полная версия

полная версияHistory of Cuba: or, Notes of a Traveller in the Tropics

The three great staples of production and exportation are sugar, coffee and tobacco. The sugar-cane (arundo saccharifera) is the great source of the wealth of the island. Its culture requires, as we have remarked elsewhere, large capital, involving as it does a great number of hands, and many buildings, machines, teams, etc. We are not aware that any attempt has ever been made to refine it on the island. The average yield of a sugar plantation affords a profit of about fifteen per cent. on the capital invested. Improved culture and machinery have vastly increased the productiveness of the sugar plantations. In 1775 there were four hundred and fifty-three mills, and the crops did not yield quite one million three hundred thousand arrobas (an arroba is twenty-five pounds). Fifty years later, a thousand mills produced eight million arrobas; that is to say, each mill produced six times more sugar. The Cuban sugar has the preference in all the markets of Europe. Its manufacture yields, besides, molasses, which forms an important article of export. A liquor, called aguadiente, is manufactured in large quantities from the molasses. There are several varieties of cane cultivated on the island. The Otaheitian cane is very much valued. A plantation of sugar-cane requires renewal once in about seven years. The canes are about the size of a walking-stick, are cut off near the root, and laid in piles, separated from the tops, and then conveyed in carts to the sugar-mill, where they are unladen. Women are employed to feed the mills, which is done by throwing the canes into a sloping trough, from which they pass between the mill-stones and are ground entirely dry. The motive power is supplied either by mules and oxen, or by steam. Steam machinery is more and more extensively employed, the best machines being made in the vicinity of Boston. The dry canes, after the extraction of the juice, are conveyed to a suitable place to be spread out and exposed to the action of the sun; after which they are employed as fuel in heating the huge boilers in which the cane-juice is received, after passing through the tank, where it is purified, lime-water being there employed to neutralize any free acid and separate vegetable matters. The granulation and crystallization is effected in large flat pans. After this, it is broken up or crushed, and packed in hogsheads or boxes for exportation. A plantation is renewed by laying the green canes horizontally in the ground, when new and vigorous shoots spring up from every joint, exhibiting the almost miraculous fertility of the soil of Cuba under all circumstances.

The coffee-plant (caffea Arabica) is less extensively cultivated on the island than formerly, being found to yield only four per cent. on the capital invested. This plant was introduced by the French into Martinique in 1727, and made its appearance in Cuba in 1769. It requires some shade, and hence the plantations are, as already described, diversified by alternate rows of bananas, and other useful and ornamental tropical shrubs and trees. The decadence of this branch of agriculture was predicted for years before it took place, the fall of prices being foreseen; but the calculations of intelligent men were disregarded, simply because they interfered with their own estimate of profits. When the crash came, many coffee raisers entirely abandoned the culture, while the wiser among them introduced improved methods and economy into their business, and were well rewarded for their foresight and good judgment. The old method of culture was very careless and defective. The plants were grown very close together, and subjected to severe pruning, while the fruit, gathered by hand, yielded a mixture of ripe and unripe berries. In the countries where the coffee-plant originated, a very different method is pursued. The Arabs plant the trees much further apart, allow them to grow to a considerable height, and gather the crop by shaking the trees, a method which secures only the ripe berries. A coffee plantation managed in this way, and combined with the culture of vegetables and fruits on the same ground, would yield, it is said, a dividend of twelve per cent. on the capital employed; but the Cuban agriculturists have not yet learned to develop the resources of their favored island.

Tobacco. This plant (nicotiana tabacum) is indigenous to America, but the most valuable is that raised in Cuba. Its cultivation is costly, for it requires a new soil of uncommon fertility, and a great amount of heat. It is very exhausting to the land. It does not, it is true, require much labor, nor costly machinery and implements. It is valued according to the part of the island in which it grows. That of greatest value and repute, used in the manufacture of the high cost cigars, is grown in the most westerly part of the island, known popularly as the Vuelta de Abajo. But the whole western portion of the island is not capable of producing tobacco of the best quality. The region of superior tobacco is comprised within a parallelogram of twenty-nine degrees by seven. Beyond this, up to the meridian of Havana, the tobacco is of fine color, but inferior aroma (the Countess Merlin calls this aroma the vilest of smells); and the former circumstance secures it the preference of foreigners. From Consolacion to San Christoval, the tobacco is very hot, in the language of the growers, but harsh and strong, and from San Christoval to Guanajay, with the exception of the district of Las Virtudes, the tobacco is inferior, and continues so up to Holguin y Cuba, where we find a better quality. The fertile valley of Los Guines produces poor smoking tobacco, but an article excellent for the manufacture of snuff. On the banks of the Rio San Sebastian are also some lands which yield the best tobacco in the whole island. From this it may be inferred how great an influence the soil produces on the good quality of Cuban tobacco; and this circumstance operates more strongly and directly than the slight differences of climate and position produced by immediate localities. Perhaps a chemical analysis of the soils of the Vuelta de Abajo would enable the intelligent cultivator to supply to other lands in the island the ingredients wanting to produce equally good tobacco. The cultivators in the Vuelta de Abajo are extremely skilful, though not scientific. The culture of tobacco yields about seven per cent. on the capital invested, and is not considered to be so profitable on the island as of yore.

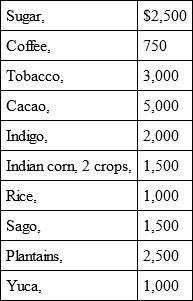

Cacao, rice, plantains, indigo, cotton, sago, yuca (a farinaceous plant, eaten like potatoes), Indian corn, and many other vegetable productions, might be cultivated to a much greater extent and with larger profit than they yield. We are astonished to find that with the inexhaustible fertility of the soil, with an endless summer, that gives the laborer two and three crops of some articles a year, agriculture generally yields a lower per centage than in our stern northern latitudes. The yield of a caballeria (thirty-two and seven-tenths acres) is as follows:

It must be remembered that there are multitudes of fruits and vegetable productions not enumerated above, which do not enter into commerce, and which grow wild. No account is taken of them. In the hands of a thrifty population, Cuba would blossom like a rose, as it is a garden growing wild, cultivated here and there in patches, but capable of supporting in ease a population of ten times its density.

About the coffee plantations, and, indeed, throughout the rural parts of the island, there is an insect called a cucullos, answering in its nature to our fire-fly, though quadruple its size, which floats in phosphorescent clouds over the vegetation. One at first sight is apt to compare them to a shower of stars. They come in multitudes, immediately after the wet or rainy season sets in, and there is consequently great rejoicing among the slaves and children, as well as children of a larger growth. They are caught by the slaves and confined in tiny cages of wicker, giving them sufficient light for convenience in their cabins at night, and, indeed, forming all the lamps they are permitted to have. Many are brought into the city and sold by the young Creoles, a half-dozen for a paseta (twenty-five cents). Ladies not unfrequently carry a small cage of silver attached to their bracelets, containing four or five of them, and the light thus emitted is like a candle. Some ladies wear a belt of them at night, ingeniously fastened about the waist, and sometimes even a necklace, the effect thus produced being highly amusing. In the ball-rooms they are sometimes worn in the flounces of the ladies' dresses, and they seem nearly as brilliant as diamonds. Strangely enough, there is a natural hook near the head of the Cuban fire-fly, by which it can be attached to any part of the dress without any apparent injury to the insect itself; this the writer has seen apparently demonstrated, though, of course, it could not be strictly made clear. The town ladies pet these cucullos, and feed them regularly with sugar cane, of which the insects partake with infinite relish; but on the plantations, when a fresh supply is wanted, they have only to wait until the twilight deepens, and a myriad can be secured without trouble.

The Cubans have a queer, but yet excellent mode of harnessing their oxen, similar to that still in vogue among eastern countries. The yoke is placed behind the horns, at the roots, and so fastened to them with thongs that they draw, or, rather, push by them, without chafing. The animals always have a hole perforated in their nostrils, through which a rope is passed, serving as reins, and rendering them extremely tractable; the wildest and most stubborn animals are completely subdued by this mode of controlling them, and can be led unresisting anywhere. This mode of harnessing seems to enable the animal to bring more strength to bear upon the purpose for which he is employed, than when the yoke is placed, as is the case with us, about the throat and shoulders. It is laid down in natural history that the greatest strength of horned animals lies in the head and neck, but, in placing the yoke on the breast, we get it out of reach of both head and neck, and the animal draws the load behind by the mere force of the weight and impetus of body, as given by the limbs. Wouldn't it be worth while to break a yoke of steers to this mode, and test the matter at the next Connecticut ploughing-match? We merely suggest the thing.

The Cuban horse deserves more than a passing notice in this connection. He is a remarkably valuable animal. Though small and delicate of limb, he can carry a great weight; and his gait is a sort of march, something like our pacing horses, and remarkably easy under the saddle. They have great power of endurance, are small eaters, and very docile and easy to take care of. The Montero inherits all the love of his Moorish ancestors for the horse, and never stirs abroad without him. He considers himself established for life when he possesses a good horse, a sharp Toledo blade, and a pair of silver spurs, and from very childhood is accustomed to the saddle. They tell you long stories of their horses, and would make them descended direct from the Kochlani,45 if you will permit them. Their size may readily be arrived at from the fact that they rarely weigh over six hundred pounds; but they are very finely proportioned.

The visitor, as he passes inland, will frequently observe upon the fronts of the clustering dwelling-houses attempts at representations of birds and various animals, looking like anything but what they are designed to depict, the most striking characteristic being the gaudy coloring and remarkable size. Pigeons present the colossal appearance of ostriches, and dogs are exceedingly elephantine in their proportions. Especially in the suburbs of Havana may this queer fancy be observed to a great extent, where attempts are made to depict domestic scenes, and the persons of either sex engaged in appropriate occupations. If such ludicrous objects were met with anywhere else but in Cuba, they would be called caricatures, but here they are regarded with the utmost complacency, and innocently considered as ornamental.46 Somehow this is a very general passion among the humbler classes, and is observable in the vicinity of Matanzas and Cardenas, as well as far inland, at the small hamlets. The exterior of the town houses is generally tinted blue, or some brown color, to protect the eyes of the inhabitants from the powerful reflection of the ever-shining sun.

One of the most petty and annoying experiences that the traveller upon the island is sure to meet with, is the arbitrary tax of time, trouble and money to which he is sure to be subjected by the petty officials of every rank in the employment of government; for, by a regular and legalized system of arbitrary taxation upon strangers, a large revenue is realized. Thus, the visitor is compelled to pay some five dollars for a landing permit, and a larger sum, say seven dollars, to get away again. If he desires to pass out of the city where he has landed, a fresh permit and passport are required, at a further expense, though you bring one from home signed by the Spanish consul of the port where you embarked, and have already been adjudged by the local authorities. Besides all this, you are watched, and your simplest movements noted down and reported daily to the captain of police, who takes the liberty of stopping and examining all your newspapers, few of which are ever permitted to be delivered to their address; and, if you are thought to be a suspicious person, your letters, like your papers, are unhesitatingly devoted to "government purposes."

An evidence of the jealous care which is exercised to prevent strangers from carrying away any information in detail relative to the island, was evinced to the writer in a tangible form on one occasion in the Paseo de Isabella. A young French artist had opened his portfolio, and was sketching one of the prominent statues that grace the spot, when an officer stepped up to him, and, taking possession of his pencil and other materials, conducted him at once before some city official within the walls of Havana. Here he was informed that he could not be allowed to sketch even a tree without a permit signed by the captain-general. As this was the prominent object of the Frenchman's visit to the island, and as he was really a professional artist sketching for self-improvement, he succeeded, after a while, in convincing the authorities of these facts, and he was then, as a great favor, supplied with a permit (for which he was compelled to pay an exorbitant fee), which guaranteed to him the privilege of sketching, with certain restrictions as to fortifications, military posts, and harbor views; the same, however, to expire after ninety days from the date.

The great value and wealth of the island has been kept comparatively secret by this Japan-like watchfulness; and hence, too, the great lack of reliable information, statistical or otherwise, relating to its interests, commerce, products, population, modes and rates of taxation, etc. Jealous to the very last degree relative to the possession of Cuba, the home government has exhausted its ingenuity in devising restrictions upon its inhabitants; while, with a spirit of avarice also goaded on by necessity, it has yearly added to the burthen of taxation upon the people to an unparalleled extent. The cord may be severed, and the overstrained bow will spring back to its native and upright position! The Cubans are patient and long-suffering, that is sufficiently obvious to all; and yet Spain may break the camel's back by one more feather!

The policy that has suppressed all statistical information, all historical record of the island, all accounts of its current prosperity and growth, is a most short-sighted one, and as unavailing in its purpose as it would be to endeavor to keep secret the diurnal revolutions of the earth. No official public chart of the harbor of Havana has ever been issued by the Spanish government, no maps of it given by the home government as authentic; they would draw a screen over this tropical jewel, lest its dazzling brightness should tempt the cupidity of some other nation. All this effort at secrecy is little better than childishness on their part, since it is impossible, with all their precautions, to keep these matters secret. It is well known that our war department at Washington contains faithful sectional and complete drawings of every important fortification in Cuba, and even the most reliable charts and soundings of its harbors, bays and seaboard generally.

The political condition of Cuba is precisely what might be expected of a Castilian colony thus ruled, and governed by such a policy. Like the home government, she presents a remarkable instance of stand-still policy; and from one of the most powerful kingdoms, and one of the most wealthy, is now the humblest and poorest. Other nations have labored and succeeded in the race of progress, while her adherence to ancient institutions, and her dignified scorn of "modern innovations," amount in fact to a species of retrogression, which has placed her far below all her sister governments of Europe. The true Hidalgo spirit, which wraps itself up in an antique garb, and shrugs its shoulders at the advance of other countries, still rules over the beautiful realm of Ferdinand and Isabella, and its high-roads still boast their banditti and worthless gipsies, as a token of the declining power of the Castilian crown.

CHAPTER XII

TACON'S SUMMARY MODE OF JUSTICEProbably of all the governors-general that have filled the post in Cuba none is better known abroad, or has left more monuments of his enterprise, than Tacon. His reputation at Havana is of a somewhat doubtful character; for, though he followed out with energy the various improvements suggested by Aranjo, yet his modes of procedure were so violent, that he was an object of terror to the people generally, rather than of gratitude. He vastly improved the appearance of the capital and its vicinity, built the new prison, rebuilt the governor's palace, constructed a military road to the neighboring forts, erected a spacious theatre and market-house (as related in connection with Marti), arranged a new public walk, and opened a vast parade ground without the city walls, thus laying the foundation of the new city which has now sprung up in this formerly desolate suburb. He suppressed the gaming-houses, and rendered the streets, formerly infested with robbers, as secure as those of Boston or New York. But all this was done with a bold military arm. Life was counted of little value, and many of the first people fell before his orders.

Throughout all his career, there seemed ever to be within him a romantic love of justice, and a desire to administer it impartially; and some of the stories, well authenticated, illustrating this fact, are still current in Havana. One of these, as characteristic of Tacon and his rule, is given in this connection, as nearly in the words of the narrator as the writer can remember them, listened to in "La Dominica's."

During the first year of Tacon's governorship, there was a young Creole girl, named Miralda Estalez, who kept a little cigar-store in the Calle de Mercaderes, and whose shop was the resort of all the young men of the town who loved a choicely-made and superior cigar. Miralda was only seventeen, without mother or father living, and earned an humble though sufficient support by her industry in the manufactory we have named, and by the sales of her little store. She was a picture of ripened tropical beauty, with a finely rounded form, a lovely face, of soft, olive tint, and teeth that a Tuscarora might envy her. At times, there was a dash of languor in her dreamy eye that would have warmed an anchorite; and then her cheerful jests were so delicate, yet free, that she had unwittingly turned the heads, not to say hearts, of half the young merchants in the Calle de Mercaderes. But she dispensed her favors without partiality; none of the rich and gay exquisites of Havana could say they had ever received any particular acknowledgment from the fair young girl to their warm and constant attention. For this one she had a pleasant smile, for another a few words of pleasing gossip, and for a third a snatch of a Spanish song; but to none did she give her confidence, except to young Pedro Mantanez, a fine-looking boatman, who plied between the Punta and Moro Castle, on the opposite side of the harbor.

Pedro was a manly and courageous young fellow, rather above his class in intelligence, appearance and associations, and pulled his oars with a strong arm and light heart, and loved the beautiful Miralda with an ardor romantic in its fidelity and truth. He was a sort of leader among the boatmen of the harbor for reason of his superior cultivation and intelligence, and his quick-witted sagacity was often turned for the benefit of his comrades. Many were the noble deeds he had done in and about the harbor since a boy, for he had followed his calling of a waterman from boyhood, as his fathers had done before him. Miralda in turn ardently loved Pedro; and, when he came at night and sat in the back part of her little shop, she had always a neat and fragrant cigar for his lips. Now and then, when she could steal away from her shop on some holiday, Pedro would hoist a tiny sail in the prow of his boat, and securing the little stern awning over Miralda's head, would steer out into the gulf, and coast along the romantic shore.

There was a famous roué, well known at this time in Havana, named Count Almonte, who had frequently visited Miralda's shop, and conceived quite a passion for the girl, and, indeed, he had grown to be one of her most liberal customers. With a cunning shrewdness and knowledge of human nature, the count besieged the heart of his intended victim without appearing to do so, and carried on his plan of operations for many weeks before the innocent girl even suspected his possessing a partiality for her, until one day she was surprised by a present from him of so rare and costly a nature as to lead her to suspect the donor's intentions at once, and to promptly decline the offered gift. Undismayed by this, still the count continued his profuse patronage in a way to which Miralda could find no plausible pretext of complaint.

At last, seizing upon what he considered a favorable moment, Count Almonte declared his passion to Miralda, besought her to come and be the mistress of his broad and rich estates at Cerito, near the city, and offered all the promises of wealth, favor and fortune; but in vain. The pure-minded girl scorned his offer, and bade him never more to insult her by visiting her shop. Abashed but not confounded, the count retired, but only to weave a new snare whereby he could entangle her, for he was not one to be so easily thwarted.

One afternoon, not long after this, as the twilight was settling over the town, a file of soldiers halted just opposite the door of the little cigar-shop, when a young man, wearing a lieutenant's insignia, entered, and asked the attendant if her name was Miralda Estalez, to which she timidly responded.

"Then you will please to come with me."

"By what authority?" asked the trembling girl.

"The order of the governor-general."

"Then I must obey you," she answered; and prepared to follow him at once.

Stepping to the door with her, the young officer directed his men to march on; and, getting into a volante, told Miralda they would drive to the guard-house. But, to the surprise of the girl, she soon after discovered that they were rapidly passing the city gates, and immediately after were dashing off on the road to Cerito. Then it was that she began to fear some trick had been played upon her; and these fears were soon confirmed by the volante's turning down the long alley of palms that led to the estate of Count Almonte. It was in vain to expostulate now; she felt that she was in the power of the reckless nobleman, and the pretended officer and soldiers were his own people, who had adopted the disguise of the Spanish army uniform.

Count Almonte met her at the door, told her to fear no violence, that her wishes should be respected in all things save her personal liberty, – that he trusted, in time, to persuade her to look more favorably upon him, and that in all things he was her slave. She replied contemptuously to his words, and charged him with the cowardly trick by which he had gained control of her liberty. But she was left by herself, though watched by his orders at all times to prevent her escape.