полная версия

полная версияThe Witches of New York

Q. K. Philander Doesticks

The Witches of New York

Preface

What the Witches of New York City personally told me, Doesticks, you will find written in this volume, without the slightest exaggeration or perversion. I set out now with no intention of misrepresenting anything that came under my observation in collecting the material for this book, but with an honest desire to tell the simple truth about the people I encountered, and the prophecies I paid for.

So far from desiring to do any injustice to the Fortune Tellers of the Metropolis, I sincerely hope that my labors may avail something towards making their true deservings more widely appreciated, and their fitting reward more full and speedy. I am satisfied that so soon as their character is better understood, and certain peculiar features of their business more thoroughly comprehended by the public, they will meet with more attention from the dignitaries of the land than has ever before been vouchsafed them.

I thank the public for the flattering consideration paid to what I have heretofore written, and respectfully submit that if they would increase the obligation, perhaps the readiest way is to buy and read the present volume.

The Author.Sept. 20th, 1858.

CHAPTER I.

WHICH IS MERELY EXPLANATORY

Which is simply explanatory, so far as regards the book, but in which the author takes occasion to pay himself several merited compliments, on the score of honesty, ability, etcThe first undertaking of the author of these pages will be to convince his readers that he has not set about making a merely funny book, and that the subject of which he writes is one that challenges their serious and earnest attention. Whatever of humorous description may be found in the succeeding chapters, is that which grows legitimately out of certain features of the theme; for there has been no overstrained effort to make fun where none naturally existed.

The Witches of New York exert an influence too powerful and too wide-spread to be treated with such light regard as has been too long manifested by the community they have swindled for so many years; and it is to be desired that the day may come when they will be no longer classed with harmless mountebanks, but with dangerous criminals.

People, curious in advertisements, have often read the “Astrological” announcements of the newspapers, and have turned up their critical noses at the ungrammatical style thereof, and indulged the while in a sort of innocent wonder as to whether these transparent nets ever catch any gulls. These matter-of-fact individuals have no doubt often queried in a vague, purposeless way, if there really can be in enlightened New York any considerable number of persons who have faith in charms and love-powders, and who put their trust in the prophetic infallibility of a pack of greasy playing-cards. It may open the eyes of these innocent querists to the popularity of modern witchcraft to learn that the nineteen she-prophets who advertise in the daily journals of this city are visited every week by an average of sixteen hundred people, or at the rate of more than a dozen customers a day for each one; and of this immense number probably two-thirds place implicit confidence in the miserable stuff they hear and pay for.

It is also true that although a part of these visitors are ignorant servants, unfortunate girls of the town, or uneducated overgrown boys, still there are among them not a few men engaged in respectable and influential professions, and many merchants of good credit and repute, who periodically consult these women, and are actually governed by their advice in business affairs of great moment.

Carriages, attended by liveried servants, not unfrequently stop at the nearest respectable corner adjoining the abode of a notorious Fortune-Teller, while some richly-dressed but closely-veiled woman stealthily glides into the habitation of the Witch. Many ladies of wealth and social position, led by curiosity, or other motives, enter these places for the purpose of hearing their “fortunes told.” When these ladies are informed of the true character of the houses they have thus entered, and the real business of many of these women whose fortune-telling is but a screen to intercept the public gaze from it, it is not likely that any one of them will ever compromise her reputation by another visit.

People who do not know anything about the subject will perhaps be surprised to hear that most of these humbug sorceresses are now, or have been in more youthful and attractive days, women of the town, and that several of their present dens are vile assignation houses; and that a number of them are professed abortionists, who do as much perhaps in the way of child-murder as others whose names have been more prominently before the world; and they will be astonished to learn that these chaste sibyls have an understood partnership with the keepers of houses of prostitution, and that the opportunities for a lucrative playing into each other’s hands are constantly occurring.

The most terrible truth connected with this whole subject is the fact that the greater number of these female fortune-tellers are but doing their allotted part in a scheme by which, in this city, the wholesale seduction of ignorant, simple-hearted girls, in the lower walks of life, has been thoroughly systematized.

The fortune-teller is the only one of the organization whose operations may be known to the public; the other workers – the masculine go-betweens who lead the victims over the space intervening between her house and those of deeper shame – are kept out of sight and are unheard of. There is a straight path between these two points which is travelled every year by hundreds of betrayed young girls, who, but for the superstitious snares of the one, would never know the horrible realities of the other. The exact mode of proceeding adopted by these conspirators against virtue, the details of their plans, the various stratagems by which their victims are snared and led on to certain ruin, are not fit subjects for the present chapter; but any individual who is disposed to prosecute the inquiry for himself will find in the various police records much matter for his serious cogitation, and may there discover the exact direction in which to continue his investigations with the certainty of demonstrating these facts to his perfect satisfaction.

A few months ago, at the suggestion of the editor of one of the leading daily newspapers of America, a series of articles was written about the fortune-tellers of New York city, and these articles were in due time published in that journal, and attracted no little attention from its readers. These chapters, with such alterations as were requisite, and with many additions, form the bulk of this present volume.

The work has been conscientiously done. Every one of the fortune-tellers described herein was personally visited by the “Individual,” and the predictions were carefully noted down at the time, word for word; the descriptions of the necromantic ladies and their surroundings are accurate, and can be corroborated by the hundreds who have gone over the same ground before and since. They were treated in the most fair and frank manner; the same data as to time and date of birth, age, nationality, etc., were given in all cases, and the same questions were put to all, so that the absurd differences in their statements and predictions result from the unmitigated humbug of their pretended art, and from no misinformation or misrepresentation on the part of the seeker after mystic knowledge.

This latter person was perfectly unknown to the worthy ladies of the black art profession; he was to them simply an individual, one of the many-headed public, a cash customer, who paid liberally for all he required, and who, by reason of the dollars he disbursed, was entitled to the very best witchcraft in the market.

And he got it.

He undertook a few short journeys in search of the marvellous; he went on a couple of dozen voyages of discovery without going out of sight of home; he penetrated to the out-of-the-way regions, where the two-and-sixpenny witches of our own time grow. He got his fill of the cheap prophecy of the day, and procured of the oracles in person their oracularest sayings, at the very highest market price. For the business-like seers of this age are easily moved to prophesy by the sight of current moneys of the land, no matter who presents the same; whereas the oracles of the olden time dealt only with kings and princes, and nothing less than the affairs of an entire nation, or a whole territory, served to get their slow prophetic apparatus into working trim. To the necromancers of early days the anxieties of private individuals were as naught, and from the shekels of humble life they turned them contemptuously away.

It is probably a thorough conviction of the necessity of eating and drinking, and a constant contemplation from a Penitentiary point of view of the consequences of so doing without paying therefor, that induces our modern witches to charge a specific sum for the exercise of their art, and to demand the inevitable dollar in advance.

Whatever there is of Sorcery, Astrology, Necromancy, Prophecy, Fortune-telling, and the Black Art generally, practised at this time by the professional Witches of New York, is here honestly set down.

Should any other individual become particularly interested in the subject, and desire to go back of the present record and make his exploration personally among the Fortune-tellers, he will find their present addresses in the newspapers of the day, and can easily verify what is herein written.

With these remarks as to the intention of this book, the reader is referred by the Cash Customer to the succeeding chapters for further information. And the public will find in the advertisements, appended to the name and number of each mysteriously gifted lady, the pleasing assurance that she will be happy to see, not only the Cash Customer of the present writing, but also any and all other customers, equally cash, who are willing to pay the customary cash tribute.

CHAPTER II.

MADAME PREWSTER, No. 373 BOWERY

Is devoted to the glorification of Madame Prewster of No. 373 Bowery, the Pioneer Witch of New YorkThe “Individual” also herein bears his testimony that she is oily and water-proofThis woman is one of the most dangerous of all those in the city who are engaged in the swindling trade of Fortune Telling, and has been professionally known to the police and the public of New York for about fourteen years. The amount of evil she has accomplished in that time is incalculable, for she has been by no means idle, nor has she confined her attention even to what mischief she could work by the exercise of her pretended magic, but if the authenticity of the records may be relied on, she has borne a principal part in other illicit transactions of a much more criminal nature. She has been engaged in the “Witch” business in this city for more years than has any other one whose name is now advertised to the public.

If the history of her past life could be published, it would astound even this community, which is not wont to be startled out of its propriety by criminal development, for if justice were done, Madame Prewster would be at this time serving the State in the Penitentiary for her past misdoings; but, in some of these affairs of hers, men of so much respectability and political influence have been implicated, that, having sure reliance on their counsel and assistance, the Madame may be regarded as secure from punishment, even should any of her many victims choose to bring her into court.

The quality of her Witchcraft, by which she ostensibly lives, and the amount of faith to be reposed in her mystic predictions, may be seen from the history of a visit to her domicile, which is hereunto appended in the very words of the “Individual” who made it.

The “Cash Customer” makes his first Voyage in a Shower, but encounters an Oily and Waterproof Witch at the end of his Journey.

It rained, and it meant to rain, and it set about it with a will.

It was as if some “Union Thunderstorm Company” was just then paying its consolidated attention to the city and county of New York; or, as if some enterprising Yankee of hydraulic tendencies, had contracted for a second deluge and was hurrying up the job to get his money; or, as if the clouds were working by the job; or, as if the earth was receiving its rations of rain for the year in a solid lump; or, as if the world had made a half-turn, leaving in the clouds the ocean and rivers, and those auxiliaries to navigation were scampering back to their beds as fast as possible; or, as if there had been a scrub-race to the earth between a score or more full-grown rain storms, and they were all coming in together, neck-and-neck, at full speed.

Despite the juiciness of these opening sentences, the “Individual” does not propose to accompany the account of his heroical setting-forth on his first witch-journey with any inventory of natural scenery and phenomena, or with any interesting remarks on the wind and weather. Those who have a taste for that sort of thing will find in a modern circulating library, elaborate accounts of enough “dew-spangled grass” to make hay for an army of Nebuchadnezzars and a hundred troops of horse – of “bright-eyed daisies” and “modest violets,” enough to fence all creation with a parti-colored hedge – of “early larks” and “sweet-singing nightingales,” enough to make musical pot-pies and harmonious stews for twenty generations of Heliogabaluses; to say nothing of the amount of twaddle we find in American sensation books about “hawthorn hedges” and “heather bells,” and similar transatlantic luxuries that don’t grow in America, and never did.

And then the sunrises we’re treated to, and the sunsets we’re crammed with, and the “golden clouds,” the “grand old woods,” the “distant dim blue mountains,” the “crystal lakes,” the “limpid purling brooks,” the “green-carpeted meadows,” and the whole similar lot of affected bosh, is enough to shake the faith of a practical man in nature as a natural institution, and to make him vote her an artificial humbug.

So the voyager in pursuit of the marvellous, declines to state how high the thermometer rose or fell in the sun or in the shade, or whether the wind was east-by-north, or sou’-sou’-west by a little sou’.

The “dew on the grass” was not shining, for there was in his vicinity no dew and no grass, nor anything resembling those rural luxuries. Nor was it by any means at “early dawn;” on the contrary, if there be such a commodity in a city as “dawn,” either early or late, that article had been all disposed of several hours in advance of the period at which this chapter begins.

But at midday he set forth alone to visit that prophetess of renown, Madame Prewster. He was fully prepared to encounter whatever of the diabolical machinery of the black art might be put in operation to appal his unaccustomed soul.

But as he set forth from the respectable domicile where he takes his nightly roost, it rained, as aforementioned. The driving drops had nearly drowned the sunshine, and through the sickly light that still survived, everything looked dim and spectral. Unearthly cars, drawn by ghostly horses, glided swiftly through the mist, the intangible apparitions which occupied the drivers’ usual stands hailing passengers with hollow voices, and proffering, with impish finger and goblin wink, silent invitations to ride. Fantastic dogs sneaked out of sight round distant corners, or skulked miserably under phantom carts for an imaginary shelter. The rain enveloped everything with a grey veil, making all look unsubstantial and unreal; the human unfortunates who were out in the storm appeared cloudy and unsolid, as if each man had sent his shadow out to do his work and kept his substance safe at home.

The “Individual” travelled on foot, disdaining the miserable compromise of an hour’s stew in a steaming car, or a prolonged shower-bath in a leaky omnibus. Being of burly figure and determined spirit, he walked, knowing that his “too-solid flesh” would not be likely “to melt, thaw, and resolve itself into a dew,” and firmly believing that he was not born to be drowned.

He carried no umbrella, preferring to stand up and fight it out with the storm face to face, and because he detested a contemptible sneaking subterfuge of an umbrella, pretending to keep him dry, and all the time surreptitiously leaking small streams down the back of his neck, and filling his pockets with indigo colored puddles; and because, also, an umbrella would no more have protected a man against that storm, than a gun-cotton overcoat would have availed against the storm of fire that scorched old Sodom.

He placed his trust in a huge pair of water-proof boots, and a felt hat that shed water like a duck. He thrust his arms up to his elbows into the capacious pockets of his coat, drew his head down into the turned-up collar of that said garment, like a boy-bothered mud-turtle, and marched on.

With bowed head, set teeth, and sturdy step, the cash customer tramped along, astonishing the few pedestrians in the street by the energy and emphasis of his remarks in cases of collision, and attracting people to the windows to look at him as he splashed his way up the street. He minded them no more than he did the gentleman in the moon, but drove forward at his best speed, now breaking his shins over a dry-goods box, then knocking his head against a lamp-post; now getting a great punch in the stomach from an unexpected umbrella, then involuntarily gauging the depth of some unseen puddle, and then getting out of soundings altogether in a muddy inland sea; now swept almost off his feet by a sudden torrent of sufficient power to run a saw-mill, and only recovering himself to find that he was wrecked on the curbstone of some side street that he didn’t want to go to. At length, after a host of mishaps, including some interesting but unpleasant submarine explorations in an unusually large mud-hole into which he fell full-length, he arrived, soaked and savage, at the house of Madame Prewster.

This elderly and interesting lady has long been an oily pilgrim in this vale of tears. The oldest inhabitant cannot remember the exact period when this truly great prophetess became a fixture in Gotham, and began to earn her bread and butter by fortune-telling and kindred occupations. Her unctuous countenance and pinguid form are known to hundreds on whose visiting lists her name does not conspicuously appear, and to whom, in the way of business, she has made revelations which would astonish the unsuspecting and unbelieving world. She is neither exclusive nor select in her visitors. Whoever is willing to pay the price, in good money – a point on which her regulations are stringent – may have the benefit of her skill, as may be seen by her advertisement:

“Card. – Madame Prewster returns thanks to her friends and patrons, and begs to say that, after the thousands, both in this city and Philadelphia, who have consulted her with entire satisfaction, she feels confident that in the questions of astrology, love, and law matters, and books or oracles, as relied on constantly by Napoleon, she has no equal. She will tell the name of the future husband, and also the name of her visitors. No. 373 Bowery, between Fourth and Fifth streets.”

The undaunted seeker after mystic lore rang a peal on the astonished door-bell that created an instantaneous confusion of the startled inmates. There was a good deal of hustling about, and running hither, thither, and to the other place, before any one appeared; meantime, the dainty fingers of the damp customer performed other little solos on the daubed and sticky bell-pull, – and he also amused himself with inspection of, and comments on, the German-silver plate on the narrow panel, which bore the name of the illustrious female who occupied these domains.

At last the door was opened by a greasy girl, and the visitor was admitted to the hall, where he stood for a minute, like a fresh-water merman, “all dripping from the recent flood.”

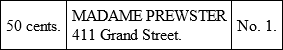

The juvenile female who had admitted him thus far, evidently took him for a disreputable character, and stood prepared to prevent depredations. She planted herself firmly before him in the narrow hall in an attitude of self-defence, and squaring off scientifically, demanded his business. Astrology was mentioned, whereupon the threatening fists were lowered, the saucy under-jaw was retracted, and the general air of pugnacity was subdued into a very suspicious demeanor, as if she thought he hadn’t any money, and wanted to storm the castle under false pretences. She informed him that before matters went any further, he must buy tickets, which she was prepared to furnish, on receipt of a dollar and a half; he paid the money, which transaction seemed to raise him in her estimation to the level of a man who might safely be trusted where there was nothing he could steal. One fist she still kept loaded, ready to instantly repel any attack which might be suddenly made by her designing enemy, the other hand cautiously departed petticoatward, and after groping about some time in a concealed pocket, produced from the mysterious depth a card, too dirty for description, on which these words were dimly visible:

The belligerent girl then led the way through a narrow hall, up two flights of stairs into a cold room, where she desired her visitor to be seated. She then carefully locked one or two doors leading into adjoining rooms, put the keys in her pocket, and departed. Before her exit she made a sly demonstration with her fists and feet, as if she was disposed to break the truce, commence hostilities, and punch his unprotected head, without regard to the laws of honorable warfare. She departed, however, at last, without violence, though the voyager could hear her pause on each landing, probably debating whether it wasn’t best after all to go back and thrash him before the opportunity was lost for ever.

This grand reception-room was an apartment about six feet by eight; it was uncarpeted, and was luxuriously furnished with six wooden chairs, one stove, with no spark of fire, one feeble table, one spittoon, and two coal-scuttles.

The view from the window was picturesque to a degree, being made up of cats, clothes-lines, chimneys, and crockery, and occasionally, when the storm lifted, a low roof near by suggested stables. The odor which filled the air had at least the merit of being powerful, and those to whose noses it was grateful, could not complain that they did not get enough of it. Description must necessarily fall far short of the reality, but if the reader will endeavor to imagine a couple of oil-mills, a Peck-slip ferry-boat, a soap-and-candle manufactory, and three or four bone-boiling establishments being simmered together over a slow fire in his immediate vicinity, he may possibly arrive at a faint and distant notion of the greasy fragrance in which the abode of Madame Prewster is immersed.

For an hour and a half by the watch of the Cash Customer (which being a cheap article, and being alike insensible to the voice of reason and the persuasions of the watchmaker, would take its own time to do its work, and the long hands of which generally succeeded in getting once round the dial in about eighty minutes) was this too damp individual incarcerated in the room by the order of the implacable Madame Prewster.

He would long before the end of that time have forfeited his dollar and a half and beaten an inglorious retreat, but that he feared an ambuscade and a pitching-into at the fair hands of the warlike servant.

Finally, this last-named individual came to the rescue, and conducted him by a circuitous route, and with half-suppressed demonstrations of animosity, to the basement. This room was evidently the kitchen, and was fitted up with the customary iron and brazen apparatus.

A feeble child, just old enough to run alone, had constructed a child’s paradise in the lee of the cooking-stove, and was seated on a dinner-pot, with one foot in a saucepan; it had been playing on the wash-boiler like a drum, but was now engaged in decorating some loaves of unbaked bread with bits of charcoal and splinters from the broom.