полная версия

полная версияGuy Deverell. Volume 2 of 2

"Yes, I do, I do; but it's all over, Jekyl, and I've come to bid you farewell, and on earth we'll never meet again," said Lady Jane, still weeping violently.

"Come, little Jennie, you shan't talk like a fool. I've heard you long enough; you must listen to me – I have more to say."

"Jekyl, Jekyl, I am sorry – oh! I'm sorry, for your sake, and for mine, I ever saw your face, and sorrier that I am to see you no more; but I've quite made up my mind – nothing shall change me – nothing – never. Good-bye, Jekyl. God forgive us. God bless you."

"Come, Jane, I say, don't talk that way. What do you mean?" said the Baronet, holding her hand fast in his, and with his other hand encircling her wrist. "If you really do want to make me ill, Jennie, you'll talk in that strain. I know, of course, I've been very much to blame. It was all my fault, I said – I say– everything; but now you will be free, Jennie. I wish I had been worthy of you; I wish I had. No, you must not go. Wait a moment. I say, Jennie, I wish to Heaven I had made you marry me when you might; but I'll not let you go now; by Heaven, I'll never run a risk of losing you again."

"No, Jekyl, no, I've made up my mind; it is all no use, I'll go. It is all over – quite over, for ever. Good-bye, Jekyl. God bless you. You'll be happier when we have parted – in a few days – a great deal happier; and as for me, I think I'm broken-hearted."

"By – , Jennie, you shan't go. I'll make you swear; you shall be my wife – by Heaven, you shall; we'll live and die together. You'll be happier than ever you were; we have years of happiness. I'll be whatever you like. I'll go to church – I'll be a Puseyite, or a Papist, or anything you like best. I'll – I'll – "

And with these words Sir Jekyl let go her hand suddenly, and with a groping motion in the air, dropped back on the pillows. Lady Jane cried wildly for help, and tried to raise him. The nurse was at her side, she knew not how. In ran Tomlinson, who, without waiting for directions, dashed water in his face. Sir Jekyl lay still, with waxen face, and a fixed deepening stare.

"Looks awful bad!" said Tomlinson, gazing down upon him.

"The wine – the claret!" cried the woman, as she propped him under the head.

"My God! what is it?" said Lady Jane, with white lips.

The woman made no answer, but rather shouldered her, as she herself held the decanter to his mouth; and they could hear the glass clinking on his teeth as her hand trembled, and the claret flowed over his still lips and down upon his throat.

"Lower his head," said the nurse; and she wiped his shining forehead with his handkerchief; and all three stared in his face, pale and stern.

"Call the doctor," at last exclaimed the nurse. "He's not right."

"Doctor's gone, I think," said Tomlinson, still gaping on his master.

"Send for him, man! I tell ye," cried the nurse, scarce taking her eyes from the Baronet.

Tomlinson disappeared.

"Is he better?" asked Lady Jane, with a gasp.

"He'll never be better; I'm 'feared he's gone, ma'am," answered the nurse, grimly, looking on his open mouth, and wiping away the claret from his chin.

"It can't be, my good Lord! it can't – quite well this minute – talking – why, it can't – it's only weakness, nurse! for God's sake, he's not – it is not – it can't be," almost screamed Lady Jane.

The nurse only nodded her head sternly, with her eyes still riveted on the face before her.

"He ought 'a bin let alone – the talkin's done it," said the woman in a savage undertone.

In fact she had her own notions about this handsome young person who had intruded herself into Sir Jekyl's sick-room. She knew Beatrix, and that this was not she, and she did not like or encourage the visitor, and was disposed to be sharp, rude, and high with her.

Lady Jane sat down, with her fingers to her temple, and the nurse thought she was on the point of fainting, and did not care.

Donica Gwynn entered, scared by a word and a look from Tomlinson as he passed her on the stair. She and the nurse, leaning over Sir Jekyl, whispered for a while, and the latter said —

"Quite easy – off like a child – all in a minute;" and she took Sir Jekyl's hand, the fingers of which were touching the table, and laid it gently beside him on the coverlet.

Donica Gwynn began to cry quietly, looking on the familiar face, thinking of presents of ribbons long ago, and school-boy days, and many small good-natured remembrances.

CHAPTER XXXVI

In the Chaise

Hearing steps approaching, Donica recollected herself, and said, locking the room door —

"Don't let them in for a minute."

"Who is she?" inquired the nurse, following Donica's glance.

"Lady Jane Lennox."

The woman looked at her with awe and a little involuntary courtesy, which Lady Jane did not see.

"A relation – a – a sort of a niece like of the poor master – a'most a daughter like, allays."

"Didn't know," whispered the woman, with another faint courtesy; "but she's better out o' this, don't you think, ma'am?"

"Drink a little wine, Miss Jennie, dear," said Donica, holding the glass to her lips. "Won't you, darling?"

She pushed it away gently, and got up, and looked at Sir Jekyl in silence.

"Come away, Miss Jennie, darling, come away, dear, there's people at the door. It's no place for you," said Donica, gently placing her hand under her arm, and drawing her toward the study door. "Come in here, for a minute, with old Donnie."

Lady Jane did go out unresisting, hurriedly, and weeping bitterly.

Old Donica glanced almost guiltily over her shoulder; the nurse was hastening to the outer door. "Say nothing of us," she whispered, and shut the study door.

"Come, Miss Jennie, darling; do as I tell you. They must not know."

They crossed the floor; at her touch the false door with its front of fraudulent books opened. They were now in a dark passage, lighted only by the reflection admitted through two or three narrow lights near the ceiling, concealed effectually on the outside.

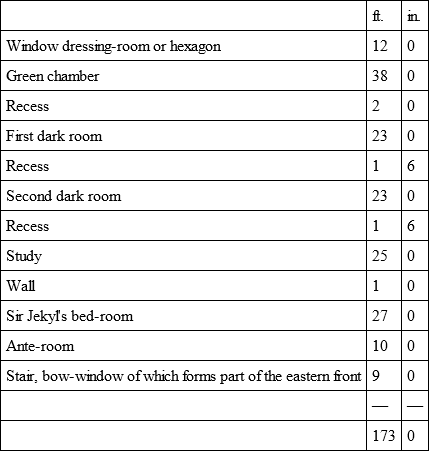

The reader will understand that I am here describing the architectural arrangements, which I myself have seen and examined. At the farther end of this room, which is about twenty-three feet long, is a niche, in which stands a sort of cupboard. This swings upon hinges, secretly contrived, and you enter another chamber of about the same length. This room is almost as ill-lighted as the first, and was then stored with dusty old furniture, piled along both sides, the lumber of fifty years ago. From the side of this room a door opens upon the gallery, which door has been locked for half a century, and I believe could hardly be opened from without.

At the other end of this dismal room is a recess, in one side of which is fixed an open press, with shelves in it; and this unsuspected press revolves on hinges also, shutting with a concealed bolt, and is, in fact, a door admitting to the green chamber.

It is about five years since I explored, under the guidance of the architect employed to remove this part of the building, this mysterious suite of rooms; and knowing, as I fancied, thoroughly the geography of the house, I found myself with a shock of incredulity thus suddenly in the green chamber, which I fancied still far distant. Looking to my diary, in which I that day entered the figures copied from the ground plan of the house, I find a little column which explains how the distance from front to rear, amounting to one hundred and seventy-three feet, is disposed of.

Measuring from the western front of the house, with which the front of the Window dressing-room stands upon a level, that of the green chamber receding about twelve feet: —

I never spoke to anyone who had made the same exploration who was not as much surprised as I at the unexpected solution of a problem which seemed to have proposed bringing the front and rear of this ancient house, by a "devilish cantrip slight," a hundred feet at least nearer to one another than stone mason and foot-rule had ordained.

The rearward march from the Window dressing-room to the foot of the back stair, which ascends by the eastern wall of the house, hardly spares you a step of the full distance of one hundred and seventy-three feet, and thus impresses you with an idea of complete separation, which is enhanced by the remote ascent and descent. When you enter Sir Jekyl's room, you quite forget that its great window looking rearward is in reality nineteen feet nearer the front than the general line of the rear; and when you stand in that moderately proportioned room, his study, which appears to have no door but that which opens into his bed-room, you could not believe without the evidence of these figures, that there intervened but two rooms of three-and-twenty feet in length each, between you and that green chamber, whose bow-window ranks with the front of the house.

Now Lady Jane sat in that hated room once more, a room henceforward loathed and feared in memory, as if it had been the abode of an evil spirit. Here, gradually it seemed, opened upon her the direful vista of the future; and as happens in tales of magic mirrors, when she looked into it her spirit sank and she fainted.

When she recovered consciousness – the window open – eau de cologne, sal volatile, and all the rest around her, with cloaks about her knees, and a shawl over her shoulders, she sat and gazed in dark apathy on the floor for a time. It was the first time in her life she had experienced the supernatural panic of death.

Where was Jekyl now? All irrevocable! Nothing in this moment's state changeable for ever, and ever, and ever!

This gigantic and inflexible terror the human brain can hardly apprehend or endure; and, oh! when it concerns one for whom you would have almost died yourself!

"Where is he? How can I reach him, even with the tip of my finger, to convey that one drop of water for which he moans now and now, and through all futurity?" Vain your wild entreaties. Can the dumb earth answer, or the empty air hear you? As the roar of the wild beast dies in solitude, as the foam beats in vain the blind cold precipice, so everywhere apathy receives your frantic adjuration – no sign, no answer.

Now, when Donica returned and roused Lady Jane from her panic, she passed into a frantic state – the wildest self-upbraidings; things that made old Gwynn beat her lean hand in despair on the cover of her Bible.

As soon as this frenzy a little subsided, Donica laid her hand firmly on the young lady's arm.

"Come, Lady Jane, you must stop that," she said, sternly. "What I hear matters nothing, but there's others that must not. The house full o' servants; think, my darling, and don't let yourself down. Come away with me to Wardlock – this is no place any longer for you – and let your maid follow. Come along, Miss Jennie; come, darling. Come by the glass door, there is no one there, and the chaise waiting outside. Come, miss, you must not lower yourself before the like o' them that's about the house."

It was an accident; but this appeal did touch her pride.

"Well, Donnie, I will. It matters little who now knows everything. Wait one moment – my face. Give me a towel."

And with feminine precaution she hastily bathed her eyes and face, looking into the glass, and adjusted her hair.

"A thick veil, Donnie."

Old Gwynn adjusted it, and Lady Jane gathered in its folds in her hand; and behind this mask, with old Donnie near her, she glided down-stairs without encountering anyone, and entered the carriage, and lay back in one of its corners, leaving to Gwynn, who followed, to give the driver his directions.

When they had driven about a mile, Lady Jane became strangely excited.

"I must see him again – I must see him. Stop it. I will. Stop it." She was tugging at the window, which was stiff. "Stop him, Gwynn. Stop him, woman, and turn back."

"Don't, Miss Jennie; don't, darling. Ye could not, miss. Ye would not face all them strangers, ma'am."

"Face them! What do you mean? Face them! How dare they? I despise them – I defy them! What is their staring and whispering to me? I'll go back. I'll return. I will see him again."

"Well, Miss Jennie, where's the good? He's cold by this time."

"I must see him again, Donnie – I must."

"You'll only see what will frighten you. You never saw a corpse, miss."

"Oh! Donnie, Donnie, Donnie, don't – you mustn't. Oh! Donnie, yes, he's gone, he is – he's gone, Donnie, and I've been his ruin. I – I – my wicked, wretched vanity. He's gone, lost for ever, and it's I who've done it all. It's I, Donnie. I've destroyed him."

It was well that they were driving in a lonely place, over a rough way, and at a noisy pace, for in sheer distraction Lady Jane screamed these wild words of unavailing remorse.

"Ah! my dear," expostulated Donica Gwynn. "You, indeed! Put that nonsense out of your head. I know all about him, poor master Jekyl; a wild poor fellow he was always. You, indeed! Ah! it's little you know."

Lady Jane was now crying bitterly into her handkerchief, held up to her face with both hands, and Donica was glad that her frantic fancy of returning had passed.

"Donnie," she sobbed at last – "Donnie, you must never leave me. Come with me everywhere."

"Better for you, ma'am, to stay with Lady Alice," replied old Donnie, with a slight shake of her head.

"I – I'd rather die. She always hated him, and hated me. I tell you, Gwynn, I'd swallow poison first," said Lady Jane, glaring and flushing fiercely.

"Odd ways, Miss Jane, but means kindly. We must a-bear with one another," said Gwynn.

"I hate her. She has brought this about, the dreadful old woman. Yes, she always hated me, and now she's happy, for she has ruined me – quite ruined – for nothing – all for nothing – the cruel, dreadful old woman. Oh, Gwynn, is it all true? My God! is it true, or am I mad?"

"Come, my lady, you must not take on so," said old Gwynn. "'Tisn't nothing, arter all, to talk so wild on. Doesn't matter here, shut up wi' me, where no one 'ears ye but old Gwynn, but ye must not talk at that gate before others, mind; there's no one talking o' ye yet – not a soul at Marlowe; no one knows nor guesses nothing, only you be ruled by me; you know right well they can't guess nothink; and you must not be a fool and put things in people's heads, d'ye see?"

Donica Gwynn spoke this peroration with a low, stern emphasis, holding the young lady's hand in hers, and looking rather grimly into her eyes.

This lecture of Donica's seemed to awaken her to reflection, and she looked for a while into her companion's face without speaking, then lowered her eyes and turned another way, and shook old Gwynn's hand, and pressed it, and held it still.

So they drove on for a good while in silence.

"Well, then, I don't care for one night – just one – and to-morrow I'll go, and you with me; we'll go to-morrow."

"But, my lady mistress, she won't like that, mayhap."

"Then I'll go alone, that's all; for another night I'll not stay under her roof; and I think if I were like myself nothing could bring me there even for an hour; but I am not. I am quite worn out."

Here was another long silence, and before it was broken they were among the hedgerows of Wardlock; and the once familiar landscape was around her, and the old piers by the roadside, and the florid iron gate, and the quaint and staid old manor-house rose before her like the scenery of a sick dream.

The journey was over, and in a few minutes more she was sitting in her temporary room, leaning on her hand, and still cloaked and bonneted, appearing to look out upon the antique garden, with its overgrown standard pear and cherry trees, but, in truth, seeing nothing but the sharp face that had gazed so awfully into space that day from the pillow in Sir Jekyl's bed-room.

CHAPTER XXXVII

Old Lady Alice talks with Guy

As Varbarriere, followed by Doocey and Guy, entered the hall, they saw Dives cross hurriedly to the library and shut the door. Varbarriere followed and knocked. Dives, very pallid, opened it, and looked hesitatingly in his face for a moment, and then said —

"Come in, come in, pray, and shut the door. You'll be – you'll be shocked, sir. He's gone – gone. Poor Jekyl! It's a terrible thing. He's gone, sir, quite suddenly."

His puffy, bilious hand was on Varbarriere's arm with a shifting pressure, and Varbarriere made no answer, but looked in his face sternly and earnestly.

"There's that poor girl, you know – my niece. And – and all so unexpected. It's awful, sir."

"I'm very much shocked, sir. I had not an idea there was any danger. I thought him looking very far from actual danger. I'm very much shocked."

"And – and things a good deal at sixes and sevens, I'm afraid," said Dives – "law business, you know."

"Perhaps it would be well to detain Mr. Pelter, who is, I believe, still here," suggested Varbarriere.

"Yes, certainly; thank you," answered Dives, eagerly ringing the bell.

"And I've a chaise at the door," said Varbarriere, appropriating Guy's vehicle. "A melancholy parting, sir; but in circumstances so sad, the only kindness we can show is to withdraw the restraint of our presence, and to respect the sanctity of affliction."

With which little speech, in the artificial style which he had contracted in France, he made his solemn bow, and, for the last time for a good while, shook the Rev. Dives, now Sir Dives Marlowe, by the hand.

When our friend the butler entered, it was a comfort to see one countenance on which was no trace of flurry. Nil admirari– his manner was a philosophy, and the convivial undertaker had acquired a grave suavity of demeanour and countenance, which answered all occasions – imperturbable during the comic stories of an after-dinner sederunt – imperturbable now on hearing the other sort of story, known already, which the Rev. Dives Marlowe recounted, and offered, with a respectful inclination, his deferential but very short condolences.

Varbarriere in the meanwhile looked through the hall vestibule and from the steps, in vain, for his nephew! He encountered Jacques, however, but he had not seen Guy, which when Varbarriere, who was in one of his deep-seated fusses, heard, he made a few sotto voce ejaculations.

"Tell that fellow – he's in the stable-yard, I dare say – who drove Mr. Guy from Slowton, to bring his chaise round this moment; we shall return. If his horses want rest, they can have it in the town, Marlowe, close by; I shall send a carriage up for you; and you follow, with all our things, immediately for Slowton."

So Jacques departed, and Varbarriere did not care to go up-stairs to his room. He did not like meeting people; he did not like the chance of hearing Beatrix cry again; he wished to be away, and his temper was savage. He could have struck his nephew over the head with his cane for detaining him.

But Guy had been summoned elsewhere. As he walked listlessly before the house, a sudden knocking from the great window of Lady Mary's boudoir caused him to raise his eyes, and he saw the grim apparition of old Lady Alice beckoning to him. As he raised his hat, she nodded at him, pale, scowling like an evil genius, and beckoned him fiercely up with her crooked fingers.

Another bow, and he entered the house, ascended the great stair, and knocked at the door of the boudoir. Old Lady Alice's thin hand opened it. She nodded in the same inauspicious way, pointed to a seat, and shut the door before she spoke.

Then, he still standing, she took his hand, and said, in tones unexpectedly soft and fond —

"Well, dear, how have you been? It seems a long time, although it's really nothing. Quite well, I hope?"

Guy answered, and inquired according to usage; and the old lady said —

"Don't ask for me; never ask. I'm never well – always the same, dear, and I hate to think of myself. You've heard the dreadful intelligence – the frightful event. What will become of my poor niece? Everything in distraction. But Heaven's will be done. I shan't last long if this sort of thing is to continue – quite impossible. There – don't speak to me for a moment. I wanted to tell you, you must come to me; I have a great deal to say," she resumed, having smelt a little at her vinaigrette; "but not just now. I'm not equal to all this. You know how I've been tried and shattered."

Guy was too well accustomed to be more than politely alarmed by those preparations for swooning which Lady Alice occasionally saw fit to make; and in a little while she resumed —

"Sir Jekyl has been taken from us – he's gone – awfully suddenly. I wish he had had a little time for preparation. Ho, dear! poor Jekyl! Awful! But we all bow to the will of Providence. I fear there has been some dreadful mismanagement. I always said and knew that Pratt was a quack – positive infatuation. But there's no good in looking to secondary causes, Won't you sit down?"

Guy preferred standing. The hysterical ramblings of this selfish old woman did not weary or disgust him. Quite the contrary; he would have prolonged them. Was she not related to Beatrix, and did not this kindred soften, beautify, glorify that shrivelled relic of another generation, and make him listen to her in a second-hand fascination?

"You're to come to me – d'ye see? – but not immediately. There's a – there's some one there at present, and I possibly shan't be at home. I must remain with poor dear Beatrix a little. She'll probably go to Dartbroke, you know; yes, that would not be a bad plan, and I of course must consider her, poor thing. When you grow a little older you'll find you must often sacrifice yourself, my dear. I've served a long apprenticeship to that kind of thing. You must come to Wardlock, to my house; I have a great deal to say and tell you, and you can spend a week or so there very pleasantly. There are some pictures and books, and some walks, and everybody looks at the monuments in the church. There are two of them – the Chief Justice of Chester and Hugo de Redcliffe – in the "Gentleman's Magazine." I'll show it to you when you come, and you can have the carriage, provided you don't tire the horses; but you must come. I'm your kinswoman – I'm your relation – I've found it all out – very near – your poor dear father."

Here Lady Alice dried her eyes.

"Well, it's time enough. You see how shattered I am, and so pray don't urge me to talk any more just now. I'll write to you, perhaps, if I find myself able; and you write to me, mind, directly, and address to Wardlock Manor, Wardlock. Write it in your pocket-book or you'll forget it, and put "to be forwarded" on it. Old Donica will see to it. She's very careful, I think; and you promise you'll come?"

Guy did promise; so she said —

"Well, dear, till we meet, good-bye; there, God bless you, dear."

And she drew his hand toward her, and he felt the loose soft leather of her old cheek on his as she kissed him, and her dark old eyes looked for a moment in his, and then she dismissed him with —

"There, dear, I can't talk any more at present; there, farewell. God bless you."

Down through that changed, mysterious house, through which people now trod softly, and looked demure, and spoke little on stair or lobby, and that in whispers, went Guy Deverell, and glanced upward, involuntarily, as he descended, hoping that he might see the beloved shadow of Beatrix on the wall, or even the hem of her garment; but all was silent and empty, and in a few seconds more he was again in the chaise, sitting by old Varbarriere, who was taciturn and ill-tempered all the way to Slowton.

By that evening all the visitors but the Rev. Dives Marlowe and old Lady Alice, who remained with Beatrix, had taken flight. Even Pelter, after a brief consultation with Dives, had fled Londonwards, and the shadow and silence of the chamber of death stole out under the door and pervaded all the mansion.

That evening Lady Alice recovered sufficient strength to write a note to Lady Jane, telling her that in consequence of the death of Sir Jekyl, it became her duty to remain with her niece for the present at Marlowe. It superadded many religious reflections thereupon; and offering to her visitor at Wardlock the use of that asylum, and the society and attendance of Donica Gwynn, it concluded with many wholesome wishes for the spiritual improvement of Lady Jane Lennox.