полная версия

полная версияThe Restless Sex

All the resolute composure she could summon did not conceal from him the tragedy of a child who is about to lose its hero and who feels itself left out – excluded, as it were, from the last sad rites.

He was touched, conscience stricken, and yet almost inclined to smile. He said casually, as they rose from the table:

"Steve, dear, tell Janet to make you ready at once, if you are going to see Jim off."

"Am —I– going!" faltered the child, flushing and tremulous with surprise and happiness.

"Why, of course. Run quickly to Janet, now." And, to his son, when the eager little flying feet had sped out of sight and hearing: "Steve felt left out, Jim. Do you understand, dear?"

"Y-yes, Father."

"Also, she is inclined to take your departure very seriously. You do understand, don't you, my dear son?"

The boy said that he did, vaguely disappointed that he was not to have the last moments alone with his father.

So they all went down town together in the car, and there were other boys there with parents; and some recognitions among the other people; desultory, perfunctory conversations, cohesion among the school boys welcoming one another with ardour and strenuous cordiality after only ten days' separation.

Chiltern Grismer, father of Oswald, came over and spoke to Cleland Senior:

"Our respective sons, it appears, so far forgot their Christian principles as to indulge in a personal encounter in school," he said in a pained voice. "Hadn't they better shake hands, Cleland?"

"Certainly," replied John Cleland. "If a fight doesn't clean off the slate, there's something very wrong somewhere … Jim?"

Cleland Junior left the group of gossiping boys; young Grismer, also, at his father's summons, came sauntering nonchalantly over from another group.

"Make it up with young Cleland!" said Chiltern Grismer, tersely. "Mr. Cleland and I are friends of many years. Let there be no dissension between our sons."

"Offer your hand, Jim," added Cleland Senior. "A punch in the nose settles a multitude of sins; doesn't it, Grismer?"

The ceremony was effected reluctantly, and in anything but a cordial manner. Stephanie, looking on, perplexed, caught young Grismer's amber-coloured eyes fixed on her; saw the tall, sandy-haired boy turn to look at her as he moved away to rejoin his particular group; saw the colour rising in his mischievous face when she surprised him peeping at her again over another boy's shoulder.

Several times, before the train left, the little girl became conscious that this overgrown, sandy-haired boy was watching her, sometimes with frankly flattering admiration, sometimes furtively, as though in sly curiosity.

"Who is that kid?" she distinctly heard him say to another boy. She calmly turned her back.

And was presently aware of the elder Grismer's expressionless gaze concentrated upon herself.

"Is this the little girl?" he said to Cleland Senior in his hard, dry voice.

"That is my little daughter, Stephanie," replied Cleland coldly, discouraging any possible advances on Grismer's part. For there would never be any reason for bringing Stephanie in contact with the Grismers; and there might be reasons for keeping her ignorant of their existence. Which ought to be a simple matter, because he never saw Grismer, except when he chanced to encounter him quite casually here and there in town.

"She's older than I supposed," remarked Grismer, staring steadily at her, where she stood beside Jim, shyly conversing with a group of his particular cronies. Boy-like, they all were bragging noisily for her exclusive benefit, talking school-talk, and swaggering and showing off quite harmlessly as is the nature of the animal at that age.

"I don't observe any family resemblance," mused Grismer, pursing his slit-like lips.

"No?" inquired Cleland drily.

"No, none whatever. Of course, the connection is remote – m-m-m'yes, quite remote. I trust," he added magnanimously, "that you will be able to render her life comfortable and pleasant; and that the stipend you purpose to bestow upon her may, if wisely administered, keep her from want."

Cleland, who was getting madder every moment, turned very red now.

"I think," he said, managing to control his temper, "that it will scarcely be a question of want with Stephanie Quest. What troubles me a little is that she's more than likely to be an heiress."

"What!"

"It looks that way."

"Do you – do you mean, Cleland, that – that any legal steps to re-open – "

"Good Lord, no!" exclaimed Grismer, contemptuously. "She wouldn't touch a penny of Grismer money – not a penny! I wouldn't lift a finger to stir up that mess again, even if it meant a million for her!"

Grismer breathed more easily, though Cleland's frank and unconcealed scorn left a slight red on his parchment-like skin.

"Our conception of moral and spiritual responsibility differs, I fear," he said, " – as widely as our creeds differ. I regret that my friend of many years should appear to be a trifle biassed – m-m-m'yes, a trifle biassed in his opinion – "

"It's none of my affair, Grismer. We're different, that's all. You had, perhaps, a legal right to your unhappy sister's share of the Grismer inheritance. You exercised it; I should not have done so. It's a matter of conscience – to put it pleasantly."

"It is a matter of creed," said Grismer grimly. "It was God's will."

Cleland shrugged.

"Let it go at that. Anyway, you needn't worry over any possible action that might be brought against you or your heirs. There won't be any. What I meant was that the child's aunt, Miss Rosalinda Quest, seems determined to leave little Stephanie a great deal more money than is good for anybody. It isn't necessary. I don't believe in fortunes. I'm wary of them, afraid of them. They change people – often change their very natures. I've seen it too many times – observed the undesirable change in people who were quite all right before they came into fortunes. No; I am able to provide for her amply; I have done so. That ought to be enough."

Grismer's dry, thin lips remained parted; he scarcely breathed; and his remarkable eyes continued to bore into Cleland with an intensity almost savage.

Finally he said, in a voice so dry that it seemed to crackle:

"This is – amazing. I understood that the family had cast out and utterly disowned the family of Harry Quest – m-m-m'yes, turned him out completely – him and his. So you will pardon my surprise, Cleland… Is – ah – the Quest fortune – as it were – considerable?"

"Several millions, I believe," replied Cleland carelessly, moving away to rejoin his son and Stephanie, where they stood amid the noisy, laughing knot of school-boys.

Grismer looked after him, and his face, which had become drawn, grew almost ghastly. So this was it! Cleland had fooled him. Cleland, with previous knowledge of what this aunt was going to do for the child, had cunningly selected her for adoption – doubtless designed her, ultimately, for his son. Cleland had known this; had kept the knowledge from him. And that was the reason for all this philanthropy. Presently he summoned his son, Oswald, with a fierce gesture of his hooked forefinger.

The boy detached himself leisurely from his group of school-fellows and strolled up to his father.

"Don't quarrel with young Cleland again. Do you hear?" he said harshly.

"Well, I – "

"Do you hear? – you little fool!"

"Yes, sir, but – "

"Be silent and obey! Do as I order you. Seek his friendship. And, if opportunity offers, become friends with that little girl. If you don't do as I say, I'll cut your allowance. Understand me, I want you to be good friends with that little girl!"

Oswald cast a mischievous but receptive glance toward Stephanie.

"I'll sure be friends with her, if I have a show," he said. "She's easily the prettiest kid I ever saw. But Jim doesn't seem very anxious to introduce me. Maybe next term – " He shrugged, but regarded Stephanie with wistful golden eyes.

After the gates were opened, and when at last the school boys had departed and the train was gone, Stephanie remained tragically preoccupied with her personal loss in the departure of Cleland Junior. For he was the first boy she had ever known; and she worshipped him with all the long-pent ardour of a lonely heart.

Memory of the sandy youth with golden eyes continued in abeyance, although he had impressed her. It had, in fact, been a new experience for her to be noticed by an older boy; and, although she considered young Grismer homely and a trifle insolent, there remained in her embryonic feminine consciousness the grateful aroma of incense swung before her – incense not acceptable, but still unmistakably incense – the subtle flattery of man.

As for young Grismer, reconciliation between him and Jim having been as pleasantly effected as the forcible feeding of a jailed lady on a hunger strike, he sauntered up to Cleland Junior in the car reserved for Saint James School, and said amiably:

"Who was the little peach you kissed good-bye, Jim?"

The boy's clear brown eyes narrowed just a trifle.

"She's – my – sister," he drawled. "What about it?"

"She's so pretty – for a kid – that's all."

Jim, eyeing him menacingly, replied in the horrid vernacular:

"That's no sty on your eye, is it?"

"F'r heaven's sake!" protested Grismer. "Are you still carrying that old chip on your shoulder? I thought it was all squared."

Jim considered him for a few moments.

"All right," he said; "it's squared, Oswald… Only, somehow I can't get over feeling that there are some more fights ahead of us… Have a caramel?"

Chiltern Grismer joined Cleland Senior on the way to the street, and they strolled together toward the station entrance. Stephanie walked in silence beside Cleland, holding rather tightly to his arm, not even noticing Grismer, and quite overwhelmed by her own bereavement.

Grismer murmured in his dry, guarded voice:

"She's pretty enough and nicely enough behaved to be your own daughter."

Cleland nodded; a deeper flush of annoyance spread over his handsome, sanguine face. He resented it when people did not take Stephanie for his own flesh and blood; and it even annoyed him that Grismer should mention a matter upon which he had become oddly sensitive.

"I hope you won't ever be sorry, Cleland," remarked the other in his dry, metallic voice. "Yes, indeed, I hope you won't regret your philanthropic venture."

"I am very happy in my little daughter," replied Cleland quietly.

"She's turning out quite satisfactory?"

"Of course!" snapped the other.

"M-m-m!" mused Grismer between thin, dry lips. "It's rather too early to be sure, Cleland. You never can tell what traits are going to reveal themselves in the young. There's no knowing what may crop out in them. No – no telling; no telling. Of course, sometimes they turn out well. M-m-m'yes, quite well. That's our experience in the Charities Association. But, more often, they – don't! – to be perfectly frank with you – they don't turn out very well."

Cleland's features had grown alarmingly red.

"I'm not apprehensive," he managed to say.

"Oh, no, of course, it's no use worrying. Time will show. M-m-m! Yes. It will all be made manifest in time. M-m-m'yes! Time'll show, Cleland – time'll show. But – I knew my sister," he added sadly, "and I am afraid – very much afraid."

At the entrance for motors they parted. Grismer got into a shabby limousine driven by an unkempt chauffeur.

"Going my way, Cleland?"

"Thanks, I have my car."

"In that case," returned Grismer, "I shall take my leave of you. Good-bye, and God be with you," he said piously. "And good-bye to you, my pretty little miss," he added graciously, distorting his parchment features into something resembling a smile. "Tell your papa to bring you to see me sometime when my boy is home from school; and," he added rather vaguely, "we'll have a nice time and play games. Good-bye!"

"Who was that man, Daddy?" asked Stephanie, as their own smart little car drew up.

"Oh, nobody – just a man with whom I have a – a sort of acquaintance," replied Cleland.

"Was that his boy who kept looking at me all the while in the station, Daddy?"

"I didn't notice. Come, dear, jump in."

So he took Stephanie back to the house where instruction in the three R's awaited her, with various extras and embellishments suitable for the education of the daughter of John William Cleland.

The child crept up close to him in the car, holding tightly to his arm with both of hers.

"I'm lonely for Jim," she whispered. "I – " but speech left her suddenly in the lurch.

"You're going to make me proud of you, darling; aren't you?" he murmured, looking down at her.

The child merely nodded. Grief for the going of her first boy had now left her utterly dumb.

CHAPTER VII

There is a serio-comic, yet charming, sort of tragedy – fortunately only temporary – in the attachment of a little girl for an older boy. It often bores him so; and she is so daintily in earnest.

The one adores, tags after, and often annoys; the other, if chivalrous, submits.

It began this way between Stephanie Quest and Jim Cleland. It continued. She realized with awe the discrepancy in their ages; he was amiable enough to pretend to waive the discrepancy. And his condescension almost killed her.

The poor child grew older as fast as she possibly could; resolute, determined to overtake him somewhere, if that could be done. For in spite of arithmetic she seemed to know that it was possible. Moreover, it was wholly characteristic of her to attack with pathetic confidence the impossible – to lead herself as a forlorn hope and with cheerful and reckless resolution into the most hopeless impasse.

Cleland Senior began to notice this trait in her – began to wonder whether it was an admirable trait or a light-headed one.

Once, an imbecile canary, purchased by him for her, and passionately cherished, got out of its open cage, out of the open nursery window, and perched on a cornice over one of the windows. And out of the window climbed Stephanie, never hesitating, disregarding consequences, clinging like a desperate kitten to sill and blind, negotiating precarious ledges with steady feet; and the flag-stones of the area four stories below her, and spikes on the iron railing.

A neighbour opposite fainted; another shouted incoherently. It became a hair-raising situation; she could neither advance nor retreat. The desperate, Irish keening of Janet brought Meacham; Meacham, at the telephone, notified the nearest police station, and a section of the Fire Department. The latter arrived with extension ladders.

It was only when pushed violently bed-ward, as punishment, that the child realized there had been anything to be frightened about. Then she became scared; and was tearfully glad to see Cleland when he came in that evening from a print-hunting expedition.

And once, promenading on Fifth Avenue with Janet, for the sake of her health – such being the régime established – she separated two violently fighting school-boys, slapped the large one, who had done the bullying, soundly, cuffed another, who had been enjoying the unequal combat, fell upon a fourth, and was finally hustled home with her expensive clothing ruined. But in her eyes and cheeks still lingered the brilliant fires of battle, when Janet stripped her for a bath.

And once in the park she sprang like a young tigress upon a group of ragamuffins who had found a wild black mallard duck, nesting in a thicket near the lake, and who were stoning the frightened thing.

All Janet could see was a most dreadful melée agitating the bushes, from which presently burst boy after boy, in an agony of flight, rushing headlong and terror-stricken from that dreadful place where a wild-girl raged, determined on their extermination.

Stephanie's development was watched with tender, half-fearful curiosity by Cleland.

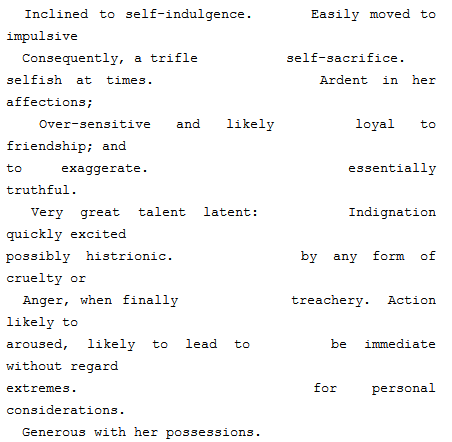

As usual, two separate columns were necessary to record the varied traits so far apparent in her. These traits Cleland noted in the book devoted to memoranda concerning the child, writing them as follows:

So far he could discover nothing vicious in her, no unworthy inherited instincts beyond those common to young humans, instincts supposed to be extirpated by education.

She was no greedier than any other healthy child, no more self-centred; all her appetites were normal, all her inclinations natural. She had a good mind, but a very human one, fairly balanced but sensitive to emotion, inclination, and impulse, and sometimes rather tardy in readjusting itself when logic and reason were required to regain equilibrium.

But the child was more easily swayed by gratitude than by any other of the several human instincts known as virtues.

So she grew toward adolescence, closely watched by Cleland, good-naturedly tolerated by Jim, worshipped by Janet, served by Meacham with instinctive devotion – the only quality in him not burnt out in his little journeys through hell.

There were others, too, in the world, who remembered the child. There was her aunt, who came once a month and brought always an expensive present, over the suitability of which she and Cleland differed to the verge of rudeness. But they always parted on excellent terms. And there was Chiltern Grismer, who sat sometimes for hours in his office, thinking about the child and the fortune which threatened her.

Weeks, adhering to one another, became months; months totalled years – several of them, recorded so suddenly that John Cleland could not believe it.

He had arrived at that epoch in the life of man when the years stood still with him: when he neither felt himself changing nor appeared to grow older, though all around him he was constantly aware of others aging. Yet, being always with Stephanie, he could not notice her rapid development, as he noted the astonishing growth of his son when the boy came home after brief absences at school.

Stephanie, still a child, was becoming something else very rapidly. But still she remained childlike enough to idolize Jim Cleland and to show it, without reserve. And though he really found her excellent company, amusing and diverting, her somewhat persistent and dog-like devotion embarrassed and bored him sometimes. He was at that age.

Young Grismer, in Jim's hearing, commenting upon a similar devotion inflicted on himself by a girl, characterized her as "too damn pleasant" – a brutal yet graphic summary.

And for a while the offensive phrase stuck in Jim's memory, though always chivalrously repudiated as applying to Stephanie. Yet, the poor girl certainly bored him at times, so blind her devotion, so pitiful her desire to please, so eager her heart of a child for the comradeship denied her in the dreadful years of solitude and fear.

For a year or two the affair lay that way between these two; the school-boy's interest in the little girl was the interest of polite responsibility; consideration for misfortune, toleration for her sex, with added allowance for her extreme youth. This was the boy's attitude.

Had not boarding-school and college limited his sojourn at home, it is possible that indifference might have germinated.

But he saw her so infrequently and for such short periods; and even during the summer vacation, growing outside interests, increasing complexity in social relations with fellow students – invitations to house parties, motor trips, camping trips – so interrupted the placid continuity of his vacation in their pleasant summer home in the northern Berkshires, that he never quite realized that Stephanie Quest was really anything more than a sort of permanent guest, billeted indefinitely under his father's roof.

When he was home in New York at Christmas and Easter, his gravely detached attitude of amiable consideration never varied toward her.

The few weeks at a time that he spent at "Runner's Rest," his father's quaint and ancient place on Cold River, permitted him no time to realize the importance and permanency of the place she already occupied as an integral part of the house of Cleland.

A thousand new interests, new thoughts, possessed the boy in the full tide of adolescence. All the world was beginning to unclose before him like the brilliant, fragrant petals of a magic flower. And in this rainbow transformation of things terrestrial, a boy's mind is always unbalanced by the bewildering and charming confusion of it all – for it is he who is changing, not the world; he is merely learning to see instead of to look, to comprehend instead of to perceive, to realize instead of to take for granted all the wonders and marvels and mysteries to which a young man is heir.

It is drama, comedy, farce, tragedy, this inevitable awakening; it is the alternate elucidation and deepening of mysteries; it is a day of clear, keen reasoning succeeding a day of illogical caprice; an hour aquiver with undreamed-of mental torture followed by an hour of spiritual exaltation; it is the era of magnificent aspiration, of inexplicable fear, of lofty abnegations, of fierce egotisms, of dreams and of convictions, of faiths for which youth dies; and, alas, it is a day of pitiless development which leaves the shadowy memory of faith lingering in the brain, and, on the lips, a smile.

And, amid such emotions, such impulses, such desires, fears, aspirations, hopes, regrets, the average boy puts on that Nessus coat called manhood. And he has, in his temporarily dislocated and unadjusted brain, neither the time nor the patience, nor the interest, nor the logic at his command necessary to see and understand what is happening under his aspiring and heavenward-tilted nose. Only the clouds enrapture him; where every star beckons him he responds in a passion of endeavour.

And so he begins the inevitable climb toward the moon – the path which every man born upon the earth has trodden far or only a little way, but the path all men at least have tried.

In his freshman year at Harvard, he got drunk. The episode was quite inadvertent on his part – one of those accidents incident to the vile, claret-coloured "punches" offered by some young idiot in "honour" of his own birthday.

The Cambridge police sheltered him over night; his fine was over-subscribed; he explored the depths of hell in consequence of the affair, endured the agony of shame, remorse, and self-loathing to the physical and mental limit, and eventually recovered, regarding himself as a reformed criminal with a shattered past.

However, the youthful gloom and melancholy dignity with which this clothed him had a faint and not entirely unpleasant flavour – as one who might say, "I have lived and learned. There is the sad wisdom of worldly things within me." But he cut out alcohol. It being the fashion at that time to shrug away an offered cup, he found little difficulty in avoiding it.

In his Sophomore year, he met the inevitable young person. And, after all that had been told him, all that he had disdainfully pictured to himself, did not recognize her when he met her.

It was one of those episodes which may end any way. And it ended, of course, in one way or another. But it did end.

Thus the limited world he moved in began to wear away the soft-rounded contours of boyhood; he learned a little about men, nothing whatever about women, but was inclined to consider that he understood them sadly and perfectly. He wrote several plays, novels and poems to amuse himself; wrote articles for the college periodicals, when he was not too busy training with the baseball squad or playing tennis, or lounging through those golden and enchanted hours when the smoke of undergraduate pipes spins a magic haze over life, enveloping books and comrades in that exquisite and softly brilliant web which never tears, never fades in memory while life endures.

He made many friends; he visited many homes; he failed sometimes, but more often he made good in whatever he endeavoured.

His father came on to Cambridge several times – always when his son requested it – and he knew the sympathy of his father in days of triumph, and he understood his father's unshaken belief in his only son when that son, for the moment, faltered.