Полная версия

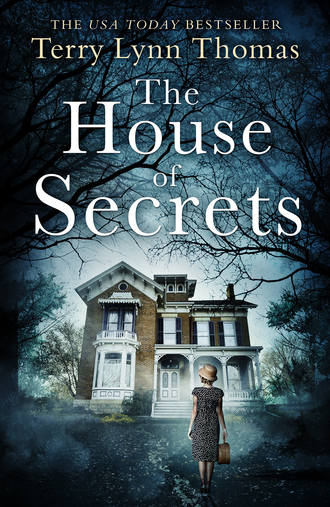

The House of Secrets

The knowledge that this strange man spoke the truth welled up from some hidden place deep within.

‘Picture two worlds: that of the living and another world across the veil, where souls go,’ he continued. ‘They aren’t up in the sky or down below. They’re around us all the time. Some souls hover between the two worlds. They need help crossing over.’

‘How do you know all this?’

‘I’ve had a lot of death in my life. My mother died giving birth to my sister, my father died of pneumonia, my sister died in 1919 of the influenza. I have much to be grateful for, but there was a melancholia about me, a sadness which, I believe, came from all that death. I came to a realization not too long ago that this sadness resulted from the loss of my family and caused me to rethink my priorities. The occult has always intrigued me. Injustice infuriates me. I believe that you are a medium who has been treated unfairly by a society that doesn’t even know people with your abilities exist. I want to help people like you.’

‘How?’

‘I would like to hypnotize you. I can teach you to control what you see by making suggestions to your subconscious mind while you are in a deeply relaxed state.’

‘Hypnotize me? I don’t know if that’s a good idea. Would I be awake?’

‘You would be wide awake, just relaxed. You will remember everything. There’s no secret or hidden agenda.’

I shook my head.

‘You don’t have to decide now. I don’t want to do anything until you trust me and want to participate. Meanwhile, I do have a job for you. If you get to know me better, start to feel comfortable, and you want my help, we can discuss this further. I do need a typist, so let me tell you about that. Let me tell you about the job, what I expect of you, and we can go from there. Does that sound fair?’

‘Can you tell me about Zeke?’

‘Of course.’ At Dr Geisler’s earnest tone, I relaxed and melted back into the sofa. ‘My wife doesn’t know about Zeke’s work. As far as she’s concerned, he’s here to recuperate and rest. You know his work – well, he can’t be in the public eye. It’s not safe for him to be in a regular hospital, as you can imagine.’

‘He’s not suffering from any psychiatric injuries?’ My voice came out like a croak. ‘He suffered from nightmares before.’

‘He has no psychiatric injuries. He needs rest and physical rehabilitation. My wife is a skilled rehabilitative nurse. She will do all she can to help Zeke.’

‘How come he never—’ I couldn’t say it out loud, couldn’t acknowledge with words that Zeke never contacted me directly.

‘I’m sorry. That is a question best directed to Zeke.’

Dr Geisler crossed the room to where a pitcher and several glasses rested on a bureau. He poured a glass of water and brought it to me. I took a few sips, not realizing how thirsty I’d become until the cold water hit the back of my throat.

‘Will you stay? I’ll pay you one hundred and fifty dollars a month, plus room and board. We’ve a nice room for you. You’ll be close to Zeke, and Mrs McDougal’s a good cook. I think you might be happy here.’

‘Yes, I will stay.’ What other choice do I have?

‘I’ll have Mrs McDougal show you to your room. She will fix you some breakfast, and we can get started right away.’

We shook hands to seal our arrangement. As if on cue, Mrs McDougal appeared.

I had found a place to hide.

* * *

I followed Mrs McDougal into the foyer. The desk by the front door stood empty now. She led me up the far staircase, wide enough for four people to walk abreast. A large window at the landing and the sconces that were situated along the walls provided the only light in the second-floor corridor. With a flick of the switch, Mrs McDougal turned the lights on. The walls up here were the same honey-coloured wood as downstairs. I counted the closed doors as we passed them, so I wouldn’t end up in someone else’s room when I navigated the corridors by myself.

‘Has this house always been a hospital?’ I asked Mrs McDougal.

‘Oh, no. It used to be Dr Geisler’s family residence. When Dr Geisler and Bethany married, they decided to turn it into a hospital. Bethany is very passionate about helping people. She’s a nurse, you know. Dr Geisler wants to cure their minds. They are both very noble people.’

When we came to a stop at the sixth door, Mrs McDougal pulled a skeleton key out of her pocket, slid it into the lock, and pushed the door open. The boarding house where I had been staying had two or three beds crammed into tiny rooms no bigger than closets, and one bathroom, with no hope of hot water, shared by a gaggle of complaining women. This room was large enough to dance in, with floral wallpaper in pale shades of yellow. I walked across wool carpet the colour of sweet cream to the window that took up the entire wall, and pushed aside the heavy curtains.

Below me, San Francisco pulsed with its own life. A milk truck drove by, a woman pushed a baby carriage, the mailman passed her, nodding as he lifted his cap. I walked through another tall door into a bathroom with a claw-foot tub deep enough to float in. I wondered if there would be enough hot water to fill it.

‘The hot water heater is turned on at three o’clock every afternoon, so you can bathe after that time. We’ve plenty of hot water once the heater is turned on, so go ahead and fill your tub. You’ll have hot water until we wash up after dinner. If you require hot water before that, you’ll have to ask one of the girls to bring it up to you from the kitchen. I keep a kettle on the stove at all times.’

‘I’m sure I’ll be fine with the cold water,’ I said.

‘I’ve seen to the unpacking of your things. Once you decide where you’d like to hang your paintings, I’ll make arrangements to have them hung for you.’ Mrs McDougal took a gold watch from her pocket. ‘It’s nine o’clock. Would you like some breakfast? You look like you could use a good meal. We eat well here, despite the rationing and the shortage of meat. My sister keeps chickens and has a nice victory garden on her roof. She lets me plant what I need for the house there too. Even though I can’t, for the life of me, get meat, we do have plenty of fresh vegetables.’

‘Breakfast would be lovely, if it’s not too much trouble.’

‘I’ll leave you to freshen up. Can you find your way downstairs? Just follow the corridor to the back stairs and that will take you to the kitchen.’ Mrs McDougal paused at the door. ‘I know it’s none of my business, Miss Bennett, but you were so brave, the way you testified at the trial. Jack Bennett got away with murder, just as sure as the day is long, but never mind that. You’re here now, and that is all that matters.’

Hot blood rushed to my ears.

‘Oh, I’ve gone and embarrassed you. Forgive me.’

‘I’ve had a hard time getting settled—’

‘You’ve no reason to worry. You’re in good hands. Dr Geisler is very easy to work for. You come down to the kitchen, and I’ll have some food ready for you.’

I splashed icy cold water on my face and reached for one of the plush ivory towels, surprised to find that my hands shook.

‘Take a drop or two, Sarah. They won’t hurt you, and they will help you cope.’ I could hear Dr Upton’s voice. Enough of those thoughts. I had been given a new beginning. Hard work and the satisfaction that comes from a job well done would see me through.

With fresh resolve, I went to unpack, only to find that, true to her word, Mrs McDougal had already seen to it. My suitcase had been taken away and my meagre belongings had been arranged in the armoire that rose all the way to the ceiling. The seascapes I had taken when I fled Bennett House were now on top of the highboy, propped against the wall. One depicted the blue-green sea and the summer sky, while the other captured the dark blues and greys of the winter sea.

The books that I carried with me, Rebecca, The Murder at the Vicarage, and The Uninvited – last year’s best seller by Dorothy Macardle – had been placed in the small bookcase nestled in the corner of the room. I ran my fingers over the familiar worn spines, glad to have a touchstone from my past during this new phase of my life. A small writing desk rested in front of the window. I opened the drawer to it, and saw the pile of letters from Cynthia Forrester, held together with a white ribbon, all unopened.

Cynthia Forrester, the reporter from the San Francisco Chronicle, had told my story after Jack Bennett’s trial with a cool, objective voice. I took a chance and trusted her. She now had a byline and a promising career as a feature writer, and the hours we spent together while she interviewed me had kindled a friendship between us. After the story was published, Cynthia had reached out as a friend, with phone calls and invitations to lunch and dinner, all of which I declined. She wrote several letters, which I never opened. One of these days, I promised myself, as I pushed the drawer shut.

Not ready to go downstairs yet, I moved over to the window and pressed my forehead against the cold glass. Below me, the traffic on Jackson Street moved along. I studied the houses across the street, noting the blue stars in the windows, the indication of how many sons and fathers were overseas fighting. Every day, mothers, sisters, and wives scoured the newspaper, hoping their loved ones would not make the list of fatalities. Every day, some of those same mothers, sisters, and wives would receive a visit from the Western Union boy, bearing dreaded news, and the blue stars that hung in the windows would be changed to gold.

I shook off thoughts of the injured and dead soldiers and watched as a diaper truck stopped in front of the house across the street. A white-coated deliveryman jumped out of the driver’s side, opened the back of the truck, and hoisted a bundle of clean diapers onto his shoulder. Just as he reached the porch, a woman in a starched maid’s uniform opened the door. She took the bundle from the driver, set it aside, and rushed into his open arms. They fell into a deep kiss. The woman broke their connection. The man kept reaching for her, but she smiled and pushed him away. She handed him a bulky laundry bag, then stepped into the house and closed the door behind her.

As the deliveryman climbed back into his truck, a young woman dressed in a stylish coat and matching hat pushed a buggy up to the front of the house. The maid stepped out to meet the woman, smoothing down her apron before taking the baby from the woman’s arms.

I wondered what the mistress of the house would think of her maid’s stolen kiss with the diaper deliveryman.

‘Excuse me.’ A woman stood in my doorway. Her eyes darted about my room. ‘Did you see a tall, dark-haired man pass by?’

‘No. I’m sorry.’ She must be a patient, I realized.

She stepped into the room, surveying the opulent surroundings. ‘Your room is much nicer than mine. I’m an old friend of Matthew’s – Dr Geisler’s. I thought I saw … oh, never mind. My mind plays tricks on me. You must be the new secretary?’

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘Minna Summerly. Nice to meet you.’ She extended her hand and stepped close to me, moving with the lithesome grace of a ballet dancer.

‘Sarah Bennett.’

‘Oh, I know who you are. I knew that you’d take the job. In fact, I told Matthew – Dr Geisler – you would agree to work here.’

She noticed my bewildered expression.

‘Oh, I’m psychic. It’s a gift and a curse, if you want the truth. That’s why I’m here. Dr Geisler is trying to prove that mediums exist. I happen to be one. Truth be told, all of us here are big fans of yours. We followed the trial, you see. Everyone in the house has been cheering you on. I can’t imagine what it must have been like, testifying like that, being called mad by the toughest defence attorney in San Francisco. The newspapers were relentless, weren’t they? I swear those journalists would do anything for a story.’ She rattled on, impervious to my discomfort. ‘It’s going to be nice having someone young here. Dr Geisler and Bethany are good company, but they are a little focused on their work. Were you going downstairs?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Mrs McDougal has promised me breakfast.’

‘Allow me to show you the way.’ Minna tucked her arm in mine, and together we made our way along the corridor to the back staircase, which led to the kitchen. ‘I’m glad you are going to help Matthew. He’s a good man who cares deeply for those he treats. He needs someone to help him, so he can be free to pursue his other interest.’

‘Other interest?’

We came to a rest on a landing with two corridors leading off it. A man stood in the foyer, dressed in a cardigan with leather patches at the elbows. His glasses had slid down his nose, so he tilted his head back to look at us.

‘Mr Collins, do the nurses know you’re roaming around?’

‘You have light coming off you.’ Mr Collins spoke in a reverential whisper.

‘This is Sarah Bennett, Mr Collins. She is going to be working here.’

‘I know. She has light coming off her.’ Mr Collins turned and shuffled away, staring at his feet as he went.

‘He’s harmless,’ Minna said, as if she could read my thoughts. ‘Just pretend you’re speaking to a 2-year-old. Ask him to leave you alone, and he will. There’s no need to be afraid of him.’

‘I know. I’m just not used to …’

Not used to what? Having a job? A roof over my head? Having one single person say that they appreciate and understand the toll Jack Bennett’s murder trial has taken on me?

‘You’ll be fine here, Sarah. We’re all glad to have you. We’re going to be friends, I’m sure of it.’ When my stomach rumbled, Minna laughed. ‘If you go that way, you’ll find the kitchen. I’ll see you later.’

She walked down the corridor without a backward glance, leaving me to find my way to the kitchen.

* * *

I followed the enticing aroma of cinnamon and coffee and wound up in a large, modern kitchen. One entire wall consisted of tall windows, with French doors leading into a courtyard – a nice surprise for a house in the city. On a bright sunny morning these east-facing windows would fill the kitchen with morning light. A chopping block big enough for several people to work on stood in the centre of the room. A young girl, dressed in a grey cotton uniform with a white apron tied around her waist, kneaded dough under the watchful eyes of Mrs McDougal. When the girl saw me, she smiled.

‘Pay attention, Alice. Don’t work it too hard, my girl, or the dough won’t rise.’

‘Yes, Mrs McDougal,’ Alice said.

‘Miss Bennett, come in.’ Mrs McDougal beckoned me to sit at the refectory table in the corner, where a place had been laid for me. ‘I didn’t know if you like tea or coffee, so I made both.’

Indeed there were two pots by my place. I sat down and poured out coffee, just as Mrs McDougal took a plate out of the oven and put it down before me. Two eggs, browned toast, and a piece of bacon graced my plate. Real bacon. I could have wept.

‘However did you get bacon?’ I asked in awe, reluctant to touch it. California’s meat shortage had been in the headlines for weeks now, with no relief in sight, despite promises from the meat rationing board. Although sacrifices were necessary for the troops who fought overseas, I craved bacon and beef just as much as the next person.

‘It’s the last piece,’ Mrs McDougal said. ‘I just read that the food shortage is going to get worse. I can’t imagine it.’

‘They need farmers,’ Alice said. ‘My momma says that all the men who harvest the food have gone off to war.’

‘Pretty soon the women will be working in the fields,’ Mrs McDougal said.

‘Unless they join the WACS or the WAVES,’ Alice said. ‘My sister tried to volunteer, but they wouldn’t take her. She has bad vision.’

Mrs McDougal and Alice chatted while I ate. Every now and then Mrs McDougal would look at me, nodding in approval as I cleaned my plate. I hadn’t eaten this well since I left Bennett Cove. Dr Geisler came into the kitchen just as I finished my meal and reached for the pot to pour another a cup of coffee.

‘Ah, Sarah. Your timing is perfect,’ said Dr Geisler. He nodded at Alice. ‘Mrs McDougal, would you please bring another pot of coffee into the office for Sarah and me?’ He rubbed his hands together, eager as a schoolboy. ‘Come along. We’ve much to do.’

* * *

We walked through the foyer and up the staircase opposite that which led to my room. I gasped when we entered the room, not because of the view of the San Francisco Bay and Alcatraz, which was stunning. My fascination lay with the floor-to-ceiling bookcases that covered every wall, all of the shelves filled to the brim with books of all sorts.

‘May I?’ I gestured at the shelves.

‘Please.’ Dr Geisler nodded his approval.

Ivanhoe by Sir Walter Scott, The Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens, a well-worn edition of Balzac in its original French, James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans, The Life of Samuel Johnson by James Boswell, and a series of blue leather books that were too big to fit on the shelves were stacked on a library table.

Books. Books. Everywhere books. There were leather-bound tomes with golden letters on the spine, classics, some so old they should have been in a museum. There were medical textbooks, music books, art books, books about birds, and architecture, and cooking. A small section of one shelf held a stack of paperbacks by Mary Roberts Rinehart, Margery Allingham, and Lina Ethel White.

‘The mysteries belong to my wife. She has her own library upstairs, too.’ He came to stand next to me. ‘Books are my indulgence. I love to be surrounded by them.’

‘You have a remarkable collection,’ I said.

‘Consider my books at your disposal, Miss Bennett.’

I sat in the chair opposite him. Alice brought in a tray of coffee. Dr Geisler poured us each a cup.

‘I’ve arranged the handwritten notes for you to type into sections and put them in folders on your desk. You can work at your own pace, but I hope you can finish at least one of the folders, approximately five pages, each day. After you have typed up the pages, if you could handwrite a short summary of what you’ve typed, that will be helpful. Does that make sense?’

‘I think so,’ I said.

‘I think I’ll just let you get to it. If you have any questions or difficulties reading my handwriting, you can let me know. You need to be mindful of my spelling, as it is not my forte. There’s a Latin dictionary and a medical dictionary on that shelf.’ He pointed to two books on the credenza. ‘Does that arrangement suit?’

‘Of course.’

‘Follow me, please.’

Dr Geisler walked over to the corner of the office, where another door was nestled between two bookcases. He opened it and led me into the small room, with its own bookcase, but unlike the shelves in Dr Geisler’s office, these shelves were jammed full of files, stacks of paper, and scientific journals, all in a state of chaos. My desk sat under a large mullioned window. In the middle of it sat a new Underwood typewriter. The promised handwritten notes lay next to it, anchored in place with a bronze dragonfly. A fountain pen, a bottle of ink, and a brand-new steno pad lay next to the notes. Dr Geisler flicked on one of the lamps.

‘Is this all right? I thought you might want some privacy, and I’ve always liked this room.’ He eyed the chaotic shelves. ‘Once you’ve settled in, I’ll get someone to deal with this mess.’

‘Yes, thank you.’ I sat down at the desk.

‘Well, I’ll let you get to work then,’ he said.

‘Dr Geisler,’ I called out to him before he left the room. ‘Thank you.’

‘I believe we are going to help each other a great deal, Miss Bennett.’

‘Call me Sarah, please.’

‘Very well. And you may call me Matthew.’

He nodded and closed the door behind him.

And so I spent my first day at the Geisler Institute. The work proved interesting. Dr Geisler’s handwriting wasn’t schoolroom perfect, but I managed. The new typewriter was exquisite, especially in comparison to the rattle-trap machines at Miss Macky’s. Those relics had many keys that were stuck or missing and ribbons that were often as dry as a bone. A student had to type fifty words a minute before they were allowed access to the precious ink bottles that would bring the desiccated ribbons back to some semblance of life.

On this machine, the keys were smooth and well oiled, the ink crisp and black on the page. I started to work and fell into a routine. I would type three pages, proofread them, write a short summary, and move on. At two-thirty, when my stomach growled, I had finished eleven pages and felt very proud indeed. I pushed away from my desk, stood up, and started to stretch out my arms and neck, when Bethany came into the room.

‘I see you’ve settled in.’ She hovered around my desk. ‘Is everything to your liking? I wasn’t sure what sort of a chair you’d want. We’ve many to choose from, so if you aren’t comfortable, I hope you’ll speak up.’

‘Everything is fine,’ I said.

‘We’ll be going out for dinner this evening, so you can either have a tray in your room or eat in the kitchen with Mrs McDougal. Just let her know your preference.’

After a few minutes, I grabbed my purse and stepped into the now empty office. Remembering Dr Geisler’s offer to use his library, I perused the books on offer and had almost reached for Middlemarch, but settled instead on The Secret Adversary by Agatha Christie. I tucked the book under my arm, ready to head to my room for a few hours of reading time.

‘Hello, Sarah.’

I stopped dead in my tracks.

Zeke sat in one of the chairs that angled towards the window. A thin scar, shiny as a new penny and thin as the edge of a razor, ran from his cheekbone down to the edge of his full lips. I wondered who had sliced him so. His right arm was bandaged and held close to his body by a sling. A wooden cane leaned against his chair. A smattering of new grey hairs had come in around his temples, making him even more handsome.

‘I know. I look horrible. I didn’t mean to surprise you, but I get the distinct impression that you’re avoiding me.’

I sat down in the chair opposite him. ‘No, it’s not that.’

‘You don’t have to say anything. Just sit with me. We can figure out what to say to each other later.’ He reached over and took my hand in his. The heat of him came over me in waves, knocking me off guard.

‘I’ve missed you,’ he said.

‘I know.’ My words were but a whisper. I couldn’t find my voice. ‘I know that I got the job because of you. I’ll repay you somehow,’ I said.

A look of hurt flashed in his eyes. ‘You owe me nothing, Sarah.’

I nodded at him, mumbled some feeble excuse, and fled to the safety of my own room.

* * *

I spent the afternoon with the Agatha Christie mystery, trying without much success to push thoughts of Zeke to the back of my mind. When the clock struck five, I filled my claw-foot tub to the brim with piping hot water, and soaked until my skin wrinkled and the water turned tepid.

I spent a quiet evening with Mrs McDougal. We ate our meal together – potatoes au gratin, salad with green goddess dressing, and green beans – chatting like old friends, while various nurses and orderlies who worked the night shift came into the kitchen for tea or coffee.

Mrs McDougal didn’t ask prying questions, but every now and then I caught her staring with an inquisitive look. We both liked Inner Sanctum Mysteries, and after dinner we retired to the cosy sitting room where Mrs McDougal spent her free time. We listened to the show together on the new Philco radio with a mahogany cabinet, a gift from Dr Geisler.

Back in my bedroom, I made quick work of my evening ablutions. I took the drops of morphine and crawled into bed exhausted from my long day, confident that the tincture would continue to stave off the merciless sobbing.

I dreamed that Zeke had recovered from his injuries. In my dream we were on a picnic in Golden Gate Park. Zeke put his sandwich down and reached out his hand to touch my face. ‘I’ll never leave you, Sarah,’ he whispered to me. He morphed into someone different, someone who stroked my face, saying strange words I did not understand. I awoke, disoriented, not sure where I was.