полная версия

полная версияWitch, Warlock, and Magician

‘iv. Item.– A horse of Duncan Alexander, in Newburcht, being bewitched, the said Helen translated the sickness from the horse to a young cow of the said Duncan; which cow died, and was cast into the burn of the Newburcht, for no man would eat her.

‘v. Item.– The said Helen made a compact with certain laxis fishers of the Newburcht, at the kirk of Foverne, in Mallie Skryne’s house, and promised to cause them to fish well, and to that effect received of them a piece of salmon to handle at her pleasure for accomplishing the matter. Upon the morrow she came to the Newburcht, to the house of John Ferguson, a laxis fisher, and delivered unto him in a closet four cuts of salmon with a penny; after that she called him out of his own house, from the company that was there drinking with him, and bade him put the same in the horn of his coble, and he should have a dozen of fish at the first shot; which came to pass.

‘vi. Item.– The said Helen, by witchcraft, enticed Gilbert Davidson, son to William Davidson, in Lytoune of Meanye, to love and marry Margaret Strauthachin (in the Hill of Balgrescho) directly against the will of his parents, to the utter wreck of the said Gilbert.

‘vii. Item.– At the desire of the said Margaret Strauthachin, by witchcraft, the said Helen made Catherine Fetchil, wife to William Davidson, furious, because she was against the marriage, and took the strength of her left side and arm from her; in the which fury and feebleness the said Catherine died.

‘viii. Item.– The said Helen, at the desire of the foresaid Margaret Strauthachin, bewitched William Hill, dwelling for the time at the Hill of Balgrescho, through which he died in a fury [i. e., a fit of delirium].

‘ix. Moreover, at the desire foresaid, the said Helen by witchcraft slew an ox belonging to the said William; for while Patrick Hill, son to the said William, and herd to his father, called in the cattle to the fold, at twelve o’clock, the said Helen was sitting in the yeite, and immediately after the outcoming of the cattle out of the fold, the best ox of the whole herd instantly died.

‘x. Item.– The said Helen counselled Christane Henderson, vulgarly called mickle Christane, to put one hand to the crown of her head, and the other to the sole of her foot, and so surrender whatever was between her hands, and she should want nothing that she could wish or desire.

‘xi. Item.– The said Christane Henderson, being henwife in Foverne, the young fowls died thick; for remedy whereof, the said Helen bade the said Christane take all the chickens or young fowls, and draw them through the link of the crook, and take the hindmost, and slay with a fiery stick, which thing being practised, none died thereafter that year.

‘xii. Item.– When the said Helen was dwelling in the Moorhill of Foverne, there came a hare betimes, and sucked a milch cow pertaining to William Findlay, at the Mill of the Newburght, whose house was directly afornent the said Helen’s house, on the other side of the Burn of Foverne, wherethrough the cow pined away, and gave blood instead of milk. This mischief was by all men attributed to the said Helen, and she herself cannot deny but she was commonly evil spoken of for it, and affirmed, after her apprehension at Foverne, that she was so slandered.

‘xiii. Item.– When Alexander Hardy, in Aikinshill, departed this life, it grieved and troubled his conscience very mickle, that he had been a defender of the said Helen, and especially that he, accompanied with Malcolm Forbes, travailed, against their conscience, with sundry of the assessors when she suffered an assize, and especially with the Chancellor of the Assize, in her favour, he knowing evidently her to be guilty of death.

‘xiv. Item.– The said Helen being a domestic in the said Alexander Hardy’s house, disagreed with one of the said Alexander’s servants, named Andrew Skene, and intending to bewitch the said servant, the evil fell upon Alexander, and he died thereof.

‘xv. Item.– When Robert Goudyne, now in Balgrescho, was dwelling in Blairtoun of Balheluies, a discord fell out betwixt Elizabeth Dempster, nurse to the said Robert for the time, and Christane Henderson, one of the said Helen’s familiars, as her own confession aforesaid purports, and the country well knows. Upon the which discord, the said Christane threatened the said Elizabeth with an evil turn, and to the performing thereof, brought the said Helen Frazer to the said Robert’s house, and caused her to repair oft thereto. After what time, immediately both the said Elizabeth and the infant to whom she gave suck, by the devilry of the said Helen, fell into a consuming sickness, whereof both died. And also Elspet Cheyne, spouse to the said Robert, fell into the selfsame sickness, and was heavily diseased thereby for the space of two years before the recovery of his health.

‘xvi. Item.– By witchcraft the said Helen abstracted and withdrew the love and affection of Andrew Tilliduff of Rainstoune, from his spouse Isabel Cheyne, to Margaret Neilson, and so mightily bewitched him, that he could never be reconciled with his wife, or remove his affection from the said harlot; and when the said Margaret was begotten with child, the said Helen conveyed her away to Cromar to obscure the fact.

‘xvii. Item.– Wherever the said Helen is known, or has repaired there many years bygone, she has been, and is reported by all, of whatsoever estate or sex, to be a common and abominable witch, and to have learned the same of the late Maly Skene, spouse to the late Cowper Watson, with whom, during her lifetime, the said Helen had continual society. The said Maly was bruited to be a rank witch, and her said husband suffered death for the same crime.

‘xviii. Item.– When Robert Merchant, in the Newbrucht, had contracted marriage, and holden house for the space of two years with the late Christane White, it happened to him to pass to the Moorhill of Foverne, to sow corn to the late Isabel Bruce, the relict of the late Alexander Frazer, the said Helen Frazer being familiar and actually resident in the house of the said Isabel, she was there at his coming: from the which time forth the said Robert found his affection violently and extraordinarily drawn away from the said Christane to the said Isabel, a great love being betwixt him and the said Christane always theretofore, and no break of love, or discord, falling out or intervening upon either of their parts, which thing the country supposed and spake to be brought about by the unlawful travails of the said Helen.

‘[Signed] Thomas Tilideff,

‘Minister, at Fovern, with my hand.

‘Item.– A common witch by open voice and common fame.’

I have given this ‘dittay’ in full, from a conviction that no summary would do justice to its terrible simplicity. Upon the evidence which it afforded, Helen Frazer was brought before the Court of Justiciary, in Aberdeen, on April 21, 1597, and found guilty in ‘fourteen points of witchcraft and sorcery.’

The burning of witches went merrily on, so that the authorities of Aberdeen were compelled to get in an adequate stock of fuel. We note in the municipal accounts, under the date of March 10, that there was ‘bocht be the comptar, and laid in be him in the seller in the Chappell of the Castel hill, ane chalder of coillis, price thairof, with the bieing and metting of the same, xvilib. iiiish.’ As is usually the case, the frequency of these sad exhibitions whetted at first the public appetite for them; it grew by what it fed on. One of the items of expense in the execution of a witch named Margaret Clerk, is for carrying of ‘four sparris, to withstand the press of the pepill, quhairof thair was twa broken, viiis. viiid.’

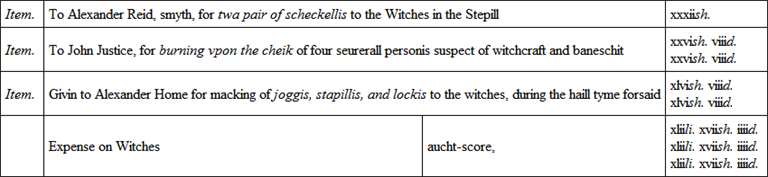

Among the victims committed to the flames in 1596-97, we read the names of ‘Katherine Fergus and [Sculdr], Issobel Richie, Margaret Og, Helene Rodger, Elspet Hendersoun, Katherine Gerard, Christin Reid, Jenet Grant, Helene Frasser, Katherine Ferrers, Helene Gray, Agnes Vobster, Jonat Douglas, Agnes Smelie, Katherine Alshensur, and ane other witche, callit …’ – seventeen in all. That during their imprisonment they were treated with barbarous rigour, may be inferred from the following entries:

On September 21, 1597, the Provost, Baillies and Council of Aberdeen considered the faithfulness shown by William Dun, the Dean of Guild, in the discharge of his duty, ‘and, besides this, his extraordinarily taking pains in the burning of the great number of the witches burnt this year, and on the four pirates, and bigging of the port on the Brig of Dee, repairing of the Grey Friars kirk and steeple thereof, and thereby has been abstracted from his trade of merchandise, continually since he was elected in the said office. Therefore, in recompense of his extraordinary pains, and in satisfaction thereof (not to induce any preparative to Deans of Guild to crave a recompense hereafter), but to encourage others to travail as diligently in the discharge of their office, granted and assigned to him the sum of forty-seven pounds three shillings and fourpence, owing by him of the rest of his compt of the unlawis [fines] of the persons convict for slaying of black fish, and discharged him thereof by their presents for ever.’

At length a wholesome reaction took place; the public grew weary of the number of executions, and, encouraged by this change of sentiment, persons accused of witchcraft boldly rebutted the charge, and laid complaints against their accusers for defamation of character. In official circles, it is true, a belief in the alleged crime lingered long. As late as 1669, ‘the new and old Councils taking into their serious consideration that many malefices were committed and done by several persons in this town, who are mala fama, and suspected guilty of witchcraft upon many of the inhabitants of this town, several ways, and that it will be necessary for suppressing the like in time coming, and for punishing the said persons who shall be found guilty; therefore they do unanimously conclude and ordain that any such person, who is suspect of the like malefices, may be seized upon, and put in prisoun, and that a Commission be sent for, for putting of them to trial, that condign justice may be executed upon them, as the nature of the offence does merit.’ No more victims, however, were sacrificed; nor does it appear that any accusation of witchcraft was preferred.

According to Sir Walter Scott, a woman was burnt as a witch in Scotland as late as 1722, by Captain Ross, sheriff-depute of Sutherland; but this was, happily, an exceptional barbarity, and for some years previously the pastime of witch-burning had practically been extinct. It is a curious fact that educated Scotchmen, as I have already noted, retained their superstition long after the common people had abandoned it. In 1730, Professor Forbes, of Glasgow, published his ‘Institutes of the Law of Scotland,’ in which he spoke of witchcraft as ‘that black art whereby strange and wonderful things are wrought by power derived from the devil,’ and added: ‘Nothing seems plainer to me than that there may be and have been witches, and that perhaps such are now actually existing.’ Six years later, the Seceders from the Church of Scotland, who professed to be the true representatives of its teaching, strongly condemned the repeal of the laws against witchcraft, as ‘contrary,’ they said, ‘to the express letter of the law of God.’ But they were hopelessly behind the time; public opinion, as the result of increased intelligence, had numbered witchcraft among the superstitions of the past, and we may confidently predict that its revival is impossible.

CHAPTER V

THE LITERATURE OF WITCHCRAFT

It should teach us humility when we find a belief in witchcraft and demonology entertained not only by the uneducated and unintelligent classes, but also by the men of light and leading, the scholar, the philosopher, the legislator, who might have been expected to have risen above so degrading a superstition. It would be manifestly unfair to direct our reproaches at the credulous prejudices of the multitude when Francis Bacon, the great apostle of the experimental philosophy, accepts the crude teaching of his royal master’s ‘Demonologie,’ and actually discusses the ingredients of the celebrated ‘witches’ ointment,’ opining that they should all be of a soporiferous character, such as henbane, hemlock, moonshade, mandrake, opium, tobacco, and saffron. The weakness of Sir Matthew Hale, to which reference has been made in a previous chapter, we cannot very strongly condemn, when we know that it was shared by Sir Thomas Browne, who had so keen an eye for the errors of the common people, and whose fine and liberal genius throws so genial a light over the pages of the ‘Religio Medici.’ In his ‘History of the World,’ that consummate statesman, poet, and scholar, Sir Walter Raleigh, gravely supports the vulgar opinions which nowadays every Board School alumnus would reject with disdain. Even the philosopher of Malmesbury, the sagacious author of ‘The Leviathan,’ Thomas Hobbes, was infected by the prevalent delusion. Dr. Cudworth, to whom we owe the acute reasoning of the treatises on ‘Moral Good and Evil,’ and ‘The True Intellectual System of the Universe,’ firmly holds that the guilt of a reputed witch might be determined by her inability or unwillingness to repeat the Lord’s Prayer. Strangest of it all is it to find the pure and lofty spirit of Henry More, the founder of the school of English Platonists, yielding to the general superstition. With large additions of his own, he republished the Rev. Joseph Glanvill’s notorious work, ‘Sadducismus Triumphatus’ – a pitiful example of the extent to which a fine intellect may be led astray, though Mr. Lecky thinks it the most powerful defence of witchcraft ever published. And the sober and fair-minded Robert Boyle, in the midst of his scientific researches, found time to listen, with breathless interest, to ‘stories of witches at Oxford, and devils at Muston.’

Among the Continental authorities on witchcraft, the chief of those who may be called its advocates are, Martin Antonio Delrio (1551-1608), who published, in the closing years of the sixteenth century, his ‘Disquisitionarum Magicarum Libri Sex,’ a formidable folio, brimful of credulity and ingenuity, which was translated into French by Duchesne in 1611, and has been industriously pilfered from by numerous later writers. Delrio has no pretensions to critical judgment; he swallows the most monstrous inventions with astounding facility.

Reference must also be made to the writings of Remigius, included in Pez’ ‘Thesaurus Anecdotorum Novissimus,’ and to the great work by H. Institor and J. Sprenger, ‘Malleus Maleficarum,’ as well as to Basin, Molitor (‘Dialogus de Lamiis’), and other authors, to be found in the 1582 edition of ‘Mallei quorundam Maleficarum,’ published at Frankfort.

On the same side we find the great philosophical lawyer and historian John Bodin (1530-1596), the author of the ‘Republicæ,’ and the ‘Methodus ad facilem Historiarum Cognitionem.’ In his ‘Demonomanie des Sorcius’ he recommends the burning of witches and wizards with an earnestness which should have gone far to compensate for his heterodoxy on other points of belief and practice. He informs us that from his thirty-seventh year he had been attended by a familiar spirit or demon, which touched his ear whenever he was about to do anything of which his conscience disapproved; and he quotes passages from the Psalms, Job, and Isaiah, to prove that spirits indicate their presence to men by touching and even pulling their ears, and not only by vocal utterances.

Also, Thomas Erastus (1524-1583), physician and controversialist, who took so busy a part in the theological dissensions of his time. In 1577 he published a tract (‘De Lamiis’) on the lawfulness of putting witches to death. It is strange that he should have been mastered by the gross imposture of witchcraft, when he could expose with trenchant force the pretensions of alchemists, astrologers, and Rosicrucians.

Happily, the cause of humanity, truth and tolerance was not without its eager and capable defenders. The earliest I take to have been the Dutch physician, Wierus, who, in his treatise ‘De Præstigiis,’ published at Basel in 1564, vigorously attacked the cruel prejudice that had doomed so many unhappy creatures to the stake. He did not, however, deny the existence of witchcraft, but demanded mercy for those who practised it on the ground that they were the devil’s victims, not his servants. That he should have been wholly devoid of credulity would have been more than one could rightly have expected of a disciple of Cornelius Agrippa.

A stronger and much more successful assailant appeared in Reginald Scot (died 1599), a younger son of Sir John Scot, of Scot’s Hall, near Smeeth, who published his celebrated ‘Discoverie of Witchcraft’ in 1584 – a book which, in any age, would have been remarkable for its sweet humanity, breadth of view, and moderation of tone, as well as for its literary excellencies. One wonders where this quiet Kentish gentleman, whose chief occupations appear to have been gardening and planting, accumulated his erudition, and how, in the face of the superstitions of his contemporaries, he arrived at such large and liberal conclusions. The scope of his great work is indicated in its lengthy title: ‘The Discoverie of Witchcraft, wherein the lewd dealing of Witches and Witchmongers is notablie detected, the knaverie of conjurers, the impietie of enchanters, the follie of soothsaiers, the impudent falsehood of couseners, the infidelitie of atheists, the pestilent practices of Pythonists, the curiositie of figure-casters [horoscope-makers], the vanitie of dreamers, the beggarlie art of Alcumystrie, the abhomination of idolatrie, the horrible art of poisoning, the vertue and power of naturall magike, and all the conveyances of Legierdemain and juggling are deciphered: and many other things opened, which have long lain hidden, howbeit verie necessarie to be knowne. Heerevnto is added a treatise upon the Nature and Substance of Spirits and Devils, etc.: all latelie written by Reginald Scot, Esquire. 1 John iv. 1: “Believe not everie spirit, but trie the spirits, whether they are of God; for many false prophets are gone out into the world.”’

From a book so well known – a new edition has recently appeared – it is needless to make extracts; but I transcribe a brief passage in illustration of the vivacity and manliness of the writer:

‘I, therefore (at this time), do only desire you to consider of my report concerning the evidence that is commonly brought before you against them. See first whether the evidence be not frivolous, and whether the proofs brought against them be not incredible, consisting of guesses, presumptions, and impossibilities contrary to reason, Scripture, and nature. See also what persons complain upon them, whether they be not of the basest, the unwisest, and the most faithless kind of people. Also, may it please you, to weigh what accusations and crimes they lay to their charge, namely: She was at my house of late, she would have had a pot of milk, she departed in a chafe because she had it not, she railed, she cursed, she mumbled and whispered; and, finally, she said she would be even with me: and soon after my child, my cow, my sow, or my pullet died, or was strangely taken. Nay (if it please your Worship), I have further proof: I was with a wise woman, and she told me I had an ill neighbour, and that she would come to my house ere it was long, and so did she; and that she had a mark about her waist, and so had she: God forgive me, my stomach hath gone against her a great while. Her mother before her was counted a witch; she hath been beaten and scratched by the face till blood was drawn upon her, because she hath been suspected, and afterwards some of those persons were said to amend. These are the certainties that I hear in their evidences.

‘Note, also, how easily they may be brought to confess that which they never did, nor lieth in the power of man to do; and then see whether I have cause to write as I do. Further, if you shall see that infidelity, popery, and many other manifest heresies be backed and shouldered, and their professors animated and heartened, by yielding to creatures such infinite power as is wrested out of God’s hand, and attributed to witches: finally, if you shall perceive that I have faithfully and truly delivered and set down the condition and state of the witch, and also of the witchmonger, and have confuted by reason and law, and by the Word of God itself, all mine adversary’s objections and arguments; then let me have your countenance against them that maliciously oppose themselves against me.

‘My greatest adversaries are young ignorance and old custom. For what folly soever tract of time hath fostered, it is so superstitiously pursued of some, as though no error could be acquainted with custom. But if the law of nations would join with such custom, to the maintenance of ignorance and to the suppressing of knowledge, the civilest country in the world would soon become barbarous. For as knowledge and time discovereth errors, so doth superstition and ignorance in time breed them.’

In another fine passage Scot says:

‘God that knoweth my heart is witness, and you that read my book shall see, that my drift and purpose in this enterprise tendeth only to these respects. First, that the glory and power of God be not so abridged and abused, as to be thrust into the hand or lip of a lewd old woman, whereby the work of the Creator should be attributed to the power of a creature. Secondly, that the religion of the Gospel may be seen to stand without such peevish trumpery. Thirdly, that lawful favour and Christian compassion be rather used towards these poor souls than rigour and extremity. Because they which are commonly accused of witchcraft are the least sufficient of all other persons to speak for themselves, as having the most base and simple education of all others; the extremity of their age giving them leave to dote, their poverty to beg, their wrongs to chide and threaten (as being void of any other way of revenge), their humour melancholical to be full of imaginations, from whence chiefly proceedeth the vanity of their confessions, as that they can transform themselves and others into apes, owls, asses, dogs, cats, etc.; that they can fly in the air, kill children with charms, hinder the coming of butter, etc.

‘And for so much as the mighty help themselves together, and the poor widow’s cry, though it reach to heaven, is scarce heard here upon earth, I thought good (according to my poor ability) to make intercession, that some part of common rigour and some points of hasty judgment may be advised upon. For the world is now at that stay (as Brentius, in a most godly sermon, in these words affirmeth), that even, as when the heathen persecuted the Christians, if any were accused to believe in Christ, the common people cried Ad leonem; so now, of any woman, be she never so honest, be she accused of witchcraft, they cry Ad ignem.’

Scot’s attack upon the credulity of his contemporaries, strenuous and capable as it was, did not bear much fruit at the time; while it exposed him to charges of Atheism and Sadduceeism from several small critics, who were supported by the authority of James I., and, at a later date, of Dr. Meric Casaubon. He found a fellow-labourer, however, in his work of humanity, in the Rev. George Gifford, of Maldon, Essex, who in 1593 published ‘A Dialogue concerning Witches and Witchcraft,’ in which ‘is layed open how craftily the Divell deceiveth not only the Witches but Many other, and so leadeth them awaie into Manie Great Errours.’ It will be seen from the title that the writer does not adopt the uncompromising line of Reginald Scot, but inclines rather to the standpoint of Wierus. There is, however, a good deal of ability in his treatment of the question; and some account of the ‘Dialogue’ reprinted by the Percy Society in 1842, should be interesting, I think, to the reader.

The interlocutors are named Samuel, Daniel, Samuel’s wife, M. B., a schoolmaster, and the goodwife R.