полная версия

полная версияThe Ancient City

But Mokes had never danced the Virginia reel – had seen it once at a servants’ ball, he believed.

“What are you doing, Sara?” I said, sleepily, from the majestic old bed, with its high carved posts and net curtains. “It is after eleven; do put up that pencil, at least for to-night.”

“I am amusing myself writing up the sail this afternoon. Do you want to hear it?”

“If it isn’t historical.”

“Historical! As though I could amuse myself historically!”

“It mustn’t be tragedy either: harrowing up the emotions so late at night is as bad as mince-pie.”

“It is light comedy, I think – possibly farce. Now listen: it begins with an ‘Oh’ on a high note, sliding down this way: ‘Oh-o-o-o-o-h!’

“MATANZAS RIVER“Oh! rocking on the little blue waves,While, flocking over Huguenot graves,Come the sickle-bill curlews, the wild laughing loons,The heavy old pelicans flying in platoonsLow down on the water with their feet out behind,Looking for a sand-bar which is just to their mind,Eying us scornfully, for very great fools,In which view the porpoises, coming up in schools,Agree, and wonder whyWe neither swim nor fly.“Oh! sailing on away to the south,There, hailing us at the river’s mouth,Stands the old Spanish look-out, where ages agoA watch was kept, day and night, for the evil foe —Simple-minded Huguenots fleeing here from France,All carefully massacred by the Spaniard’s lanceFor the glory of God; we look o’er the side,As if to see their white bones lying ’neath the tideOf the river whose nameIs reddened with the shame.“Oh! beating past Anastasia Isle,Where, greeting us, the light-houses smile,The old coquina beacon, with its wave-washed walls,Where the spray of the breakers ’gainst the low door falls,The new mighty watch-tower all striped in black and white,That looks out to sea every minute of the night,And by day, for a change, doth lazily standWith its eye on the green of the Florida land,And every thing doth spy —E’en us, as we sail by.“Oh! scudding up before wind and tide,Where, studding all the coast alongside,Miles of oysters bristling stand, their edges like knives,Million million fiddler-crabs, walking with their wives,At the shadow of our sail climb helter-skelter downIn their holes, which are houses of the fiddler-crab town;While the bald-headed eagle, coming in from the sea,Swoops down upon the fish-hawk, fishing patiently,And carries off his spoil,With kingly scorn of toil.“Oh! floating on the sea-river’s brine,Where, noting each ripple of the line,The old Minorcan fishermen, swarthy and slow,Sit watching for the drum-fish, drumming down below;Now and then along shore their dusky dug-outs pass,Coming home laden down with clams and marsh grass;One paddles, one rows, in their outlandish way,But they pause to salute us, and give us good-dayIn soft Minorcan speech,As they pass, near the beach.“Oh! sweeping home, where dark, in the north,See, keeping watch, San Marco looms forth,With its gray ruined towers in the red sunset glow,Mounting guard o’er the tide as it ebbs to and fro;We hear the evening gun as we reach the sea-wall,But soft on our ears the water-murmurs fall,Voices of the river, calling ‘Stay! stay! stay!Children of the Northland, why flee so soon away?’Though we go, dear river,Thou art ours forever.”After I had fallen asleep, haunted by the marching time of Sara’s verse, I dreamed that there was a hand tapping at my chamber door, and, half roused, I said to myself that it was only dreams, and nothing more. But it kept on, and finally, wide awake, I recognized the touch of mortal fingers, and withdrew the bolt. Aunt Diana rushed in, pale and disheveled in the moonlight.

“What is the matter?” I exclaimed.

“Niece Martha,” replied Aunt Di, sinking into a chair, “Iris has disappeared!”

Grand tableau, in which Sara took part from the majestic bed.

“She went to her room an hour ago,” pursued Aunt Di; “it is next to mine, you know, and I went in there just now for some camphor, and found her gone!”

“Dear, dear! Where can the child have gone to?”

“An elopement,” said Aunt Di, in a sepulchral tone.

“Not Mokes?”

“No. If it had been Mokes, I should not have – that is to say, it would have been highly reprehensible in Iris, but – However, it is not Mokes; he is sound asleep in his room; I sent there to see.” And Aunt Diana betook herself to her handkerchief.

“Can it be John Hoffman?” I mused, half to myself.

“Mr. Hoffman went up to his room some time ago,” said Sara.

“And pray how do you know, Miss St. John?” asked Aunt Di, coming out stiffly from behind her handkerchief. “Mr. Hoffman would have been very glad to – and, as it happens, he is not in his room at all.”

“Then of course – Oh, irretrievable folly!” I exclaimed, in dismay.

“But it isn’t John Hoffman, I tell you,” said Aunt Diana, relapsing into dejection again. “He has gone out sailing with the Van Andens; I heard them asking him – a moonlight excursion.”

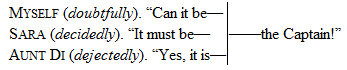

Then the three of us united:

IN TWO PARTS. – PART II

“The tide comes in; the birds fly low,As if to catch our speech:Ah, Destiny! why must we ever goAway from the Florida Beach?”AUNT DIANA declared that I must go with her back to the hotel, and I in my turn declared that if I went Sara must accompany me; so it ended in our taking the key of the house from the sleepy Sabre-boy and all three going back together through the moon-lighted street across the plaza to the hotel. Although it was approaching midnight, the Ancient City had yet no thought of sleep. Its idle inhabitants believed in taking the best of life, and so on moonlight nights they roamed about, two and two, or leaned over their balconies chatting with friends across the way in an easy-going, irregular fashion, which would have distracted an orthodox New England village, where the lights are out at ten o’clock, or they know the reason why. When near the hotel we saw John Hoffman coming from the Basin.

“We had better tell him,” I suggested.

“Oh no,” said Aunt Di, holding me back.

“But we must have somebody with us if we are going any farther to-night, aunt, and he is the best person. – Mr. Hoffman, did you enjoy the sail?”

“I did not go,” answered John, looking somewhat surprised to see us confronting him at that hour, like the three witches of Macbeth. Aunt Di was disheveled, and so was I, while Sara’s golden hair was tumbling about her shoulders under the hat she had hastily tied on.

“Have you been out all the evening?” asked Aunt Di, suspiciously.

“I went to my room an hour ago, but the night was so beautiful I slipped down the back stairs, so as to not disturb the household, and came out again to walk on the sea-wall.”

“Sara did hear him go up to his room: she knows his step, then,” I thought. But I could not stop to ponder over this discovery. “Mr. Hoffman,” I said, “you find us in some perplexity. Miss Carew is out loitering somewhere, in the moonlight, and, like the heedless child she is, has forgotten the hour. We are looking for her, but have no idea where she has gone.”

“Probably the demi-lune,” suggested John. Then, catching the ominous expression of Aunt Diana’s face, he added, “They have all gone out to the Rose Garden by moonlight, I think.”

“All?”

“Miss Sharp and the Professor.”

All three of us. “Miss Sharp and the Professor?”

John (carelessly). “The Captain too, of course.”

All three of us. “The Captain too, of course!”

John. “Suppose we stroll out that way and join them?”

Myself. “The very thing – it is such a lovely evening!” Then to Aunt Di, under my breath, “You see, it is only one of Iris’s wild escapades, aunt; we must make light of it as a child’s freak. We had better stroll out that way, and all walk back together, as though it was a matter of course.”

Aunt Di. “Miss Sharp and the Professor!”

Sara. “What a madcap freak!”

Aunt Di. “Not at all, not at all, Miss St. John. I am at a loss to know what you mean by madcap. My niece is simply taking a moonlight walk in company with her governess and Professor Macquoid, one of the most distinguished scientific men in the country, as I presume you are aware.”

Brave Aunt Di! The first stupor over, how she rallied like a Trojan to the fight!

We went out narrow little Charlotte Street – the business avenue of the town.

“A few years ago there was not a sign in St. Augustine,” said John. “People kept a few things for sale in a room on the ground-floor of their dwellings, and you must find them out as best you could. They seemed to consider it a favor that they allowed you to come in and buy. They tolerated you, nothing more.”

“It is beyond any thing, their ideas of business,” said Aunt Diana. “The other day we went into one of the shops to look at some palmetto hats. The mistress sat in a rocking-chair slowly fanning herself. ‘We wish to look at some hats,’ I said. ‘There they are,’ she replied, pointing toward the table. She did not rise, but continued rocking and fanning with an air that said, ‘Yes, I sell hats, but under protest, mind you.’ After an unaided search I found a hat which might have suited me with a slight alteration – five minutes’ work, perhaps. I mentioned what changes I desired, but the mistress interrupted me with, ‘We never alter trimmings.’ ‘But this will not take five minutes,’ I began; ‘just take your scissors and – ’ ‘Oh, I never do the work myself,’ replied Majestic, breaking in again with a languid smile; ‘and really I do not know of any one who could do it at present. Now you Northern ladies are different, I suppose.’ ‘I should think we were,’ I said, laying down the hat and walking out of the little six-by-nine parlor.”

“I wonder if the people still cherish any dislike, against the Northerners?” I said, when Aunt Di had finished her story with a general complaint against the manners of her own sex when they undertake to keep shop, North or South.

“Some of the Minorcans do, I think,” said John; “and many of the people regret the incursion of rich winter residents, who buy up the land for their grand mansions, raise the prices of every thing, and eventually will crowd all the poorer houses beyond the gates. But there are very few of the old leading families left here now. The ancien régime has passed away, the new order of things is distasteful to them, and they have gone, never to return.”

Turning into St. George Street, we found at the northern end of the town the old City Gates, the most picturesque ruin of picturesque St. Augustine. The two pillars are moresque, surmounted by a carved pomegranate, and attached are portions of the wall, which, together with an outer ditch, once extended from the Castle of San Marco, a short distance to the east, across the peninsula to the San Sebastian, on the west, thus fortifying the town against all approaches by land. The position of St. Augustine is almost insular. Tide-water sweeps up around and behind it, and to this and the ever-present sea-breeze must be attributed the wonderful health of the town, which not only exists, but is pre-eminent, in spite of a neglect of sanitary regulations which would not be endured one day in the villages of the North.

Passing through the old gateway, we came out upon the Shell Road, the grand boulevard of the future, as yet but a few yards in length.

“They make about ten feet a year,” said John; “and when they are at work, all I can say unto you is, ‘Beware!’ You suppose it is a load of empty shells they are throwing down; but no. Have they time, forsooth, to take out the oysters, these hard-pressed workmen of St. Augustine? By no means; and so down they go, oysters and all, and the road makes known its extension on the evening breezes.”

The soft moonlight lay on the green waste beyond the gates, lighting up the North River and its silver sand-hills. The old fort loomed up dark and frowning, but the moonlight shone through its ruined turrets, and only the birds of the night kept watch on its desolate battlements. The city lay behind us. It had never dared to stretch much beyond the old gates, and the few people who did live outside were spoken of as very far off – a sort of Bedouins of the desert encamping temporarily on the green. As we went on the moonlight lighted up the white head-stones of a little cemetery on the left side of the road.

“This is one of the disappointing cemeteries that was ‘nothing to speak of,’ I suppose,” said Sara.

“It is the Protestant cemetery,” replied John, “remarkable only for its ugliness and the number of inscriptions telling the same sad story of strangers in a strange land – persons brought here in quest of health from all parts of the country, only to die far away from home.”

“Where is the old Huguenot burying-ground?” asked Aunt Di.

“The Huguenots, poor fellows, never had a burying-ground, nor so much even as a burying, as far as I can learn,” said Sara.

“But there is one somewhere,” pursued Aunt Di. “I have heard it described as a spot of much interest.”

“That has been a standing item for years in all the Florida guide-books,” said John, “systematically repeated in the latest editions. They will give up a good deal, but that cherished Huguenot cemetery they must and will retain. The Huguenots, poor fellows, as Miss St. John says, never had a cemetery here, and it is only within comparatively modern times that there has been any Protestant cemetery whatever. Formerly the bodies of all persons not Romanists were sent across to the island for sepulture.”

The Shell Road having come to an end, we walked on in the moonlight, now on little grass patches, now in the deep sand, passing a ruined stone wall, all that was left of a pleasant home, destroyed, like many other outlying residences, during the war. The myrtle thickets along the road-side were covered with the clambering curling sprays of the yellow jasmine, the lovely wild flower that brings the spring to Florida. We stopped to gather the wreaths of golden blossoms, and decked ourselves with them, Southern fashion. Every one wears the jasmine. When it first appears every one says, “Have you seen it? It has come!” And out they go to gather it, and bring it home in triumph.

Passing through the odd little wicket, which, with the old-fashioned turnstile, is used in Florida instead of a latched gate, we found ourselves in a green lane bordered at the far end with cedars. Here, down on the North River, was the Rose Garden, now standing with its silent house fast asleep in the moonlight.

“I do not see Iris,” said Aunt Diana, anxiously.

“There is somebody over on the other side of the hedge,” said Sara.

We looked, and beheld two figures bending down and apparently scratching in the earth with sticks.

“What in the world are they doing?” said Aunt Diana. “They can not be sowing seed in the middle of the night, can they?”

“They look like two ghouls,” said Sara, “and one of them has – yes, I am sure one of them has a bone.”

“It is Miss Sharp and the Professor,” said John.

It was. We streamed over in a body and confronted them. “So interesting!” began Miss Sharp, in explanatory haste. “At various times the fragments of no less than eight skeletons have been discovered here, it seems, and we have been so fortunate as to secure a relic, a valuable Huguenot relic;” and with pride she displayed her bone.

“Of course,” said Sara, “a massacre! What did I tell you, Martha, about their arising from the past and glaring at me?”

“Miss Sharp,” began Aunt Diana, grimly, “where is Iris?”

“Oh, she is right here, the dear child. Iris! Iris!”

But no Iris appeared.

“I assure you she has not left my side until – until now,” said the negligent shepherdess, peering about the shadowy garden. “Iris! Iris!”

“And pray, Miss Sharp, how long may be your ‘now?’ ” demanded Aunt Diana, with cutting emphasis.

This feminine colloquy had taken place at one side. The Professor dug on meanwhile with eager enthusiasm, only stopping to hand John another relic which he had just unearthed.

“Thank you,” said John, gravely; “but I could not think of depriving you.”

“Oh, I only meant you to hold it a while for me,” replied the Professor.

On the front steps leading to the piazza of the sleeping house we found the two delinquents. They rose as we came solemnly up the path.

“Why, Aunt Di, is that you? Who would have thought of your coming out here at this time of night?” began Iris, in her most innocent voice. The Captain stood twirling his blonde mustache with the air of a disinterested outsider.

“Don’t make a fuss, Aunt Di,” I whispered, warningly, under my breath. “It can’t be helped now. Take it easy; it’s the only way.”

Poor Aunt Di – take it easy! She gave a sort of gulp, and then came up equal to the occasion. “You may well be surprised, my dear,” she said, in a brisk tone, “but I have long wished to see the Rose Garden, and by moonlight the effect, of course, is much finer; quite – quite sylph-like, I should say,” she continued, looking around at the shadowy bushes. “We were out for a little stroll, Niece Martha, Miss St. John, and myself, and meeting Mr. Hoffman, he mentioned that you were out here, and so we thought we would stroll out and join you. Charming night, Captain?”

The Captain thought it was; and all the dangerous places having been thus nicely coated over, we started homeward. The roses grew in ranks between two high hedges, and blossomed all the year round. They were all asleep now on their stems, the full-bosomed, creamy beauties, the delicate white sylphs, and the gorgeous crimson sirens; but John woke up a superb souvenir-de-Malmaison, and fastened it in Iris’s dark hair: her hat, as usual, hung on her arm. Aunt Diana felt herself a little comforted; evidently the undoubted Knickerbocker antecedents were not frightened off by this midnight escapade, and Iris certainly looked enchantingly lovely in the moonlight, with her white dress and the rose in her hair. If Mokes were only here, and reconciled too. Happy thought! why should Mokes know? Aunt Diana was a skillful general: Mokes never knew.

“How large and still the house looks!” I said, as we turned toward the wicket; “who lives there?”

“Only the Rose Gardener,” answered John; “an old bachelor who loves his flowers and hates womankind. He lives all alone in his great airy house, cooks his solitary meals, tends his roses, and no doubt enjoys himself extremely.”

“Oh yes, extremely,” said Sara, in a sarcastic tone.

“You speak whereof you do know, I suppose, Miss St. John!”

“Precisely; I have tried the life, Mr. Hoffman.”

The Professor joined us at the gate, radiant and communicative. “All this soil, you will observe, is mingled with oyster shells to the depth of several feet,” he began. “This was done by the Spaniards for the purpose of enriching the ground. Ah! Miss Iris, I did not at first perceive you in the shadow. You have a rose, I see. Although – ahem – not given to the quotation of poetry, nevertheless there is one verse which, with your permission, I will now repeat as applicable to the present occasion:

“ ‘Fair Phillis walks the dewy green;A happy rose lies in her hair;But, ah! the roses in her cheeksAre yet more fair!’ ”“Pray, Miss Sharp, can you not dispense with that horrible bone?” said Aunt Diana, in an under-tone. “Really, it makes me quite nervous to see it dangling.”

“Oh, certainly,” replied the governess, affably, dropping the relic into her pocket. “I myself, however, am never nervous where science is concerned.”

“Over there on the left,” began the Professor again, “is the site of a little mission church built as long ago as 1592 on the banks of a tide-water creek. A young Indian chieftain, a convert, conceiving himself aggrieved by the rules of the new religion, incited his followers to attack the missionary. They rushed in upon him, and informed him of his fate. He reasoned with them, but in vain; and at last, as a final request, he obtained permission to celebrate mass before he died. The Indians sat down on the floor of the little chapel, the father put on his robes and began. No doubt he hoped to soften their hearts by the holy service, but in vain; the last word spoken, they fell upon him and – ”

“Massacred him,” concluded Sara. “You need not go on, Sir. I know all about it. I was there.”

“You were there, Miss St. John!”

“Certainly,” replied Sara, calmly. “I am now convinced that in some anterior state of existence I have assisted, as the French say, at all the Florida massacres. Indian, Spanish, or Huguenot, it makes no difference to me. I was there!”

“I trust our young friend is not tinged with Swedenborgianism,” said the Professor aside to John Hoffman. “The errors of those doctrines have been fully exposed. I trust she is orthodox.”

“Really, I do not know what she is,” replied John.

“Oh yes, you do,” said Sara, overhearing. “She is heterodox, you know; decidedly heterodox.”

In the mean while Aunt Diana kept firmly by the side of the Captain. It is safe to say that the young man was never before called upon to answer so many questions in a given space of time. The entire history of the late war, the organization of the army, the military condition of Europe, and, indeed, of the whole world, were only a portion of the subjects with which Aunt Di tackled him on the way home. Iris stood it a while, and then, with the happy facility of youth, she slipped aside, and joined John Hoffman. Iris was a charming little creature, but, so far, for “staying” qualities she was not remarkable.

A second time we passed the cemetery. “I have not as yet investigated the subject,” said the Professor, “but I suppose this to be the Huguenot burying-ground.”

“Oh yes,” exclaimed Miss Sharp; “mentioned in my guide-book as a spot of much interest. How thrilling to think that those early Huguenots, those historical victims of Menendez, lie here– here in this quiet spot, so near, you know, and yet – and yet so far!” she concluded, vaguely conscious that she had heard that before somewhere, although she could not place it. She had forgotten that eye which, mixed in some poetic way with a star, has figured so often in the musical performances of the female seminaries of our land.

“Very thrilling; especially when we remember that they must have gathered up their own bones, swum up all the way from Matanzas, and buried each other one by one,” said Sara.

“And even that don’t account for the last man,” added John.

Miss Sharp drew off her forces, and retired in good order.

“Iris,” I said, the next morning, “come here and give an account of yourself. What do you mean, you gypsy, by such performances as that of last night?”

“I only meant a moonlight walk, Cousin Martha. I knew I never could persuade Aunt Di, so I took Miss Sharp.”

“I am surprised that she consented.”

“At first she did refuse; but when I told her that the Professor was going, she said that under those circumstances, as we might expect much valuable information on the way, she would give her consent.”

“And the Professor?”

“Oh, I asked him, of course; he is the most good-natured old gentleman in the world; I can always make him do any thing I please. But poor Miss Sharp – how Aunt Di has been talking to her this morning! ‘How you, at your age,’ was part of it.”

A week later we were taken to see the old Buckingham Smith place, now the property of a Northern gentleman, who has built a modern winter residence on the site of the old house.

“This is her creek, Aunt Di,” I said, as the avenue leading to the house crossed a small muddy ditch.

“Whose, Niece Martha?”

“Maria Sanchez, of course. Don’t you remember the mysterious watery heroine who navigated these marshes several centuries ago? She perfectly haunts me! Talk about Huguenots arising and glaring at you, Sara; they are nothing to this Maria. The question is, Who was she?”

“I know,” answered Iris. “She is my old friend of the Dismal Swamp. ‘They made her a grave too cold and damp,’ you know, and she refused to stay in it. ‘Her fire-fly lamp I soon shall see, her paddle I soon shall hear – ’ ”

“Well, if you do, let me know,” I said. “She must be a very muddy sort of a ghost; there isn’t more than a spoonful of water in her creek as far down as I can see.”

“But no doubt it was a deep tide-water stream in its day, Miss Martha,” said John Hoffman; “deep enough for either romance or drowning.”