Полная версия

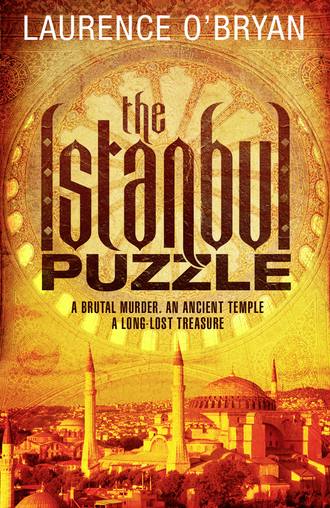

The Istanbul Puzzle

Was he joking? I’d imagined the local police in Oxford going around to the Institute, asking a few questions. Not a platoon of security service types trawling through every chapter of my life.

‘I told you,’ I said. ‘I’ve nothing to hide.’

The cabin was quiet except for the rumble of the plane’s engine.

‘So there’s nothing you want to tell us?’

‘Not a thing,’ I said, emphatically.

‘Very good,’ said Peter. The atmosphere changed from Artic cool to warmish again.

‘It’s the truth.’

‘I do hope so.’ He leaned back, drummed his fingers on the arm rest.

He clearly enjoyed playing games with people. I’d never liked people like that. Isabel seemed irritated too.

I looked out the window. I could see snow capped mountains far below. The sun was high in the sky. There was a blue shimmer of sea far off to our right. I got a strange feeling. That was where the landmass of Europe should have been.

What route were we taking?

‘Spectacular view, isn’t it?’ said Peter.

‘What mountains are they?’ I said.

‘Sorry, I’m no good at all that stuff. But they are beautiful, aren’t they?’

‘Now, about this mosaic,’ he said, in a softer tone. ‘I have to tell you there’s no record of such a mosaic anywhere in Istanbul or in all Turkey.’ He stretched his legs out into the passageway.

‘Which means it has to be from some undiscovered site. Mosaics were popular in the Roman Empire. They had to find a way to brighten their homes, I suppose.’ He sat up straighter.

‘I wonder what this old priest will tell us,’ said Peter.

Isabel brushed hair from her face.

‘Peter’s been busy trying to find out who was shooting at us last night,’ she said. Her tone made it sound as if she was trying to sell Peter to me.

‘Great, any news?’

‘A little,’ said Peter. ‘Somebody’s been trying to track the Consulate’s Range Rovers. That was what you were driving last night, Isabel, wasn’t it?’

Isabel nodded.

‘Well, someone went and hacked the systems at Istanbul’s Range Rover service centre early this morning. Whoever is after you is serious, Sean.’ He was looking out the window now.

‘What sort of people do this kind of thing?’ I said.

‘There are a number of small groups that might be involved. There are a lot of refugees in Istanbul. We’ve been keeping an eye on them, but it’s a big city and things are changing fast.’

He reached over, took an orange juice from the cooler bag and drank from it.

‘The Turks are blaming the whole thing on foreigners, of course.’ He gestured expansively. ‘They’re probably right.’

‘I’ll check what the news sites are saying,’ said Isabel.

She pulled a laptop from her briefcase, fired it up, hit a few keys, stared at the screen for a few minutes.

‘You don’t want to look at this.’

‘I want to.’

She passed the laptop to me. The browser window was filled with the BBC News website. The lead story, accompanied by a gruesome, but blurry image, was about Alek. What had happened to him was hitting the big time. I stared at the picture. It felt weird, as if I was watching someone else. This was too crazy.

Alek’s chin was down on his chest, his eyes hidden. He was strapped to a pillar. It was a still from that video I’d read about. I felt an urge to push the laptop away. I resisted. Then there was something catching in my throat. I put a hand to my mouth, kept it clamped shut as the sickening sensation passed. I wasn’t going to look away. That would be too easy.

The story underneath the picture read:

Beheading in Istanbul.

No one, so far, has claimed responsibility for the beheading of a Mr Alek Zegliwski, whose body was found in Istanbul on August 4. Turkish security experts are pointing the finger at a radical Islamic sect intent on the re-establishment of the Islamic Caliphate, which until 1924 was based at Hagia Sophia, where Mr Zegliwski was working. Re-establishing the Caliphate is a key goal for many Islamic fundamentalists.

The Arab script in the photo above Mr Zegliwski’s head, was, the article said, a threat to bring the war to London. Further on, the Turkish Prime Minister’s office had issued a statement saying arrests had been made that morning, and that the Turkish security services were following up a number of lines of enquiry.

‘This wasn’t supposed to happen,’ I said. I passed the laptop back to Isabel.

Peter took it, put it on his knee, read for a few minutes.

Then, he looked up from his screen and said, ‘The Turkish police raided known activists. They like to be seen to be taking action. I doubt they’ll find the people we’re looking for though.’ He nudged Isabel’s leg with the laptop. ‘Did you get a description of your friends from last night circulated?’

‘It was attached to my report,’ she said.

‘Was there anything about Alek’s behaviour in the past few weeks that seems odd now, Sean?’ Her tone was soft, coaxing.

I thought about her question as the queasy sensation from seeing that image of Alek slowly faded. ‘There’s nothing I can put a finger on. He was unavailable a few times, but that happened now and again with him.’ It was weird talking about Alek in this way.

Peter was drumming his fingers on his armrest.

Isabel looked out the window.

A flash of sunlight in the corner of my eye made me turn and stare out the window on the right. What I saw amazed me.

The glimmer of sea that I’d seen in the distance stretched to the horizon now, where the continent of Europe should have been, and in the sky, flying parallel with us, was a silver-grey jet fighter, no more than half a mile away. It had the distinctive dual tail-fins of the F-35 Lightning.

We were being escorted by a state-of-the-art fighter jet. But why? And where the hell were we?

Chapter 15

On the rounded top of a salt hill, an outcrop of the Zagros Mountains, a black-cloaked shepherd sat. His flock, fourteen thin black sheep, was foraging among skeletal dwarf oak trees. In the distance a layer of dust and pollution marked the location of the city of Mosul.

The Zagros mountain chain is a natural barrier between Iran and Iraq. It extends from north of the Straits of Hormuz all the way into Turkey. It’s a thousand miles long and its peaks are snow-capped. Its foothills resemble the hills of the US South West or the Highlands of Scotland. The city of Mosul, in the north of Iraq on the Tigris river, is near the ancient site of the city of Nineveh, capital of the Assyrian Empire. Uncounted armies have battled in this area.

The shepherd watched the white trail of a plane as it rose from Mosul airport. He thought about the warning he’d heard the night before. The evening star of Ishtar had risen late. The wizened crone who slept in a cave at the bottom of the hill had come into the village square to speak to them for the first time in ten years.

‘Not since Jonah warned the Ninevites has such a thing happened,’ she’d said in the pale evening light. Then she’d coughed for almost a minute.

Finally she’d continued, ‘Remember Jonah’s warning.’ She’d looked at every face. ‘Another great city will be destroyed.’

Chapter 16

‘That’s the easternmost corner of the Mediterranean,’ said Peter. ‘We’ll be heading inland soon, now that we’ve picked up our escort.’

‘What do we need an escort for?’ I was trying to sound as unfazed as I could. I turned, looked out the window again, just to check the F-35 was actually there.

‘We’ll be flying near the Syrian border soon, and with everything that’s been going on, we don’t want to take any chances. Thankfully, air cover is one of the few things we can still rely on here.’ He leaned back in his seat.

‘I should have told you we were making a stop before taking you to London,’ said Isabel, looking at me. ‘But I was asked not to.’ Her gaze flickered towards Peter.

A list of questions came into my mind. ‘Where are we going?’ was the one that came out.

‘Mosul,’ said Isabel.

‘Northern Iraq?’

She nodded. ‘The expert I told you about – Father Gregory – has been working on an archaeological dig not far from the city. We don’t have much choice, Sean, unless you want to wait a month until he finishes up there.’ Isabel sounded genuinely sorry she hadn’t told me what was going on.

If I remembered right, Mosul had been the scene of a number of bloody battles after Saddam’s fall.

‘Isn’t Mosul still a bit hot for archaeological work?’

Peter closed his eyes. ‘Mosul has been hot for a long time. The whole of Iraq is an archaeological minefield. Everyone has a different view about which layer of history is the most important and which you can trample on.’ He waved at Isabel. ‘Why don’t you tell him what we dug up?’

Isabel sat forward. ‘Mosul was the earliest Christian city outside what is now Israel,’ she said. ‘The reason Father Gregory is there is because the Greek Orthodox Church wants him to look at some very old Christian sites, before someone bans them from digging in the country. It’s not an ideal time to dig, but when is it around there?

‘Mosul has nearly as much history as Istanbul,’ said Peter. ‘It’s not far from the tar pits, which were the original source of Byzantium’s secret weapon, Greek fire, which saved their asses from the Muslim hordes. All of us might be worshipping Allah now, if the Greeks hadn’t won in 678 with the help of Greek fire.’

Suddenly, we dropped altitude. A gaping hole opened in my stomach. I looked out the window. I could see a range of grey mountains. One, far off, still had snow on its peak. To our right there were bare rolling hills stretching away into a yellowy horizon. Our altitude stabilised after about thirty seconds. Then our escort was alongside us again.

‘An evasive manoeuvre most likely,’ said Peter. ‘Some unknown radar signal must have lit us up.’

I continued staring out the window. Was this for real?

‘Can anyone just walk into Iraq these days?’ I said.

‘You can, if you have the right visa,’ said Peter. ‘The Iraqi Department of Border Security has a temporary visa programme for just this sort of occasion. And we have friends at Mosul airport. I don’t expect there’ll be a problem.’

He was right.

‘Welcome to the land of Gilgamesh,’ was how the green suited senior guard at the airport greeted us. His soft, educated accent seemed out of place after the guttural tones of the Iraqi guards who’d escorted us in a hot, white minibus from our plane to Mosul’s concrete airport terminal.

‘I lived in London for five years,’ he said, before he handed us back our passports.

‘Have a nice day!’ were the words that echoed after us as we crossed the passport hall.

And it was hot, brutally hot. The air was as thick as oil. There were air conditioning units on the walls of the terminal at various points, but for some reason they were turned off.

I felt a crawling sensation under my skin. There were guards standing around, but few travellers. And the guards were standing well back from us, as if they were waiting for someone to blow themselves up. They were all wearing ill-fitting green camouflage uniforms, with black patches on their arms with yellow lion head insignias on them, and soft peaked caps.

Within a minute of leaving the airport building my shirt clung to my skin as if I’d showered in cola.

We were being escorted towards a camouflaged Hummer by two young guards barely out of their teens, with tufts of wispy hair on their chins. The Hummer was parked beyond concrete barriers about two hundred yards from the terminal building. Peter was the only one of us who was carrying anything. He had a black Lowepro knapsack over one shoulder. Everything else was back on the plane.

The Hummer’s door opened as we came up to it. A man in a crumpled cream suit stepped halfway out, waved at us. Then he got back in.

When the Hummer’s doors closed behind us I understood why. The air inside was as cool as a refrigerator’s. It was like being in heaven, compared to the heat outside. I undid some shirt buttons, let the cool air slip over my skin.

‘Got any water?’ I said.

The man in the left-hand driving seat who’d waved at us, the only occupant of the vehicle, opened a black refrigerator box that sat in the front passenger footwell. He passed me a bottle of the coolest water I’d ever tasted.

As I took my first sip, I noticed he had put his hand on Isabel’s arm. She had climbed into the front seat next to him. She slapped his hand away.

‘Nice to see you too, my dear,’ said the man. The Hummer started with a roar.

‘Sean meet Mark Headsell, one of our…’ she hesitated, as if she was debating with herself how to say what he did, ‘representatives in Mosul.’ She spat out the word representative. ‘He’s an old friend.’

‘Good to meet you, Sean. Don’t mind Isabel. Welcome to the front line’

‘I thought the front line was in Afghanistan,’ I said.

‘We’re still busy here, I can tell you,’ said Mark.

Isabel was looking out the side window. Peter was outside on his phone. He was standing with his back to us.

He finished his call, jerked the door of the Hummer open. ‘How is your personal hellhole these days, Mark?’ he said, loudly. Then he slapped Mark’s shoulder.

‘Wonderful, if you don’t mind sewage pipes that back up, gun-toting locals with grudges, and fleas as big as rats.’

‘That sounds like progress,’ said Peter.

‘You’re heading for Magloub, right?’ said Mark. ‘Where that crazy Greek priest is digging?’

‘How long will it take to get there?’ said Peter.

‘Well, if we don’t get blown up or have to take a lot of stupid detours, we should be there in less than two hours. It’s only fifty miles or so.’

At the exit from the airport there was a checkpoint. It was manned by bearded security guards wearing the same yellow lion insignias. They also had black bulletproof vests on. Mark told us they were from a new Golden Lions security force that had taken over after the last US Marines had left. A sign nearby in English and Arabic read Deadly Force Area. After an exchange of words between Mark and one of the guards, we were waved on.

We travelled for a while in silence. I was soaking up the sights outside the tinted windows. The road from the airport was wide and dusty. There were one or two wrecks of houses, but most of the buildings looked untouched by the years of war. There was even some building work going on.

There were small craters on the road occasionally, probably where IEDs had gone off. We passed a big petrol station a few minutes after leaving the airport. It was surrounded by cement walls, except for a small entrance manned by security guards. There was a queue to get into it.

Then we passed a cluster of low houses at a crossroads. Some of them had sandbags piled haphazardly near their doors. One had a cement wall in front of it. They looked deserted.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.