полная версия

полная версияChristine: A Fife Fisher Girl

All good dancing is beautiful, and it never requires immodesty, is indeed spoiled by any movement in this direction. However, as my fisher company danced modestly and gracefully, rendering naturally the artistic demands of the music, there is no necessity to pursue the subject. As the night wore on, the dancing became more enthusiastic, and graceful gestures were flung in, and little inspiring cries flung out, and often when the fiddles stopped, the happy feet went on for several bars without the aid of music.

Thus alternately telling stories, singing, and dancing, they passed the happy hours, mingling something of heart, and brain, and body, in all they did; and the midnight found them unwearied and good-tempered. Angus had behaved beautifully. Having made himself “Hail! Well met!” with the company, he forgot for the time that he was Master of Ballister, and entered into the happy spirit of the occasion with all the natural gayety of youth.

As he had dined with Faith Balcarry, he danced with her several times; and no one could tell the pride and pleasure in the girl’s heart. Then Christine introduced to her a young fisherman from Largo town, and he liked Faith’s slender form, and childlike face, and fell truly in love with the lonely girl, and after this night no one ever heard Faith complain that she had no one to love, and that no one loved her. This incident alone made Christine very happy, for her heart said to her that it was well worth while.

Cluny was the only dissatisfied person present, but then nothing would have satisfied Cluny but Christine’s undivided attention. She told him he was “unreasonable and selfish,” and he went home with his grandmother, in a pet, and did not return.

“He’s weel enough awa’,” said Christine to Faith. “If he couldna leave his bad temper at hame, he hadna ony right to bring it here.”

Of course it was not possible for Christine to avoid all dancing with Angus, but he was reasonable and obedient, and danced cheerfully with all the partners she selected, and in return she promised to walk home in his company. He told her it was “a miraculous favor,” and indeed he thought so. For never had she looked so bewilderingly lovely. Her beauty appeared to fill the room, and the calm, confident authority with which she ordered and decided events, touched him with admiring astonishment. What she would become, when he gave her the opportunity, he could not imagine.

At nine o’clock there was a sideboard supper from a long table at one side of the hall, loaded with cold meats, pastry, and cake. Every young man took what his partner desired, and carried it to her. Then when the women were served, the men helped themselves, and stood eating and talking with the merry, chattering groups for a pleasant half-hour, which gave to the last dances and songs even more than their early enthusiasm. Angus waited on Christine and Faith, and Faith’s admirer had quite a flush of vanity, in supposing himself to have cut the Master of Ballister out. He flattered himself thus, and Faith let him think so, and Christine shook her head, and called him “plucky and gay,” epithets young men never object to, especially if they know they are neither the one nor the other.

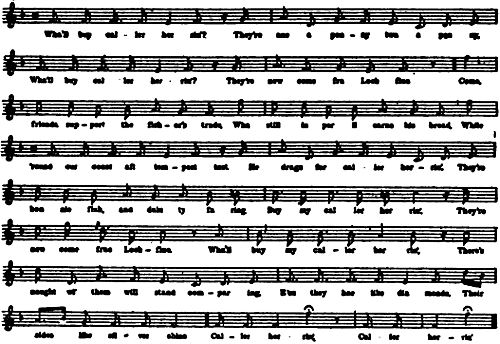

At twelve o’clock Ruleson spoke to the musicians, and the violins dropped from the merry reel of “Clydeside Lasses” into the haunting melody of “Caller Herrin’,” and old and young stood up to sing it. Margot started the “cry” in her clear, clarion-like voice; but young and old joined in the imperishable song, in which the “cry” is vocalized:

Who’ll buy cal-ler her-rin’? They’re twa a pen-ny twa a pen-ny,

Who’ll buy cal-ler her-rin’? They’re new come fra Loch fine. Come friends sup-port the fish-er’s trade. Wha still in yer’ll earns his bread. While

’round our coast aft tem-pest tost. He drags for cal-ler her-rin’. They’re bon-nie fish, and dain-ty fa-ring. Buy my cal-ler her-rin’. They’re new come frae Loch-flae. Who’ll buy my cal-ler her-rin’. There’s nought wi’ them will stand com-par-ing. E’en they hae like dia-monds. Their sides like sil-ver shine. Cal-ler her-rin’, Cal-ler her-rin’

At one o’clock the Fishers’ Hall was dark and still, and the echo of a tender little laugh or song from some couple, who had taken the longest way round for the nearest way home, was all that remained of the mirth and melody of the evening. Angus and Christine sauntered slowly through the village. The young man was then passionately importunate in the protestations of his love. He wooed Christine with all the honeyed words that men have used to the Beloved Woman, since the creation. And Christine listened and was happy.

At length, however, he was obliged to tell her news he had delayed as long as it was possible.

“Christine,” he said. “Dear Christine, I am going with my Uncle Ballister to the United States. We intend to see both the northern and southern states, and in California shall doubtless find the ways and means to cross over to China and Japan, and at Hongkong get passage for India, and then – ”

“And then whar next?”

“Through Europe to England. I dare say the journey will take us a whole year.”

“Mair likely twa or even three years. Whatna for are you going?”

“Because my uncle is going, and he is set on having me with him.”

“I wouldn’t wonder. Maybe he is going just for your sake. Weel I hope you’ll hae a brawly fine time, and come hame the better for it.”

“I cannot tell how I am to do without seeing you, for a whole year.”

“Folk get used to doing without, vera easy, if the want isn’t siller. Love isna a necessity.”

“O, but it is! Dear Christine, it is the great necessity.”

“Weel, I’m not believing it.”

Then they were at the foot of the hill on which Ruleson’s house stood, and Christine said, “Your carriage is waiting for you, Angus, and you be to bid me good night, here. I would rather rin up the hill by mysel’, and nae doubt the puir horses are weary standin’ sae lang. Sae good night, and good-by, laddie!”

“I shall not leave you, Christine, until I have seen you safely home.”

“I am at hame here. This is Ruleson’s hill, and feyther and mither are waiting up for me.”

A few imperative words from Angus put a stop to the dispute, and he climbed the hill with her. He went as slowly as possible, and told her at every step how beautiful she was, and how entirely he loved her. But Christine was not responsive, and in spite of his eloquent tenderness, they felt the chill of their first disagreement. When they came in sight of the house, they saw that it was dimly lit, and Christine stood still, and once more bade him good-by.

Angus clasped both her hands in his. “My love! My love!” he said. “If I spoke cross, forgive me.”

“I hae naething to forgive. I owe you for mair pleasure and happiness, than I can ever return.”

“Give me one kiss of love and forgiveness, Christine. Then I will know you love Angus” – and he tried gently to draw her closer to him. “Just one kiss, darling.”

“Na! Na,” she answered. “That canna be. I’m a fisher-lass, and we hae a law we dinna break – we keep our lips virgin pure, for the lad we mean to marry.”

“You are very hard and cruel. You send me away almost broken-hearted. May I write to you?”

“If you’ll tell me about a’ the wonderfuls you see, I’ll be gey glad to hear from you.”

“Then farewell, my love! Do not forget me!”

“It’s not likely I’ll forget you,” and her voice trembled, as she whispered “Farewell!” and gave him her hand. He stooped, and kissed it. Then he turned away.

She watched him till in the dim distance she saw him raise his hat and then disappear. Still she stood, until the roll of the carriage wheels gradually became inaudible. Then she knew that she was weeping, and she wiped her eyes, and turned them upon the light in the cottage burning for her. And she thought tenderly of her lover, and whispered to her heart – “If he had only come back! I might hae given him a kiss. Puir laddie! Puir, dear laddie! His uncle has heard tell o’ the fisher-lassie, and he’s ta’en him awa’ from Christine – but he’s his ain master – sae it’s his ain fault! Christine is o’er gude for anyone who can be wiled awa’ by man, or woman, or pleasure, or gold. I’ll be first, or I’ll be naething at a’!”

She found her father alone, and wide awake. “Where is Mither?” she asked.

“I got her to go to bed. She was weary and full o’ pain. Keep a close watch on your mither, Christine. The trouble in her heart grows warse, I fear. Wha was wi’ you in your hame-comin’?”

“Angus Ballister.”

“Weel, then?”

“It is the last time he will be wi’ me.”

“Is that sae? It is just as weel.”

“He is awa’ wi’ his Uncle Ballister, for a year or mair.”

“Is he thinking you’ll wait, while he looks o’er the women-folk in the rest o’ the warld?”

“It seems sae.”

“You liked him weel enough?”

“Whiles – weel enough for a lover on trial. But what would a lass do wi’ a husband wha could leave her for a year on his ain partic’lar pleasure.”

“I kent you wad act wiselike, when the time came to act. There’s nae men sae true as fishermen. They hae ane dear woman to love, and she’s the only woman in the warld for them. Now Cluny – ”

“We willna speak o’ Cluny, Feyther. Both you and Mither, specially Mither, are far out o’ your usual health. What for did God gie you a daughter, if it wasna to be a comfort and help to you, when you needed it? I’m no carin’ to marry any man.”

“Please God, you arena fretting anent Angus?”

“What for would I fret? He was a grand lover while he lasted. But when a man is feared to honor his love with his name, a lass has a right to despise him.”

“Just sae! But you mustna fret yoursel’ sick after him.”

“Me! Not likely!”

“He was bonnie enou’, and he had siller – plenty o’ siller!”

“I’m no’ thinkin’ o’ the siller, Feyther! Na, na, siller isn’t in the matter, but —

“When your lover rins over the sea,He may never come back again;But this, or that, will na matter to me,For my heart! My heart is my ain!”“Then a’s weel, lassie. I’ll just creep into Neil’s bed, for I dinna want to wake your mither for either this, or that, or ony ither thing. Good night, dearie! You’re a brave lassie! God bless you!”

CHAPTER V

CHRISTINE AND ANGUS

They did not separate, as if nothing had happened.

A sorrow we have looked in the face, can harm us no more.

Perhaps Christine was not so brave as her father thought, but she had considered the likelihood of such a situation, and had decided that there was no dealing with it, except in a spirit of practical life. She knew, also, that in the long run sentiment would have to give way to common sense, and the more intimate she became with the character of Angus Ballister, the more certain she felt that his love for her would have to measure itself against the pride and will of his uncle, and the tyranny of social estimates and customs.

She was therefore not astonished that Angus had left both himself and her untrammeled by promises. He was a young man who never went to meet finalities, especially if there was anything unpleasant or serious in them; and marriage was a finality full of serious consequences, even if all its circumstances were socially proper. And what would Society say, if Angus Ballister made a fisher-girl his wife!

“I wasna wise to hae this, or that, to do wi’ the lad,” she whispered, and then after a few moments’ reflection, she added, “nor was I altogether selfish i’ the matter. Neil relied on me making a friend o’ him, and Mither told me she knew my guid sense wad keep the lad in his proper place. Weel, I hae done what was expected o’ me, and what’s the end o’ the matter, Christine? Ye hae a sair heart, lass, an’ if ye arena in love wi’ a lad that can ne’er mak’ you his wife, ye are precariously near to it.” Then she was silent, while lacing her shoes, but when this duty was well finished, she continued, “The lad has gien me many happy hours, and Christine will never be the one to say, or even think, wrang o’ him; we were baith in the fault – if it be a fault – as equally in the fault, as the fiddle and the fiddlestick are in the music. Weel, then what’s to do? Duty stands high above pleasure, an’ I must gie my heart to duty, an’ my hands to duty, even if I tread pleasure underfoot in the highway in the doin’ o’ it.”

As she made these resolutions, some strong instinctive feeling induced her to dress herself in clean clothing from head to feet, and then add bright touches of color, and the glint of golden ornaments to her attire. “I hae taken a new mistress this morning,” she said, as she clasped her gold beads around her white throat – “and I’ll show folk that I’m not fretting mysel’ anent the auld one.” And in some unreasoning, occult way, this fresh, bright clothing strengthened her.

Indeed, Margot was a little astonished when she saw her daughter. Her husband had told her in a few words just how matters now lay between Ballister and Christine, and she was fully prepared with sympathy and counsels for the distracted, or angry, girl she expected to meet. So Christine’s beaming face, cheerful voice, and exceptional dress astonished her. “Lassie!” she exclaimed. “Whatna for hae you dressed yoursel’ sae early in the day?”

“I thought o’ going into the toun, Mither. I require some worsted for my knitting. I’m clean out o’ all sizes.”

“I was wanting you to go to the manse this morning. I am feared for the pain in my breast, dearie, and the powders the Domine gies me for it are gane. I dinna like to be without them.”

“I’ll go for them, Mither, this morning, as soon as I think the Domine is out o’ his study.”

“Then I’ll be contented. How are you feeling yoursel’, Christine?”

“Fine, Mither!”

“’Twas a grand ploy last night. That lad, Angus Ballister, danced with a’ and sundry, and sang, and ate wi’ the best, and the worst o’ us. I was hearing he was going awa’ for a year or mair.”

“Ay, to foreign parts. Rich young men think they arena educated unless they get a touch o’ France or Italy, and even America isna out o’ their way. You wad think a Scotch university wad be the complement o’ a Scotch gentleman!”

“Did he bid you good-by? Or is he coming here today?”

“He isna likely to ever come here again.”

“What for no? He’s been fain and glad to come up here. What’s changed him?”

“He isna changed. He has to go wi’ his uncle.”

“What did he say about marrying you? He ought to hae asked your feyther for ye?”

“For me?”

“Ay, for you.”

“Don’t say such words, Mither. There was no talk of marriage between us. What would Angus do with a girl like me for a wife?”

“You are gude enou’ for any man.”

“We are friends. We arena lovers. The lad has been friendly with the hale village. You mustna think wrang o’ him.”

“I do think vera wrang o’ him. He is just one kind o’ a scoundrel.”

“You hurt me, Mither. Angus is my friend. I’ll think nae wrang o’ him. If he was wrang, I was wrang, and you should hae told me I was wrang.”

“I was feared o’ hurting Neil’s chances wi’ him.”

“Sae we baith had a second motive.”

“Ay, few folk are moved by a single one.”

“Angus came, and he went, he liked me, and I liked him, but neither o’ us will fret o’er the parting. It had to be, or it wouldn’t hae been. Them above order such things. They sort affairs better than we could.”

“I don’t understand what you’re up to, but I think you are acting vera unwomanly.”

“Na, na, Mither! I’ll not play ‘maiden all forlorn’ for anyone. If Angus can live without me, there isna a woman i’ the world that can live without Angus as weel as Christine Ruleson can. Tuts! I hae you, Mither, and my dear feyther, and my six big brothers, and surely their love is enough for any soul through this life; forbye, there is the love beyond all, and higher than all, and truer than all – the love of the Father and the Son.”

“I see ye hae made up your mind to stand by Ballister. Vera weel! Do sae! As long as he keeps himsel’ in foreign pairts, he’ll ne’er fret me; but if he comes hame, he’ll hae to keep a few hundred miles atween us.”

“Nonsense! We’ll a’ be glad to see him hame.”

“Your way be it. Get your eating done wi’, and then awa’ to the manse, and get me thae powders. I’m restless and feared if I have none i’ the house.”

“I’ll be awa’ in ten minutes now. Ye ken the Domine doesna care for seeing folk till after ten o’clock. He says he hes ither company i’ the first hours o’ daybreak.”

“Like enou’, but he’ll be fain to hear about the doings last night, and he’ll be pleased concerning Faith getting a sweetheart. I doubt if she deserves the same.”

“Mither! Dinna say that. The puir lassie!”

“Puir lassie indeed! Her feyther left her forty pounds a year, till she married, and then the principal to do as she willed wi’. I dinna approve o’ women fretting and fearing anent naething.”

“But if they hae the fret and fear, what are they to do wi’ it, Mither?”

“Fight it. Fighting is better than fearing. Weel, tak’ care o’ yoursel’ and mind every word that you say.”

“I’m going by the cliffs on the sea road.”

“That will keep you langer.”

“Ay, but I’ll no require to mind my words. I’ll meet naebody on that road to talk wi’.”

“I would not say that much.”

A suspicion at once had entered Margot’s heart. “I wonder,” she mused, as she watched Christine out of sight – “I wonder if she is trysted wi’ Angus Ballister on the cliff road. Na, na, she would hae told me, whether or no, she would hae told me.”

The solitude of the sea, and of the lonely road, was good for Christine. She was not weeping, but she had a bitter aching sense of something lost. She thought of her love lying dead outside her heart’s shut door, and she could not help pitying both love and herself. “He was like sunshine on my life,” she sighed. “It is dark night now. All is over. Good-by forever, Angus! Oh, Love, Love!” she cried aloud to the sea. “Oh, you dear old troubler o’ the warld! I shall never feel young again. Weel, weel, Christine, I’ll not hae ye going to meet trouble, it isna worth the compliment. Angus may forget me, and find some ither lass to love – weel, then, if it be so, let it be so. I’ll find the right kind o’ strength for every hour o’ need, and the outcome is sure to be right. God is love. Surely that is a’ I need. I’ll just leave my heartache here, the sea can carry it awa’, and the winds blow it far off” – and she began forthwith a tender little song, that died down every few bars, but was always lifted again, until it swelled out clear and strong, as she came in sight of the small, white manse, standing bravely near the edge of a cliff rising sheerly seven hundred feet above the ocean. The little old, old kirk, with its lonely acres full of sailors’ graves, was close to it, and Christine saw that the door stood wide open, though it was yet early morning.

“It’ll be a wedding, a stranger wedding,” she thought. “Hame folk wouldna be sae thoughtless, as to get wed in the morning – na, na, it will be some stranger.”

These speculations were interrupted by the Domine’s calling her, and as soon as she heard his voice, she saw him standing at the open door. “Christine!” he cried. “Come in! Come in! I want you, lassie, very much. I was just wishing for you.”

“I am glad that I answered your wish, Sir. I would aye like to do that, if it be His will.”

“Come straight to my study, dear. You are a very godsend this morning.”

He went hurriedly into the house, and turned towards his study, and Christine followed him. And before she crossed the threshold of the room, she saw Angus and his Uncle Ballister, sitting at a table on which there were books and papers.

Angus rose to meet her at once. He did it as an involuntary act. He did not take a moment’s counsel or consideration, but sprang to his feet with the joyful cry of a delighted boy. And Christine’s face reflected the cry in a wonderful, wonderful smile. Then Angus was at her side, he clasped her hands, he called her by her name in a tone of love and music, he drew her closer to his side. And the elder man smiled and looked at the Domine, who remembered then the little ceremony he had forgotten.

So he took Christine by the hand, and led her to the stranger, and in that moment a great change came into the countenance and manner of the girl, while a peculiar light of satisfaction – almost of amusement – gleamed in her splendid eyes.

“Colonel Ballister,” said the Domine, “I present to you Miss Christine Ruleson, the friend of your nephew, the beloved of the whole village of Culraine.”

“I am happy to make Miss Ruleson’s acquaintance,” he replied and Christine said,

“It is a great pleasure to meet you, Sir. When you know Angus, you wish to know the man who made Angus well worth the love he wins.”

The Domine and Angus looked at the beautiful girl in utter amazement. She spoke perfect English, in the neat, precise, pleasant manner and intonation of the Aberdeen educated class. But something in Christine’s manner compelled their silence. She willed it, and they obeyed her will.

“Sit down at the table with us, Christine,” said the Domine. “We want your advice;” and she had the good manners to sit down, without affectations or apologies.

“Colonel, will you tell your own tale? There’s none can do it like you.”

“It is thus, and so, Miss Ruleson. Two nights ago as I sat thinking of Angus in Culraine, I remembered my own boyhood days in the village. I thought of the boats, and the sailors, and the happy hours out at sea with the nets, or the lines. I remembered how the sailors’ wives petted me, and as I grew older teased me, and sang to me. And I said to my soul, ‘We have been ungratefully neglectful, Soul, and we will go at once, and see if any of the old playfellows are still alive.’ So here I am, and though I find by the Domine’s kirk list that only three of my day are now in Culraine, I want to do some good thing for the place. The question is, what. Angus thinks, as my memories are all of playtime, I might buy land for a football field, or links for a golf club. What do you say to this idea, Miss Ruleson?”

“I can say naething in its favor, Sir. Fishers are hard-worked men; they do not require to play hard, and call it amusement. I have heard my father say that ball games quickly turn to gambling games. A game of any sort would leave all the women out. Their men are little at home, and it would be a heartache to them, if they took to spending that little in a ball field, or on the golf links.”

“Their wives might go with them, Christine,” said Angus.

“They would require to leave many home duties, if they did so. It would not be right – our women would not do it. Once I was at St. Andrews, and I wanted to go to the golf links with my father, but the good woman with whom we were visiting said: ‘James Ruleson, go to the links if so be you want to go, but you’ll no daur to tak’ this young lassie there. The language on the links is just awfu’. It isna fit for a decent lass to hear. No, Sir, golf links would be of no use to the women, and their value is very uncertain to men.’”

“Women’s presence would doubtless make men more careful in their language,” said Angus.

“Weel, Angus, it would be doing what my Mither ca’s ‘letting the price o’er-gang the profit.’”

“Miss Ruleson’s objections are good and valid, and we admit them,” said the Colonel; “perhaps she will now give us some idea we can work out” – and when he looked at her for response, he caught his breath at the beauty and sweetness of the face before him. “What are you thinking of?” he asked, almost with an air of humility, for the visible presence of goodness and beauty could hardly have affected him more. And Christine answered softly: “I was thinking of the little children.” And the three men felt ashamed, and were silent. “I was thinking of the little children,” she continued, “how they have neither schoolhouse, nor playhouse. They must go to the town, if they go to school; and there is the bad weather, and sickness, and busy mothers, and want of clothing and books, and shoes, and slates, and the like. Our boys and girls get at the Sunday School all the learning they have. The poor children. They have hard times in a fishing-village.”

“You have given us the best of advice, Miss Ruleson, and we will gladly follow it,” said the Colonel. “I am sure you are right. I will build a good schoolhouse in Culraine. I will begin it at once. It shall be well supplied with books and maps, and I will pay a good teacher.”