полная версия

полная версияThoughts on Slavery and Cheap Sugar

But we hasten to the close of this scene of death.

“As soon as the Progresso anchored, we were visited by the health officer, who immediately admitted us to pratique. My friend Mr. Shea, then superintendent of the naval hospital, also paid us a visit, and I descended with him, for the last time, to the slave hold. Long accustomed as he has been to scenes of suffering, he was unable to endure a sight surpassing, he said, ‘all he could have conceived of human misery,’ and made a hasty retreat. One little girl, crying bitterly, was entangled between the planks, wanting strength to extricate her wasted limbs, till assistance was given her.”

In a voyage of fifty days, there occurred one hundred and sixty-three deaths! Can slavery be worse than this? if this melancholy tale teaches anything, it is evidently the uselessness of armed suppression.

And yet this wretched, this utterly inefficient system, is to be continued and extended. A new remedy has been proposed by the Honourable Captain Denman, which it appears Sir Robert Peel is about to sanction. Colonel Nicolls says, it will put the slave trade down in ten or twelve months, – this we more than doubt. A blockade which, to be effectual, must extend over six thousand miles of coast, is not so easy a thing as it may seem on paper. With Lord John Russell we believe, “that to suppress the slave trade by a marine guard is impossible, were the whole British navy employed in the attempt.” A British force may burn the baracoons, but as long as the demand exists, a supply from some quarter or other will be procured. To show that the Colonel’s logic is not absolutely perfect, we quote the following fact. It was thought the destruction of the baracoons at Gallinas, in 1840, would have prevented their re-formation, but this does not appear to have been the case. The commissioners observe, “We have received information that, during the last rains, no less than three slave factories were settled in the Gallinas, whither the factors and goods had been conveyed by an American vessel.” – (Slave Trade Papers, 1843.) Destroy the nests, and the birds will not breed, says Colonel Nicolls. The gallant colonel forgets that the demand for slaves, and not the existence of baracoons, creates the slave trade; to borrow an illustration from Adam Smith, a man is not rich because he keeps a coach and four horses; but he keeps a coach and four horses because he is rich. Men make but an indifferent hand at reasoning when they are unable to tell which is the cause, and which the effect.

Had this system been attended by any the smallest amount of good, we should have kept out of account altogether the last item in this part of our subject, to which we shall refer the reader – that of expense; but when we find the money thus squandered has produced no earthly good whatever, when all parties confess that past measures have ended in utter failure, and that the slave trade, so far from being put down in all its forms of abomination and cruelty, is more vigorous than before; it is but right that we should exclaim against the waste of money that has been so lavishly incurred. Sir Fowell Buxton estimates the expense, on the part of Great Britain, in carrying out the slave trade preventive system up to 1839, at £15,000,000. We here quote from Mr. Laird:

“Her Majesty’s late commissioner of inquiry on the coast of Africa, estimates the expense incurred there, independently of the salaries and contingencies at home, of officers connected with the Anti-Slavery Treaty Department, at £229,090 per annum; and by the finance accounts, I find, that for the year ending 5th January, 1842, £57,024 was paid out of the consolidated fund, to the officers and crews of her Majesty’s ships, for bounty on slaves, and tonnage on slave vessels. These gallant men, however, do not think they get what they ought to do; for there is a long correspondence about what they lose by the way the prizes are measured for tonnage-money; but it must be consolatory to them to know that they have, in one year, received £1,000 more prize money than their predecessors did in nine; the amount of prize money paid for capturing slaves, from 1814 to 1822, being only £56,017. In fact the African station has been improving in value, as a naval command, since the slave trade treaties; it is now the bonne bouche of the Admiralty, and as such was given to the last first lord’s brothers. The mixed commission courts cost the country about £15,000 per annum; and as any dispute between the Portuguese, Spanish, or Brazilian judges is settled by an appeal to the dice box, the monotony of their lives is agreeably diversified; having retiring salaries, the patronage is valuable. The whole annual cost may be taken at £300,000.” 6

So much for this part of our subject. We may fairly conclude, that such a system is evidently vicious in principle: it has certainly failed to answer the end proposed, and the sooner it is given up the better. But let it not be for one moment understood that we consider slavery always will remain the curse and shame of humanity. We believe that it can be extinguished, – that it must be extinguished, – that, sooner or later, God’s sun shall shine every where upon the free, and that slavery shall remain alone in the dark records of earth’s misery and crime.

Freedom is the antagonist of slavery. Free labour must drive out of the market the labour of the slave. We were told before emancipation, that the former was cheaper than the latter: we have yet to learn that it is not. A glance at the present condition of the sugar-producing countries will convince any one that the West India planter has immense advantages over his rival of Cuba or Brazil.

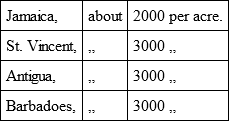

There is a great amount of misunderstanding on this subject. The soil of the West India Islands is always represented as exhausted, which is far from being actually the case. In Cuba, according to an estimate made by the patriotic society of Havanna, it appears that two hundred and fifteen acres of new land are expected to produce, in cane cultivation, thirteen hundred boxes of sugar, or 2172 lbs. per acre. We may reasonably infer, that the production in Brazil does not equal this. We find that the exports of sugar from the latter country have rather declined, while those of Cuba have been nearly doubled within the last few years; while from the evidence taken by a committee of the House of Commons, it appears that with the present imperfect system of cultivation, the following results have been obtained, including ratroons, or canes cut for several years successively. 7

A pretty fair result, it must be confessed, considering the exhausted condition of the soil. Another advantage the West India Islands possess over Brazil, arises from their facilities for water carriage. Their limited extent is anything but a drawback, – it makes them all sea coast. With labour and capital, they would be put in a position that would enable them to under-sell slave-grown sugar. The great disadvantage under which they suffer, is scarcity of labour. Antigua alone has, in this respect, a sufficient supply, and let us hear the result. The first witness we shall call is Captain Larlyle, governor of French Guiana. The captain was sent by the French government to visit most of the British West India Islands, and to see the working of the present system; the report he made has been published by government, in a work, entitled, “Abolition de l’Esclavage dans les Colonies Anglaises.” Evidently his prejudices are for the continuance of slavery, but with respect to Antigua, he was forced to bear witness of a contrary character. He observes, (our quotations are from the Anti-Slavery Reporter, of May 1st, 1844,) that “it has maintained, during the last seven years, a state of prosperity, which every impartial person cannot fail to acknowledge.” p. 189. “The exports have rather increased than diminished since emancipation.” pp. 194, 5. “If, under the system of slavery, labour had been as complete and productive as it ought to have been, if the negroes had employed the time to their best advantage, there is no doubt but they would have produced more than at present, when, in consequence of freedom, the fields have lost a third of their labourers. But I have had occasion to say, in my former reports, that forced labour has never answered the expectations that have been formed respecting it; and I find a new proof of this in the table of production in Antigua during fifteen years.” p. 196. Again, Captain Larlyle says, “If the colonists are to be believed, the plantations are worth, without the negroes, as much as they were worth formerly with their gangs of slaves.” Equally favourable is the evidence of a lady who resided in Antigua, both before and after the emancipation of the slaves, and who possessed the most ample opportunities for acquiring a knowledge of the working of either system. After referring to the depressed state of the island before the abolition of slavery, she observes:

“But this oppression did not long continue; for no sooner was the deed done, and the chain which bound the negro to his fellow-man irrecoverably snapped asunder, than it was found, even by the most sceptical, that free labour was decidedly more advantageous to the planter than the old system of slavery; that, in fact, an estate could be worked for less by free labour than it could when so many slaves, including old and young, weak and strong, were obliged to be maintained by the proprietors. Indeed, the truth of this assertion was discovered even before the negroes were free; for no sooner did the planters feel that no effort of theirs could prevent emancipation from taking place, than they commenced to calculate seriously the probable result of the change, and to their surprise found, upon mature deliberation, that their expenses would be diminished, and their comforts increased, by the abolition of slavery.”

Again, we are told, although there are some few persons who deny that free labour is less expensive than slavery, yet the general voice pronounces it a system beneficial to the country.

It has been proved to demonstration that estates which, under the old system, were clogged with debts they never could have paid off, have, since emancipation, not only cleared themselves, but put a handsome income into the pockets of their proprietors. Land was also increased greatly in value. Sugar plantations that would scarcely find a purchaser before emancipation, will now command from £10,000 sterling; 8 while many estates that were abandoned in days of slavery, are now once more in a state of cultivation, and the sugar-cane flourishes in verdant beauty where nothing was to be seen but rank and tangled weeds, or scanty herbage.

To put down slavery, then, we have only to let free labour have fair play. It is not the continuance of monopoly, but emigration, that is wanted. The first consequence of emancipation was the formation of a middle class where it had not before existed, which middle class was entirely subtracted from the agricultural population. 718,525 human beings were emancipated in our sugar colonies, including the Mauritius, of whom one-fourth were immediately absorbed in the formation of a middle class. Hence the deficiency in labour which at present affects the West India Islands. We believe, with Mr. Laird, 9 “that it is the quantity, not the quality, of labour that is wanting.” Indeed it has been shown that a free negro in Guiana creates double the amount of sugar that his enslaved countryman in Cuba does.

In many parts of the East labourers may be hired at three-halfpence and two-pence a day. From the evidence given before the West African Committee, we learn, that wages average from two-pence to four-pence a day in our three settlements on the coast of Africa. The cost of the slave in Cuba or Brazil equals this. Let the experiment be fairly tried, and it will soon be evident that slave labour must be driven out of the market. That becomes still plainer when we look at the actual condition of the slave-grown sugar. From Cuba every fresh post brings a continuance of bad news. There is a want of capital and skill – a blight rests upon the land – property and life are insecure. On March 6th, a statement appeared in the Anti-Slavery Reporter, giving an account of the wretched condition of the slaves. “We are credibly informed,” observes the editor, “that on some of the sugar plantations in Cuba the slaves are in a most miserable condition – not less than the half of a gang being sickly, covered with sores, and even cripples – the whip supplying virtue and strength, health and numbers. Unable to ‘trot’ to the field, they are placed on carts and carried to it, there to creep and toil by the help of the lash. No description can exhibit the neglect, cruelty, and inhumanity, with which they are treated. In crop-time they have no holiday – no Sunday – and no sleep!” The Times gave the following, as from Havanna, under date of February 17: – “A slaver, with 1200 negroes, has arrived on our coast. They have been offered at 340 dollars a-head, and our planters has determined to buy no more, and none of this cargo has been disposed of. No one is now inclined to encourage this abominable traffic, which begins to be considered as highly injurious to the welfare of the island. Several corporations and planters have given in reports favourable to the total abolition of the slave trade; it is understood these will be sent forthwith to the Spanish Government.”

The negroes have imbibed ideas of freedom which at no distant time will produce, by fair means or foul, a change in their condition. The planter already begins to perceive, that it is far better to be the employer of faithful and contented labourers, than the lord of men who feel their wrongs, and who wait but the first moment of revenge. Capital, the life-blood of industry, will never flow into a country till the capitalist has a pledge – a pledge no land of slaves can ever give – that the life he hazards, and the money he invests, are alike secure. Were the duty on sugar so reduced to-morrow as to put it in the power of the working man to consume as much as he required, an impulse would be given to the production of sugar which would create a demand for capital – which capital would alone be safely invested where labour is free. With a plentiful supply of labourers, no one can deny that Jamaica would be a far more eligible country for the capitalist than Cuba or Brazil; and hence the slave-trade dealers would be thrown for ever out of the markets of the world.

To put down slavery, then, we must under-sell the slave dealer. Emigration from the coast of Africa to the West Indies must be encouraged. At present wages in these islands are unnaturally high. They cannot, however, long remain so. We are glad to learn that the negroes are well off; but it cannot be expected that the West India monopoly should be continued merely that the emancipated slave may drink at his ease his Madeira or Champagne. It will be well for him if he prepares himself for the change that must shortly come. It is not to be expected that the proprietor who cultivates his estate at a loss, should continue to employ his capital without return. Unless there is a change, that capital must be withdrawn; and, thrown upon his own resources, the negro labourer will sink into a state of degradation hopeless and complete.10 Should it be found that the emigration scheme will not work well, it by no means follows that our only alternative is to continue the monopoly. A late writer11, on the state of Jamaica, expresses it as his opinion that the resources of the island are not above half developed; he declares that the implements used in the cultivation of the cane are in the most primitive state imaginable; and that were but the improvements in machines introduced there, which have obtained elsewhere, there would be no need whatever for additional labourers.

This may be true of Jamaica, but it will not apply equally to other parts of the West Indies, where labourers are needed; and Africa is the quarter to which we must naturally turn for a supply. We find men in a state of practical slavery – sunk in the lowest scale of being; and we maintain the way to humanise them, to give them habits of industry and ideas of trade, is to bring them into contact with the advanced civilisation of the west. Thanks to the labours of the missionaries, they will find their emancipated fellow-countrymen intelligent, moral, and religious men. They will become subject to the same ameliorating influences – old things will be put away, principles of good will be formed – the savage will be lost in the advancing dignity of the man.

Let the West Indian proprietor, then, take the degraded savage and convert him into a useful member of society, and in the same manner let the free-trader go and convert the slave-owner into an honest man. In both cases a restrictive policy has been found to be fraught with inevitable ill. It were time that they both should retire. Our aim should be to create in slave states a public opinion against the vile system that stains the land, and not to excite feelings of enmity against ourselves because we exclude them from our market, and seek to brand them as outcasts from society. Not by such pharisaical modes of procedure shall we obtain our end. If we would do a man good, we must teach him to look upon us as friends, and not foes. We have no right to shut up a man in his guilt; and, as a nation is but an aggregate of individuals, the principles of action that obtain in the one case must be equally valid with respect to the other. We heap contumely and scorn on the heads of the American slaveholders, and refuse to do business with the merchants of Brazil, and by such conduct directly deprive ourselves of what influence for good we might otherwise have it in our power to wield. It is time that we turn over a new leaf; that we act more in accordance with Him who makes his sun to shine, and his rain to descend, upon the good and the bad; that we speak in friendship to our fellow-man, however degraded he may be, and win him over to the adoption of that which is just and true. Experience, the great teacher of mankind, has shown in a thousand instances that in our efforts to put down slavery by restrictive policy and armed suppression, we have, at the most lavish expenditure of treasure and life, done nothing but create misery and ill-will. It is the part of a wise man to abandon a plan which he sees has entirely failed. We may, by so doing, expose ourselves to the charge of inconsistency, – the stupid sneer, the unmeaning laugh, of men to whom experience may preach in vain, may be ours; but we shall have the consolation, the sure reward, of men who, seeking that which will promote the happiness of the family of man, when they find themselves in the wrong course, immediately abandon it for the right.

In the preceding pages we have endeavoured to advocate Free Trade, as the only one thing by which slavery can be destroyed. We now come to a subject of equal importance – the claims of our countrymen at home. We plead not for the Manchester warehouseman, cribbed, cabined, and confined by our wretched system of commercial policy, but we plead for the overtaxed and under-fed hard-working men and women of Great Britain. It is well to be tenderly alive to the concerns of the West Indian negro, but the charity that exhausts itself on them partakes of the same mongrel character as that sensibility which sheds floods of tears over the feigned distresses of the stage, and looks unmoved upon the miseries of a world. A reduction in the price of sugar would most certainly be an inestimable boon to the working man. Such a step taken by government would produce no increase in the consumption of sugar on the part of the middle or higher classes, but it would enable the poorer classes at once to use one of the most nutritious and essential articles of food. If you would preserve a man from drunkenness, make his home happy; let him have something better than the meagre fare which too generally awaits him. On the government which, by its interference, deprives the operative of the fair fruit of his labour, which drives him to the alehouse, to avoid the home rendered wretched by their accursed agency, rest the blame and guilt occasioned by the degradation and destruction of the body and soul of man. Different is the judgment of Heaven from that of the world. Could our voice reach the ears of our senators, we would ask them to pause ere they continued in a course of legislation which has been a fruitful source of vice – a course of legislation which, like the destroying angel, has spread death through the land. We would say to them, “Law-makers, see there the wretched slave of vice; the fault is not his, but yours. From your costly clubs, from your glittering saloons, flushed with revelry and wine, you have gone to the House, and, in the fulness of your power and pride, declared that his hearth should be desolate – that the crust he gnaws he should earn at the price of his life – that misery and want, like attendant handmaids, should follow on his steps; and if he has shrunk abashed from their presence – if his heart has failed him in the hour of need – if he has forgotten his manhood and his immortality – if he has joined in the hideous orgies of the drunken and the desolate – if he has sunk into the condition of the beast – the crime, and shame, and curse, be yours. And you may well shudder with an unwonted fear at the thought of the hour when Heaven shall require an account at your hands – when it shall be asked you why you laid on your brother a burden greater than he could bear, and why you blotted out the image of divinity that was planted there.”

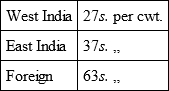

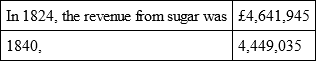

Let us just look at the history of the sugar trade, – we shall soon see how well protection has worked. In 1824, the duty on sugar was —

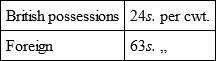

In 1830, the West India duty was reduced to 24s., the East India to 32s., which, as the editor of the Economist has well remarked, was “just so much more put into the pockets of the producers, so long as the 63s. on foreign sugar was continued.” In 1836, a slight change was introduced. The duty on East India was equalised, so that the duty was —

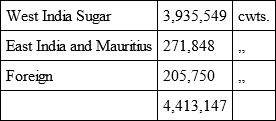

In 1824, we imported —

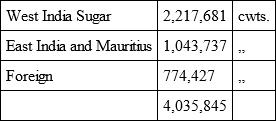

The duty on East India being equalised, and that on foreign remaining as before, we imported in 1840 —

Between 1824 and 1840, the population had increased five millions, and yet there had been an actual falling off in the consumption of sugar of no less than 377,302 cwts. and a loss of revenue of £192,910, to say nothing of the consequent loss of employment which the five millions would otherwise have enjoyed, resulting from the impulse given to manufactures and shipping, by an increase in the sugar trade. The cost, exclusive of duty, of 3,764,710 cwts. retained for home consumption in the year, as calculated by Mr. Porter, at the Gazette average prices, was £9,156,872. The cost of the same quantity of Brazil or Havanna sugar, of equal quality, would have been £4,141,181, so that in one year we paid £5,015,691 more than the prices which the rest of the inhabitants of Europe would have paid for an equal quantity of sugar. In that year the total value of our exports to our sugar colonies was under £4,000,000, so that we should have “gained a million of money in that one year by following the true principle of buying in the cheapest market, even though we had made the sugar-growers a present of all the goods which they took from us.”12

The Brazilian ambassador has been in vain endeavouring to effect a reduction of the duty imposed on foreign sugar. The reign of monopoly is to be continued yet a little longer. We are to go on throwing away our money, and losing our trade. The working man’s food is taxed out of all proportion. We may not use the cheap sugar of Brazil, which is imported – slave-grown as it is – into England, and, here refined, is then sold to the settler in Australia, or the emancipated West Indian labourer, for fourpence a pound. No, the unemancipated white labourer must pay a high price for his adulterated sugar; for be it remembered that 400,000 cwts. of various ingredients are annually used, and which, cheapening the price, though then it is much higher than that of the genuine article would be, were we allowed to import it for home consumption from Brazil, is consumed principally by the lower orders of society. The necessaries of life in this country being thus heavily taxed, the cost of our manufactures is raised, and, as a consequence, the German under-sells us in the Brazil market; and, more wonderful still, the American enters our own colonies, such as the Cape of Good Hope, and under-sells us there; and thus it is that we are punished for our sins. It must also be remembered that, in spite of our virtual exclusion of foreign produce, Java, and Cuba, and the Brazils, had grown sugar in such abundance, as that our merchants have three separate times begged permission of the government to introduce it merely for the purposes of agriculture, promising, if their request were granted, to spoil it in such a manner as that it should be totally unfit for human food.