowledge makes one independent in these days of domestic tribulation with the "help" who are too often only hindrances.

Needle-work began early, and at ten my skilful sister made a linen shirt beautifully; while at twelve I set up as a doll's dressmaker, with my sign out and wonderful models in my window. All the children employed me, and my turbans were the rage at one time, to the great dismay of the neighbors' hens, who were hotly hunted down, that I might tweak out their downiest feathers to adorn the dolls' headgear.

Active exercise was my delight, from the time when a child of six I drove my hoop round the Common without stopping, to the days when I did my twenty miles in five hours and went to a party in the evening.

I always thought I must have been a deer or a horse in some former state, because it was such a joy to run. No boy could be my friend till I had beaten him in a race, and no girl if she refused to climb trees, leap fences, and be a tomboy.

My wise mother, anxious to give me a strong body to support a lively brain, turned me loose in the country and let me run wild, learning of Nature what no books can teach, and being led,–as those who truly love her seldom fail to be,–

"Through Nature up to Nature's God."I remember running over the hills just at dawn one summer morning, and pausing to rest in the silent woods, saw, through an arch of trees, the sun rise over river, hill, and wide green meadows as I never saw it before.

Something born of the lovely hour, a happy mood, and the unfolding aspirations of a child's soul seemed to bring me very near to God; and in the hush of that morning hour I always felt that I "got religion," as the phrase goes. A new and vital sense of His presence, tender and sustaining as a father's arms, came to me then, never to change through forty years of life's vicissitudes, but to grow stronger for the sharp discipline of poverty and pain, sorrow and success.

Those Concord days were the happiest of my life, for we had charming playmates in the little Emersons, Channings, Hawthornes, and Goodwins, with the illustrious parents and their friends to enjoy our pranks and share our excursions.

Plays in the barn were a favorite amusement, and we dramatized the fairy tales in great style. Our giant came tumbling off a loft when Jack cut down the squash-vine running up a ladder to represent the immortal bean. Cinderella rolled away in a vast pumpkin, and a long black pudding was lowered by invisible hands to fasten itself on the nose of the woman who wasted her three wishes.

Pilgrims journeyed over the hill with scrip and staff and cockle-shells in their hats; fairies held their pretty revels among the whispering birches, and strawberry parties in the rustic arbor were honored by poets and philosophers, who fed us on their wit and wisdom while the little maids served more mortal food.

CHAPTER III

FRUITLANDS

MY KINGDOMA little kingdom I possess,Where thoughts and feelings dwell,And very hard I find the taskOf governing it well;For passion tempts and troubles me,A wayward will misleads,And selfishness its shadow castsOn all my words and deeds.How can I learn to rule myself,To be the child I should,Honest and brave, nor ever tireOf trying to be good?How can I keep a sunny soulTo shine along life's way?How can I tune my little heartTo sweetly sing all day?Dear Father, help me with the loveThat casteth out my fear,Teach me to lean on thee, and feelThat thou art very near,That no temptation is unseen,No childish grief too small,Since thou, with patience infinite,Doth soothe and comfort all.I do not ask for any crownBut that which all may win,Nor seek to conquer any worldExcept the one within.Be thou my guide until I find,Led by a tender hand,Thy happy kingdom in myself,And dare to take command.IN 1842 Mr. Alcott went to England. His mind was very much exercised at this time with plans for organized social life on a higher plane, and he found like-minded friends in England who gave him sympathy and encouragement. He had for some years advocated a strictly vegetarian diet, to which his family consented from deference to him; consequently the children never tasted meat till they came to maturity. On his return from England he was accompanied by friends who were ready to unite with him in the practical realization of their social theories. Mr. Lane resided for some months in the Alcott family at Concord, and gave instruction to the children. Although he does not appear to have won their hearts, they yet reaped much intellectual advantage from his lessons, as he was an accomplished scholar.

In 1843 this company of enthusiasts secured a farm in the town of Harvard, near Concord, which with trusting hope they named Fruitlands. Mrs. Alcott did not share in all the peculiar ideas of her husband and his friends, but she was so utterly devoted to him that she was ready to help him in carrying out his plans, however little they commended themselves to her better judgment.

She alludes very briefly to the experiment in her diary, for the experience was too bitter to dwell upon. She could not relieve her feelings by bringing out the comic side, as her daughter did. Louisa's account of this colony, as given in her story called "Transcendental Wild Oats," is very close to the facts; and the mingling of pathos and humor, the reverence and ridicule with which she alternately treats the personages and the notions of those engaged in the scheme, make a rich and delightful tale. It was written many years later, and gives the picture as she looked back upon it, the absurdities coming out in strong relief, while she sees also the grand, misty outlines of the high thoughts so poorly realized. This story was published in the "Independent," Dec. 8, 1873, and may now be found in her collected works ("Silver Pitchers," p. 79).

Fortunately we have also her journal written at the time, which shows what education the experience of this strange life brought to the child of ten or eleven years old.

The following extract from Mr. Emerson proves that this plan of life looked fair and pleasing to his eye, although he was never tempted to join in it. He was evidently not unconscious of the inadequacy of the means adopted to the end proposed, but he rejoiced in any endeavor after high ideal life.

July, 8, 1843.Journal.– The sun and the evening sky do not look calmer than Alcott and his family at Fruitlands. They seemed to have arrived at the fact,–to have got rid of the show, and so to be serene. Their manners and behavior in the house and in the field were those of superior men,–of men at rest. What had they to conceal? What had they to exhibit? And it seemed so high an attainment that I thought–as often before, so now more, because they had a fit home, or the picture was fitly framed–that these men ought to be maintained in their place by the country for its culture.

Young men and young maidens, old men and women, should visit them and be inspired. I think there is as much merit in beautiful manners as in hard work. I will not prejudge them successful. They look well in July; we will see them in December. I know they are better for themselves than as partners. One can easily see that they have yet to settle several things. Their saying that things are clear, and they sane, does not make them so. If they will in very deed be lovers, and not selfish; if they will serve the town of Harvard, and make their neighbors feel them as benefactors wherever they touch them,–they are as safe as the sun.5

Early Diary kept at Fruitlands, 1843Ten Years OldSeptember 1st.– I rose at five and had my bath. I love cold water! Then we had our singing-lesson with Mr. Lane. After breakfast I washed dishes, and ran on the hill till nine, and had some thoughts,–it was so beautiful up there. Did my lessons,–wrote and spelt and did sums; and Mr. Lane read a story, "The Judicious Father": How a rich girl told a poor girl not to look over the fence at the flowers, and was cross to her because she was unhappy. The father heard her do it, and made the girls change clothes. The poor one was glad to do it, and he told her to keep them. But the rich one was very sad; for she had to wear the old ones a week, and after that she was good to shabby girls. I liked it very much, and I shall be kind to poor people.

Father asked us what was God's noblest work. Anna said men, but I said babies. Men are often bad; babies never are. We had a long talk, and I felt better after it, and cleared up.

We had bread and fruit for dinner. I read and walked and played till supper-time. We sung in the evening. As I went to bed the moon came up very brightly and looked at me. I felt sad because I have been cross to-day, and did not mind Mother. I cried, and then I felt better, and said that piece from Mrs. Sigourney, "I must not tease my mother." I get to sleep saying poetry,–I know a great deal.

Thursday, 14th.– Mr. Parker Pillsbury came, and we talked about the poor slaves. I had a music lesson with Miss F. I hate her, she is so fussy. I ran in the wind and played be a horse, and had a lovely time in the woods with Anna and Lizzie. We were fairies, and made gowns and paper wings. I "flied" the highest of all. In the evening they talked about travelling. I thought about Father going to England, and said this piece of poetry I found in Byron's poems:–

"When I left thy shores, O Naxos,Not a tear in sorrow fell;Not a sigh or faltered accentTold my bosom's struggling swell."It rained when I went to bed, and made a pretty noise on the roof.

Sunday, 24th.– Father and Mr. Lane have gone to N. H. to preach. It was very lovely… Anna and I got supper. In the eve I read "Vicar of Wakefield." I was cross to-day, and I cried when I went to bed. I made good resolutions, and felt better in my heart. If I only kept all I make, I should be the best girl in the world. But I don't, and so am very bad.

[Poor little sinner! She says the same at fifty.– L. M. A.]

October 8th.– When I woke up, the first thought I got was, "It's Mother's birthday: I must be very good." I ran and wished her a happy birthday, and gave her my kiss. After breakfast we gave her our presents. I had a moss cross and a piece of poetry for her.

We did not have any school, and played in the woods and got red leaves. In the evening we danced and sung, and I read a story about "Contentment." I wish I was rich, I was good, and we were all a happy family this day.

Thursday, 12th.– After lessons I ironed. We all went to the barn and husked corn. It was good fun. We worked till eight o'clock and had lamps. Mr. Russell came. Mother and Lizzie are going to Boston. I shall be very lonely without dear little Betty, and no one will be as good to me as mother. I read in Plutarch. I made a verse about sunset:–

Softly doth the sun descendTo his couch behind the hill,Then, oh, then, I love to sitOn mossy banks beside the rill.Anna thought it was very fine; but I didn't like it very well.

Friday, Nov. 2nd.– Anna and I did the work. In the evening Mr. Lane asked us, "What is man?" These were our answers: A human being; an animal with a mind; a creature; a body; a soul and a mind. After a long talk we went to bed very tired.

[No wonder, after doing the work and worrying their little wits with such lessons.–L. M. A.]

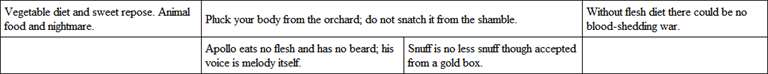

A sample of the vegetarian wafers we used at Fruitlands:–

Tuesday, 20th.– I rose at five, and after breakfast washed the dishes, and then helped mother work. Miss F. is gone, and Anna in Boston with Cousin Louisa. I took care of Abby (May) in the afternoon. In the evening I made some pretty things for my dolly. Father and Mr. L. had a talk, and father asked us if we saw any reason for us to separate. Mother wanted to, she is so tired. I like it, but not the school part or Mr. L.

Eleven years old. Thursday, 29th.– It was Father's and my birthday. We had some nice presents. We played in the snow before school. Mother read "Rosamond" when we sewed. Father asked us in the eve what fault troubled us most. I said my bad temper.

I told mother I liked to have her write in my book. She said she would put in more, and she wrote this to help me:–

Dear Louy,–Your handwriting improves very fast. Take pains and do not be in a hurry. I like to have you make observations about our conversations and your own thoughts. It helps you to express them and to understand your little self. Remember, dear girl, that a diary should be an epitome of your life. May it be a record of pure thought and good actions, then you will indeed be the precious child of your loving mother.

December 10th.– I did my lessons, and walked in the afternoon. Father read to us in dear Pilgrim's Progress. Mr. L. was in Boston, and we were glad. In the eve father and mother and Anna and I had a long talk. I was very unhappy, and we all cried. Anna and I cried in bed, and I prayed God to keep us all together.

[Little Lu began early to feel the family cares and peculiar trials.–L. M. A.]

I liked the verses Christian sung and will put them in:–

"This place has been our second stage,Here we have heard and seenThose good things that from age to ageTo others hid have been."They move me for to watch and pray,To strive to be sincere,To take my cross up day by day,And serve the Lord with fear."[The appropriateness of the song at this time was much greater than the child saw. She never forgot this experience, and her little cross began to grow heavier from this hour.–L. M. A.]

Concord, Sunday.–We all went into the woods to get moss for the arbor Father is making for Mr. Emerson. I miss Anna so much. I made two verses for her:–

TO ANNASister, dear, when you are lonely,Longing for your distant home,And the images of loved onesWarmly to your heart shall come,Then, mid tender thoughts and fancies,Let one fond voice say to thee,"Ever when your heart is heavy,Anna, dear, then think of me."Think how we two have togetherJourneyed onward day by day,Joys and sorrows ever sharing,While the swift years roll away.Then may all the sunny hoursOf our youth rise up to thee,And when your heart is light and happy,Anna, dear, then think of me.[Poetry began to flow about this time in a thin but copious stream.–L. M. A.]

Wednesday.– Read Martin Luther. A long letter from Anna. She sends me a picture of Jenny Lind, the great singer. She must be a happy girl. I should like to be famous as she is. Anna is very happy; and I don't miss her as much as I shall by and by in the winter.

I wrote in my Imagination Book, and enjoyed it very much. Life is pleasanter than it used to be, and I don't care about dying any more. Had a splendid run, and got a box of cones to burn. Sat and heard the pines sing a long time. Read Miss Bremer's "Home" in the eve. Had good dreams, and woke now and then to think, and watch the moon. I had a pleasant time with my mind, for it was happy.

[Moods began early.–L. M. A.]

January, 1845, Friday.– Did my lessons, and in the p. m. mother read "Kenilworth" to us while we sewed. It is splendid! I got angry and called Anna mean. Father told me to look out the word in the Dic., and it meant "base," "contemptible." I was so ashamed to have called my dear sister that, and I cried over my bad tongue and temper.

We have had a lovely day. All the trees were covered with ice, and it shone like diamonds or fairy palaces. I made a piece of poetry about winter:–

The stormy winter's come at last,With snow and rain and bitter blast;Ponds and brooks are frozen o'er,We cannot sail there any more.The little birds are flown awayTo warmer climes than ours;They'll come no more till gentle MayCalls them back with flowers.Oh, then the darling birds will singFrom their neat nests in the trees.All creatures wake to welcome Spring,And flowers dance in the breeze.With patience wait till winter is o'er,And all lovely things return;Of every season try the moreSome knowledge or virtue to learn.[A moral is tacked on even to the early poems.–L. M. A.]

I read "Philothea,"6 by Mrs. Child. I found this that I liked in it. Plato said:–

"When I hear a note of music I can at once strike its chord. Even as surely is there everlasting harmony between the soul of man and the invisible forms of creation. If there were no innocent hearts there would be no white lilies… I often think flowers are the angel's alphabet whereby they write on hills and fields mysterious and beautiful lessons for us to feel and learn."

[Well done, twelve-year-old! Plato, the father's delight, had a charm for the little girl also.–L. M. A.]

Wednesday.– I am so cross I wish I had never been born.

Thursday.– Read the "Heart of Mid-Lothian," and had a very happy day. Miss Ford gave us a botany lesson in the woods. I am always good there. In the evening Miss Ford told us about the bones in our bodies, and how they get out of order. I must be careful of mine, I climb and jump and run so much.

I found this note from dear mother in my journal:–

My dearest Louy,–I often peep into your diary, hoping to see some record of more happy days. "Hope, and keep busy," dear daughter, and in all perplexity or trouble come freely to your

Mother.Dear Mother,–You shall see more happy days, and I will come to you with my worries, for you are the best woman in the world.

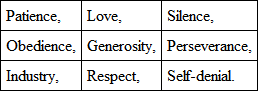

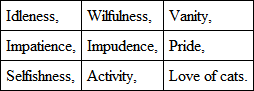

L. M. A.A Sample of our Lessons"What virtues do you wish more of?" asks Mr. L.

I answer:–

"What vices less of?"

How can you get what you need? By trying.

How do you try? By resolution and perseverance.

How gain love? By gentleness.

What is gentleness? Kindness, patience, and care for other people's feelings.

Who has it? Father and Anna.

Who means to have it? Louisa, if she can.

[She never got it.–L. M. A.]

Write a sentence about anything. "I hope it will rain; the garden needs it."

What are the elements of hope? Expectation, desire, faith.

What are the elements in wish? Desire.

What is the difference between faith and hope? "Faith can believe without seeing; hope is not sure, but tries to have faith when it desires."

No. 3What are the most valuable kinds of self-denial? Appetite, temper.

How is self-denial of temper known? If I control my temper, I am respectful and gentle, and every one sees it.

What is the result of this self-denial? Every one loves me, and I am happy.

Why use self-denial? For the good of myself and others.

How shall we learn this self-denial? By resolving, and then trying hard.

What then do you mean to do? To resolve and try.

[Here the record of these lessons ends, and poor little Alcibiades went to work and tried till fifty, but without any very great success, in spite of all the help Socrates and Plato gave her.–L. M. A.]

Tuesday.– More people coming to live with us; I wish we could be together, and no one else. I don't see who is to clothe and feed us all, when we are so poor now. I was very dismal, and then went to walk and made a poem.

DESPONDENCYSilent and sad,When all are glad,And the earth is dressed in flowers;When the gay birds singTill the forests ring,As they rest in woodland bowers.Oh, why these tears,And these idle fearsFor what may come to-morrow?The birds find foodFrom God so good,And the flowers know no sorrow.If He clothes theseAnd the leafy trees,Will He not cherish thee?Why doubt His care;It is everywhere,Though the way we may not see.Then why be sadWhen all are glad,And the world is full of flowers?With the gay birds sing,Make life all Spring,And smile through the darkest hours.Louisa Alcott grew up so naturally in a healthy religious atmosphere that she breathed and worked in it without analysis or question. She had not suffered from ecclesiastical tyranny or sectarian bigotry, and needed not to expend any time or strength in combating them. She does not appear to have suffered from doubt or questioning, but to have gone on her way fighting all the real evils that were presented to her, trusting in a sure power of right, and confident of victory.

Concord, Thursday.– I had an early run in the woods before the dew was off the grass. The moss was like velvet, and as I ran under the arches of yellow and red leaves I sang for joy, my heart was so bright and the world so beautiful. I stopped at the end of the walk and saw the sunshine out over the wide "Virginia meadows."

It seemed like going through a dark life or grave into heaven beyond. A very strange and solemn feeling came over me as I stood there, with no sound but the rustle of the pines, no one near me, and the sun so glorious, as for me alone. It seemed as if I felt God as I never did before, and I prayed in my heart that I might keep that happy sense of nearness all my life.