полная версия

полная версияThe Third Officer: A Present-day Pirate Story

Burgoyne was not likely to fail through lack of precaution or by neglecting to take proper steps to facilitate his return.

The cave exceeded the Third Officer's expectations. It was for the most part dry, the floor being above high-water mark, and the undisturbed sand at its mouth pointed to the fact that a long time had elapsed since human feet had trodden it. Darkness prevented a minute examination, and it was only by a sense of touch that the two men were able to make their investigations.

About eighty feet in length, and with a gradually shelving floor, the cave was less than five feet in height at its entrance, but soon increased until Minalto was unable to touch the roof even with his enormous reach. In width it averaged about twelve feet when half a dozen paces inside its mouth.

There was water, too. Eagerly Burgoyne groped for and found the steady trickle. Holding his hands cup-fashion he filled his palms with water and held the liquid to his lips.

"Fresh!" he exclaimed to his companion. "We're in luck this time."

"But we've nothin' in the barrel line for tu put et in," added Jasper.

"Not even a petrol tin," added Alwyn. "Ever drunk water out of a petrol tin, Minalto?"

The Scilly Islander shook his head.

"Leave ut tu you, sir," he replied. "I've a-drunk water wi' three inches o' paraffin on top of ut on the West Coast – Accra way. That wur enough for I."

Gently jerking the rope, as a signal to Branscombe for the stock of emergency rations to be sent down, Burgoyne gave his companion instructions to bury the stuff in the cave. Leaving Minalto to carry on, the Third Officer walked down to the water's edge, then, turning abruptly to the left, followed the line of wet sand left by the receding tide.

At every possible spot where the cliff might be scalable he approached the base of the rocks, always without the desired result. Carefully obliterating his footprints on the dry sand, he continued his way until farther progress was barred by the abrupt ending of the beach at a point beyond which the cliff rose sheer from the lagoon.

The secret base was an unscalable plateau with only one approach – except by means of a rope – and that was the carefully-guarded tunnel, where more than likely (although Burgoyne was not certain on that point) the double portcullis was lowered every night.

Disappointed but by no means disheartened Burgoyne returned to the cave, where Jasper had completed his task and was awaiting him. To him Alwyn related the results of his investigations.

"Lawks!" exclaimed Minalto. "You can swim, can't you, sir? What's wrong with the reef? Can't us swim off to 'en and walk round to t' harbour? I'd do it now, on my head like, if you're in no particular hurry."

"Sharks?" queried Alwyn.

"Sharks!" repeated Jasper. "Ain't seen none since I've bin on the island, an' many's the time I've watched the water an' within' I could have a swim. What d'ye say, sir. Might I go?"

Burgoyne was fired by the man's enthusiasm. It was now midnight. Allowing three hours to cover a distance of six or seven miles, Minalto ought with luck to be back well before four. This would give the party an hour and a half before dawn in which to "pack up", replace gear, remove all traces of the night's work, and regain their quarters.

"All right," agreed the Third Officer. "I'll come with you as far as the end of the bay. Wish I could do the whole thing, only the others would be scared stiff and think we'd done ourselves in. When I return I'll get myself hauled up and wait on the top of the cliff. You know the signal? Right, and don't forget to wipe out your footprints. The tide will be at quarter flood on your return."

With many other cautions and suggestions, Burgoyne accompanied the stout-hearted seaman to a spot where the reef approached to within three hundred yards of the shore.

Taking off his shoes, and slinging them round his neck, Minalto waded waist-deep into the water and struck out for the line of milk-white foam that marked the reef. Burgoyne remained at the edge of the lagoon until the phosphorescent swirl that marked the swimmer's progress was merged into the darkness. He had no indication that Minalto had reached the reef, for his white-clad form would be indistinguishable against the ever-breaking wall of foam.

Retracing his way to the cave Burgoyne slipped into the bowline and tugged three times at the rope. The signal was promptly answered, and the swaying, roundabout ascent commenced.

"Well?" inquired Branscombe anxiously, when Alwyn landed safely on the top of the cliff.

"All serene," replied the Third Officer, a little breathlessly. "We'll have to stand by for a few hours. Minalto has gone on a voyage of exploration. That chap gave me a thundering good idea. I was getting a bit tied up in knots when I found there was no way up from the beach, so he suggested walking along the reef – and he's gone and done it," he added vernacularly.

Dispatching Twill to inform Captain Blair of the alteration of plans, so that the Old Man would not be unduly anxious about their failure to return at the suggested time, the three officers prepared to make the best of their long vigil. They took fifteen minutes' shifts to tend the rope, so that should Minalto return before they expected there would be no delay in receiving his signal and hauling him up.

"Can you get hold of another length of signal halyard, Phil?" asked Alwyn. "Another three hundred feet of it."

"I dare say," replied Branscombe. "I'll have a jolly good shot at getting it, anyway. What's the scheme?"

Burgoyne rubbed his aching shoulders.

"If you'd been barged into the cliff umpteen times, old son, you'd know," he declared grimly. "We want a guide-line, stretched taut and about eighteen inches inside the rope. That'll prevent anyone being bumped, and also spare them the luxury of an impromptu merry-go-round. We'll have to lower Young Bill, and we may as well make things as comfortable as possible for her."

"Quite so," agreed Phil. "I'll get some line tomorrow, even if it makes my figure look like that of a portly alderman. It wouldn't be a bad idea either to get hold of some spare canvas. You'll want some sort of awning or tent for the boat, and it will come in handy. For one thing, we can wrap Miss Vivian up in it when we lower her."

"What for?" asked Withers.

"To protect her in case any loose stones fall from the cliff," explained Branscombe. "'Sides, if she's covered up she won't be quite so frightened when she's being lowered. At least, I shouldn't think so."

For some minutes silence reigned, save for the ever-present dull rumble of the surf. Then Withers apparently without any reason, began chuckling to himself.

"What is it?" asked Phil.

"What's the joke," added Alwyn. "Out with it."

"Nothing much," replied Withers. "Only a reminiscence. This cliff recalled it."

He paused, his eyes fixed seaward.

"Let's have it, old son," prompted Branscombe.

"I thought I saw a vessel's masthead light out there," declared the Second Engineer. "Must have been mistaken… The yarn? Oh, it was merely an incident. It was in '14, just after war broke out. I was on a collier awaiting orders at Whitby. Everyone was on thorns over the spy scare. Well, one night, there was a report that lights were flashing on the cliff, and a crowd of fellows went off to investigate. Having nothing better to do that evening, I went too. Sure enough there were lights about every half minute. About two miles from Whitby we ran full tilt into a couple of men striking matches, so they were promptly collared."

The narrator paused and looked seaward again.

"What happened?" asked Burgoyne.

"Nothing – they were released," replied Withers.

"I can't see anything funny in that," remarked Phil.

"Well, it was funny – and pathetic, too," explained Withers. "They were deaf mutes. One lived in a small cottage near Kettleness, and the other's home was in York. They had missed the last train for Kettleness and were walking along the cliff path to Whitby. Their only means of communicating with each other was by lip-reading, and since it was dark they stopped and struck matches whenever they wanted to converse. They had used up three boxes of matches by the time we came up. Poor blighters! As likely as not they didn't know there was a war on; if they did it was obvious they hadn't heard about the regulations concerning coastwise lights. But, by Jove! surely those are vessel's steaming lights?"

"It is, by smoke!" exclaimed Burgoyne. "A steamer going south. I can just distinguish her port light."

"The Malfilio perhaps?" suggested Branscombe.

"Not she," declared Withers. "That steam pipe of hers will take at least two days more before it's patched up."

"I can see her green, now," announced Alwyn "She's altering course. If she holds on she'll pile herself upon the reef."

Helpless to warn the on-coming vessel – for even had the three officers been provided with means of signalling they would have incurred heavy penalties by the pirates and the wrecking of all the formers' carefully laid plans – the watchers on the cliff awaited events.

The vessel was now steaming dead slow – at least she took an unconscionable time in approaching. That was in her favour. It might give the look-outs the opportunity to hear the roar of the surf; while, even if she did strike, and were held by the coral reef, she would not be likely to sustain serious damage.

Suddenly a dazzling glare leapt from the vessel and the giant beam of a searchlight swept the island. From where the three officers lay prone on the grass they could see the rim of the cliff outlined in silver. The crest of the Observation Hill was bathed in the electric gleams, but elsewhere, owing to the depression towards the centre of the plateau, the island was in darkness. So carefully chosen was the site of the various buildings that nowhere from seaward could they be visible.

"A warship!" declared Burgoyne. "I say, this complicates matters. Let's get back to the huts, or we'll be missed. We can return before dawn."

Cautiously the three officers made their way down the slight slope, where the darkness, by contrast with the slowly traversing beam of light overhead, was intense.

When within fifty yards of the nearest of the prisoners' huts Burgoyne gripped his companions' arms.

"Lie down!" he whispered.

Both officers obeyed promptly. Alwyn, on hands and knees, went on. Presently he rejoined them.

"It's too late," he said in a low voice. "There is an armed pirate outside every hut."

CHAPTER XV

How Minalto Fared

Burgoyne and his companions were on the horns of a dilemma. If they persisted in their attempt to regain their quarters they would almost certainly be detected, while even if they succeeded they would be unable to return to the cliff. Minalto would have to be left to take his chance, and the gaunt evidence of the night's work would be laid bare with the dawn. If they returned to the cliff there was the possibility that they would have to hide all next day, and be faced with the awkward problem of explaining their absence satisfactorily.

They chose the latter course, and upon returning to the scene of the lowering operations they flung themselves flat upon the turf, lest their silhouettes would betray them to the pirates stationed about the camp and concealed in the bushes on the summit of Observation Hill.

There they lay, hardly daring to stir a limb and maintaining absolute silence for the best part of an hour. Then the searchlight, which had been playing continuously upon the island, was suddenly masked. Twenty minutes later Burgoyne cautiously raised his head and looked seaward. A flickering white light informed him that the vessel was steaming rapidly away.

"Hang on here," he whispered to his companions "I'm going to have a look round."

He was back in a quarter of an hour, with the report that he had seen the pirate guard form up and march through the gate of the compound.

"That leaves us with a tolerably free hand," he added. "I was afraid they'd muster all hands and call the roll. No sign of Minalto yet, I suppose?"

"None," replied Withers, who had been holding on to the rope. "He's a bit behind time. I hope nothing's gone wrong."

"So do I," agreed Alwyn fervently.

Slowly the minutes passed. Momentarily doubts grew in the minds of the three watchers. Even Alwyn's faith in Minalto's powers was waning.

"I'll take on now," he remarked, relieving the Second Engineer at the rope.

He had barely resumed his "trick" when the manila rope was almost jerked out of his hand. From the unseen depths below came three decided tugs.

"He's back, lads," whispered Burgoyne joyously. "All together. Man the rope – walk back."

It was no easy task to hoist the ponderous seaman, but at length Jasper Minalto's head and shoulders appeared above the edge of the cliff. With no apparent effort he swung himself up by the projecting beam and gained the summit. Slipping out of the bowline, he shook himself like a Newfoundland dog, for water was dripping from his saturated clothes.

"I've been there sartain sure," he announced coolly, "an' back agen, sir. If you'm your doubts, sir, there's my 'nitials scratched on ter boat's back-board, fair an' legible-like s'long as you looks carefully."

Burgoyne brought his hand down upon the seaman's shoulder.

"Splendid!" he exclaimed. "You must spin your yarn later, after we've packed up and stowed away the gear. There's not much time. But, in any case, Minalto, you've won your place in the boat."

"Thank'ee, sir," replied Jasper gratefully.

Grey dawn was showing over the eastern height of the island when the four men returned to their huts. Burgoyne reported "all well" to Captain Blair, who, declining to hear details, told the Third Officer to turn in.

"You can't work watch and watch for two successive days unless you have a 'caulk'," he added. "It will be another hour and a quarter before the hands are turned out. Make the best of it."

But the Old Man was wrong in his estimate. No attempt was made to summon the crews of the three captured ships to their forced labour. They were piped to breakfast and then allowed to "stand easy", while armed pirates patrolled the inner circle of huts in addition to augmenting the guards in the two block-houses.

"Something's in the wind," declared Captain Blair. "The vessel that used her searchlight last night is evidently beating up for the island."

Soon there was no doubt on the point. From the compound the heights commanding the harbour and eastern approach to the island were plainly visible. Bodies of pirates were being rushed up to the concealed gun emplacements, which they could reach without being seen from seaward. Others were hurrying towards the tunnel, with the idea of manning the machine-guns that swept the entrance to the harbour and the only landing-place.

"The ball's about to commence," said Branscombe. "Wonder who'll open fire first?"

The prisoners listened in breathless suspense for the crash of the opening contest between the warship – or whatever she might be – and the quick-firers comprising the principal defences of the island. At intervals a powerful syren boomed out its raucous wail, demanding in Morse Code whether there were any people on the island.

Presently the sound came from the south'ard and then the west'ard, but no reply was sent from the pirates lying low on the apparently uninhabited island.

An hour later the captives caught sight of the trucks and aerials of a two-masted vessel proceeding on an easterly course at a distance of about two miles north of the island. Then the two mastheads vanished behind the rising ground; but from the fact that the batteries were still manned the Donibristle's people drew what proved to be a correct conclusion that the vessel had once more taken up a position off the eastern face of the secret base.

At noon, the prisoners still standing easy, Captain Blair called a meeting of officers to receive the reports of the investigating party.

It was Jasper Minalto's recital which created the greatest interest. After parting with Mr. Burgoyne on the shore, he said he swam to the reef, landing without difficulty on a flat expanse of coral. Although the reef averaged twenty yards in width and the state of the tide was almost low-water, the breakers swept far across the coral barrier before they expended their strength. Had it been anything near approaching high-water progress along the reef would have been extremely dangerous, if not impracticable.

But in present circumstances Minalto found the reef "fair going". There were several deep and narrow gulleys to be crossed, while there was a strong tidal current setting out of the only possible boat channel – not taking into consideration the ship passage – which was on the extreme south-western part of the reef.

It required a strenuous effort to swim across the narrow gap, but Minalto expressed an opinion that at dead low-water, or thereabouts, there would be little or no current.

Off the south-eastern end of the island he found himself quite a mile from shore, but on the eastern side the reef converged towards the island. Nevertheless he had to swim a quarter of a mile, aided by the set of the current, to gain the long, narrow and lofty ledge of rock that screened the harbour in which the Malfilio and her prizes were lying.

Here the buoys laid down the previous day by the Donibristle's crew helped him considerably, since he was able to hang on to them and rest as he made his way up the narrow channel.

Swimming close to the rocks on the island side of the channel, he arrived at the entrance to the harbour, and was glad to find his feet touch bottom just within the southern spur of rock that practically enclosed the anchorage.

From that point he waded until he reached the sandy beach. Everything was quiet. Keeping close to the cliff he passed the boatsheds and almost tripped over the chain securing the hauled-up boats.

Arriving at his goal, Minalto, as he told Burgoyne, scratched his initials upon the lifeboat's back-board. Then, having established his claim, he began to retrace his course.

At that moment he was considerably taken aback by seeing a light flash across the sky. His first thought was that the pirates had discovered him, but upon second consideration he rightly concluded that the flash came from a searchlight in the offing.

Before he had gone very far a faint light blinked from a point half-way up the cliff and immediately above (so he judged) the entrance to the tunnel. It was promptly answered by a light from the Malfilio and in a few minutes the crew of the pirate cruiser were standing to their guns. From where Minalto stood he could see all the starboard guns trained upon the entrance to the harbour, and rather apprehensively he wondered what would happen to him if they opened fire when he was swimming through that narrow gap.

He remained for some minutes crouching against the cliff, until it occurred to him that time and tide wait for no man, and that if he were to return by the way he came he would have to hurry his movements.

Minalto took the water as noiselessly as an otter. Swimming dog-stroke in order to minimize the phosphorescent swirl of his wake, he kept close to the cliffs – so close, in fact, that once his right knee came into sharp contact with a rock.

Then came the crucial point of his return journey – the passage of the harbour mouth. Dozens of pairs of eyes must, he knew, be peering in that direction, but he reckoned on the possibility that while they were looking for a large object, namely an armed boat from the warship off the island, they would fail to detect a small one – the head of the swimmer.

Unobserved he cleared the projecting headland, and working from buoy to buoy along the south approach channel until he came in view of the reef, gained a "kicking-off" position for the longest and most strenuous of his many swims that night.

Although the sea was warm he was beginning to feel that "water-logged" sensation that results from keeping in too long. Alternately swimming on his breast and back he continued doggedly, knowing that if he rested he would be swept out of his course by the steady indraught into the lagoon, for by this time the young flood was making.

At length he gained the reef, rubbed his cramped limbs, and set off briskly to the point nearest that part of the island whence he had set out, and an hour and a half later he was being hauled up the cliff.

Jasper Minalto had told his story, without any embellishments, in the broad, burring dialect of the West Country. But behind that simple narrative his listeners detected a ring of indomitability that had brought the man safely through the grave perils by land and sea.

"That coral is most heavy on shoe leather," he remarked. "Fair cut to pieces 'un is. But nex' time 'twill be only one way, like; seein' as how us be a-comin' back wi' the boat."

"You think we'll be able to launch the lifeboat and get her round without being spotted?" asked Captain Blair.

"We'd best wait till the Malfilio's a-put to sea, sir," replied Minalto. "There wur nobody on the beach as far as I could see, an' t' other craft wur quiet enow."

"It was the vessel in the offing that put the crew of the Malfilio on the qui vive, I fancy," observed Burgoyne. "We'll have to take the ship into consideration, I'm afraid, sir. That is, if we are to take advantage of these moonless nights."

"We'll have to," decided the Old Man. "We've five clear days before the new moon grows sufficiently to cause trouble. Failing that it will mean a fortnight's delay – and then it may be too late. And then there's the question of fresh water," he added, still smarting from the effect of his splendid failure. "That is the question."

"What's wrang wi' a bit o' canvas?" inquired Angus. "A pair o' canvas tanks fitted 'tween thwarts'll just dae fine."

"A good idea, Mr. Angus," said the skipper. "We'll have to knock up a couple of canvas tanks. There's the question of evaporation and leakage by the boat heeling to be taken into account."

"And, perhaps, the water might be tainted by the canvas," added Alwyn.

"Havers, mon!" ejaculated the First Engineer scornfully. "May ye never hae wurrse. Mony a day I've drunk bad water – an' bad whusky forbye, an' I'll live to dae it again," he added with an air of finality. "We'll get on with it," decided Captain Blair. "After all, beggars can't be choosers. Any more points to raise? None. Very well, then; unless anything unforeseen takes place Mr. Burgoyne and Minalto will bring the boat round to the west beach at – ?"

"Three a.m. on Thursday," said Alwyn.

For the remainder of the day the captives' "stand easy" continued. As far as the men taking part in the previous night's work were concerned nothing could have been more welcome. It enabled them to make up arrears from loss of sleep and strenuous activity. Nevertheless the additional length of line for the guide-rope was forthcoming, the canvas water-tanks were sewn up and tested, and more provisions lowered and hidden in the cave.

There remained three clear days before the die was cast and the momentous step taken – unless events over which the late officers and crew of the Donibristle had no control should necessitate a hurried change of plans.

Just before sunset the guns' crews were withdrawn from the emplacements, and the guards stationed outside the huts were marched out of the compound, so apparently Señor Ramon Porfirio was satisfied that the vessel that had caused him great uneasiness had really taken her departure.

CHAPTER XVI

Captain Consett's Report

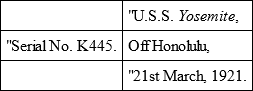

Extract from the Report of Captain Cyrus P. Consett, commanding U.S.S. Yosemite.

"To Rear-Admiral Josiah N. Felix,

"Commanding Third Pacific Squadron, U.S.N.

"Sir,

"I have the honour to report that in execution of previous orders I have carefully examined the area bounded by the 20th and 40th parallels and between 180° longitude and 160° W. longitude, paying particular attention to the uninhabited islands comprising the Ocean Group.