полная версия

полная версияCora and The Doctor: or, Revelations of A Physician's Wife

I was obliged to put my arm around my distressed friend. She looked ready to faint; but holding strong volatile salts to her nose, she endeavored to control her feelings. Frank and myself regretted extremely that the Attorney General thought it necessary to summon her as a witness.

The court opened. The Clerk read the Docket, from which it appeared that the Grand Jury had found three bills against the prisoners at the bar; for conspiracy in obtaining property under false pretences – for wilful perjury – and for fraud.

On motion of the Attorney General, it was ordered that they should be tried upon the first of these, as it related to the primary, and principal crime. The Clerk called upon the prisoners to arise and attend to the indictment on which they were arraigned.

"COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS"County of – . At the Court of Common Pleas, begun and holden in Crawford, within the County of – , on the first Monday, being the fourth day of November, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and forty-four.

"The Grand Jurors for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, upon their oath present that Joseph Lee, and Oscar Colby, gentlemen, of the town of Crawford, in the county of – , not having the fear of God before their eyes, and being moved by an evil heart, and seduced by the instigations of the devil, on or about the first day of November, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and thirty-seven, in the town, county and commonwealth aforesaid, did wilfully and maliciously conspire together to secrete or destroy the last will and testament of one Joseph Lee deceased, of said town, county and commonwealth aforesaid. And did thereby feloniously and wilfully arrest the course of justice in the settlement of the estate of the deceased Joseph Lee, by setting up, and subsequently executing as his last will and testament, a will prior to his last, and thereby defrauding his legal heir or heirs, and so the Jurors upon their oath aforesaid do say that the said Joseph Lee, and Oscar Colby then and there, in the manner aforesaid, did commit the crime of conspiracy as aforesaid, against the peace of the Commonwealth aforesaid, and the laws in such cases made and provided.

A true bill.

James Frothingham, Foreman.John Marshall, Attorney General."To this indictment the prisoners plead "not guilty." The Clerk then proceeded to impanel the jury.

Moses Willard, District Attorney, appeared and took his seat. The counsellors for the defendants were Edgar Burke, and Sylvanus Curtiss.

Clerk of the Court. "Gentlemen of the Jury, hearken to the indictment found against Joseph Lee, and Oscar Colby."

Here the Clerk read the indictment to the Jury, when he continued: "To this indictment, the defendants have plead not guilty, and have put themselves on the country, which country you are, and you are now sworn to try the issue."

District Attorney. "You perceive, Gentlemen of the Jury, by the indictment that has been read to you that Joseph Lee and Oscar Colby are charged by the Grand Jury of the body of this county with conspiracy to defraud, a crime punishable with the severest penalties of the law, and alleged by the indictment to have been committed by them feloniously, wilfully and maliciously. I need not portray to you the sad consequences which have already resulted from this villany.

"We intend to prove that the prisoners at the bar did at the time and place specified in the indictment, conspire together to destroy the last will and testament of one Joseph Lee deceased, and to set up as his last will and testament, a will prior to his last, and did thereby deprive his dutiful daughter of her patrimony, – a daughter who had for years administered to her sick father's necessities, smoothing by her affectionate care his passage to the grave; and that they drove her from the home of her childhood and youth on the very eve of her deceased father's burial, rendering her houseless, and shelterless, but for the protecting arm of her newly wedded companion.

"We intend to prove the sad consequences of this crime to the prisoners themselves."

Mr. Curtiss. "Your Honor, I must object to this appeal to personal sympathy, and personal prejudice."

District Attorney. "Your Honor, I beg not to be interrupted. I was only stating what the prosecution intend to prove. I was specifying the consequences of crime to the prisoners at the bar; but I forbear. The bloated face, and blood-shot eyes of the one, and the ghastly pallor of the other, speak far more than any words I could utter.

"Gentlemen of the Jury, I have no need to caution you against participating in the popular indignation at this crime, or not to fear the consequences of a faithful discharge of your whole duty. Your oath requires you to decide the question of the guilt or innocence of the prisoners according to law and evidence.

"The indictment charges them with Conspiracy. But, gentlemen, I will not detain you farther, except to cite authorities respecting the nature of this crime, the laws and penalties pertaining thereunto, and also to remark on the confidence to be placed in the confession of a dying man, which will soon be submitted to you."

He then proceeded to read from Roscoe on Criminal evidence, Chitty's Criminal Law, Archbold, etc., etc. After which, he concluded by saying, "This charge we expect to prove by the confession of Hugh Fuller on his death bed, where we naturally expect the utmost sincerity, and where there could be no motive for self-accusation, and a confession of that which must forever tarnish the fair fame of the confessor, – no motive falsely to criminate his fellow men. His testimony is entitled to the highest consideration, supported as it will be by an array of circumstantial evidence, amounting almost to a moral demonstration."

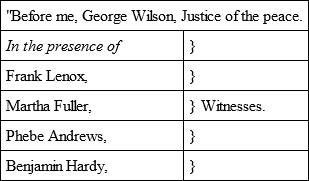

He then called George Wilson, Justice of the peace, who after being sworn read the Affidavit, as he took it from the lips of the dying man.

AFFIDAVIT"COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS"County of – ss. Hugh Fuller of Crawford, in said county, yeoman, personally before me, and lying upon his death-bed, on oath declared that he affixed his name as witness to the last will and testament of the late Joseph Lee of said town and county, then lying on his death-bed, on the twenty-third of October, one thousand eight hundred and thirty-seven. And also at the same time and place affixed his signature to a deed by the said Joseph Lee, conveying property from him to widow Churchill.

"And the deponent farther declares, that the other witnesses of these documents were Oscar Colby, and Edward Stone.

"The deponent also solemnly declares that the papers were then delivered by said Joseph Lee to said Oscar Colby with instructions that the first document should be retained by him, Oscar Colby, until after the testator's decease, and that the second should be immediately conveyed by said Colby to the aforesaid Widow Churchill.

"The deponent still farther declares that the said Oscar Colby enjoined upon him and Edward Stone, now deceased, profound secrecy in respect to the first of these transactions; and that immediately upon the death of the late Joseph Lee, the said Colby came to him renewing the injunction with a proffer of money, as reward for so doing; and that both he and Joseph Lee, son of the deceased Joseph Lee, subsequently came to him to instruct him how to appear, and what to say, if cited before the Probate Court; and at the same time paid him certain sums of money in consideration of his maintaining such secrecy.

"And the deponent also declares that his abetting of this crime has ever since lain heavily upon his conscience, and has at times harrowed his soul with the most dreadful remorse; and that he cannot die in peace until he has made a frank, and full confession of this sin, and implored forgiveness of God, and his fellow men; more particularly of those whom he has thus injured.

"All this, the deponent declares to be true in the presence of that God before whom he expects in a few moments to appear; and the same was subscribed and sworn to on this fourth day of September, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and forty-four.

Hugh Fuller.

In corroboration of this testimony, the following witnesses were called and sworn:

Frank Lenox, Allen Mansfield, Lucy Lee Mansfield, Susan Burns, Jacob Strong, who bore testimony similar to that given by them before the Probate Court, and showing the oft declared intention of the late Joseph Lee to revoke his first will, and to make a second.

They also testified that up to the time of the alleged crime, the prisoners were comparative strangers, and that from that period, they had been leagued together in the closest alliance; first in the house of the late Joseph Lee immediately after his funeral, then in the execution of the will, and subsequently in a voyage to Europe, from which they lately returned together after an absence of some years; and finally that they were together up to the time of their arrest.

To reveal the nature of their intercourse when together, Jacob Strong, steward of the late Joseph Lee, testified, that on the evening after the funeral of his master, his son Joseph, and Lawyer Colby were together in the back parlor of his master's residence, where they called for wines, brandy and cigars, and where they spent most of the night in drunkenness.

And he farther testified that at sundry times during the succeeding month, he had been often awaked at late hours of the night, by their midnight carousals; and alarmed by their abuse of each other. And that he had often interposed to separate and quiet them.

Here the prosecution closed the presentation of the case in behalf of the government, reserving the right to introduce rebutting testimony.

It being past twelve o'clock, the court adjourned till two P. M.

Two o'clock, P. M. Tuesday afternoon. The Court met pursuant to adjournment.

The defence opened. Mr. Curtiss arose. "Hay it please your Honor, and you, Gentlemen of the Jury, I arise under no small embarrassment to plead the cause of my clients in this important trial, – an embarrassment which arises from the overwhelming tide of public indignation, which in its mighty current, and irresistible force threatens to carry away every barrier of public justice, and public safety.

"Upon the alleged confession of Hugh Fuller this tide deluged the surrounding country, as when the dam of a great river is carried away, and the pent up waters are let loose, bearing down all before them.

"We, Witnesses, Counsellors, and Jurors are in no small danger of being carried away as float-wood whither the mighty torrent shall bear us.

"I cannot resist the conviction that the District Attorney, by his quick sympathies, has so far participated in this popular feeling, that he has not in this case sustained his deservedly high reputation for equity, and impartiality. My great esteem for him as an advocate led me to expect that he would devote to this exciting trial, his characteristic calmness, and discrimination, that he would carefully weigh the evidence, and avoid all appeals to passion or prejudice. Judge then of my surprise that in the very beginning of his speech, he should appeal to your sympathy in behalf of the daughter of the late Joseph Lee.

"Gentlemen of the Jury, you are here for the exercise, not of sympathy, but of justice. And my astonishment was increased by his attempt to awaken your prejudices against my clients, by reference to any peculiarities in their personal appearance. What honest citizen; nay, what one of you could be suddenly dragged from your bed at night, and committed to prison on such a charge; be brought from your cell handcuffed and strongly guarded, and here locked up in the felon's box in the presence of so large and respectable an assembly of your fellow citizens without some emotion blanching your countenance, or flushing it with indignation.

"But my astonishment reached its highest pitch, when having waited hour after hour in painful expectation of that circumstantial testimony, which was to amount to "a moral demonstration" of my clients' guilt, and waiving in apprehension of it my right to cross examine his witnesses, I heard him acknowledge to the court that the evidence for the prosecution was in, and the case was submitted to the defence.

"His citations from legal authors, and his exposition of the laws pertaining to the crime for which my clients are arraigned meet my most cordial approbation, and supersede the necessity of any additional comments on the part of the defence. Of the three crimes charged in these indictments, the two latter are subordinate to, and dependent on the first. If there was no conspiracy, there surely could have been no wilful perjury, no suborning of witnesses in pursuance of that conspiracy.

"Setting aside the confession, what proof has been adduced to support the charge of conspiracy? None that would justify any honest citizen in cherishing a suspicion of his neighbor; none that would not blast the fairest character as with the breath of calumny. Your verdict, if you find my clients guilty, must depend almost entirely upon the credibility of a deceased witness, upon the affidavit of Hugh Fuller.

"The authorities already submitted to you by my legal friend, teach you that the testimony of a dying man should be received, if at all, with great caution. At best it is only hearsay evidence, and this is almost the only form of that species of testimony which is admissible at the bar. Before you attach to it any importance, you are bound to know that the witness at the date of the affidavit was in a sound mind, free from intellectual aberrations, and from bias of judgment.

"Has the prosecution relieved your minds from all doubt on these points? Nay, gentlemen. It has submitted no substantial proof of even the sanity of that witness. I am now prepared to prove by testimony clear and abundant that this affidavit contains nothing more than the hallucination of an insane man. This being established, I shall submit the case, after the argument of my associate, for your decision."

During the speech of Mr. Curtiss, the vast audience hung in breathless silence upon his lips; and when he resumed his seat, it was very evident that the tide of public feeling had begun to turn.

The prisoners, inspired with hope, rose from their seats, and stood leaning over the pickets of their boxes. Such was the eagerness to catch every word that the sheriff was obliged several times to rap with his pole and call "order! Order!!"

The witnesses for the defence were next called, and sworn, and examined. First, Frank Lenox.

Mr. Curtiss. "What is your profession?"

"I am a physician."

"How long have you been in practice?"

"About thirteen years."

"Was Hugh Fuller your patient?"

"He was."

"What was his disease?"

"Typhoid fever."

"Have you been familiar with that fever in your practice?"

"I have had many cases every year."

"How have you commonly found the reason affected by this disease?"

"The mind is frequently subject to aberration, but more frequently in the typhus, than in the typhoid fever."

"Had you any reason to think the mind of Mr. Fuller was thus affected by his disease?"

"At times his language was strange, and his thoughts incoherent. But he was more free from aberration than patients generally in that fever."

"How near the date of his alleged confession, do you remember to have witnessed any such wanderings?"

"I think his mind was rather wandering on the previous morning."

Mr. Burke. "Had you given him medicine from which unnatural excitement could result?"

"I had not."

Cross examination by Mr. Willard.

"Did you consider him of sound mind and memory on the night of his confession?"

"I did."

"How did he appear after the confession?"

"Very much relieved. – calm and peaceful."

"Are you confident that his mental aberrations resulted from his disease?"

"I considered them in a great measure the result of a troubled conscience."

Mr. Curtiss sprang to his feet, and said, "May it please your Honor, I must object to that question. It calls forth a reply not legitimate to the profession of the witness. Cases of conscience belong to the Clergy."

Judge. "The witness will proceed, confining himself to facts pertaining to the case."

Mr. Marshall, the Attorney General, asked, "was there any particular subject on which his mind seemed to be dwelling in what you supposed mental aberrations?"

Mr. Burke arose under considerable excitement. "Your Honor, I must protest against the introduction of testimony going to show the subject of a crazy man's thoughts."

Mr. Marshall stood waiting to reply. "Your Honor will consider the special importance of this testimony as showing the state of the confessor's mind, and the subject which principally occupied his thoughts."

After a prolonged discussion of the admissibility of this testimony by the learned counsellors, the Judge decided the question in order, and directed the witness to proceed.

"He often repeated the words, 'that's all I remember; they can't take me up for that. And if they do, I'm not answerable; they that hired me will have to bear the blame,' and so much more of the same general import that I was led to suspect," —

"Your Honor," exclaimed both the lawyers for the defence. The Junior waived, however, in favor of the Senior. "I hope your Honor will remind the witness that he is here not to relate suspicions, but facts."

Judge. "The witness may proceed and restrict himself to facts, or to such professional opinions, as are material to the case. He is to give his honest views frankly and fully."

"I was saying that I suspected, he was laboring under remorse of conscience, and I urged him, if such were the fact, to seek relief by confession."

Mr. Willard. "What was the date of this conversation?"

"At several different times. The one to which I particularly referred, took place two days before his death."

Dr. Clapp, partner of Dr. Lenox, was called, whose testimony corroborated that of the preceding witness.

Mrs. Martha Fuller was next called.

Mr. Curtiss. "What was your relation to Hugh Fuller?"

"His wife."

"Did you discover anything during your husband's sickness which led you to think him insane?"

"I did."

"At what part of it more particularly?"

"The latter part."

"What did he say that led you to infer that he was crazy?"

"Sometimes he did not know me, called me by another name, talked wildly, and was frequently wandering in his sleep."

"How near the time of this alleged confession did you notice any signs of insanity?"

"On the night and day preceding his death."

Cross examination by Mr. Willard.

"Did you hear your husband's confession?"

"I did."

"Did you consider him crazy at that time?"

Hesitating. "I did not."

"What reasons had you for not considering him so?"

"He called us all by name, and talked rationally about other things, and gave me directions about the children."

"Had he frequently talked with you in this way during his sickness?"

"He had not."

"But during his sickness, had there not been days, or longer seasons, when he appeared rational?"

"There were."

"You have said he was often wild and wandering. Do you mean he was so most of the time, or only now and then?"

"Only now and then."

"Had he ever appeared so before this sickness?"

Witness bursts into tears.

Mr. Curtiss. "Your Honor, I claim the protection of the Court in behalf of this witness."

Mr. Marshall. "Your Honor, we have no disposition to impose upon the witness, who certainly has our tenderest sympathy in these trying circumstances. But the question of my worthy colleague was designed to elicit from the witness, the fact whether or not her lamented husband previous to his last sickness, had ever exhibited signs of insanity?"

Mr. Burke. "Your Honor, I object to the question as irrelevant."

Judge. "The question is pertinent and the witness will answer according to her best recollections."

Witness. "I cannot say that he did."

Mr. Willard. "Did he ever appear depressed in spirits?"

"He did."

"Can you recollect what he used to say at such times?"

She weeps.

"Take your time, my good woman." The sheriff at a motion from Mr. Willard brings her a chair. "Try to recollect what he said at such times."

"He used to fear we should come to poverty and disgrace."

"Did he ever explain the ground of those fears?"

"He did not, when awake."

"What do you mean to imply by that?"

"He sometimes talked about it in his sleep; but I couldn't always make out what he said."

"Did the drift of his conversation at such times correspond with that when he was wild and wandering during his sickness?"

"I think it did."

The Court was then adjourned until nine o'clock the next morning.

CHAPTER XXXI

"As lawyers o'er a doubtWhich, puzzling long, at last, they puzzle out." Cowper.Wednesday, November 6th.Nine o'clock. The Court met pursuant to adjournment. The excitement has much increased. The court-room is crowded to its utmost capacity, and the most intense interest manifested as to the decision.

Mr. Andrews was called and sworn.

Mr. Curtiss. "Did you frequently see Hugh Fuller during his sickness?"

"I watched with him twice."

"Have you often watched with persons in this fever?"

"I have."

"How were their minds affected?"

"They were generally deranged."

"Did you witness any appearance of insanity in Mr. Fuller?"

"I did."

"How was it manifested?"

"He once imagined I was his mother, and that I was instructing him. Another time he thought he was building a house, and called out to his workmen about the work."

Before the cross examination, I noticed Mr. Willard speaking in a low voice to Mr. Marshall, when he took his hat and retired from the court-room.

Mr. Marshall. "Do you mean to convey the idea that Mr. Fuller was not rational during any part of the nights that you watched with him?"

"By no means, sir. I mean that he was a little out of his head."

"Did he recognize you?"

"He did, and often called me by name, and told me what medicine he was to take."

"When he thought you were his mother, what did he say?"

"He said he remembered my instructing him to tell the truth, and how much happier he should have been if he had regarded my instructions."

Mrs. Andrews was called.

Mr. Curtiss. "Did you see Mr. Fuller during his sickness?"

"I watched with him the night before he died."

"How did he appear at that time?"

"The first part of the night, he took me to be his wife, and talked with me about the children."

"Relate all you remember of his wanderings."

"He was very much excited and wanted to get out of bed and go to see Dr. Lenox – Said he must go, and we had great difficulty in pacifying him."

Cross examination.

Mr. Marshall. "Do you remember what he said to you about the children?"

"He charged me never to let the girls marry a man who had perjured himself."

This reply produced great sensation, and the sheriff again thundered "order! ORDER!!"

"Did he appear more calm toward morning?"

"Oh, no! He grew more and more excited until we promised to send for the Doctor."

"Did that wholly pacify him?"

"He seemed so relieved and rational that I staid alone with him while Mr. Hardy went for the Doctor, and he hardly spoke during his absence."

"How did he appear during that time?"

"He lay with his eyes closed, and once I thought I heard the words. 'Oh, God! – Oh, Jesus, forgive me!'"

Mr. Curtiss called Mr. Hardy. "Did you discover any signs of insanity in Mr. Fuller on the night preceding his death?"

"I did."

"What were they?"

"Substantially those already testified to by Mrs. Andrews. He called incessantly for the Doctor, saying he could not die till he had seen him."