полная версия

полная версияThe Great God Gold

What was written upon the paper was as follows:

The Professor begged leave to take it with him to London, whereupon the assistant-librarian replied: “It seems very much as though our friend the stranger is applying some numerical cipher to that fragment of Deuteronomy, does it not? Of course, Professor, you may have it – and welcome. I confess I cannot make head or tail of it.”

“Nor I either,” laughed Griffin, blinking through his spectacles. “Yet it interests me, and I thank you very much for it. Apparently this foreigner believes that he has made some discovery. Ah!” he added, “how many cranks there are among Hebrew scholars – more especially the cabalists!”

And in pretence of ignorance of the true meaning of that curious arrangement of figures, the Professor placed the scrap of paper in his breast-pocket, and returned to the Randolph Hotel, where he had tea, afterwards sitting for a long time in the writing-room with the stranger’s discarded calculation spread before him.

In the left-hand corner of the piece of paper was something which puzzled him extremely. In a neat hand were written the figures, 255.19.7. And while awaiting his train, he lit his big briar pipe, and seating himself before the fire, tried to think out what they could mean.

But though he pondered for over an hour he failed to discern their object. They were evidently the stranger’s signature.

He applied the Hebrew equivalents to them, and they were as follows: “Bêth. He. He, A-leph-Teth. Za-yin.” But they conveyed to him absolutely nothing.

Seated alone in the corner of the first-class carriage, he again took out the scrap of paper, and held it before him. That there was a cipher deciphered into the words “of the Temple that,” was apparent.

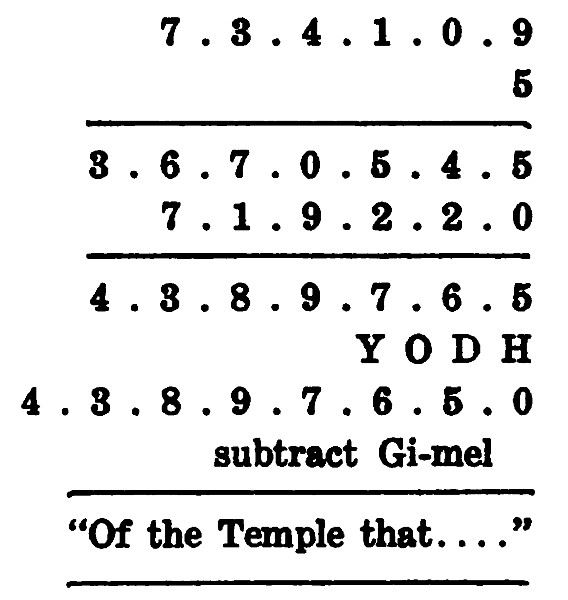

He started with the ordinary numerical values of the Hebrew alphabet. They were 7.3.4.1.0.9. which meant: Za-yin, Gi-mel, Da-leth, A-leph, the zero, and Teth. These were multiplied by He, which meant 5. Then 719220, meaning certain other letters, were added and multiplied by yodh, or ten. From each number of the total 3, or Gi-mel, was subtracted, and the English translation of the figures that remained was: “of the Temple that – ”

To such a man, versed in all the cabalistic ciphers of the ancients, the truth was plain. Extremely involved and ingenious it was, without a doubt, but by careful study of this he would, he saw, be able to find the key being used by the aged man who had in such an uncanny way signed himself “255.19.7.”

He replaced it carefully in his pocket, and lighting his pipe, set back in the carriage to reflect.

Ah! if he could only come across that will-o’-the-wisp who was engaged in the search after the truth. Probably he possessed the context of the burnt document, and could supply the missing portion. But if so, how had it fallen into his hands?

The affair was a problem which daily became more interesting and more extraordinary.

At Westbourne Park Station, when the collector came for his ticket, he fumbled for it in his pocket, but was unable for some time to find it. Then at Paddington he took a taxi-cab home, arriving in time for a late dinner.

Gwen bright and cheerful, sat at the head of the table as was her habit, inquisitive as to her father’s movements and discoveries.

But to her carefully guarded inquiries he remained mute. He had been down to the Bodleian, he said, but that was all. The old man longed to get back to the restful silence of his own study to examine the scrap of paper left by the stranger, and from it to determine the exact key to that very ingenious numerical cipher.

The man who was in search of the same secret as himself was a weird person, to say the least. Both in London and in Oxford, he had come across the aged man’s trail. That he was unknown in England as a scholar was apparent, and that he was a deeply read man and student of Hebrew was equally plain.

He was not a Jew. Both the Library assistants at the British Museum and at the Bodleian had agreed upon that point.

They had declared that he was from the north of Europe. Was he a Dane from Copenhagen, like the dead man who had preferred to be known as Jules Blanc?

Arminger Griffin ate his dinner in impatience carefully avoiding the questions his pretty daughter put to him. Then he ascended to the study, having bidden her good-night. She had received no news of Frank, it seemed. For what reason had the young man so suddenly left for Copenhagen? The question caused him constant apprehension. Could he have discovered any clue to the existence of the context of the document?

More than once during the day he had been half tempted to go himself to Denmark, but the discovery of the aged stranger’s arithmetical calculations induced him to remain in London and watch.

Having switched on the light he crossed the room, and seating himself at the table felt in his pocket for the scribbled calculation. He failed to find it. He was horrified. It had gone!

He must have pulled it from his pocket at Westbourne Park while searching for his ticket. His loss was, indeed, a serious one. In frantic haste he searched all his other pockets, but in vain. The scraps of crumpled paper which contained the key to a portion of the cipher upon which the stranger was working was gone!

He sank into his armchair in despair.

Before his vision rose those mystical figures 255.19.7. written in fire. What was the hidden meaning therein contained?

One line of the sum he recollected: “7.3.4.1.0.9.” multiplied by 5. Mental calculation resulted in the answer of 3670646. There was a sum to add to it. But alas! he could not remember the figures of it.

Therefore the clue, so unexpectedly obtained, was lost.

So he sat alone, his head buried in his hands in deepest despair.

Gwen crept in in silence, but seeing her father’s attitude, crept out again without disturbing him, and read in the drawing-room alone, until it was time to return to her room.

“Shall I ever solve the mystery?” cried the Professor aloud to himself as he paced the room presently. “Misfortune has befallen me! With that fragment deciphered I could by careful study have learned the key and then read what that mysterious searcher has undoubtedly read. Ah! if I could only meet him. Then I would follow and watch his movements. But alas! I am always too late – too late!”

As he sank again into a chair, plunged in the wildest despair, the dark figure of a tall, thick-set, military-looking man of about forty, in a long dark overcoat, passed and repassed the house in the rainy night.

For some time, he had been waiting at Notting Hill Gate Station, almost opposite the end of Pembridge Gardens, glancing at the clock now and then, as though impatiently watching for someone. Then, at last, as if full of determination he had crossed the Bayswater Road, and strolled slowly past Professor Griffin’s house, eyeing its lighted windows with considerable curiosity as he went by.

He continued his walk as far as the end of the road which led into Pembridge Square, and there halted for shelter for a full five minutes beneath the portico of a house. Then he retraced his steps, re-passing the house which had aroused so much interest within him, until he came to the station where he again stood in patience.

The watcher was an active, rather good-looking man, though the reason of his presence there was not at all apparent. To pass the time he bought an evening paper, and stood in the corner reading it, yet in such a position that he could watch everybody who entered or left the Underground Railway Station. There was a slight foreign cast in his features. His keen dark eyes were searching everywhere, while the clothes he wore were the clothes of a man of refined taste.

From time to time there played about his dark face a sinister smile – a smile of triumph. He was evidently not a man to be trifled with, and it seemed very much as though he held the owner of that comfortable house in resentment.

The words he muttered as he stood there pretending to read were, in themselves, sufficient indication of this:

“They thought to trick him – to trick me – but by Jove, they’ll find themselves mistaken!” and his claw-like hand gripped the newspaper until it trembled in his grasp.

He lit a cigarette, and twice crossed the road. Standing at the corner of Pembridge Gardens, he again looked up the street, dark, misty, and deserted on that winter’s night.

“They laugh at us without a doubt,” he muttered to himself. “They laugh, because they think he’s fool enough to give away the secret. Yes, they take him for a blind idiot. Frank Farquhar has gone upon a fool’s errand to Denmark, intending to ‘freeze us out’ of what is justly ours. When he returns, he will find that I have checkmated both him and his friend Griffin, in a manner in which he little expects.”

His countenance was full of craft and cunning; his smile was sufficient index to his character.

Soon after ten o’clock, while standing at the corner of Pembridge Gardens, he suddenly drew back into the shadow, turned upon his heel and crossed the road to the station, in order to avoid notice.

Having gained the opposite pavement, he drew back again into the shadow, and saw a female figure in a short dark skirt, and wearing a handsome white fox boa, hurrying across the road in his direction.

She passed him, and he for the first time caught sight of her pretty face. It was Gwen Griffin.

Apparently she was in a frantic hurry, for she rushed into the booking-office and in her haste to get a ticket, dropped her purse. Then, when she had run down the stairs to the platform, the silent watcher followed leisurely, obtained a ticket for Earl’s Court, but was careful not to gain the platform until the girl had already left.

“I thought the story would alarm her,” he laughed to himself as he stood awaiting the next “Circle” train. “Ah, my fine young fellow, you’ve made a great and a most fatal error!” he added with a dry laugh, as he paced the platform.

Chapter Fourteen

In which Owen Becomes Anxious

When just on the point of retiring, the maid had brought Gwen up a telegram from Frank, stating that something serious had occurred, that he had returned to London unexpectedly, and that he was unable to come to the house as he preferred not to meet her father, and urging her to meet him at Earl’s Court Station at a quarter past ten that night.

In greatest alarm, and wondering what could possibly have occurred, the girl had dipped on the first things that had come to her hand and had dashed out to meet her lover.

Before going forth she had taken the maid into her confidence, saying:

“I have to go out, Laura. You need not mention anything to my father. Leave the front door unbolted. I will take the latch-key.”

The dark-eyed girl, with whom Miss Gwen was a great favourite, promised to say nothing, and had let her young mistress quietly out.

Gwen was puzzled why Frank should appoint to meet her at Earl’s Court. If the interview was to be a secret one, why had he not committed a breach of the convenances and asked her to his rooms? She had been there to tea once – in strictest secrecy, of course – but in company with a girl friend.

What untoward circumstances could have arisen to bring Frank back before he reached Copenhagen? He could not have got further than Hamburg, she reflected – if as far.

At Earl’s Court she alighted, and having ascended the stairs in eager expectation, passed through the booking-office into the Earl’s Court Road, expecting her lover to meet her.

But she was disappointed. He was not there. She glanced at the railway dock, and saw that it was already twenty-five minutes past ten. The receipt of the strange message had upset her. She felt that something terrible must have occurred if Frank “preferred” not to face her father. What could it be? She was half frantic with fear and apprehension.

From out the misty night the tall man standing in the shadow on the opposite side of the road was watching her every movement. At the kerb stood a taxi-cab which he had hailed, and now kept waiting. He had remarked to the driver that he expected a lady and would wait until she arrived.

For fully a quarter of an hour he allowed the girl to pace up and down the pavement outside the station, waiting with an impatience that was apparent. That message which she believed to be from Frank had filled her mind with all sorts of grave apprehensions. He would surely never appoint that spot as a meeting place if secrecy were not imperative.

She noticed that there were quiet deserted thoroughfares in the vicinity. There he no doubt intended to walk and explain the situation.

Yet why did he not come, she asked herself. Already he was half an hour late, while she, agitated and anxious, could scarcely contain herself.

Suddenly, however, a tall good-looking man in a dark overcoat stood before her and raised his silk hat. She was about to step aside and pass on when the man begged her pardon, and uttered her name, adding:

“I believe you are expecting my friend, Frank Farquhar?”

“Yes,” she replied. “I – I am.” And she regarded the stranger inquiringly.

“He has sent me, Miss Griffin, as he is unfortunately unable to keep the appointment himself?”

“Sent you – why?” asked the girl, looking him straight in the face.

“He has sent me to tell you that something unexpected has happened,” replied the man.

“What has occurred?” she gasped. “Tell me quickly.”

“Well,” he said with some deliberation. “I do not know whether you are aware that Mr Farquhar was interested in a great and remarkable secret – a secret which he was occupied in investigating?”

“Yes,” she answered quickly. “I know all about it. He told me everything.”

“The contretemps which has occurred is in connection with that,” the stranger said. “He was on his way to Copenhagen, but was compelled to return. He has, I believe, gained the key to some extraordinary cipher or other, and therefore he wishes to see you at once, and in secret. He told me that at present his return to London must be kept confidential, as there are other unscrupulous people most anxious to learn the truth upon which such enormous possibilities depend.”

“He wants me to go to him,” the girl cried. “Where is he then?”

“Not far away,” the man replied. “If you will allow me to escort you, I will do so willingly, Miss Griffin.”

The girl hesitated. She naturally mistrusted strange men. He saw her hesitation, and added:

“I trust you will forgive me for not being with you at the time Frank appointed, but – well, I don’t wish to alarm you unduly, but he was not very well. I was sitting with him.”

“Then he’s ill!” she cried in alarm. “Tell me. Oh! do tell me what has occurred.”

“He will tell you himself,” was the ingenious reply. “But,” he added, as though in afterthought, “I ought to have given you my card.” And he produced one and handed it to her. The name upon it was “William Wetherton, Captain, 12th Lancers.”

“Do relieve my anxiety, Captain Wetherton,” the girl implored. “Tell me what has happened.”

“As I have already said, Farquhar has made a great discovery, and wishes at once to consult you. His indisposition was only temporary – an attack of giddiness,” he added, and he saw that she was wavering. “I’m an old friend of Frank’s,” he went on, “and he consulted me, as soon as the matter of the Hebrew secret came into his hands. Of course, he has very often mentioned you,” he laughed.

He was a well-spoken man, and beneath his smile the girl did not detect his cunning. Her natural caution was overcome by her frantic desire to see Frank, and hear what he had discovered. An instant’s reflection showed her that if he could not meet her it was only natural that he should send his friend Captain Wetherton – a man of whom he had spoken on several occasions. He was stationed at Hounslow, Frank had told her, and they often spent the evening together at the club and some “show” afterwards.

“There’s a ‘taxi’ across the way,” the Captain pointed out. “Let us take it – that is if I may be permitted to be your escort, Miss Griffin?”

“Is it far?”

“Oh, dear no,” he laughed, and raising his hand he called the cab he had already in waiting. The vehicle drew across, and as he entered after her he spoke to the man. He had already given him the address before he had approached her. As he sat by her side, the man’s face changed. In the semi-darkness she could not get a good look at his features, yet his chatter was gentlemanly and good-humoured. From his remarks it was apparent that he had known her lover for a long time, and held him in high esteem.

“As soon as Frank’s telegram arrived, I rushed out,” said the young girl. “It was a great surprise, for I believed him to be on his way to Copenhagen.”

“They’ll probably miss you at home, won’t they?” he asked, with a glance of admiration at the girl’s sweet face.

“Well,” she laughed, “my father doesn’t know I’m out. Laura, the maid, will leave the door unbolted and I’ve got the latch-key.”

The man seated at her side smiled, turning away his head lest she might wonder.

Acquainted as Gwen was with the streets of the West End, she saw that the course taken by the “taxi” was through Brompton Road and Knightsbridge to Hyde Park Corner, then straight up South Audley Street and across one of the squares, Grosvenor Square she believed it to be.

“Why isn’t Frank at his own rooms in Half Moon Street?” she asked with some curiosity.

“Because, having discovered the secret, he is now in fear of his rivals, so is compelled to go into hiding. I, alone, his best friend, know his whereabouts. Quite romantic, isn’t it?” he laughed.

“Quite. Only – well, only – Captain Wetherton, I do wish you would tell me what has really occurred. I feel that you are keeping something from me.”

“I certainly am, Miss Griffin,” was his prompt reply, a reply which contained more meaning than he had intended. “Frank, in sending me to you, made the stipulation that he should have the pleasure of telling you himself. All I can say is that I believe the knowledge of the secret will be the means of bringing to him wealth undreamed of, and a notoriety world-wide.”

He was purposely keeping her engrossed in conversation, in order that they might cross Oxford Street; hoping that in the maze of turnings beyond that main thoroughfare she might lose her bearings.

Suddenly the “taxi” pulled up with a jerk before a closed shop, in a dark, rather unfrequented but seemingly superior street, and the Captain opened the side door with his latch-key, disclosing a flight of red-carpeted stairs.

“Here are my rooms,” Wetherton explained. “Frank has sought refuge with me here. He is upstairs.”

Gwen ascended the stairs quickly to the second floor, where the Captain opened the door with his key, and a moment later she found herself in a large, well-furnished bachelor’s sitting-room where the electric lamps were shaded with yellow silk.

It was evidently the room of a man comfortably off, for the furniture had been chosen with taste, and the pretty knick-knacks and quaint curios upon the table showed the owner of the place to be a man of some refinement.

“Where is he?” inquired the girl, looking around blankly, her cheeks flushed with excitement.

The man turned upon her, and laughed roughly in her face.

She drew back in horror and alarm when, in an instant, she realised how utterly helpless she now was in the stranger’s hands. He had closed the door behind him and pushed back the bolt concealed beneath the heavy portiere.

“He is not here!” she gasped. “You’ve – you’ve lied to me. This is a trick!” she gasped.

“Pray calm yourself, my dear little girl,” he said, coolly lighting a cigarette. “Sit down. I want to have a quiet chat with you.”

“I will not, sir!” she answered, with rising anger. “Allow me, please, to go. I shall tell your friend Mr Farquhar of this disgraceful ruse.”

“You can tell him, my dear girl, whatever you please,” the fellow laughed insolently. “As a matter of fact, your lover does not know me from Adam. So you see it’s quite immaterial.”

“It is not immaterial,” she declared, with a fierce look of resentment: “You shall answer to him for this!”

“Possibly it will be you who will be compelled to answer to him, when he knows that you have accompanied me here alone to my rooms, at eleven at night – eh? What will your lover say to that, I wonder?”

“I have the telegram,” she cried, opening the little bag she carried.

It was not there!

“See,” he laughed. “I have the telegram!” And before her eyes he tossed it into the fire.

She bent to snatch it from the flame, but he seized her white wrist roughly and threw her backward upon the hearthrug. He had extracted the message from her bag as they had sat together in the darkness of the cab.

Struggling to her feet she screamed for help, and fought frantically with the man who had decoyed her there; fought with the fierce strength of a woman defending her dearest possession, her honour.

She saw how the man’s countenance had changed. There was an evil expression there which held her terrified.

She begged mercy from him, begged wildly upon her knees, but he only laughed in her face in triumph. She saw, now that the telegram was destroyed, that this man who had posed as Frank’s friend could make his vile story entirely complete.

She was helpless in the hands of a man whose very face betrayed his vile unscrupulousness.

In the struggle she felt his hot foetid breath upon her cheek. Her blouse of pale blue crêpe-de-chine was ripped right across the breast as she endeavoured to wrench herself from his grasp.

“Ah! Have mercy on me!” she screamed. “Let me go! Let me go! I’ll give you anything – I – I – I’ll be silent even – if you’ll only let me go! Ah! do – if you are a gentleman!”

But the fellow only laughed again, and held her more tightly.

Her bare chest heaved and fell quickly before him. Her breath came and went.

“You think,” he said in a cruel hard voice, “you think your lover will not believe me. But I see upon your flesh a mark – a natural blemish that you cannot efface. Listen to me quietly. Hear me, or else I shall tell him of its existence, and urge him to discover whether or not I have spoken the truth. Perhaps he will then believe me!”

“You brute!” cried the girl in sudden and breathless horror. “You blackguard! you intend to ruin me in Frank’s eyes. Let me go, I say! Let me go.” Again she struggled, trying to get to the window, but with his strong arms encircling her she was helpless as a child, for with a sudden effort he flung her backwards upon the couch, inert and senseless.

Chapter Fifteen

Reveals the Rivals

Sir Felix Challas, Baronet the well-known financier and philanthropist, was seated in his cosy library in Berkeley Square, dictating letters to his secretary between the whiffs of his mild after-breakfast cigar. He was a man of middle age, with slight side whiskers, a reddish face, and opulent bearing. In his frock-coat, fancy vest, and striped trousers, and white spats over his boots, he presented the acmé of style as far as dress was concerned. The whole world knew Sir Felix to be something of a dandy, for he had never, for the past ten years or so, been seen without a flower in his buttonhole. Like many another man in London he had amassed great wealth from small beginnings, until he was now a power in the world of finance, and as a philanthropist his name was a household word.

From a small leather shop somewhere in the Mile End Road he had risen to be the controlling factor of several of the greatest financial undertakings in the country; while the house of Challas and Bowen in Austin Friars was known in the City as one of the highest possible standing.

Though he owned that fine house in Berkeley Square, a beautiful domain in Yorkshire which he had purchased from a bankrupt earl, a villa at Cannes, racehorses, motors, and a splendid steam-yacht, he was still a bachelor, and a somewhat lonely man.

The papers mentioned his doings daily, gave his portrait frequently, and recorded with a flourish of trumpets his latest donation to this charity, or to that. Though he made enormous profits in his financial deals, yet he was a staunch churchman, his hand ever in his pocket for the various institutions which approached him. Indeed, if the truth were told, he, like others, had bought his birthday Baronetcy by making a princely donation to the Hospital Fund. This showed him to be a shrewd man, fully alive to the value of judicious advertisement.