полная версия

полная версияThe Works of Robert Louis Stevenson – Swanston Edition. Volume 15

Notary. Considered a case?

Dumont. Yes, yes. Charles, you know, Charles. Can he marry? under these untoward and peculiar circumstances, can he marry?

Notary. Now, lemme tell you: marriage is a contract to which there are two constracting parties. That being clear, I am prepared to argue categorically that your son Charles – who, it appears, is not your son Charles – I am prepared to argue that one party to a contract being null and void, the other party to a contract cannot by law oblige or constrain the first party to constract or bind himself to any contract, except the other party be able to see his way clearly to constract himself with him. I donno if I make myself clear?

Dumont. No.

Notary. Now, lemme tell you: by applying justice of peace might possibly afford relief.

Dumont. But how?

Notary. Ay, there’s the rub.

Dumont. But what am I to do? He’s not my son, I tell you: Charles is not my son.

Notary. I know.

Dumont. Perhaps a glass of wine would clear him?

Notary. That’s what I want. (They go out, L.U.E.)

Aline. And now, if you’ve done deranging my table, to the cellar for the wine, the whole pack of you. (Manet sola, considering table.) There! it’s like a garden. If I had as sweet a table for my wedding, I would marry the Notary.

SCENE III The Stage remains vacant. Enter, by door L.C., Macaire, followed by Bertrand with the bundle; in the traditional costumeMacaire. Good! No police!

Bertrand (looking off L.C.). Sold again!

Macaire. This is a favoured spot, Bertrand: ten minutes from the frontier: ten minutes from escape. Blessings on that frontier line! The criminal hops across, and lo! the reputable man. (Reading.) “’Auberge des Adrets,’ by John Paul Dumont.” A table set for company; this is fate: Bertrand, are we the first arrivals? An office; a cabinet; a cash-box – aha! and a cash-box, golden within. A money-box is like a Quaker beauty: demure without, but what a figure of a woman! Outside gallery: an architectural feature I approve; I count it a convenience both for love and war; the troubadour – twang-twang; the craftsmen – (Makes as if turning key.) The kitchen window: humming with cookery; truffles, before Jove! I was born for truffles. Cock your hat: meat, wine, rest, and occupation; men to gull, women to fool, and still the door open, the great unbolted door of the frontier!

Bertrand. Macaire, I’m hungry.

Macaire. Bertrand, excuse me, you are a sensualist. I should have left you in the stone-yard at Lyons, and written no passport but my own. Your soul is incorporate with your stomach. Am I not hungry too? My body, thanks to immortal Jupiter, is but the boy that holds the kite-string; my aspirations and designs swim like the kite sky-high, and overlook an empire.

Bertrand. If I could get a full meal and a pound in my pocket I would hold my tongue.

Macaire. Dreams, dreams! We are what we are; and what are we? Who are you? who cares? Who am I? myself? What do we come from? an accident. What’s a mother? an old woman. A father? the gentleman who beats her. What is crime? discovery. Virtue? opportunity. Politics? a pretext. Affection? an affectation. Morality? an affair of latitude. Punishment? this side the frontier. Reward? the other. Property? plunder. Business? other people’s money – not mine, by God! and the end of life to live till we are hanged.

Bertrand. Macaire, I came into this place with my tail between my legs already, and hungry besides; and then you get to flourishing, and it depresses me worse than the chaplain in the gaol.

Macaire. What is a chaplain? A man they pay to say what you don’t want to hear.

Bertrand. And who are you after all? and what right have you to talk like that? By what I can hear, you’ve been the best part of your life in quod; and as for me, since I’ve followed you, what sort of luck have I had? Sold again! A boose, a blue fright, two years’ hard, and the police hot-foot after us even now.

Macaire. What is life? A boose and the police.

Bertrand. Of course, I know you’re clever; I admire you down to the ground, and I’ll starve without you. But I can’t stand it, and I’m off. Good-bye: good luck to you, old man! and if you want the bundle —

Macaire. I am a gentleman of a mild disposition, and, I thank my Maker, elegant manners; but rather than be betrayed by such a thing as you are, with the courage of a hare, and the manners, by the Lord Harry, of a jumping-jack – (He shows his knife.)

Bertrand. Put it up, put it up: I’ll do what you want.

Macaire. What is obedience? fear. So march straight, or look for mischief. It’s not bon ton, I know, and far from friendly. But what is friendship? convenience. But we lose time in this amiable dalliance. Come, now, an effort of deportment: the head thrown back, a jaunty carriage of the leg; crook gracefully the elbow. Thus. ’Tis better. (Calling.) House, house here!

Bertrand. Are you mad? We haven’t a brass farthing.

Macaire. Now! – But before we leave!

SCENE IV To these, DumontDumont. Gentlemen, what can a plain man do for your service?

Macaire. My good man, in a roadside inn one cannot look for the impossible. Give one what small wine and what country fare you can produce.

Dumont. Gentlemen, you come here upon a most auspicious day, a red-letter day for me and my poor house, when all are welcome. Suffer me, with all delicacy, to inquire if you are not in somewhat narrow circumstances?

Macaire. My good creature, you are strangely in error; one is rolling in gold.

Bertrand. And very hungry.

Dumont. Dear me, and on this happy occasion I had registered a vow that every poor traveller should have his keep for nothing, and a pound in his pocket to help him on his journey.

Dumont. I will send you what we have: poor fare, perhaps, for gentlemen like you.

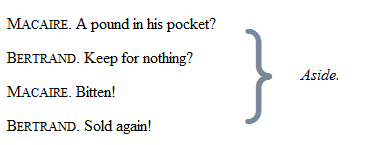

SCENE VMacaire, Bertrand; afterwards Charles, who appears on the gallery and comes downBertrand. I told you so. Why will you fly so high?

Macaire. Bertrand, don’t crush me. A pound: a fortune! With a pound to start upon – two pounds, for I’d have borrowed yours – three months from now I might have been driving in my barouche, with you behind it, Bertrand, in a tasteful livery.

Bertrand (seeing Charles). Lord, a policeman!

Macaire. Steady! What is a policeman? Justice’s blind eye. (To Charles.) I think, sir, you are in the force?

Charles. I am, sir, and it was in that character —

Macaire. Ah, sir, a fine service!

Charles. It is, sir, and if your papers —

Macaire. You become your uniform. Have you a mother? Ah, well, well!

Charles. My duty, sir —

Macaire. They tell me one Macaire – is not that his name, Bertrand? – has broken gaol at Lyons?

Charles. He has, sir, and it is precisely for that reason —

Macaire. Well, good-bye. (Shaking Charles by the hand and leading him towards the door, L.U.E.) Sweet spot, sweet spot. The scenery is… (kisses his finger-tips. Exit Charles.) And now, what is a policeman?

Bertrand. A bobby.

SCENE VIMacaire, Bertrand; to whom, Aline with tray; and afterwards MaidsAline (entering with tray and proceeding to lay table, L.). My men, you are in better luck than usual. It isn’t every day you go shares in a wedding feast.

Macaire. A wedding? Ah, and you’re the bride.

Aline. What makes you fancy that?

Macaire. Heavens, am I blind?

Aline. Well, then, I wish I was.

Macaire. I take you at the word: have me.

Aline. You will never be hanged for modesty.

Macaire. Modesty is for the poor: when one is rich and nobly born, ’tis but a clog. I love you. What is your name?

Aline. Guess again, and you’ll guess wrong. (Enter the other servants with wine baskets.) Here, set the wine down. No, that is the old Burgundy for the wedding party. These gentlemen must put up with a different bin. (Setting wine before Macaire and Bertrand, who are at table, L.)

Macaire (drinking). Vinegar, by the supreme Jove!

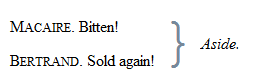

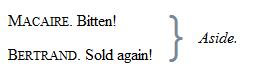

Bertrand. Sold again!

Macaire. Now, Bertrand, mark me. (Before the servants he exchanges the bottle for the one in front of Dumont’s place at the head of the other table.) Was it well done?

Bertrand. Immense.

Macaire (emptying his glass into Bertrand’s). There, Bertrand, you may finish that. Ha! music?

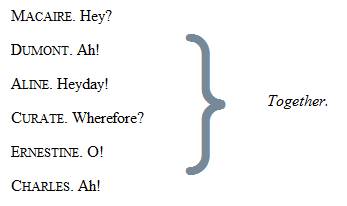

SCENE VII To these, from the inn, L.U.E., Dumont, Charles, the Curate, the Notary jigging; from the inn, R.U.E., Fiddlers playing and dancing; and through door, L.C., Goriot, Ernestine, Peasants, dancing likewise. Air: “Haste to the Wedding.” As the parties meet, the music ceasesDumont. Welcome, neighbours! welcome, friends! Ernestine, here is my Charles, no longer mine. A thousand welcomes. O, the gay day! O, the auspicious wedding! (Charles, Ernestine, Dumont, Goriot, Curate, and Notary sit to the wedding feast; Peasants, Fiddlers, and Maids, grouped at back drinking from the barrel.) O, I must have all happy around me.

Goriot. Then help the soup.

Dumont. Give me leave: I must have all happy. Shall these poor gentlemen upon a day like this drink ordinary wine? Not so; I shall drink it. (To Macaire, who is just about to fill his glass.) Don’t touch it, sir! Aline, give me that gentleman’s bottle and take him mine: with old Dumont’s compliments.

Macaire. What?

Bertrand. Change the bottle?

Dumont. Yes, all shall be happy.

Goriot. I tell ’ee, help the soup!

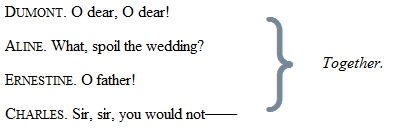

Dumont (begins to help soup. Then, dropping ladle). One word: a matter of detail; Charles is not my son. (All exclaim.) O no, he is not my son. Perhaps I should have mentioned it before.

Charles. I am not your son, sir?

Dumont. O no, far from it.

Goriot. Then who the devil’s son be he?

Dumont. O, I don’t know. It’s an odd tale, a romantic tale: it may amuse you. It was twenty years ago, when I kept the “Golden Head” at Lyons; Charles was left upon my doorstep in a covered basket, with sufficient money to support the child till he should come of age. There was no mark upon the linen, nor any clue but one: an unsigned letter from the father of the child, which he strictly charged me to preserve. It was to prove his identity; he, of course, would know the contents, and he only; so I keep it safe in the third compartment of my cash-box, with the ten thousand francs I’ve saved for his dowry. Here is the key; it’s a patent key. To-day the poor boy is twenty-one, to-morrow to be married. I did perhaps hope the father would appear; there was a Marquis coming; he wrote me for a room; I gave him the best, Number Thirteen, which you have all heard of; I did hope it might be he, for a Marquis, you know, is always genteel. But no, you see. As for me, I take all to witness I’m as innocent of him as the babe unborn.

Macaire. Ahem! I think you said the linen bore an M?

Dumont. Pardon me; the markings were cut off.

Macaire. True. The basket white, I think?

Dumont. Brown, brown.

Macaire. Ah! brown – a whitey-brown.

Goriot. I tell ’ee what, Dumont, this is all very well; but in that case, I’ll be danged if he gets my daater. (General consternation.)

Dumont. O Goriot, let’s have happy faces!

Goriot. Happy faces be danged! I want to marry my daater; I want your son. But who be this? I don’t know, and you don’t know, and he don’t know. He may be anybody; by Jarge, he may be nobody! (Exclamations.)

Curate. The situation is crepuscular.

Ernestine. Father, and Mr. Dumont (and you, too, Charles), I wish to say one word. You gave us leave to fall in love; we fell in love; and as for me, my father, I will either marry Charles or die a maid.

Charles. And you, sir, would you rob me in one day of both a father and a wife?

Dumont (weeping). Happy faces, happy faces!

Goriot. I know nothing about robbery; but she cannot marry without my consent, and that she cannot get.

Goriot (exasperated). I wun’t, and what’s more I shan’t.

Notary. I donno if I make myself clear.

Dumont. Goriot, do let’s have happy faces!

Goriot. Fudge! Fudge!! Fudge!!!

Curate. Possibly on application to this conscientious jurist, light may be obtained.

All. The Notary; yes, yes; the Notary!

Dumont. Now, how about this marriage?

Notary. Marriage is a contract, to which there are two constracting parties, John Doe and Richard Roe. I donno if I make myself clear?

Aline. Poor lamb!

Curate. Silence, my friend; you will expose yourself to misconstruction.

Macaire (taking the stage). As an entire stranger in this painful scene, will you permit a gentleman and a traveller to interject one word? There sits the young man, full, I am sure, of pleasing qualities; here the young maiden, by her own confession bashfully consenting to the match; there sits that dear old gentleman, a lover of bright faces like myself, his own now dimmed with sorrow; and here Р(may I be allowed to add?) Рhere sits this noble Roman, a father like myself, and like myself the slave of duty. Last you have me РBaron Henri-Fr̩d̩ric de Latour de Main de la Tonnerre de Brest, the man of the world and the man of delicacy. I find you all Рpermit me the expression Рgravelled. A marriage and an obstacle. Now, what is marriage? The union of two souls, and, what is possibly more romantic, the fusion of two dowries. What is an obstacle? the devil. And this obstacle? to me, as a man of family, the obstacle seems grave; but to me, as a man and a brother, what is it but a word? O my friend (to Goriot), you whom I single out as the victim of the same noble failings with myself of pride of birth, of pride of honesty РO my friend, reflect. Go now apart with your dishevelled daughter, your tearful son-in-law, and let their plaints constrain you. Believe me, when you come to die, you will recall with pride this amiable weakness.

Goriot. I shan’t, and what’s more I wun’t. (Charles and Ernestine lead him up stage, protesting. All rise except Notary.)

Dumont (front R., shaking hands with Macaire). Sir, you have a noble nature. (Macaire picks his pocket.) Dear, me, dear me, and you are rich.

Macaire. I own, sir, I deceived you: I feared some wounding offer, and my pride replied. But to be quite frank with you, you behold me here, the Baron Henri-Frédéric de Latour de Main de la Tonnerre de Brest, and between my simple manhood and the infinite, these rags are all.

Dumont. Dear me, and with this noble pride, my gratitude is useless. For I, too, have delicacy. I understand you could not stoop to take a gift.

Macaire. A gift? a small one? never!

Dumont. And I will never wound you by the offer.

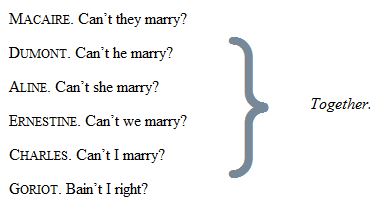

Goriot (taking the stage). But, look ’ee here, he can’t marry.

Goriot. Not without his veyther’s consent! And he hasn’t got it; and what’s more, he can’t get it: and what’s more, he hasn’t got a veyther to get it from. It’s the law of France.

Aline. Then the law of France ought to be ashamed of itself.

Ernestine. O, couldn’t we ask the Notary again?

Curate. Indubitably you may ask him.

Notary. Constracting parties.

Curate. Possibly to-morrow at an early hour he may be more perspicuous.

Goriot. Ay, before he’ve time to get at it.

Notary. Unoffending jurisconsult overtaken by sorrow. Possibly by applying justice of peace might afford relief.

Goriot. I’ll go. I don’t mind getting advice, but I wun’t take it.

Macaire. My friends, one word: I perceive by your downcast looks that you have not recognised the true nature of your responsibility as citizens of time. What is care? impiety. Joy? the whole duty of man. Here is an opportunity of duty it were sinful to forego. With a word, I could lighten your hearts; but I prefer to quicken your heels, and send you forth on your ingenuous errand with happy faces and smiling thoughts, the physicians of your own recovery. Fiddlers, to your catgut! Up, Bertrand, and show them how one foots it in society; forward, girls, and choose me every one the lad she loves; Dumont, benign old man, lead forth our blushing Curate; and you, O bride, embrace the uniform of your beloved, and help us dance in your wedding-day. (Dance, in the course of which Macaire picks Dumont’s pocket of his keys, selects the key of the cash-box, and returns the others to his pocket. In the end, all dance out; the wedding-party, headed by Fiddlers, L.C.; the Maids and Aline into the inn, R.U.E. Manet, Bertrand and Macaire.)

SCENE VIIIMacaire, Bertrand, who instantly takes a bottle from the wedding-table, and sits with it, LMacaire. Bertrand, there’s a devil of a want of a father here.

Bertrand. Ay, if we only knew where to find him.

Macaire. Bertrand, look at me: I am Macaire; I am that father.

Bertrand. You, Macaire? – you a father?

Macaire. Not yet, but in five minutes. I am capable of anything. (Producing key.) What think you of this?

Bertrand. That? Is it a key?

Macaire. Ay, boy, and what besides? my diploma of respectability, my patent of fatherhood. I prigged it – in the ardour of the dance I prigged it; I change it beyond recognition, thus (twists the handle of the key); and now…? Where is my long-lost child? produce my young policeman, show me my gallant boy.

Bertrand. I don’t understand.

Macaire. Dear innocence, how should you? Your brains are in your fists. Go and keep watch. (He goes into the office and returns with the cash-box.) Keep watch, I say.

Bertrand. Where?

Macaire. Everywhere. (He opens box.)

Bertrand. Gold.

Macaire. Hands off! Keep watch. (Bertrand at back of stage.) Beat slower, my paternal heart! The third compartment! let me see.

Bertrand. S’st! (Macaire shuts box.) No: false alarm.

Macaire. The third compartment. Ay, here t —

Bertrand. S’st! (Same business.) No: fire away.

Macaire. The third compartment: it must be this.

Bertrand. S’st. (Macaire keeps box open, watching Bertrand.) All serene: it’s the wind.

Macaire. Now, see here! (He darts his knife into the stage.) I will either be backed as a man should be, or from this minute out I’ll work alone. Do you understand? I said alone.

Bertrand. For the Lord’s sake, Macaire! —

Macaire. Ay, here it is. (Reading letter.) “Preserve this letter secretly; its terms are known only to you and me; hence when the time comes, I shall repeat them, and my son will recognise his father.” Signed: “Your Unknown Benefactor.” (He hums it over twice and replaces it. Then, fingering the gold.) Gold! The yellow enchantress, happiness ready-made and laughing in my face! Gold: what is gold? The world; the term of ills; the empery of all; the multitudinous babble of the ’Change, the sailing from all ports of freighted argosies; music, wine, a palace; the doors of the bright theatre, the key of consciences, and – love’s – love’s whistle! All this below my itching fingers; and to set this by, turn a deaf ear upon the siren present, and condescend once more, naked, into the ring with fortune – Macaire, how few would do it! But you, Macaire, you are compacted of more subtile clay. No cheap immediate pilfering: no retail trade of petty larceny; but swoop at the heart of the position, and clutch all!

Bertrand (at his shoulder). Halves!

Macaire. Halves? (He locks the box.) Bertrand, I am a father. (Replaces box in office.)

Bertrand (looking after him). Well, I – am – damned!

DROPACT II

When the curtain rises, the night has come. A hanging cluster of lighted lamps over each table, R. and L. Macaire, R., smoking a cigarette; Bertrand, L., with a churchwarden: each with bottle and glass

SCENE IMacaire, BertrandMacaire. Bertrand, I am content: a child might play with me. Does your pipe draw well?

Bertrand. Like a factory chimney. This is my notion of life: liquor, a chair, a table to put my feet on, a fine clean pipe, and no police.

Macaire. Bertrand, do you see these changing exhalations do you see these blue rings and spirals, weaving their dance, like a round of fairies, on the footless air?

Bertrand. I see ’em right enough.

Macaire. Man of little vision, expound me these meteors! What do they signify, O wooden-head? Clod, of what do they consist?

Bertrand. Damned bad tobacco.

Macaire. I will give you a little course of science. Everything, Bertrand (much as it may surprise you), has three states: a vapour, a liquid, a solid. These are fortune in the vapour: these are ideas. What are ideas? the protoplasm of wealth. To your head – which, by the way, is solid, Bertrand – what are they but foul air? To mine, to my prehensile and constructive intellects, see, as I grasp and work them, to what lineaments of the future they transform themselves: a palace, a barouche, a pair of luminous footmen, plate, wine, respect, and to be honest!

Bertrand. But what’s the sense in honesty?

Macaire. The sense? You see me: Macaire: elegant, immoral, invincible in cunning; well, Bertrand, much as it may surprise you, I am simply damned by my dishonesty.

Bertrand. No!

Macaire. The honest man, Bertrand, that’s God’s noblest work. He carries the bag, my boy. Would you have me define honesty? the strategic point for theft. Bertrand, if I’d three hundred a year, I’d be honest to-morrow.

Bertrand. Ah! don’t you wish you may get it!

Macaire. Bertrand, I will bet you my head against your own – the longest odds I can imagine – that with honesty for my spring-board, I leap through history like a paper hoop, and come out among posterity heroic and immortal.

SCENE IITo these, all the former characters, less the Notary. The fiddles are heard without playing dolefully. Air: “O dear, what can the matter be?” in time to which the procession enters

Macaire. Well, friends, what cheer?

Curate. The facts have justified the worst anticipations of our absent friend, the Notary.

Macaire. I perceive I must reveal myself.

Dumont. God bless me, no!

Macaire. My friends, I had meant to preserve a strict incognito, for I was ashamed (I own it!) of this poor accoutrement; but when I see a face that I can render happy, say, my old Dumont, should I hesitate to work the change? Hear me, then, and you (to the others) prepare a smiling countenance. (Repeating.) “Preserve this letter secretly; its terms are known only to you and me: hence when the time comes, I shall repeat them, and my son will recognise his father. – Your Unknown Benefactor.”

Dumont. The words! the letter! Charles, alas! it is your father!