полная версия

полная версияThe Ladies' Guide to True Politeness and Perfect Manners

If a foreigner chances, in your presence, to make an unfavourable remark upon some custom or habit peculiar to your country, do not immediately take fire and resent it; for, perhaps, upon reflection, you may find that he is right, or nearly so. All countries have their national character, and no character is perfect, whether that of a nation or an individual. If you know that the stranger has imbibed an erroneous impression, you may calmly, and in a few words, endeavour to convince him of it. But if he shows an unwillingness to be convinced, and tells you that what he has said he heard from good authority; or that, before he came to America, "his mind was made up," it will be worse than useless for you to continue the argument. Therefore change the subject, or turn and address your conversation to some one else.

Lady Morgan's Duchess of Belmont very properly checks O'Donnell for his ultra-nationality, and advises him not to be always running a tilt with every Englishman he talks to, continually seeming as if ready with the war-cry of "St. Patrick for Ireland, against St. George for England."

Dr. Johnson was speaking of Scotland with his usual severity, when a Caledonian who was present, started up, and called out, "Sir, I was born in Scotland." "Very well, sir," said the cynic calmly, "I do not see why so small a circumstance should make any change in the national character."

English strangers complain (and with reason) of the American practice of imposing on their credulity, by giving them false and exaggerated accounts of certain things peculiar to this country, and telling them, as truths, stories that are absolute impossibilities; the amusement being to see how the John Bulls swallow these absurdities. Even General Washington diverted himself by mystifying Weld the English traveller, who complained to him at Mount Vernon of musquitoes so large and fierce that they bit through his cloth coat. "Those are nothing," said Washington, "to musquitoes I have met with, that bite through a thick leather boot." Weld expressed his astonishment, (as well he might;) and, when he "put out a book," inserted the story of the boot-piercing insects, which he said must be true, as he had it from no less a person than General Washington.

It is a work of supererogation to furnish falsehoods for British travellers. They can manufacture them fast enough. Also, it is ungenerous thus to sport with their ignorance, and betray them into ridiculous caricatures, which they present to the English world in good faith. We hope these tricks are not played upon any of the best class of European travel-writers.

When in Europe, (in England particularly,) be not over sensitive as to remarks that may be made on your own country; and do not expect every one around you to keep perpetually in mind that you are an American; nor require that they should guard every word, and keep a constant check on their conversation, lest they should chance to offend your republican feelings. The English, as they become better acquainted with America, regard us with more favour, and are fast getting rid of their old prejudices, and opening their eyes as to the advantages to be derived from cultivating our friendship instead of provoking our enmity. They have, at last, all learnt that our language is theirs, and they no longer compliment newly-arrived Americans on speaking English "quite well." It is not many years since two young ladies from one of our Western States, being at a party at a very fashionable mansion in London, were requested by the lady of the house to talk a little American; several of her guests being desirous of hearing a specimen of that language. One of the young ladies mischievously giving a hint to the other, they commenced a conversation in what school-girls call gibberish; and the listeners, when they had finished, gave various opinions on the American tongue, some pronouncing it very soft, and rather musical; others could not help saying candidly that they found it rather harsh. But all agreed that it resembled no language they had heard before.

There is no doubt that by the masses, better English is spoken in America than in England.

However an Englishman or an Englishwoman may boast of their intimacy with "the nobility and gentry," there is one infallible rule by which the falsehood of these pretensions may be detected. And that is in the misuse of the letter H, putting it where it should not be, and omitting it where it should. This unaccountable practice prevails, more or less, in all parts of England, but is unknown in Scotland and Ireland. It is never found but among the middle and lower classes, and by polished and well-educated people is as much laughed at in England as it is with us. A relative of ours being in a stationer's shop in St. Paul's Church Yard, (the street surrounding the cathedral,) heard the stationer call his boy, and tell him to "go and take the babby out, and give him a hairing– the babby having had no hair for a week." We have heard an Englishman talk of "taking an ouse that should have an ot water pipe, and a hoven." The same man asked a young lady "if she had eels on her boots." We heard an Englishwoman tell a servant to "bring the arth brush, and sweep up the hashes." Another assured us that "the American ladies were quite hignorant of hetiquette."

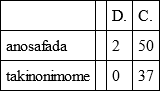

We have actually seen a ridiculous bill sent seriously by a Yorkshireman who kept a livery-stable in Philadelphia. The items were, verbatim—

No reader can possibly guess this – so we will explain that the first line, in which all the words run into one, signifies "An orse af a day," – or "A horse half a day." The second line means "takin on im ome," – or "Taking of him home."

English travellers are justly severe on the tobacco-chewing and spitting, that though exploded in the best society, is still too prevalent among the million. All American ladies can speak feelingly on this subject, for they suffer from it in various ways. First, the sickening disgust without which they cannot witness the act of expectoration performed before their faces. Next, the danger of tobacco-saliva falling on their dresses in the street, or while travelling in steamers and rail-cars. Then the necessity of walking through the abomination when leaving those conveyances; treading in it with their shoes; and wiping it up with the hems of their gowns. We know an instance of the crown of a lady's white-silk bonnet being bespattered with tobacco-juice, by a man spitting out of a window in one of the New York hotels. A lady on the second seat of a box at the Chestnut-street theatre, found, when she went home, the back of her pelisse entirely spoilt, by some man behind not having succeeded in trying to spit past her – or perhaps he did not try. Why should ladies endure all this, that men may indulge in a vulgar and deleterious practice, pernicious to their own health, and which they cannot acquire without going through a seasoning of disgust and nausea?

It is very unmannerly when a person begins to relate a circumstance or an anecdote, to stop them short by saying, "I have heard it before." Still worse, to say you do not wish to hear it at all. There are people who set themselves against listening to any thing that can possibly excite melancholy or painful feelings; and profess to hear nothing that may give them a sad or unpleasant sensation. Those who have so much tenderness for themselves, have usually but little tenderness for others. It is impossible to go through the world with perpetual sunshine over head, and unfading flowers under foot. Clouds will gather in the brightest sky, and weeds choke up the fairest primroses and violets. And we should all endeavour to prepare ourselves for these changes, by listening with sympathy to the manner in which they have affected others.

No person of good feelings, good manners, or true refinement, will entertain their friends with minute descriptions of sickening horrors, such as barbarous executions, revolting punishments, or inhuman cruelties perpetrated on animals. We have never heard an officer dilate on the dreadful spectacle of a battlefield; a scene of which no description can ever present an adequate idea; and which no painter has ever exhibited in all its shocking and disgusting details. Physicians do not talk of the dissecting-room.

Unless you are speaking to a physician, and are interested in a patient he is attending, refrain in conversation from entering into the particulars of revolting diseases, such as scrofula, ulcers, cutaneous afflictions, &c. and discuss no terrible operations – especially at table. There are women who seem to delight in dwelling on such disagreeable topics.

If you are attending the sick-bed of a friend, and are called down to a visiter, speak of her illness with delicacy, and do not disclose all the unpleasant circumstances connected with it; things which it would grieve her to know, may, if once told, be circulated among married women, and by them repeated to their husbands. In truth, upon most occasions, a married woman is not a safe confidant. She will assuredly tell every thing to her husband; and in all probability to his mother and sisters also – that is, every thing concerning her friends – always, perhaps, under a strict injunction of secrecy. But a secret entrusted to more than two or three persons, is soon diffused throughout the whole community.

A man of some humour was to read aloud a deed. He commenced with the words, "Know one woman by these presents." He was interrupted, and asked why he changed the words, which were in the usual form, "Know all men by these presents." "Oh!" said he, "'tis very certain that all men will soon know it, if one woman does."

Generally speaking, it is injudicious for ladies to attempt arguing with gentlemen on political or financial topics. All the information that a woman can possibly acquire or remember on these subjects is so small, in comparison with the knowledge of men, that the discussion will not elevate them in the opinion of masculine minds. Still, it is well for a woman to desire enlightenment, that she may comprehend something of these discussions, when she hears them from the other sex; therefore let her listen as understandingly as she can, but refrain from controversy and argument on such topics as the grasp of a female mind is seldom capable of seizing or retaining. Men are very intolerant toward women who are prone to contradiction and contention, when the talk is of things considered out of their sphere; but very indulgent toward a modest and attentive listener, who only asks questions for the sake of information. Men like to dispense knowledge; but few of them believe that in departments exclusively their own, they can profit much by the suggestions of women. It is true there are and have been women who have distinguished themselves greatly in the higher branches of science and literature, and on whom the light of genius has clearly descended. But can the annals of woman produce a female Shakspeare, a female Milton, a Goldsmith, a Campbell, or a Scott? What woman has painted like Raphael or Titian, or like the best artists of our own times? Mrs. Darner and Mrs. Siddons had a talent for sculpture; so had Marie of Orleans, the accomplished daughter of Louis Philippe. Yet what are the productions of these talented ladies compared to those of Thorwaldsen, Canova, Chantrey, and the master chisels of the great American statuaries. Women have been excellent musicians, and have made fortunes by their voices. But is there among them a Mozart, a Bellini, a Michael Kelly, an Auber, a Boieldieu? Has a woman made an improvement on steam-engines, or on any thing connected with the mechanic arts? And yet these things have been done by men of no early education – by self-taught men. A good tailor fits, cuts out, and sews better than the most celebrated female dress-maker. A good man-cook far excels a good woman-cook. Whatever may be their merits as assistants, women are rarely found who are very successful at the head of any establishment that requires energy and originality of mind. Men make fortunes, women make livings. And none make poorer livings than those who waste their time, and bore their friends, by writing and lecturing upon the equality of the sexes, and what they call "Women's Rights." How is it that most of these ladies live separately from their husbands; either despising them, or being despised by them?

Truth is, the female sex is really as inferior to the male in vigour of mind as in strength of body; and all arguments to the contrary are founded on a few anomalies, or based on theories that can never be reduced to practice. Because there was a Joan of Arc, and an Augustina of Saragossa, should females expose themselves to all the dangers and terrors of "the battle-field's dreadful array." The women of the American Revolution effected much good to their country's cause, without encroaching upon the province of its brave defenders. They were faithful and patriotic; but they left the conduct of that tremendous struggle to abler heads, stronger arms, and sterner hearts.

We envy not the female who can look unmoved upon physical horrors – even the sickening horrors of the dissecting-room.

Yet women are endowed with power to meet misfortune with fortitude; to endure pain with patience; to resign themselves calmly, piously, and hopefully to the last awful change that awaits every created being; to hazard their own lives for those that they love; to toil cheerfully and industriously for the support of their orphan children, or their aged parents; to watch with untiring tenderness the sick-bed of a friend, or even of a stranger; to limit their own expenses and their own pleasures, that they may have something to bestow on deserving objects of charity; to smooth the ruggedness of man; to soften his asperities of temper; to refine his manners; to make his home a happy one; and to improve the minds and hearts of their children. All this women can – and do. And this is their true mission.

In talking with a stranger, if the conversation should turn toward sectarian religion, enquire to what church he belongs; and then mention your own church. This, among people of good sense and good manners, and we may add of true piety, will preclude all danger of remarks being made on either side which may be painful to either party. Happily we live in a land of universal toleration, where all religions are equal in the sight of the law and the government; and where no text is more powerful and more universally received than the wise and incontrovertible words – "By their fruits ye shall know them." He that acts well is a good man, and a religious man, at whatever altar he may worship. He that acts ill is a bad man, and has no true sense of religion; no matter how punctual his attendance at church, if of that church he is an unworthy member. Ostentatious sanctimony may deceive man, but it cannot deceive God.

On this earth there are many roads to heaven; and each traveller supposes his own to be the best. But they must all unite in one road at the last. It is only Omniscience that can decide. And it will then be found that no sect is excluded because of its faith; or if its members have acted honestly and conscientiously according to the lights they had, and molesting no one for believing in the tenets of a different church. The religion of Jesus, as our Saviour left it to us, was one of peace and good-will to men, and of unlimited faith in the wisdom and goodness, and power and majesty of God. It is not for a frail human being to place limits to his mercy, and say what church is the only true one – and the only one that leads to salvation. Let all men keep in mind this self-evident truth – "He can't be wrong whose life is in the right;" and try to act up to the Divine command of "doing unto all men as you would they should do unto you."

In America, no religious person of good sense or good manners ever attempts, in company, to controvert, uncalled for, the sectarian opinions of another. No clergyman that is a gentleman, (and they all are so, or ought to be,) ever will make the drawing-room an arena for religious disputation, or will offer a single deprecatory remark, on finding the person with whom he is conversing to be a member of a church essentially differing from his own. And if clergymen have that forbearance, it is doubly presumptuous for a woman, (perhaps a silly young girl,) to take such a liberty. "Fools rush in, where angels fear to tread."

Nothing is more apt to defeat even a good purpose than the mistaken and ill-judged zeal of those that are not competent to understand it in all its bearings.

Truly does the Scripture tell us – "There is a time for all things." We know an instance of a young lady at a ball attempting violently to make a proselyte of a gentleman of twice her age, a man of strong sense and high moral character, whose church (of which he was a sincere member) differed materially from her own. After listening awhile, he told her that a ball-room was no place for such discussions, and made his bow and left her. At another party we saw a young girl going round among the matrons, and trying to bring them all to a confession of faith.

Religion is too sacred a subject for discussion at balls and parties.

If you find that an intimate friend has a leaning toward the church in which you worship, first ascertain truly if her parents have no objection, and then, but not else, you may be justified in inducing her to adopt your opinions. Still, in most cases, it is best not to interfere.

In giving your opinion of a new book, a picture, or a piece of music, when conversing with a distinguished author, an artist or a musician, say modestly, that "so it appears to you" – that "it has given you pleasure," or the contrary. But do not positively and dogmatically assert that it is good, or that it is bad. The person with whom you are talking is, in all probability, a far more competent judge than yourself; therefore, listen attentively, and he may correct your opinion, and set you right. If he fail to convince you, remain silent, or change the subject. Vulgar ladies have often a way of saying, when disputing on the merits of a thing they are incapable of understanding, "Any how, I like it," or, "It is quite good enough for me." – Which is no proof of its being good enough for any body else.

In being asked your candid opinion of a person, be very cautious to whom you confide that opinion; for if repeated as yours, it may lead to unpleasant consequences. It is only to an intimate and long-tried friend that you may safely entrust certain things, which if known, might produce mischief. Even very intimate friends are not always to be trusted, and when they have actually told something that they heard under the injunction of secrecy, they will consider it a sufficient atonement to say, "Indeed I did not mean to tell it, but somehow it slipped out;" or, "I really intended to guard the secret faithfully, but I was so questioned and cross-examined, and bewildered, that I knew not how to answer without disclosing enough to make them guess the whole. I am very sorry, and will try to be more cautious in future. But these slips of the tongue will happen."

The lady whose confidence has been thus betrayed, should be "more cautious in future," and put no farther trust in she of the slippery tongue – giving her up, entirely, as unworthy of farther friendship.

No circumstances will induce an honourable and right-minded woman to reveal a secret after promising secrecy. But she should refuse being made the depository of any extraordinary fact which it may be wrong to conceal, and wrong to disclose.

We can scarcely find words sufficiently strong to contemn the heinous practice, so prevalent with low-minded people, of repeating to their friends whatever they hear to their disadvantage. By low-minded people, we do not exclusively mean persons of low station. The low-minded are not always "born in a garret, in a kitchen bred." Unhappily, there are (so-called) ladies – ladies of fortune and fashion – who will descend to meannesses of which the higher ranks ought to be considered incapable, and who, without compunction, will wantonly lacerate the feelings and mortify the self-love of those whom they call their friends, telling them what has been said about them by other friends.

It is sometimes said of a notorious tatler and mischief-maker, that "she has, notwithstanding, a good heart." How is this possible, when it is her pastime to scatter dissension, ill-feeling, and unhappiness among all whom she calls her friends? She may, perhaps, give alms to beggars, or belong to sewing circles, or to Bible societies, or be officious in visiting the sick. All this is meritorious, and it is well if there is some good in her. But if she violates the charities of social life, and takes a malignant pleasure in giving pain, and causing trouble – depend on it, her show of benevolence is mere ostentation, and her acts of kindness spring not from the heart. She will convert the sewing circle into a scandal circle. If she is assiduous in visiting her sick friends, she will turn to the worst account, particulars she may thus acquire of the sanctities of private life and the humiliating mysteries of the sick-chamber.

If indeed it can be possible that tatling and mischief-making may be only (as is sometimes alleged) a bad habit, proceeding from an inability to govern the tongue – shame on those who have allowed themselves to acquire such a habit, and who make no effort to subdue it, or who have encouraged it in their children, and perhaps set them the example.

If you are so unfortunate as to know one of these pests of society, get rid of her acquaintance as soon as you can. If allowed to go on, she will infallibly bring you into some difficulty, if not into disgrace. If she begins by telling you – "I had a hard battle to fight in your behalf last evening at Mrs. Morley's. Miss Jewson, whom you believe to be one of your best friends, said some very severe things about you, which, to my surprise, were echoed by Miss Warden, who said she knew them to be true. But I contradicted them warmly. Still they would not be convinced, and said I must be blind and deaf not to know better. How very hard it is to distinguish those who love from those who hate us!"

Instead of encouraging the mischief-maker to relate the particulars, and explain exactly what these severe things really were, the true and dignified course should be to say as calmly as you can – "I consider no person my friend, who comes to tell such things as must give me pain and mortification, and lessen my regard for those I have hitherto esteemed, and in whose society I have found pleasure. I have always liked Miss Jewson and Miss Warden, and am sorry to hear that they do not like me. Still, as I am not certain of the exact truth, (being in no place where I could myself overhear the discussion,) it will make no difference in my behaviour to those young ladies. And now then we will change the subject, never to resume it. My true friends do not bring me such tales."

By-the-bye, tatlers are always listeners, and are frequently the atrocious writers of anonymous letters, for which they should be expelled from society.

Let it be remembered that all who are capable of detailing unpleasant truths, (such as can answer no purpose but to produce bad feeling, and undying enmity,) are likewise capable of exaggerating and misrepresenting facts, that do not seem quite strong enough to excite much indignation. Tale-bearing always leads to lying. She who begins with the first of these vices, soon arrives at the second.

Some prelude these atrocious communications with – "I think it my duty to tell how Miss Jackson and Mrs. Wilson talk about you, for it is right that you should know your friends from your enemies." You listen, believe, and from that time become the enemy of Miss Jackson and Mrs. Wilson – having too much pride to investigate the truth, and learn what they really said.

Others will commence with – "I'm a plain-spoken woman, and consider it right, for your own sake, to inform you that since your return from Europe, you talk quite too much of your travels."

You endeavour to defend yourself from this accusation, by replying that "having seen much when abroad, it is perfectly natural that you should allude to what you have seen."